Franconia

Franconia

| |

|---|---|

|

UTC+2 (CEST ) |

Franconia (German: Franken, pronounced [ˈfʁaŋkŋ̍] ⓘ;

Those parts of the

Franconia's largest city is Nuremberg, which is contiguous with Erlangen and Fürth, with which it forms the Franconian conurbation with around 1.3 million inhabitants. Other important Franconian cities are Würzburg, Bamberg, Bayreuth, Ansbach and Coburg in Bavaria, Suhl and Meiningen in Thuringia, and Schwäbisch Hall in Baden-Württemberg.

The German word Franken—Franconians—also refers to the

Etymology

The German name for Franconia, Franken, comes from the

The name of the Franks in turn derives from a word meaning "daring, bold", cognate with old Norwegian frakkr, "quick, bold".[5] Franks from the Middle and Lower Rhine gradually gained control of (and so gave their name to) what is now Franconia during the 6th to 8th centuries.[6] English distinguishes between Franks (the early medieval Germanic people) and Franconians in reference to the high medievalGeography

Overview

The Franconian lands lie principally in Bavaria, north and south of the sinuous

The landscape is characterized by numerous

In the east, the

In the west, Franconia proper comprises the

The two largest cities of Franconia are Nuremberg and Fürth. Though located on the southeastern periphery of the area, the Nuremberg metropolitan area is often identified as the economic and cultural centre of Franconia. Further cities in Bavarian Franconia include Würzburg, Erlangen, Bayreuth, Bamberg, Aschaffenburg, Schweinfurt, Hof, Coburg, Ansbach and Schwabach. The major (East) Franconian towns in Baden-Württemberg are Schwäbisch Hall on the Kocher — the imperial city declared itself "Swabian" in 1442 — and Crailsheim on the Jagst river. The main towns in Thuringia are Suhl and Meiningen.

-

Rothenburg is one of the best known towns in Franconia

-

Walberla in Franconia

-

Water wheel at the Regnitz

-

Nuremberg is the largest city of Franconia

-

Aerial view of the Veste Coburg

Extent

Here: the vestry of Meiningen's municipal church in South Thuringia. The Franconian Rake may be seen on the left

Franconia may be distinguished from the regions that surround it by its peculiar historical factors and its cultural and especially linguistic characteristics, but it is not a political entity with a fixed or tightly defined area. As a result, it is debated whether some areas belong to Franconia or not. Pointers to a more precise definition of Franconia's boundaries include: the territories covered by the former

The following regions are counted as part of Franconia today: the Bavarian

In individual cases the membership of some areas is disputed. These include the Bavarian language area of Alt-Eichstätt[8] and the Hessian-speaking[9] region around Aschaffenburg, which was never part of the Franconian Imperial Circle. The affiliation of the city of Heilbronn, whose inhabitants do not call themselves Franks,[10] is also controversial. Moreover, the sense of belonging to Franconia in the Frankish-speaking areas of Upper Palatinate, South Thuringia[11] and Hesse is sometimes less marked.

Administrative divisions

The region of Franconia is divided among the states of Hesse, Thuringia, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg. The largest part of Franconia, both by population and area, belongs to the Free State of Bavaria and is divided into the three administrative regions (Regierungsbezirke) of Middle Franconia (capital: Ansbach), Upper Franconia (capital: Bayreuth) and Lower Franconia (capital: Würzburg). The name of these regions, as in the case of Upper and Lower Bavaria, refers to their situation with respect to the river Main. Thus Upper Franconia lies on the upper reaches of the river, Lower Franconia on its lower reaches and Middle Franconia lies in between, although the Main itself does not flow through Middle Franconia. Where the boundaries of these three provinces meet (the 'tripoint') is the Dreifrankenstein ("Three Franconias Rock").[12] Small parts of Franconia also belong to the Bavarian regions of Upper Palatinate and Upper Bavaria.

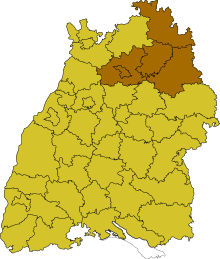

The Franconian territories of

The Franconian parts of Thuringia (Henneberg Franconia) lie within the Southwest Thuringia Planning Region.

The Franconian regions in Hesse form the smaller parts of the districts of Fulda (Kassel region) and the Odenwaldkreis (Darmstadt region), or lie on the borders with Bavaria or Thuringia.

Rivers and lakes

The two most important rivers of the region are the

The

Hills, mountains and plains

Several

In addition to the hill and mountain ranges, there are also several very level areas, including the Middle Franconian Basin and the Hohenlohe Plain. In the south of Franconia are smaller parts of the flat Nördlinger Ries, one of the best preserved impact craters on earth.

