FOSB

Ensembl | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt | |||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | |||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | |||||||||

| Location (UCSC) | Chr 19: 45.47 – 45.48 Mb | Chr 7: 19.04 – 19.04 Mb | |||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

Protein fosB, also known as FosB and G0/G1 switch regulatory protein 3 (G0S3), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (FOSB) gene.[5][6][7]

The FOS gene family consists of four members:

The ΔFosB

DeltaFosB

DeltaFosB – more commonly written as ΔFosB – is a truncated

In the

Chronic administration of anandamide, or N-arachidonylethanolamide (AEA), an endogenous cannabinoid, and additives such as sucralose, a noncaloric sweetener used in many food products of daily intake, are found to induce an overexpression of ΔFosB in the infralimbic cortex (Cx), nucleus accumbens (NAc) core, shell, and central nucleus of amygdala (Amy), that induce long-term changes in the reward system.[23]

Role in addiction

| Addiction and dependence glossary[12][24][25] | |

|---|---|

| |

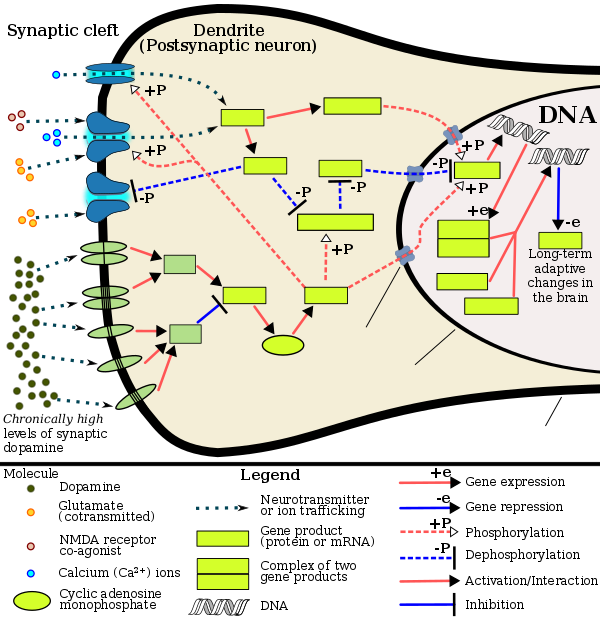

Signaling cascade in the nucleus accumbens that results in psychostimulant addiction |

Chronic

ΔFosB also plays an important role in regulating behavioral responses to

ΔFosB inhibitors (drugs or treatments that oppose its action or reduce its expression) may be an effective treatment for addiction and addictive disorders.

Plasticity in cocaine addiction

ΔFosB levels have been found to increase upon the use of cocaine.

Transgenic mice exhibiting inducible expression of ΔFosB primarily in the nucleus accumbens and

| Target gene |

Target expression |

Neural effects | Behavioral effects |

|---|---|---|---|

c-Fos |

↓ | Molecular switch enabling the chronic induction of ΔFosB[note 5] |

– |

| dynorphin | ↓ [note 6] |

• Downregulation of κ-opioid feedback loop | • Diminished self-extinguishing response to drug |

| NF-κB | ↑ | • Expansion of CP |

• Increased drug reward • Locomotor sensitization |

GluR2 |

↑ | • Decreased glutamate |

• Increased drug reward |

Cdk5 |

↑ | • GluR1 synaptic protein phosphorylation • Expansion of NAcc dendritic processes |

• Decreased drug reward (net effect) |

| Form of neuroplasticity or behavioral plasticity |

Type of reinforcer | Sources | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opiates | Psychostimulants | High fat or sugar food | Sexual intercourse | Physical exercise (aerobic) |

Environmental enrichment | ||

| ΔFosB expression in MSNs

|

↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [11] |

| Behavioral plasticity | |||||||

| Escalation of intake | Yes | Yes | Yes | [11] | |||

| Psychostimulant cross-sensitization |

Yes | Not applicable | Yes | Yes | Attenuated | Attenuated | [11] |

| Psychostimulant self-administration |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [11] | |

| Psychostimulant conditioned place preference |

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | [11] |

Reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior

|

↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | [11] | ||

| Neurochemical plasticity | |||||||

CREB phosphorylation in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [11] | |

| Sensitized dopamine response in the nucleus accumbens |

No | Yes | No | Yes | [11] | ||

| Altered striatal dopamine signaling | ↓ DRD3 |

↑ DRD3 |

↑ DRD3 |

↑ DRD2 |

↑ DRD2 |

[11] | |

| Altered striatal opioid signaling | No change or ↑μ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors ↑κ-opioid receptors |

