Fortified wine

Fortified wine is a

Production

One reason for fortifying wine was to preserve it, since ethanol is also a natural antiseptic. Even though other preservation methods now exist, fortification continues to be used because the process can add distinct flavors to the finished product.[4][5]

Although grape brandy is most commonly added to produce fortified wines, the additional alcohol may also be

The source of the additional alcohol and the method of its distillation can affect the flavour of the fortified wine. If

When added to wine before the

During the fermentation process, yeast cells in the must continue to convert sugar into alcohol until the must reaches an alcohol level of 16–18%. At this level, the alcohol becomes toxic to the yeast and stalls its metabolism. If fermentation is allowed to run to completion, the resulting wine is (in most cases) low in sugar and is considered a dry wine. Adding alcohol earlier in the fermentation process results in a sweeter wine. For drier fortified wine styles, such as sherry, the alcohol is added shortly before or after the end of the fermentation.

In the case of some fortified wine styles (such as late harvest and botrytized wines), a naturally high level of sugar inhibits the yeast, or the rising alcohol content due to the high sugar kills the yeast. This causes fermentation to stop before the wine can become dry.[3]

Varieties

Commandaria wine

Commandaria is made in Cyprus' unique AOC region north of Limassol from high-altitude vines of Mavro and Xynisteri, sun-dried and aged in oak barrels. Recent developments have produced different styles of Commandaria, some of which are not fortified.

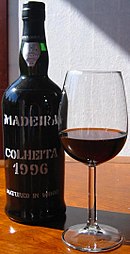

Madeira wine

Madeira is a fortified wine made in the

Marsala wine

Marsala wine is a wine from

Mistelle

Mistelle (

Moscatel de Setúbal

Moscatel de Setúbal is a Portuguese wine produced around the

Port wine

Port wine (also known simply as port) is a fortified wine from the

Sherry

Sherry is a fortified wine made from white grapes that are grown near the town of

After

Sherry is produced in a variety of styles, ranging from dry, light versions such as finos to much darker and sometimes sweeter versions known as olorosos.[14] Cream sherry is always sweet.

Vermouth

Vermouth is a fortified wine flavoured with aromatic herbs and spices ("aromatised" in the trade) using closely guarded recipes (trade secrets). Some of the herbs and spices used may include cardamom, cinnamon, marjoram, and chamomile.[15] Some vermouth is sweetened. Unsweetened or dry vermouth tends to be bitter. The person credited with the second vermouth recipe, Antonio Benedetto Carpano from Turin, Italy, chose to name his concoction "vermouth" in 1786 because he was inspired by a German wine flavoured with wormwood, an herb most famously used in distilling absinthe. Wine flavoured with wormwood goes back to ancient Rome. The modern German word Wermut (Wermuth in the spelling of Carpano's time) means both wormwood and vermouth. The herbs were originally used to mask raw flavours of cheaper wines,[16] imparting a slightly medicinal "tonic" flavor.

Vins doux naturels

Vins doux naturels (VDN) are lightly fortified wines typically made from white

As the name suggests,

Vins de liqueur

A vin de liqueur is a sweet fortified style of French wine that is fortified by adding brandy to unfermented grape must. The term vin de liqueur is also used by the European Union to refer to all fortified wines. Vins de liqueur take greater flavour from the added brandy but are also sweeter than vin doux.

Examples include

similarly made by blending apple juice and apple brandy.Low-end fortified wines

Inexpensive fortified wines, such as Thunderbird and Wild Irish Rose, became popular during the Great Depression for their relatively high alcohol content. The term wino was coined during this period to describe impoverished alcoholics of the time.[19]

These wines continue to be associated with the homeless, mainly because marketers have been aggressive in targeting low-income communities as ideal consumers of these beverages; organisations in cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland have urged makers of inexpensive fortified wine, including

Gwaha-ju

Gwaha-ju is a fortified rice wine made in Korea.[23][24] Although rice wine is not made from grapes, it has a similar alcohol content to grape wine, and the addition of the distilled spirit, soju, and other ingredients like ginseng, jujubes, ginger, etc., to the rice wine, bears similarity to the above-mentioned fortified wines.

Terminology

Fortified wines are often termed

Under

See also

- Wine and health

References

- ISBN 0-394-56262-3.

- ISBN 9780760758328. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

Exactly when stronger wines or spirits began to be added to wine to preserve it is lost to history, but it worked — and fortified wine was born. History does record how the fortified wines Port and Madeira came to be.

- ^ ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- ^ "Types of Fortified Wines You Might Enjoy Before or After Dinner". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ Antonello, Biancalana. "DiWineTaste Report: Tasting Fortified Wines". DiWineTaste. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ "26 U.S. Code §5382 b(2)". Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84022-302-6. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-57806-841-8. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

Marsala wine.

- OCLC 41660699.

- ^ "mistelle Definition in the Wine Dictionary at Epicurious.com". epicurious.com. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ Biancalana, Antonello. "Production of Fortified Wines". DiWineTaste. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ISBN 0-02-863601-5.

- ^ "Spanish law". Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ^ "Sherry types". SherryNotes. 23 July 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ^ Clarke, Paul (15 August 2008). "The Truth About Vermouth: The secret ingredient in today's top cocktails remains misunderstood". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ISBN 978-0-470-10752-2. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-8476-7534-0. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ "thewinedoctor.com". Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ISBN 1-4027-2585-X.

- ISBN 1-55862-336-1.

- ^ Castro, Hector (7 December 2005). "City could soon widen alcohol impact areas". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. [dead link]

- ^ "Public Safety - Alcohol Impact Areas". Beacon Alliance of Neighbors. City of Seattle. 1 January 2013. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Yu, Tae-jong. "Gwaha-ju". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ Park, Rock Darm (12 April 2012). "Gwaha-ju". Naver (in Korean). Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-520-92087-3. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-904777-85-4. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- ^ "Council Regulation (EC) No 479/2008; Annex IV, §3 (European Union document". p. 46.

External links

- Commandaria wine and its evolution.

- Dessert Wines (fortified wine production).

- Fortification calculator

- Fortified Wines