Forests, reserves, flora and fauna

Franconia's flora is dominated by deciduous and coniferous forests. Natural forests in Franconia occur mainly in the ranges of the Spessart, Franconian Forest, Odenwald and Steigerwald. The Nuremberg Reichswald is another great

Franconia has several regions with sandy habitats that are unique for south Germany and are protected as the so-called Sand Belt of Franconia or

Other

In 1991

Like large parts of Germany, Franconia only has a few large species of wild animal. Forest dwellers include various species of

Geology

General

Only in the extreme northeast of Franconia and in the Spessart are there

A substantially larger part of the shallow subsurface in Franconia comprises

The Mesozoic sediments have been deposited in largescale basin areas. During the Triassic, the Franconian part of these depressions was often part of the mainland, in the Jurassic it was covered for most of the time by a

Fossils

The oldest

Better known and more highly respected fossil finds in Franconia come from the unfolded sedimentary rocks of the Triassic and Jurassic. The

As early as the first decade of the 19th century

In Franconia's middle

Far more famous than Plateosaurus, Placodus and Nothosaurus is the

An inglorious episode in the history of paleontology took place in Franconia: fake fossils, known as Beringer's Lying Stones, were acquired in the 1720s by Würzburg doctor and naturalist, Johann Beringer, for a lot of money and then described in a monograph, along with genuine fossils from the Würzburg area. However, it is not entirely clear whether the Beringer forgeries were actually planted or whether he himself was responsible for the fraud.[41]

Climate

Franconia has a

Quality of life

Franconia, as part of Germany, has a high

History

Name

Franconia is named after the

At the beginning of the 10th century a Duchy of Franconia (German: Herzogtum Franken) was established within

Early history and Antiquity

Fossil finds show that the region was already settled by

Under the emperors,

By contrast, it was the Burgundians who settled on the Lower and Middle Main.[57] Many of these hill forts appear to have been destroyed, however, no later than 500 A.D. The reasons are not entirely clear, but it could have been as a result of invasions by the Huns which thus triggered the Great Migration. In many cases, however, it was probably conquest by the Franks that spelt the end of these hilltop settlements.[56]

Middle Ages

With their victories over the heartlands of the Alamanni and

In the mid-9th century the

Meanwhile, the inhabitants of parts of present-day Upper and Middle Franconia, who were not under the control of Würzburg, probably also considered themselves to be Franks at that time, and certainly their dialect distinguished them from the inhabitants of Bavaria and Swabia.[61]

Unlike the other stem duchies, Franconia became the homeland and power base of East Frankish and German kings after the

From the 12th century

Successor states of East Francia

As of the 13th century, the following states, among others, had formed in the territory of the former Duchy:

|

|

Modern Period

Early Modern Period

On 2 July 1500 during the reign of Emperor

Members of the Franconian Circle included the imperial cities, the prince-bishoprics, the Bailiwick of Franconia of the Teutonic Order and several counties. The

Franconia played an important role in the spread of

In 1525, the burden of heavy taxation and socage combined with new, liberal ideas that chimed with

From 1552, Margrave

In 1608, the reformed princes merged into a so-called

Franconia never developed into a unified territorial state, because the patchwork quilt of small states (

Later Modern Period

Most of modern-day Franconia became part of Bavaria in 1803 thanks to Bavaria's alliance with

19th century

In 1803, what was to become the

In 1814, as a result of the

From 1836 to 1846, the Kingdom of Bavaria built the

20th century

After the

During the

Like all parts of the German Reich, Franconia was badly affected by

Following the

The state of

By contrast, the state of Thuringia was restored by the

In the years from 1971 to 1980 an administrative reform was carried out in Bavaria with the aim of creating more efficient municipalities (

Since Die Wende, new markets have opened up for the Franconian region of Bavaria in the new (formerly East German) federal states and the Czech Republic, enabling the economy to recover.[118] Today, Franconia is in the centre of the EU (at Oberwestern near Westerngrund; geographical centre of the EU 50°07′02″N 9°14′52″E / 50.117286°N 9.247768°E).[119]

Contemporary Franconia

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

While

The city of

Population

A large part of the population of Franconia, which has a population of five million,

The

Towns and cities

With the exception of Schwäbisch Hall, all cities in Franconia and all towns with a population of over 40,000 are within the Free State of Bavaria. By far the largest city in Franconia is Nuremberg with more than 500,000 inhabitants. The other three major cities are Fürth, Würzburg and Erlangen. In Middle Franconia, in the metropolitan region of Nuremberg there is a densely populated urban area consisting of Nuremberg, Fürth, Erlangen and Schwabach with arround 1.4 million inhabitants. Nuremberg is the fourteenth largest city in Germany and the second largest in Bavaria.[123]

The largest settlements in Baden-Württemberg's Franconian region are Schwäbisch Hall (41,898 pop.) and Crailsheim (35,760) Öhringen (25,388) and Bad Mergentheim (24,564)[124] The largest places in the Thuringian part are Suhl (37,009), Meiningen (25,177) and Sonneberg (23,507).[125]

