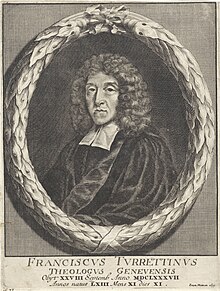

Francis Turretin

Francis Turretin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 October 1623 |

| Died | 28 September 1687 (aged 63) |

| Occupation | Theologian |

Francis Turretin (17 October 1623 – 28 September 1687; also known as François Turrettini) was a Genevan-Italian

Turretin is especially known as a zealous opponent of the moderate Calvinist

Life

Francis was the son of Bénédict Turrettini,[1] and like his father, was born in Geneva. Their ancestor (Bénédict's father), Francesco Turrettini the elder, had left his native Lucca in 1574 and settled in Geneva in 1592.

Francis studied theology at Geneva

Works

His Institutio Theologiae Elencticae (3 parts, Geneva, 1679–1685) is an example of

Turretin greatly influenced the

Free Choice

Along the lines of Reformed theology, Turretin argues that after the fall human beings did not lose the faculty of will itself. "The inability to do good is strongly asserted, but the essence of freedom is not destroyed" (Institutio theologiae elencticae, 10.2.9). They still have liberty which is not repugnant to certain kinds of necessity. For Turretin, neither the entities of the will nor the intellect are either the sole faculty of free will, which is rather conceived of their plurality as a mixed faculty. "As it belongs to the intellect with regard to the decision of choice, so it belongs to the will with regard to freedom" (Institutio theologiae elencticae, 10.1.4). Turretin distinguishes six kinds of necessity (Institutio, 10.2.4–9): physical necessity, necessity of coercion, necessity of dependence on God, rational necessity, moral necessity, and necessity of event. The first two among these six necessities are incompatible with freedom, whereas the latter four are not only compatible with freedom but perfect it. For example, treating upon the compatibility of moral necessity, Turretin asserts, despite the fact that a will can be rendered "slavish" if determined by habit to a manner of action, that "this servitude by no means overthrows the true and essential nature of liberty" (Institutio theologiae elencticae, 10.2.8). For Turretin, freedom does not arise from an indifference of the will. No rational beings are indifferent to good and evil. The will of an individual human being is never indifferent in the sense of possessing an equilibrium, either before or after the fall. Turretin defines freedom with the notion of rational spontaneity (Institutio, 10.2.10–11). [5]

Turretin's doctrine of freedom appears to be similar to that of Scotus in that both of them endorse Aristotelian logic: the distinction between the necessity of the consequent (necessitas consequentis) and the necessity of the consequence (necessitas consequentiae); the distinction between in sensu composito and in sensu diviso. It is not Scotus's notion of synchronic contingency but Aristotle's modal logic which is incorporated into Turretin's doctrine of freedom. Moreover, the Scotistic ideas about necessity and indifference differ greatly from those of Turretin. Turretin develops the discussion on necessity and relates it to his argument about human freedom of choice. His careful rejection of the notion of indifference in the doctrine of freedom creates a big gap between his doctrine and that of Scotus. Turretin's teaching of contingency emphasizes the sovereign act of God in the process of conversion, whereas Scotus's contingency theory blurs it. Turretin is not a Scotist, but a Reformed theologian standing in a more "generic Aristotelian tradition."[6]

English translations

- Institutes of Elenctic Theology. Translated by George Musgrave Giger, edited by James T. Dennison, Jr.; 3 volumes (1992-1997). ISBN 0-87552-451-6

- Justification an excerpt from Turretin's Institutes (2004). ISBN 0-87552-705-1

- The Atonement of Christ. Translated by James R. Willson (1978). ISBN 0-8010-8842-9

Notes

- ^ a b c Turrettini, François, in the Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 483.

- ^ a b Spencer 2000, p. 512.

- ^ a b Spencer 2000, p. 513.

- ^ Woo, B. Hoon (2016). "The Difference between Scotus and Turretin in Their Formulation of the Doctrine of Freedom". Westminster Theological Journal. 78: 263.

- ^ Woo, B. Hoon (2016). "The Difference between Scotus and Turretin in Their Formulation of the Doctrine of Freedom". Westminster Theological Journal. 78: 268–69.

Bibliography

- Spencer, Stephen R. (2000). "TURRETIN, FRANČOIS". In Carey, Patrick W.; Lienhard, Joseph T. (eds.). Biographical Dictionary of Christian Theologians. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 1-56563-798-4.

This article includes content derived from the public domain Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, 1914.

External links

- Works by Francis Turretin at Post-Reformation Digital Library

- Brief Biography of Turretin – a brief biography of Francis Turretin based on an oral address given by his nephew, and translated into English

- Excerpts from Turretin's Institutes in English:

- "The Holy Scriptures" – on the Bible

- "Forensic Justification" – on how one is made right with God

- "On Predestination of the Elect of God"

- Article on the Turretin family and the Institutes from the Princeton Review (July 1848)

- "Covenant Concepts in Francis Turretin's Institutes of Elenctic Theology" by C. Matthew McMahon

- "Turretin on Justification"[permanent dead link] an audio series by John Gerstner, long-time professor of church history.

- Woo, B. Hoon (2016). "The Difference between Scotus and Turretin in Their Formulation of the Doctrine of Freedom". Westminster Theological Journal. 78: 249–69.