France–Asia relations

France–Asia relations span a period of more than two millennia, starting in the 6th century

Antiquity

The Phoenicians had an early presence around Marseille in southern France. Phoenician inscriptions have been found there.[1]

The oldest city of France, Marseille, was formally founded in 600 BCE by Greeks from the

The mother city of Phocaea would ultimately be destroyed by the Persians in 545 BCE, further reinforcing the exodus of the Phocaeans to their settlements of the Western Mediterranean.[3][5] Populations intermixed, becoming half-Greek and half-indigenous.[3] Trading links were extensive, in iron, spices, wheat and slaves, and with tin being imported to Marseille overland from Cornwall.[3] The Greek settlements permitted cultural interaction between the Greeks and the Celts, and in particular helped develop an urban way of life in Celtic lands, contacts with sophisticated Greek methods, as well as regular East-West trade.[6]

Overland trade with Celtic countries declined around 500 however, with the troubles following the end of the Halstatt civilization.[3]

Because of demographic pressure, the

A part of the invasion crossed over to

In 189 BCE Rome sent Gnaeus Manlius Vulso on an expedition against the Galatians. He defeated them. Galatia was henceforth dominated by Rome through regional rulers from 189 BCE onward.[10]

Christianity, following its emergence in the

The first written records of Christians in France date from the 2nd century when Irenaeus detailed the deaths of ninety-year-old bishop Pothinus of Lugdunum (Lyon) and other martyrs of the 177 persecution in Lyon.[13]

In 496

In the beginning of the 5th century, various Asian nomadic tribes of

From 414,

The Roman general

.

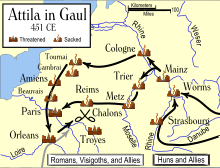

In 450

The Romans under

Middle Ages

Exchanges with the Arab world (8th–13th centuries)

Following the rise of

Various exchanges are known around that time, as when Arculf, a Frankish Bishop, visited the Holy Land in the 670s.[22][23]

Abbasid-Carolingian alliance

An

These contacts followed an intense conflict between the Carolingians and the

Cultural and scientific exchanges

From the 10th to the 13th century,

France and the Near East (16th–19th centuries)

Between the 16th and 19th century, France had at times a relatively dormant relation with the

Franco-Ottoman alliance (16th–18th centuries)

Under the reign of Francis I, France became the first country in Europe to establish formal relations with the

A

The French forces, led by

The strategic and sometimes tactical alliance lasted for about three centuries,

French diplomacy with Persia (16th–19th centuries)

The advent of Shah

When the tide turned in 1604 as Persia gained the upper hand against Ottonan Turkey, the French ambassador to the Porte,

French endeavors in the Near East remained cautious and limited even after the fall of the

Franco-Persian alliance (19th century)

Despite the hostility of Russian Empress

Following his victory at

The treaty included French support for Persia to reclaim its lost territories comprising Georgia and other territories in the Caucasus that were occupied by Russia by that time, promising to act so that Russia would surrender the territory. In exchange, Persia was to fight Great Britain, and allow France to cross the Persian territory to eventually reach India.[41]

Changes in the political atmosphere that marked the peace between France and Russia at the

French plans in Egypt

Napoleon attempted to establish a decisive French presence in Asia, by first launching his

Commercial, religious and military expansion (16th–18th century)

Early-modern contacts with East-Asia (1527-)

France began trading with Eastern Asia from the early 16th century. In 1526, a sailor from Honfleur named Pierre Caunay sailed to Sumatra. He lost his ship on the return leg between Africa and Madagascar, where the crew was imprisoned by the Portuguese.[46] In July 1527, a French Norman trading ship from Rouen is recorded by the Portuguese João de Barros to have arrived in the Indian city of Diu.[47] The next year, a ship under Jean de Breuilly also arrived in Diu, but this time was seized by the Portuguese.[46]

In 1529, Jean Parmentier, sailing with the Sacre and the Pensée, reached Sumatra.[47][48] Upon its return, the expedition triggered the development of the Dieppe maps, influencing the work of Dieppe cartographers, such as Jean Rotz.[49]

Following the Portuguese and Spanish forays into Asia after 1500, a few Frenchmen participated in the activities of Catholic religious orders in these countries during the 16th century. The first instance of

François Pyrard and François Martin (1601–1611)

In December 1600 a company was formed through the association of

From 1604 to 1609, following the return of François Martin de Vitré,

On the missionary front,

Hasekura Tsunenaga (1615)

Company of the Moluccas (1615)

In 1615, the regent

In 1619, an armed expedition composed of three ships (275 crew, 106 cannons) called the "Fleet of Montmorency" under General

As regards Asia and the East Indies there is no hope of planting colonies, for the way is too long, and the Spaniards and Dutch are too strong to suffer it.