The largest place in the Hessian part of Franconia is

In the

- 25 largest cities in Franconia

| 2022 Rank |

City | State | 2000 | 2020 | 2022 | growth (2000–2020) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Nuremberg | Bavaria | 488,400 | 515,543 | 523,026 | +5.6% |

|

| 2. | Fürth | Bavaria | 110,477 | 128,223 | 131,433 | +16.1% |

|

| 3. | Würzburg | Bavaria | 127,966 | 126,954 | 127,810 | -0.8% |

|

| 4. | Erlangen | Bavaria | 100,778 | 112,385 | 116,562 | +11.5% |

|

| 5. | Bamberg | Bavaria | 69,036 | 76,674 | 79,935 | +11.1% |

|

| 6. | Bayreuth | Bavaria | 74,153 | 74,048 | 74,506 | -0.1% |

|

| 7. | Aschaffenburg | Bavaria | 67,592 | 70,858 | 72,444 | +4.8% |

|

| 8. | Schweinfurt | Bavaria | 54,325 | 53,319 | 54,675 | -1.9% |

|

| 9. | Hof (Saale)

|

Bavaria | 50,741 | 45,173 | 46,656 | -12.3% |

|

| 10. | Ansbach | Bavaria | 40,163 | 41,681 | 42,221 | +3.6% |

|

| 11. | Schwäbisch Hall | Baden-Württemberg | 35,192 | 40,679 | 41,898 | +15.6% | |

| 12. | Coburg | Bavaria | 43,277 | 40,842 | 41,842 | -6.2% |

|

| 13. | Schwabach | Bavaria | 37,947 | 41,056 | 41,227 | +7.6% |

|

| 14. | Suhl | Thuringia | 48,025 | 36,395 | 37,009 | -24.2% |

|

| 15. | Crailsheim | Baden-Württemberg | 32,063 | 34,661 | 35,760 | +8.1% |

|

| 16. | Forchheim | Bavaria | 30,665 | 32,374 | 32,972 | +5.5% |

|

| 17. | Lauf an der Pegnitz | Bavaria | 25,770 | 26,434 | 26,420 | +2.6% |

|

| 18. | Zirndorf | Bavaria | 24,950 | 25,748 | 26,234 | +3.2% |

|

| 19. | Kulmbach | Bavaria | 28,258 | 25,781 | 25,818 | -8.8% |

|

| 20. | Öhringen | Baden-Württemberg | 22,208 | 24,925 | 25,388 | +12,2% |

|

| 21. | Roth | Bavaria | 24,858 | 25,323 | 25,367 | +1,9% |

|

| 22. | Meiningen | Thuringia | 22,240 | 25,097 | 25,177 | +12,8% |

|

| 23. | Bad Mergentheim | Baden-Württemberg | 22,172 | 24,034 | 24,564 | +8,4% |

|

| 24. | Herzogenaurach | Bavaria | 23,108 | 23,616 | 24,404 | +2.2% |

|

| 25. | Sonneberg | Thuringia | 24,837 | 23,229 | 23,507 | –6.5% |

|

Language

German is the official language and also the lingua franca. Numerous other languages are spoken that come from other language regions or the native countries of immigrants.[citation needed]

Religions

Christianity

The proportion of

The

Following the success of

The influx of immigrants from Eastern Europe has also seen the establishment of an Orthodox community in Franconia. The Romanian Orthodox Metropolis of Germany, Central and Northern Europe has its headquarters in Nuremberg.[citation needed]

Judaism

Before the

In 1818, about 65% of Bavarian Jews lived in the Bavarian part of Franconia,[136] today there are Jewish communities only in Bamberg, Bayreuth, Erlangen, Fürth, Hof, Nuremberg and Würzburg[137] and in Heilbronn in Baden-Württemberg.

Islam

Adherents of Islam continue to grow, especially in the larger cities, due to the influx of

Culture

Franconia has almost 300 small breweries.[138]

The northwestern parts, the areas around the river

-

Three Nuremberger Bratwürste in a roll (Drei im Weckla)

-

Schlenkerla Rauchbier straight from the cask

-

Franconian wine is traditionally filled up in Bocksbeutels

-

Fried Carp with beer and salad

Tourism

The

Cycling along the large rivers is very popular, for example along the Main Cycleway, the first German long distance cycleway to be awarded five stars by the Allgemeiner Deutscher Fahrrad-Club (ADFC). The Tauber Valley Cycleway, a 101 kilometre-long cycle trail in Tauber Franconia, was the second German long distance cycleway to receive five stars.[143]

See also

Germany portal

Germany portal- East Franconian German

- Franconia (wine region)

- Franconian Flag

- Franconian Rake

- Fränkel

Notes

- German Kingdomand of which the whole of the Duchy of Franconia was a part.

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d Karten zur Geschichte Bayerns: Jutta Schumann / Dieter J. Weiß, in: Edel und Frei. Franken im Mittelalter, ed. by Wolfgang Jahn / Jutta Schumann / Evamaria Brockhoff, Augsburg, 2004 (Veröffentlichungen zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 47/04), pp. 174–176, Cat. No. 51. Siehe Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Rudolf Endres: "Der Fränkische Reichskreis". In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte, Regensburg, 2003, p. 6, see online version (PDF).

- ^ Manfred Treml: "Das Königreich Bayern (1806–1918)". In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, 1989, pp. 22–25, here: p. 22.

- ^ Entry Franken in the Deutsches Wörterbuch. Boris Paraschkewow: Wörter und Namen gleicher Herkunft und Struktur. Lexikon etymologischer Dubletten im Deutschen. Berlin, 2004, p. 107

- ^ Ulrich Nonn: Die Franken. Stuttgart, 2010, pp. 11–14 ff.

