Forest transition

Forest transition refers to a geographic theory describing a reversal or turnaround in

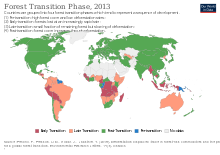

Changes in forest area (like deforestation) may follow a pattern suggested by the forest transition (FT) theory,[9] whereby at early stages in its development a country is characterized by high forest cover and low deforestation rates (HFLD countries).[10]

Then deforestation rates accelerate (HFHD, high forest cover – high deforestation rate), and forest cover is reduced (LFHD, low forest cover – high deforestation rate), before the deforestation rate slows (LFLD, low forest cover – low deforestation rate), after which forest cover stabilizes and eventually starts recovering. FT is not a "law of nature", and the pattern is influenced by national context (for example, human population density, stage of development, structure of the economy), global economic forces, and government policies. A country may reach very low levels of forest cover before it stabilizes, or it might through good policies be able to "bridge" the forest transition.[citation needed]

Theory

FT depicts a broad trend, and an extrapolation of historical rates therefore tends to underestimate future BAU deforestation for countries in the early stages of the transition (HFLD), while it tends to overestimate BAU deforestation for countries in the later stages (LFHD and LFLD).

Countries with high forest cover can be expected to be at early stages of the FT. GDP per capita captures the stage in a country's economic development, which is linked to the pattern of natural resource use, including forests. The choice of forest cover and GDP per capita also fits well with the two key scenarios in the FT:

(i) a forest scarcity path, where forest scarcity triggers forces (for example, higher prices of forest products) that lead to forest cover stabilization; and

(ii) an economic development path, where new and better off-farm employment opportunities associated with economic growth (= increasing GDP per capita) reduce the profitability of frontier agriculture and slows deforestation.[10]

Causes

Forest recovery resulting in net increases in forest extent can occur by means of spontaneous regeneration, active planting, or both.[11][12]

There are two main paths in reforestation, one emerging from economic development and another from forest scarcity.

Demand for forest products, especially wood, resulting from earlier deforestation, also creates market incentives to plant trees and more effectively manage forest resources.[12] Due to forestry intensification, higher forest productivity saves remaining forests from exploitation pressures.[13] Moreover, cultural responses to losses in forest area lead to government intervention to implement policies promoting reforestation.[13]

A Kuznets curve analysis of the problem, where income leads to forest regrowth, has contradictory results, due to the complex interaction of income with many socioeconomic variables (e.g. democratisation, globalisation, etc.)[13] The factors which drive deforestation also control the forest transition, promoting urbanisation, development, changing relative agricultural and urban prices, population density, demand for forest products, land tenure systems, and trade. Transitions involve a combination of socioeconomic feedbacks from forest decline and development.[14]

Global forest transition

Studies of forest transitions have been conducted for several nations as well as sub-national regions.

The environmental effects of these forest transitions are very variable, depending on whether deforestation of old-growth forests continue, the proportions and types of tree plantations versus natural regeneration of forests, and the location and spatial configuration of the different types of forests.[15] In southern Brazil, reforestation mainly occurred through tree plantations, replanting trees, increasing forest cover.[15] And in Honduras, a transition to coffee growing led to abandonment of low-lying regions as coffee farmers moved to high-sloped highland regions.[15]

The findings of returning forests in these widespread studies raise questions about the prospects of a worldwide forest transition, particularly given ongoing processes of

A study on forest transition theory reported that over 60 years (1960–2019), "the global forest area has declined by 81.7 million ha", and concluded higher income nations need to reduce imports of tropical forest-related products and help with theoretically forest-related socioeconomic development and international policies.[34][35]

See also

References

- ^ Mather, Alexander S. (1992). "The forest transition". Area. 24 (4): 367–379.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Walker, R. (1993). "Deforestation and Economic Development". Canadian Journal of Regional Science. 16 (3): 481–497.

- ^ Grainger, Alan (1995). "The forest transition: an alternative approach". Area. 27 (3): 242–251.

- .

- .

- S2CID 140182729.

- ^ Meyfroidt & Lambin 2011, p. 344.

- ^ a b Walker, R. (2011). "The scale of forest transition: Amazonia and the Atlantic forests of Brazil". Applied Geography. 32 (1): 12–20.

- ^ Meyfroidt & Lambin 2011.

- ^ ISBN 0-231-13195-X

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d e Meyfroidt & Lambin 2011, p. 348.

- ^ a b c d Meyfroidt & Lambin 2011, p. 349.

- ^ Meyfroidt & Lambin 2011, p. 353.

- ^ a b c d Meyfroidt & Lambin 2011, p. 350.

- .

- ^ S2CID 131549198.

- .

- .

- S2CID 128468075.

- S2CID 43455468.

- S2CID 129628209.

- .

- S2CID 86436706.

- ^ Meyfroidt, Patrick; Lambin, Eric F. (2007). "The causes of the reforestation in Vietnam". Land Use Policy. 25 (2): 182–197.

- S2CID 154476196.

- S2CID 86716728.

- S2CID 53055910.

- S2CID 59370821.

- .

- PMID 17101996.

- ^ Meyfroidt & Lambin 2011, p. 356.

- ^ a b Meyfroidt & Lambin 2011, p. 357.

- ^ "200 million acres of forest cover have been lost since 1960". Grist. 5 August 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ISSN 1748-9326.

Bibliography

- Meyfroidt, Patrick;