↑μ-opioid receptors | ↑μ-opioid receptors | No change | No change | [11] |

| Changes in striatal opioid peptides | ↑dynorphin No change: enkephalin |

↑dynorphin | ↓enkephalin | ↑dynorphin | ↑dynorphin | [11] | |

| Mesocorticolimbic synaptic plasticity | |||||||

| Number of dendrites in the nucleus accumbens | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [11] | |||

| Dendritic spine density in the nucleus accumbens |

↓ | ↑ | ↑ | [11] | |||

Other functions in the brain

Viral overexpression of ΔFosB in the output neurons of the

ΔFosB expression in the

See also

- AP-1 (transcription factor)

Notes

- reward sensitization, this effect occurs with the other as well.

- medical indicationsunrelated to addiction.

- motivational anhedonia) and reduce the amount of the drug that is self-administered when it is readily available.[36][40][41]

- ^ Among the few clinical trials that employed a class I HDAC inhibitor, one utilized valproate for methamphetamine addiction.[43]

- ^ In other words, c-Fos repression allows ΔFosB to accumulate within nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons more rapidly because it is selectively induced in this state.[12]

- ^ ΔFosB has been implicated in causing both increases and decreases in dynorphin expression in different studies;[9][17] this table entry reflects only a decrease.

- Image legend

- G proteins & linked receptors(Text color) Transcription factors

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000125740 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000003545 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: FOSB FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B".

- PMID 1702972.

- S2CID 1986255.

- PMID 18433296.

- ^ S2CID 19157711.

ΔFosB as a therapeutic biomarker

The strong correlation between chronic drug exposure and ΔFosB provides novel opportunities for targeted therapies in addiction (118), and suggests methods to analyze their efficacy (119). Over the past two decades, research has progressed from identifying ΔFosB induction to investigating its subsequent action (38). It is likely that ΔFosB research will now progress into a new era – the use of ΔFosB as a biomarker. If ΔFosB detection is indicative of chronic drug exposure (and is at least partly responsible for dependence of the substance), then its monitoring for therapeutic efficacy in interventional studies is a suitable biomarker (Figure 2). Examples of therapeutic avenues are discussed herein. ...

Conclusions

ΔFosB is an essential transcription factor implicated in the molecular and behavioral pathways of addiction following repeated drug exposure. The formation of ΔFosB in multiple brain regions, and the molecular pathway leading to the formation of AP-1 complexes is well understood. The establishment of a functional purpose for ΔFosB has allowed further determination as to some of the key aspects of its molecular cascades, involving effectors such as GluR2 (87,88), Cdk5 (93) and NFkB (100). Moreover, many of these molecular changes identified are now directly linked to the structural, physiological and behavioral changes observed following chronic drug exposure (60,95,97,102). New frontiers of research investigating the molecular roles of ΔFosB have been opened by epigenetic studies, and recent advances have illustrated the role of ΔFosB acting on DNA and histones, truly as a molecular switch (34). As a consequence of our improved understanding of ΔFosB in addiction, it is possible to evaluate the addictive potential of current medications (119), as well as use it as a biomarker for assessing the efficacy of therapeutic interventions (121,122,124). Some of these proposed interventions have limitations (125) or are in their infancy (75). However, it is hoped that some of these preliminary findings may lead to innovative treatments, which are much needed in addiction. - ^ PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB has been linked directly to several addiction-related behaviors ... Importantly, genetic or viral overexpression of ΔJunD, a dominant negative mutant of JunD which antagonizes ΔFosB- and other AP-1-mediated transcriptional activity, in the NAc or OFC blocks these key effects of drug exposure14,22–24. This indicates that ΔFosB is both necessary and sufficient for many of the changes wrought in the brain by chronic drug exposure. ΔFosB is also induced in D1-type NAc MSNs by chronic consumption of several natural rewards, including sucrose, high fat food, sex, wheel running, where it promotes that consumption14,26–30. This implicates ΔFosB in the regulation of natural rewards under normal conditions and perhaps during pathological addictive-like states.