- ^ Friedrich Helmer: Bayern im Frankenreich (5.–10. Jahrhundert). In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, herausgegeben vom Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte als Heft 9 der Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 4–6, here: p. 4

- ^ a b Rudolf Endres: Der Fränkische Reichskreis. In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the House of Bavarian History, Regensburg, 2003, p. 37, see online version Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (pdf)

- ^ a b c Was ist fränkisch? Wie eine Region definiert wird, Bayerischer Rundfunk, Bayern 2

- ^ Sprachatlas der BLO Archived 2012-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ Ulrich Maier (Justinus-Kerner-Gymnasium Weinsberg): Schwäbisch oder fränkisch? Mundart im Raum Heilbronn Bausteine zu einer Unterrichtseinheit. see online pdf Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ominöses Frankenbewusstsein", Süddeutsche Zeitung dated 10 February 2013, retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Dreifrankenstein Archived 2016-03-22 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ BfNmap

- ^ Sandwege Archived 2016-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, Sandachse Franken, retrieved 23 May 2014

- ^ Naturpark Bayerische Rhön Archived 2016-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2 Jun 2014.

- ^ a b "www.br-online.de: Bund Naturschutz zu Steigerwald – "Imagegewinn durch Nationalpark"". Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Press report on the rejected Steigerwald National Park at BR-online, Studio-Franken - ^ Wir über uns Archived 2016-07-03 at the Wayback Machine, www.naturpark.de, retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Naturparks in Franken Archived 2016-07-30 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2 June 2014.

- ^ Biosphärenreservat Rhön Archived 2016-04-19 at the Wayback Machine, Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz, retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Bayerns schönste Geotope Archived 2016-07-29 at the Wayback Machine, Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz, retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ^ Karte der Vogelschutzgebiete Archived 2016-06-17 at the Wayback Machine: Mittelfranken, stellvertretend für alle Europäischen Vogelschutzgebieten in Franken

- ^ Fichtelgebirge Nature Park Archived 2016-06-11 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 2 Jun 2014.

- ^ Wildlife in Bavaria: The wolf - a Native Bavarian Archived 2016-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, Bayerischer Rundfunk, retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ a b Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler and Klaus fword (eds.): GeoBavaria. 600 Millionen Jahre Bayern. Internationale Edition. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 2004 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 4

- ^ Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler and Klaus fword. (eds.): GeoBavaria. 600 Millionen Jahre Bayern. Internationale Edition. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 2004 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 24

- ^ Alfons Baier, Thomas Hochsieder: Zur Stratigraphie und Tektonik des SE-Randes der Münchberger Gneismasse (Oberfranken) Archived 2016-09-07 at the Wayback Machine. Website of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg with a summary of the essay of the same name in the Geologischen Blättern für Nordost-Bayern, Vol. 39, No. 3/4, Erlangen, 1989

- ^ a b Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler and Klaus Schwerd (eds.): GeoBavaria. 600 million years Bavaria. International Edition. GeoBavaria. 600 Millionen Jahre Bayern. Internationale Edition. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 2004 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 26

- ^ Dickinson, Robert E (1964). Germany: A regional and economic geography (2nd ed.). London: Methuen, p 568. .

- ^ Walter Freudenberger: Tektonik: Deckgebirge nördlich der Donau. In: Walter Freudenberger, Klaus Schwerd (Red.): Erläuterungen zur Geologischen Karte von Bayern 1:500 000. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 1996 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 259-265

- ^ a b Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler and Klaus Schwerde. (eds.): Stefan Glaser, Gerhard Doppler und Klaus Schwerd (Red.): GeoBavaria. 600 Millionen Jahre Bayern. Internationale Edition. Bayerisches Geologisches Landesamt, Munich, 2004 (online Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine), p. 40 ff.

- ^ Hans-Georg Herbig, Thomas Wotte, Stefanie Becker: First proof of archaeocyathid-bearing Lower Cambrian in the Franconian Forest (Saxothuringian Zone, Northeast Bavaria). In: Jiři Žák, Gernold Zulauf, Heinz-Gerd Röhling (Hrsg.): Crustal evolution and geodynamic processes in Central Europe. Proceedings of the Joint conference of the Czech and German geological societies held in Plzeň (Pilsen), September 16–19, 2013. Schriftenreihe der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften. No. 82, 2013, p. 50 (full text: Researchgate)

- ^ Hartmut Haubold: Die Saurierfährten Chirotherium barthii Kaup, 1835 - das Typusmaterial aus dem Buntsandstein bei Hildburghausen/Thüringen und das "Chirotherium-Monument". Publication by the Natural History Museum, Schleusingen, vol. 21, 2006, pp. 3–31

- ^ a b Frank-Otto Haderer, Georges Demathieu, Ronald Böttcher: Wirbeltier-Fährten aus dem Rötquarzit (Oberer Buntsandstein, Mittlere Trias) von Hardheim bei Wertheim/Main (Süddeutschland). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B. No. 230, 1995, online Archived 2017-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Laura K. Säilä: The Osteology and Affinities of Anomoiodon liliensterni, a Procolophonid Reptile from the Lower Triassic Buntsandstein of Germany. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 28, No. 4, 2008, pp. 1199–1205, doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1199