— Isaac de Razilly, 1625.[47]

However, trade further developed, with the activities of people such as Jean de Thévenot and Jean-Baptiste Tavernier in 17th century Asia. Gilles de Régimont travelled to Persia and India in 1630 and returned in 1632 with a rich cargo. He formed a trading company at Dieppe in 1633, and sent ships every year to the Indian Ocean.[51][55]

In 1638, the Honfleur sailor

Expansion under Louis XIV

France adopted a more structured approach to its expansion in Asia during the 17th century during the rule of Louis XIV, in an organized attempt to establish a mercantile empire by taking a share of the lucrative market of the Indian Ocean.[57] On the religious plane, the Paris Foreign Missions Society was formed from 1658 in order to provide for missionary work in Asia mainly, under French control. Soon after, the French East India Company was established in 1664.

In 1664 a mission was sent to

In 1672, Caron helped lead French forces in

During the reign of Louis XIV, France further developed

Louis XV/ Louis XVI

After these first experiences, France took a more active role in Asia from its base in India. France was able to establish the beginnings of a commercial and territorial empire in India, leading to the formation of

The geographical exploration of Asia was expanded thanks to the efforts of

Following the development of

France thus managed to gain strong positions in

Trade also developed, with the activities of people such as Pierre Poivre who dealt with Vietnam from the 1720s.

Asia in 17th–18th-century French art

The discovery of Asia led to a strong cultural interest in Asian arts. France especially developed a taste for artistic forms derived from Chinese art and narratives, called Chinoiserie, as well as for Turkish scenes, called Turquerie. French textile industry was also strongly influenced by Asian style, with the development of the silk and tapestry industries. A carpet industry façon de Turquie ("in the manner of Turkey") was developed in France in the reign of Henry IV by Pierre Dupont, who was returning from the Levant, and especially rose to prominence during the reign of Louis XIV.[66] The Tapis de Savonnerie especially exemplify this tradition ("the superb carpets of the Savonnerie, which long rivalled the carpets of Turkey, and latterly have far surpassed them")[67] which was further adapted to local taste and developed with the Gobelins carpets. This tradition also spread to Great Britain where it revived the British carpet industry in the 18th century.[68]

Napoleon's Asian ventures

For a brief period (1806—1815), France had an intense role in

After the Napoleonic era, some former soldiers of Napoleon left France as mercenaries in Asian countries. One of them

Colonial era

Through its defeat in the Napoleonic wars, France lost most of its colonial possessions, but the 19th century brought an era of

French Indochina

In the 1820s, France tried to reestablish contacts with

Northern Vietnam was then disputed with China, leading to the

China campaigns

France intervened several times in China, together with other Western powers, to expand Western influence there. France participated actively to the Second Opium War in 1860, also using religious persecutions as a pretext. In 1900, the Boxer Rebellion led to massive French and Western intervention.

Korea

France also had an interventionist role in northeastern Asia throughout the second half of the 19th century.

In Korea, religious persecutions again motivated the

Japan

In Japan, France had a key role in fighting anti-foreign forces and supporting the

Although the shōgun was defeated in the Boshin war, France continued to take an active role in supporting Japan military through the

Asia in 19th-century French art

Asia influenced Western authors, and especially French ones, in an artistic school known as

Decolonization and modern collaboration

The 20th century was marked by the French difficulties during

Since then, contacts have resumed, and France has remained a strong economic partner to Asian countries. French exports include nuclear power technologies, advanced transportation technologies such as Airbus or TGV, food products, and consumer industries. Asia in turn finds in France a receptive market for its manufactured goods.

Gallery

-

A TGV-based Korea Train Express train

-

TheArmée de l'Air.

-

A Louis Vuitton store in Hong Kong

See also

Notes and references

- .

- .

- ^ .

- ^ Boardman, p. 308

- .

- ISBN 978-0-631-20309-4.

- ISBN 9781417931736.

- ISBN 978-0-521-25603-2.

- ^ Goodrich, Samuel Griswold (1856). A History of All Nations, from the Earliest Periods to the Present Time; Or, Universal History: in which the History of Every Nation, Ancient and Modern, is Separately Given: Illustrated by 70 Stylographic Maps and 700 Engravings. Miller, Orton & Mulligan.

- ISBN 978-0-19-283340-2.

- ISBN 978-0-19-820288-2.

- ISBN 978-1-58843-551-4.

- ISBN 978-0-89622-537-4.

- ^ "The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 1, C.500-c.700".

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4529-1082-6.

- ^ "Warfare and Society in the Barbarian West 450-900".

- ^ "Life of the Fathers".

- ISBN 978-1-4529-1215-8.

- ISBN 978-0-299-08704-3.

- J.B. Bury, The Invasion of Europe by the Barbarians, lecture IX (e-text) Archived 2009-02-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "A History of the Alans in the West".

- ISBN 978-1-57958-282-1.

- ^ Fletcher, p. 53

- ^ a b "When Worlds Collide".