- ^ PMID 21459101.

Cross-sensitization is also bidirectional, as a history of amphetamine administration facilitates sexual behavior and enhances the associated increase in NAc DA ... As described for food reward, sexual experience can also lead to activation of plasticity-related signaling cascades. The transcription factor delta FosB is increased in the NAc, PFC, dorsal striatum, and VTA following repeated sexual behavior (Wallace et al., 2008; Pitchers et al., 2010b). This natural increase in delta FosB or viral overexpression of delta FosB within the NAc modulates sexual performance, and NAc blockade of delta FosB attenuates this behavior (Hedges et al, 2009; Pitchers et al., 2010b). Further, viral overexpression of delta FosB enhances the conditioned place preference for an environment paired with sexual experience (Hedges et al., 2009). ... In some people, there is a transition from "normal" to compulsive engagement in natural rewards (such as food or sex), a condition that some have termed behavioral or non-drug addictions (Holden, 2001; Grant et al., 2006a). ... In humans, the role of dopamine signaling in incentive-sensitization processes has recently been highlighted by the observation of a dopamine dysregulation syndrome in some patients taking dopaminergic drugs. This syndrome is characterized by a medication-induced increase in (or compulsive) engagement in non-drug rewards such as gambling, shopping, or sex (Evans et al, 2006; Aiken, 2007; Lader, 2008).

Table 1 - ^ PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type [nucleus accumbens] neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41 ... Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.

- ^ PMID 23020045.

For these reasons, ΔFosB is considered a primary and causative transcription factor in creating new neural connections in the reward centre, prefrontal cortex, and other regions of the limbic system. This is reflected in the increased, stable and long-lasting level of sensitivity to cocaine and other drugs, and tendency to relapse even after long periods of abstinence. These newly constructed networks function very efficiently via new pathways as soon as drugs of abuse are further taken ... In this way, the induction of CDK5 gene expression occurs together with suppression of the G9A gene coding for dimethyltransferase acting on the histone H3. A feedback mechanism can be observed in the regulation of these 2 crucial factors that determine the adaptive epigenetic response to cocaine. This depends on ΔFosB inhibiting G9a gene expression, i.e. H3K9me2 synthesis which in turn inhibits transcription factors for ΔFosB. For this reason, the observed hyper-expression of G9a, which ensures high levels of the dimethylated form of histone H3, eliminates the neuronal structural and plasticity effects caused by cocaine by means of this feedback which blocks ΔFosB transcription

- PMID 25313003.

- S2CID 23904956.

- ^ PMID 22641964.

- ^ PMID 18640924.

Recent evidence has shown that ΔFosB also represses the c-fos gene that helps create the molecular switch—from the induction of several short-lived Fos family proteins after acute drug exposure to the predominant accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic drug exposure—cited earlier (Renthal et al. in press). The mechanism responsible for ΔFosB repression of c-fos expression is complex and is covered below. ...

Examples of validated targets for ΔFosB in nucleus accumbens ... GluR2 ... dynorphin ... Cdk5 ... NFκB ... c-Fos

Table 3 - PMID 18635399.

- PMID 19447090.

- S2CID 20302360.

- ^ PMID 21989194.

ΔFosB serves as one of the master control proteins governing this structural plasticity. ... ΔFosB also represses G9a expression, leading to reduced repressive histone methylation at the cdk5 gene. The net result is gene activation and increased CDK5 expression. ... In contrast, ΔFosB binds to the c-fos gene and recruits several co-repressors, including HDAC1 (histone deacetylase 1) and SIRT 1 (sirtuin 1). ... The net result is c-fos gene repression.

Figure 4: Epigenetic basis of drug regulation of gene expression - ^ PMID 11572966.

- S2CID 210149592.

- ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

- PMID 26816013.

Substance-use disorder: A diagnostic term in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) referring to recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Depending on the level of severity, this disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. - ^ PMID 19877494.