- ^ Friedrich von Huene: Ueber die Procolophoniden, mit einer neuen Form aus dem Buntsandstein. Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie. 1911 issue, 1911, pp. 78–83

- ^ Rainer R. Schoch: Comparative osteology of Mastodonsaurus giganteus (Jaeger, 1828) from the Middle Triassic (Lettenkeuper: Longobardian) of Germany (Baden-Württemberg, Bayern, Thüringen). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Series B. No. 278, 1999, pp. 21 and 27 (PDF 3,6 MB)

- ^ Emily J. Rayfield, Paul M. Barrett, Andrew R. Milner: Utility and Validity of Middle and Late Triassic 'Land Vertebrate Faunachrons'. In: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Vol. 29, 2009, No. 1, pp. 80–87, doi:10.1671/039.029.0132.

- ^ Olivier Rieppel: The genus Placodus: Systematics, Morphology, Paleobiogeography, and Paleobiology. Fieldiana Geology, New Series, No. 31, 1995, doi:10.5962/bhl.title.3301.

- ^ Olivier Rieppel, Rupert Wild. A Revision of the Genus Nothosaurus (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Germanic Triassic, with Comments on the Status of Conchiosaurus clavatus. Fieldiana Geology, New Series, No. 34, 1996. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.2691

- ^ Birgit Niebuhr: Wer hat hier gelogen? Die Würzburger Lügenstein-Affaire. Fossilien. No. 1/2006, 2006, S. 15–19 ("PDF" (PDF). Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved 2016-01-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) 886 kB) - ^ Mittelwerte und Kenntage der Lufttemperatur Archived 2016-07-01 at the Wayback Machine, Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt, retrieved 23 May 2014.

- Spiegel Online, retrieved 23 May 2014

- ^ Mittelwerte des Gebietsniederschlags Archived 2016-07-01 at the Wayback Machine, www.lfu.bayern.de, Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt, retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ a b "mercer.de". Archived from the original on 2012-01-18. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- Focus Online, retrieved 10 September 2014

- ^ Deutsche Post Glücksatlas Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Glücksatlas 2013: Franken sind so unglücklich wie nie zuvor Archived 2016-09-17 at the Wayback Machine. Nordbayern.de, published 5 November 2013, retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Geschiedenis van het Nederlands by M van der Wal, 1992

- ^ Gerhard Köbler, Historisches Lexikon der deutschen Länder, Darmstadt 1999, pp. 173–174

- ^ Gerhard Köbler, Historisches Lexikon der deutschen Länder, Darmstadt 1999

- ^ Die Höhlenruine von Hunas Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, Archäologisches Lexikon, retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Hans-Peter Uenze, Claus-Michael Hüssen: Vor- und Frühgeschichte. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 3–46, here: pp. 17ff.

- ^ Josef Motschmann: Altenkunstadt - Heimat zwischen Kordigast und Main. Gemeinde Altenkunstadt, Altenkunstadt, 2006, p. 10

- ^ Peter Kolb, Ernst-Günter Krenig: Unterfränkische Geschichte. Von der germanischen Landnahme bis zum hohen Mittelalter., Vol. 1. Würzburg, 1989; second edition: 1990, pp. 27–37.

- ^ a b Wilfried Menghin: Grundlegung: Das frühe Mittelalter. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 47–69, here: p. 60

- ^ a b Wilfried Menghin: Grundlegung: Das frühe Mittelalter. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3. Bd., 1. Teilbd: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 47–69, here: S. 55.

- ^ Franz-Joseph Schmale, Wilhelm Störmer: Die politische Entwicklung bis zur Eingliederung ins Merowingische Frankenreich. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 89–114, here: p. 80.

- ^ Friedrich Helmer: Bayern im Frankenreich (5. - 10. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 4–6, here: p. 6

- ^ a b Josef Kirmeier: Bayern und das Deutsche Reich (10.-12. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 7–9, here: p. 7

- ^ a b Karten zur Geschichte Bayerns: Jutta Schumann / Dieter J. Weiß, in: Edel und Frei. Franken im Mittelalter, ed. by Wolfgang Jahn / Jutta Schumann / Evamaria Brockhoff, Augsburg, 2004 (Veröffentlichungen zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 47/04), pp. 174–176, Cat. No. 51. See Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Dieter Weiß: Bamberg, Hochstift: Territorium und Struktur. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ^ Meininger Urkundenbuch Nos. 3-5. Reg. Thur. I Nos. 614, 616, 618-. Stadtarchiv Meiningen.

- ^ Otto Spälter: Nürnberg, Burggrafschaft. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ^ Alois Gerlich, Franz Machilek: Die innere Entwicklung vom Interregnum bis 1800: Staat, Gesellschaft, Kirche Wirtschaft. - Staat und Gesellschaft. Erster Teil: bis 1500 In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 537–701, here: p. 602.