- ^ "The Oliphant".

- ISBN 978-0-472-06186-0.

- ISBN 978-3-11-019229-2.

- ISBN 0801492645.

- ISBN 9780792340669.

- ^ Fletcher, p. 55

- ISBN 978-0-19-820291-2.

- ISBN 9780520042063.

- ^ a b Miller, p. 2

- ISBN 978-1-4067-7272-2.

- ISBN 9780559388538.

- ^ Lamb, p. 228

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam, p. 328

- ^ Merriman, p. 132

- ^ a b c d e f "RELATIONS WITH PERSIA TO 1789". Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d "FRANCE iii. RELATIONS WITH PERSIA 1789–1918". Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ISBN 9780275968915.

- ^ John F. Baddeley. "The Russian Conquest of the Caucasus". Longman, Green and Co., London: 1908, p. 90

- ISBN 9780275974701.

- ^ ISBN 9780934211581.

- ^ Schom 1998, pp. 72–73

- ^ ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0

- ^ a b c d e f Dodwell, H. H., ed. (1933). The Cambridge History of the British Empire. Vol. IV: British India, 1497–1858. Cambridge University Press. p. 61.

- ISBN 978-81-206-0710-1.

- ^ "Explorers and Colonies".

- ^ "The Catholic Encyclopedia".

- ^ ISBN 978-0-226-46765-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-226-46765-8.

- ISBN 978-1-84331-004-4.

The account ... François Martin de Vitré made of their experience incited the king to create a company in the image of that of the United Provinces.

- ^ Butler's Lives of the Saints by Alban Butler, Paul Burns, p. 259

- ISBN 978-1-61204-339-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8387-5449-8.

- ^ Colbert, Mercantilism, and the French Quest for Asian Trade by Ames, Glenn J. Northern Illinois University Press [1][permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Pope, G. U. (George Uglow) (1880). A text-book of Indian history : with geographical notes, genealogical tables, examination questions, and chronological, biographical, geographical, and general indexes for the use of schools, colleges, and private students. Oxford University. London : W.H. Allen.

- ^ Frazer, Robert Watson (1897). British India. University of Michigan. New York, G. P. Putnam's sons; [etc., etc.]

- ^ ""Eastern Magnificence & European Ingenuity"".

- ^ "The Meeting of Eastern and Western Art".

- ISBN 0-674-01872-9, p. 85

- ISBN 0-7425-3815-X, p. 125

- ^ Europe and Burma: A Study of European Relations with Burma- p. 62 by Daniel George Edward Hall – 1945: "Dupleix promised them men and munitions, but before deciding how far to commit himself he sent over his agent, the Sieur de Bruno, to Pegu".

- ^ "Power and Plenty".

- ^ "Paris as it was and as it is".

- ^ "The Industry of Nations".

- ^ "Sloan's Architecture - The Late Georgian Period".

- ^ Hanna, p. 44

- ^ Hanna, p. 45

- ^ Hanna, pp. 45–47

- ISBN 978-0-415-20289-3.

- ^ "The Vietnamese Response to French Intervention, 1862-1874".

- ^ "The Last Emperors of Vietnam".

- ^ Tucker, p. 27

- ^ "French Policy in Japan During the Closing Years of the Tokugawa Regime".

- ISBN 9780203132234.

- .

Bibliography

- Boardman, John The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity, Princeton 1993 ISBN 0-691-03680-2

- Boutin, Aimée, and Elizabeth Emery, eds. "Cultural Exchange and Creative Identity: France/Asia in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries," , L'Esprit Créateur, The International Quarterly of French and Francophone Studies, Volume 56, Number 3, Fall 2016,

- Cotterell, Arthur. Western Power in Asia: Its Slow Rise and Swift Fall, 1415–1999 (John Wiley & Sons, 2010).

- Fletcher, Richard, 2004, The Cross and the Crescent, ISBN 978-0-14-101207-0

- ISBN 0-7946-0272-X.

- ISBN 1-4067-7272-0

- Miller, William. The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801–1927 Routledge, 1966 ISBN 0-7146-1974-4

- Lamb, Harold. Suleiman the Magnificent – Sultan of the East READ BOOKS, 2008 ISBN 1-4437-3144-7

- Lee, Robert. France and the exploitation of China, 1885–1901: A study in economic imperialism (Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1989).

- McAbe, Ina Baghdiantz 2008 Orientalism in early Modern France Berg ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. A History of Medieval Spain Cornell University Press, 1983 ISBN 0-8014-9264-5

- Starostina, Natalia. "Engineering the Empire of Images: Constructing Railways in Asia before the Great War." Southeast Review of Asian Studies 31 (2009): 181–206.

- Tucker, Spencer C. Vietnam University Press of Kentucky (1999). ISBN 0-8131-0966-3.

- French & Francophone Studies, Volume 21, 2017 – Issue 1: France-Asia.