[Psychostimulants] increase cAMP levels in striatum, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and leads to phosphorylation of its targets. This includes the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), the phosphorylation of which induces its association with the histone acetyltransferase, CREB binding protein (CBP) to acetylate histones and facilitate gene activation. This is known to occur on many genes including fosB and c-fos in response to psychostimulant exposure. ΔFosB is also upregulated by chronic psychostimulant treatments, and is known to activate certain genes (eg, cdk5) and repress others (eg, c-fos) where it recruits HDAC1 as a corepressor. ... Chronic exposure to psychostimulants increases glutamatergic [signaling] from the prefrontal cortex to the NAc. Glutamatergic signaling elevates Ca2+ levels in NAc postsynaptic elements where it activates CaMK (calcium/calmodulin protein kinases) signaling, which, in addition to phosphorylating CREB, also phosphorylates HDAC5.

Figure 2: Psychostimulant-induced signaling events - PMID 22200950.

Coincident and convergent input often induces plasticity on a postsynaptic neuron. The NAc integrates processed information about the environment from basolateral amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex (PFC), as well as projections from midbrain dopamine neurons. Previous studies have demonstrated how dopamine modulates this integrative process. For example, high frequency stimulation potentiates hippocampal inputs to the NAc while simultaneously depressing PFC synapses (Goto and Grace, 2005). The converse was also shown to be true; stimulation at PFC potentiates PFC–NAc synapses but depresses hippocampal–NAc synapses. In light of the new functional evidence of midbrain dopamine/glutamate co-transmission (references above), new experiments of NAc function will have to test whether midbrain glutamatergic inputs bias or filter either limbic or cortical inputs to guide goal-directed behavior.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (10 October 2014). "Amphetamine – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

Most addictive drugs increase extracellular concentrations of dopamine (DA) in nucleus accumbens (NAc) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), projection areas of mesocorticolimbic DA neurons and key components of the "brain reward circuit". Amphetamine achieves this elevation in extracellular levels of DA by promoting efflux from synaptic terminals. ... Chronic exposure to amphetamine induces a unique transcription factor delta FosB, which plays an essential role in long-term adaptive changes in the brain.

- PMID 24939695.

- ^ PMID 23430970.

The 35-37 kD ΔFosB isoforms accumulate with chronic drug exposure due to their extraordinarily long half-lives. ... As a result of its stability, the ΔFosB protein persists in neurons for at least several weeks after cessation of drug exposure. ... ΔFosB overexpression in nucleus accumbens induces NFκB ... In contrast, the ability of ΔFosB to repress the c-Fos gene occurs in concert with the recruitment of a histone deacetylase and presumably several other repressive proteins such as a repressive histone methyltransferase

- PMID 18640924.

Recent evidence has shown that ΔFosB also represses the c-fos gene that helps create the molecular switch—from the induction of several short-lived Fos family proteins after acute drug exposure to the predominant accumulation of ΔFosB after chronic drug exposure

- ^ PMID 16776597.

- PMID 23085425.

- ^ Kanehisa Laboratories (29 October 2014). "Alcoholism – Homo sapiens (human)". KEGG Pathway. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- PMID 19202072.

- ^ PMID 23643695.

Short-term increases in histone acetylation generally promote behavioral responses to the drugs, while sustained increases oppose cocaine's effects, based on the actions of systemic or intra-NAc administration of HDAC inhibitors. ... Genetic or pharmacological blockade of G9a in the NAc potentiates behavioral responses to cocaine and opiates, whereas increasing G9a function exerts the opposite effect (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). Such drug-induced downregulation of G9a and H3K9me2 also sensitizes animals to the deleterious effects of subsequent chronic stress (Covington et al., 2011). Downregulation of G9a increases the dendritic arborization of NAc neurons, and is associated with increased expression of numerous proteins implicated in synaptic function, which directly connects altered G9a/H3K9me2 in the synaptic plasticity associated with addiction (Maze et al., 2010).