- ^ Alexander Schubert: Swabian League of Cities. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ^ Rudolf Endres: Staat und Gesellschaft. Zweiter Teil: 1500-1800. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd, revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 702–781, here: pp. 752ff

- ^ Wilhelm Störmer: Die innere Entwicklung: Staat, Gesellschaft, Kirche, Wirtschaft. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, begr. von Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 210–315, here: p. 314.

- ^ a b Johannes Merz: Herzogswürde, fränkische. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ^ Rudolf Endres: Der Fränkische Reichskreis, In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte, Regensburg, 2003, p. 21, see online version Archived 2016-06-11 at the Wayback Machine (pdf)

- ^ Michael Henker: Bayern im Zeitalter von Reformation und Gegenreformation (16./17. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the Haus der Bayerischen Geschichte as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 14–17, here: p. 14

- ^ Pütter, John Stephen. An Historical Development of the Present Political Constitution of the Germanic Empire, Vol. 3, London: Payne, 1790, p. 156.

- ^ Rudolf Endres: Von der Bildung des Fränkischen Reichskreises und dem Beginn der Reformation bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden von 1555. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, edited by Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 451–472, here: pp. 455ff.

- ^ Endter-Bibeln Archived 2016-06-11 at the Wayback Machine, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Rudolf Endres: Von der Bildung des Fränkischen Reichskreises und dem Beginn der Reformation bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden von 1555. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, edited by Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol.: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, re-published by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 451–472, here: p. 467.

- ^ Birke Grießhammer: Verfolgt – gefoltert – verbrannt. Die Opfer des Hexenwahns in Franken., pp. 15 ff

- ^ Christian Hege: Königsberg in Bayern (Freistaat Bayern, Germany). In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- ^ Christian Neff: Nürnberg (Freistaat Bayern, Germany). In: Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online

- ^ Stadthistorische Streiflichter (24), www.wuerzburg.de, accessed 7 June 2014.

- ^ Rudolf Endres: Von der Bildung des Fränkischen Reichskreises und dem Beginn der Reformation bis zum Augsburger Religionsfrieden von 1555. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, ed. Max Spindler, 3 vols., 1 sub-vol: History of Franconia to the end of the 18th century, revised by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edition, Munich, 1997, pp. 451-472, here: p. 469

- ^ Michael Henker: Bayern im Zeitalter von Reformation und Gegenreformation (16./17. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the House of Bavarian History as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 14–17, here: p. 15

- ^ Rudolf Endres. Der Fränkische Reichskreis, In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the House of Bavarian History, Regensburg, 2003, p. 19, see online version (pdf)

- ^ Rudolf Endres: Vom Augsburger Religionsfrieden bis zum Dreißigjährigen Krieg. In: Handbuch der Bayerischen Geschichte, ed. Max Spindler, 3rd vol., 1st sub-vol: Geschichte Frankens bis zum Ausgang des 18. Jahrhunderts, revised by Andreas Kraus, 3rd revised edn., Munich, 1997, pp. 473–495, here: p. 490.

- ^ Michael Henker: Bayern im Zeitalter von Reformation und Gegenreformation (16./17. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the House of Bavarian History as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 14–17, here: p. 17

- ^ Aus Österreich vertrieben: Glaubensflüchtlinge in Franken Archived 2014-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, br.de, Bayerischer Rundfunk, retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ a b Karlheinz Scherr: Bayern im Zeitalter des Fürstlichen Absolutismus (17./18. Jahrhundert), In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns, published by the House of Bavarian History as Issue 9 of the Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur, pp. 18–21, here: p. 20

- ^ Rudolf Endres: Der Fränkische Reichskreis, In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the House of Bavarian History, Regensburg, 2003, p. 35, see online version Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (pdf)

- ^ Rudolf Endres: Der Fränkische Reichskreis, In: Hefte zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 29, published by the house of Bavarian History, Regensburg, 2003, p. 38, see online version Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (pdf)

- ^ a b c Preußen in Franken 1792 - 1806 Archived 2016-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, material from the State Exhibition in 1999 by the House of Bavarian History

- ^ Der Friede von Lunéville (1801) und der Reichsdeputationshauptschluss (1803), House of Bavarian History, accessed 7 June 2014.

- ^ a b Rheinbundakte, deutsche Fassung (1806), House of Bavarian History , retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Dietmar Willoweit: Reich und Staat: Eine kleine deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte, p. 70

- ^ Max Seeberger et al.: Wie Bayern vermessen wurde, booklets on Bavarian History and Culture, Volume 26, published by the House of Bavarian History in collaboration with the Deutsches Museum and Bavarian State Survey Office, Munich, Augsburg, 2001, pp. 11-12

- ^ Manfred Treml: Das Königreich Bayern (1806 - 1918). in: Political History of Bavaria, published by the House of Bavarian history as No. 9 of ten booklets on Bavarian History and Culture, 1989, pp. 22-25, here: p. 23

- ^ Fränkischer Reichskreis: So entstand der "Tag der Franken" Archived 2015-03-25 at the Wayback Machine, www.br.de, Bayerischer Rundfunk, retrieved 28 June 2014

- ^ a b Hans Maier: Die Franken in Bayern, p. 6, see pdf Archived 2016-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ Katharina Weigand: Gaibach. Eine Jubelfeier für die bayerische Verfassung von 1818? In: Alois Schmid, Katharina Weigand (eds.): Schauplätze der Geschichte in Bayern. Munich, 2003, pp. 291-308, here: p. 291

- ^ House of Bavarian History: deutsche Revolution von 1848/49, retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Edition Bayern: Industriekultur in Bayern, published by the House of Bavarian History, p. 123

- ^ a b Wolf Weigand: Bayern zur Zeit der Weimarer Republik und des Nationalsozialismus (1918 - 1945). In: Politische Geschichte Bayerns published by the House of Bavarian History as No. 9 of the booklets on Bavarian History and Culture, 1989, pp. 26-28, here: p. 26

- ^ Eckart Dietzfelbinger, Gerhard Liedke: Nürnberg - Ort der Massen. Das Reichsparteitagsgelände. Vorgeschichte und schwieriges Erbe. 1st edition, Berlin, 2004, p. 29

- ^ Werner Falk: Ein früher Hass auf Juden in Nürnberger Nachrichten, 25 March 2009.

- Deutsches Historisches Museum, retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ISBN 3-8062-1333-X.

- ^ Bamberg, die Altstadt als Denkmal: Denkmalschutz, Modernisierung, Sanierung, Moos, 1981, p. 172

- ^ Historischer Kunstbunker Archived 2016-08-30 at the Wayback Machine, the City Museums, retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ See map of the American zone

- ^ Annette Weinke: Nuremberg Trials. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ^ Bayerische Geschichte und Persönlichkeiten Archived 2014-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, Bayerisches Landesportal, retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Paul Sauer: Demokratischer Neubeginn in Not und Elend. Das Land Württemberg-Baden von 1945 bis 1952. Ulm, 1978, p. 91

- ^ Gründung des Landes Baden-Württemberg am 25. April 1952 Archived 2016-11-16 at the Wayback Machine, Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg

- ^ Walter Ziegler: Flüchtlinge und Vertriebene. In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ^ at-end-of-world-development-of-west German-zone border area-since-the-reunion Am Ende der Welt - Entwicklung des westdeutschen Zonenrandgebietes seit der Wiedervereinigung, Federal Agency for Civic Education, published 18 November 2013, retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ a b Steffen Raßloff: Geschichte Thüringens. Munich, 2010, p. 106

- ^ Werner Abelshauser: Deutsche Wirtschaftsgeschichte seit 1945. C.H. Beck, Munich, 2004, chapter on "Die Reparationsfrage", pp. 75-84.

- ^ Quellen zur Geschichte Thüringens. Der 17. Juni 1953 in Thüringen., The State Commissioner of Thuringia for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic and State Centre for Political Education, Thuringia, Sömmerda, 2003, p. 180

- ^ Document 15/5583 of the Bavarian Landtag Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine (pdf; 86 kB)

- ^ Frank Altrichter: Grenzlandproblematik (nach 1918). In: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns

- ^ Frank Müller. Westerngrund (LK: AB). The Navel of Europe in Franconia Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine radio report, Bayern 2, regionalZeit - Franken

- ^ "Predominantly Protestant and predominantly Catholic regions in Franconia, denomination distribution 1750" (in German). Retrieved 2024-03-24.

- ^ Based on the combined populations of the provinces of Middle, Upper and Lower Franconia in Bavaria as well as the counties of South Thuringia and Tauber Franconia.

- ^ Das Land Bayern: Menschen in Bayern - Tradition und Zukunft Archived 25 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine: www.bayern.de, Bayerisches Landesportal. Accessed 15 September 2022.

- ^ a b Genesis Online-Datenbank des Bayerischen Landesamtes für Statistik Tabelle 12411-003r Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes: Gemeinden, Stichtag (Einwohnerzahlen auf Grundlage des Zensus 2011) (from the 31st of December 2022)

- ^ Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg – Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht am 31. Dezember 2022 (from the 31st of December 2022) (CSV-File)]

- ^ Bevölkerung der Gemeinden vom Thüringer Landesamt für Statistik (from the 31st of December 2022)

- ^ Bevölkerung der hessischen Gemeinden (population figures from the 2011 census)

- ^ a b Karten zur Geschichte Bayerns: Helmut Flachenecker, in: Edel und Frei. Franken im Mittelalter, ed. by Wolfgang Jahn / Jutta Schumann / Evamaria Brockhoff, Augsburg, 2004 (Veröffentlichungen zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 47/04), pp. 308–313, Cat. No. 134. See House of Bavarian History Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Statistik, Thüringer Landesamt für. "Thüringer Landesamt für Statistik". tls.thueringen.de. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014.

- ^ a b Karten zur Geschichte Bayerns: Überwiegend protestantische und überwiegend katholische Gebiete in Franken. In: Kirmeier, Josef et al. (ed.): 200 Jahre Franken in Bayern. Aufsatzband zur Landesausstellung 2006, Augsburg, 2006 (Veröffentlichungen zur Bayerischen Geschichte und Kultur 51), see House of Bavarian History Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ferdinand Lammers, Geschichte der Stadt Erlangen, Erlangen, 1834 (1997 reprint), pg. 17.