G9a appears to be a critical control point for epigenetic regulation in NAc, as we know it functions in two negative feedback loops. It opposes the induction of ΔFosB, a long-lasting transcription factor important for drug addiction (Robison and Nestler, 2011), while ΔFosB in turn suppresses G9a expression (Maze et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2012a). ... Also, G9a is induced in NAc upon prolonged HDAC inhibition, which explains the paradoxical attenuation of cocaine's behavioral effects seen under these conditions, as noted above (Kennedy et al., 2013). GABAA receptor subunit genes are among those that are controlled by this feedback loop. Thus, chronic cocaine, or prolonged HDAC inhibition, induces several GABAA receptor subunits in NAc, which is associated with increased frequency of inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSCs). In striking contrast, combined exposure to cocaine and HDAC inhibition, which triggers the induction of G9a and increased global levels of H3K9me2, leads to blockade of GABAA receptor and IPSC regulation. - PMID 23426671.

- ISBN 9780071481274.

- ^ PMID 27453897.

Epigenetic modifications caused by addictive drugs play an important role in neuronal plasticity and in drug-induced behavioral responses. Although few studies have investigated the effects of AMPH on gene regulation (Table 1), current data suggest that AMPH acts at multiple levels to alter histone/DNA interaction and to recruit transcription factors which ultimately cause repression of some genes and activation of other genes. Importantly, some studies have also correlated the epigenetic regulation induced by AMPH with the behavioral outcomes caused by this drug, suggesting therefore that epigenetics remodeling underlies the behavioral changes induced by AMPH. If this proves to be true, the use of specific drugs that inhibit histone acetylation, methylation or DNA methylation might be an important therapeutic alternative to prevent and/or reverse AMPH addiction and mitigate the side effects generate by AMPH when used to treat ADHD.

- ^ PMID 25486626.

Studies investigating general HDAC inhibition on behavioral outcomes have produced varying results but it seems that the effects are specific to the timing of exposure (either before, during or after exposure to drugs of abuse) as well as the length of exposure

- ^ PMID 25880762.

treatment with NaB significantly attenuated nicotine and nicotine + cue reinstatement when administered immediately ... These results provide the first demonstration that HDAC inhibition facilitates the extinction of responding for an intravenously self-administered drug of abuse and further highlight the potential of HDAC inhibitors in the treatment of drug addiction.

- PMID 25623036.

Increased HDAC2 expression decreases the expression of genes important for the maintenance of dendritic spine density such as BDNF, Arc, and NPY, leading to increased anxiety and alcohol-seeking behavior. Decreasing HDAC2 reverses both the molecular and behavioral consequences of alcohol addiction, thus implicating this enzyme as a potential treatment target (Fig. 3). HDAC2 is also crucial for the induction and maintenance of structural synaptic plasticity in other neurological domains such as memory formation [115]. Taken together, these findings underscore the potential usefulness of HDAC inhibition in treating alcohol use disorders ... Given the ability of HDAC inhibitors to potently modulate the synaptic plasticity of learning and memory [118], these drugs hold potential as treatment for substance abuse-related disorders. ... Our lab and others have published extensively on the ability of HDAC inhibitors to reverse the gene expression deficits caused by multiple models of alcoholism and alcohol abuse, the results of which were discussed above [25,112,113]. This data supports further examination of histone modifying agents as potential therapeutic drugs in the treatment of alcohol addiction ... Future studies should continue to elucidate the specific epigenetic mechanisms underlying compulsive alcohol use and alcoholism, as this is likely to provide new molecular targets for clinical intervention.

- PMID 27656618.

- S2CID 11683570.

- ^ S2CID 4390717.

- ^ PMID 12657709.

- PMID 20505100.

- ^ PMID 25692070.

Furthermore, the transgenic overexpression of ΔFosB reproduces AIMs in hemiparkinsonian rats without chronic exposure to L-DOPA [13]. ... FosB/ΔFosB immunoreactive neurons increased in the dorsolateral part of the striatum on the lesion side with the used antibody that recognizes all members of the FosB family. All doses of levetiracetam decreased the number of FosB/ΔFosB positive cells (from 88.7 ± 1.7/section in the control group to 65.7 ± 0.87, 42.3 ± 1.88, and 25.7 ± 1.2/section in the 15, 30, and 60 mg groups, resp.; Figure 2). These results indicate dose-dependent effects of levetiracetam on FosB/ΔFosB expression. ... In addition, transcription factors expressed with chronic events such as ΔFosB (a truncated splice variant of FosB) are overexpressed in the striatum of rodents and primates with dyskinesias [9, 10]. ... Furthermore, ΔFosB overexpression has been observed in postmortem striatal studies of Parkinsonian patients chronically treated with L-DOPA [26]. ... Of note, the most prominent effect of levetiracetam was the reduction of ΔFosB expression, which cannot be explained by any of its known actions on vesicular protein or ion channels. Therefore, the exact mechanism(s) underlying the antiepileptic effects of levetiracetam remains uncertain.

- ^ "ROLE OF ΔFOSB IN THE NUCLEUS ACCUMBENS". Mount Sinai School of Medicine. NESTLER LAB: LABORATORY OF MOLECULAR PSYCHIATRY. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- PMID 22868883.

- PMID 25446562.

In more recent years, prolonged induction of ∆FosB has also been observed within NAc in response to chronic administration of certain forms of stress. Increasing evidence indicates that this induction represents a positive, homeostatic adaptation to chronic stress, since overexpression of ∆FosB in this brain region promotes resilience to stress, whereas blockade of its activity promotes stress susceptibility. Chronic administration of several antidepressant medications also induces ∆FosB in the NAc, and this induction is required for the therapeutic-like actions of these drugs in mouse models. Validation of these rodent findings is the demonstration that depressed humans, examined at autopsy, display reduced levels of ∆FosB within the NAc. As a transcription factor, ΔFosB produces this behavioral phenotype by regulating the expression of specific target genes, which are under current investigation. These studies of ΔFosB are providing new insight into the molecular basis of depression and antidepressant action, which is defining a host of new targets for possible therapeutic development.

- PMID 24067299.

Further reading

- Schuermann M, Jooss K, Müller R (April 1991). "fosB is a transforming gene encoding a transcriptional activator". Oncogene. 6 (4): 567–76. PMID 1903195.

- Brown JR, Ye H, Bronson RT, Dikkes P, Greenberg ME (July 1996). "A defect in nurturing in mice lacking the immediate early gene fosB". Cell. 86 (2): 297–309. S2CID 17266171.

- Heximer SP, Cristillo AD, Russell L, Forsdyke DR (December 1996). "Sequence analysis and expression in cultured lymphocytes of the human FOSB gene (G0S3)". DNA and Cell Biology. 15 (12): 1025–38. PMID 8985116.

- Liberati NT, Datto MB, Frederick JP, Shen X, Wong C, Rougier-Chapman EM, Wang XF (April 1999). "Smads bind directly to the Jun family of AP-1 transcription factors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (9): 4844–9. PMID 10220381.

- Yamamura Y, Hua X, Bergelson S, Lodish HF (November 2000). "Critical role of Smads and AP-1 complex in transforming growth factor-beta -dependent apoptosis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (46): 36295–302. PMID 10942775.

- Bergman MR, Cheng S, Honbo N, Piacentini L, Karliner JS, Lovett DH (February 2003). "A functional activating protein 1 (AP-1) site regulates matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP-2) transcription by cardiac cells through interactions with JunB-Fra1 and JunB-FosB heterodimers". PMID 12371906.

- Milde-Langosch K, Kappes H, Riethdorf S, Löning T, Bamberger AM (February 2003). "FosB is highly expressed in normal mammary epithelia, but down-regulated in poorly differentiated breast carcinomas". Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 77 (3): 265–75. S2CID 987857.

- Baumann S, Hess J, Eichhorst ST, Krueger A, Angel P, Krammer PH, Kirchhoff S (March 2003). "An unexpected role for FosB in activation-induced cell death of T cells". Oncogene. 22 (9): 1333–9. S2CID 10696422.

- Holmes DI, Zachary I (January 2004). "Placental growth factor induces FosB and c-Fos gene expression via Flt-1 receptors". FEBS Letters. 557 (1–3): 93–8. S2CID 6596900.

- Konsman JP, Blomqvist A (May 2005). "Forebrain patterns of c-Fos and FosB induction during cancer-associated anorexia-cachexia in rat". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (10): 2752–66. S2CID 40045788.

External links

- ROLE OF ΔFOSB IN THE NUCLEUS ACCUMBENS Archived 28 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- KEGG Pathway – human alcohol addiction

- KEGG Pathway – human amphetamine addiction

- KEGG Pathway – human cocaine addiction

- FOSB+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.