- ISBN 3-921590-69-8

- ^ Steven M. Lowenstein: Alltag und Tradition: Eine fränkisch-jüdische Geographie. In: Die Juden in Franken. (= Studien zur Jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur in Bayern, Volume 5) Munich, 2012 pp. 5-24, here: pg. 5.

- ^ Steven M. Lowenstein: Alltag und Tradition: Eine fränkisch-jüdische Geographie. In: Die Juden in Franken. (= Studien zur Jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur in Bayern, Volume 5) Munich, 2012 pp. 5-24, here: pp. 5-6.

- ^ Hohenloher waren die ersten Opfer Archived 2016-09-17 at the Wayback Machine at stimme.de

- ISBN 3-8260-2226-2

- ^ Steven M. Lowenstein: Alltag und Tradition: Eine fränkisch-jüdische Geographie. In: Die Juden in Franken. (= Studien zur Jüdischen Geschichte und Kultur in Bayern, Volume 5) Munich, 2012 pp. 5-24, here: pg. 14

- ^ Jewish communities in Bavaria, State Association of Jewish communities in Bavaria, retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Waltman, Fred. "Online guide to Bamberg and the Breweries of Franconia". www.franconiabeerguide.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ www.romantisches-franken.de; retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ a b c Franken. Allianz Reiseführer, 2011, pp. 12ff

- ^ www.frankentourismus.de Archived 29 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ www.romantischestrasse.de Archived 29 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ Touristikgemeinschaft Liebliches Taubertal: Fünf Sterne für den "Klassiker" Archived 12 September 2012 at archive.today In: Tauber-Zeitung. Online at www.swp.de. 31 October 2009; retrieved 6 April 2010.

Bibliography

- Andert, Reinhold. Der fränkische Reiter. Dingsda-Verlag Querfurt, Leipzig, 2006, ISBN 3-928498-92-4.

- Beckstein, Günther (text) and Erich Weiß (photographs). Franken, Mein Franken - Impressionen aus meiner Heimat. Bamberg, 2009, ISBN 978-3-936897-61-6.

- Bernet, Claus. Himmlisches Franken. Norderstedt, 2012, ISBN 978-3-8482-3041-9.

- Blessing, Werner K. and Dieter Weiß (eds.): Franken. Vorstellung und Wirklichkeit in der Geschichte. (= Franconia. Appendices to the Yearbook for Franconian State Research, Vol. 1), Neustadt (Aisch), 2003.

- Bogner, Franz X. Franken aus der Luft. Stürtz-Verlag Würzburg, 2008, ISBN 978-3-8003-1913-8.

- Bogner, Franz X. Oberfranken aus der Luft. Ellwanger-Verlag, 128 pages. Bayreuth, 2011, ISBN 978-3-925361-95-1.

- Bötzinger, Martin. Leben und Leiden während des Dreißigjährigen Krieges in Thüringen und Franken. Langensalza, ²1997, ISBN 3-929000-39-3.

- ISBN 0-06-017033-6.

- Elkar, Rainer S. Geschichtslandschaft Franken - wohlbestelltes Feld mit Lücken. In: Jahrbuch für Regionalgeschichte 23 (2005), pp. 145–158.

- Fischer,Berndt. Naturerlebnis Franken. Streifzüge durch eine Seelenlandschaft. Buch & Kunstverlag Oberpfalz, Amberg, 2001, ISBN 3-924350-91-4.

- Nestmeyer, Ralf: Franken. Ein Reisehandbuch. Michael-Müller-Verlag, Erlangen, 2013, ISBN 978-3-89953-775-8.

- Peters, Michael. Geschichte Frankens. Vom Ausgang der Antike bis zum Ende des Alten Reiches. Katz Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-938047-31-6 (c.f. review).

- Petersohn, Jürgen. Franken im Mittelalter. Identität und Profil im Spiegel von Bewußtsein und Vorstellung. (Vorträge und Forschungen, Sonderband 51), Ostfildern, 2008 (c.f. the review).

- ISBN 0-582-49034-0.

- Scherzer, Conrad. Franken, Land, Volk, Geschichte und Wirtschaft. Verlag Nürnberger Presse Drexel, Merkel & Co., Nuremberg, 1955, OCLC 451342119.

- Schiener, Anna. Kleine Geschichte Frankens. Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg, 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2131-6.

- Stützel, Ada. 100 berühmte Franken. Sutton Verlag, Erfurt, 2007, ISBN 978-3-86680-118-9.

- Wüst, Wolfgang (ed.): Frankens Städte und Territorien als Kulturdrehscheibe. Kommunikation in der Mitte Deutschlands. Interdisciplinary conference 29 to 30 September 2006 in Weißenburg i. Bayern (Mittelfränkische Studien 19) Ansbach, 2008, ISBN 978-3-87707-713-9.

External links

- Bezirk of Lower Franconia

- Government of Lower Franconia

- Bezirk of Middle Franconia

- Government of Middle Franconia

- Bezirk of Upper Franconia Archived 2020-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Government of Upper Franconia English pages available

- The Baden-Württemberg region of Heilbronn-Franken

- Dukes of Franconia

- Franconia images

- The Franconian Dictionary