Frederick Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard

PC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Governor-General of Nigeria | |||||||

| In office 1 January 1914 – 8 August 1919 | |||||||

| Preceded by | Office created | ||||||

| Succeeded by | Sir Hugh Clifford (as Governor) | ||||||

| Governor of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate | |||||||

| In office September 1912 – 1 January 1914 | |||||||

| Preceded by | Sir Charles Lindsay | ||||||

| Succeeded by | Office abolished | ||||||

| Governor of the Southern Nigeria Protectorate | |||||||

| In office September 1912 – 1 January 1914 | |||||||

| Preceded by | Sir Walter Egerton | ||||||

| Succeeded by | Office abolished | ||||||

| 14th Governor of Hong Kong | |||||||

| In office 29 July 1907 – 16 March 1912 | |||||||

| Monarchs | Edward VII George V | ||||||

| Colonial Secretary | Sir Francis Henry May Warren Delabere Barnes Sir Claud Severn | ||||||

| Preceded by | Sir Matthew Nathan | ||||||

| Succeeded by | Sir Francis Henry May | ||||||

| High Commissioner of the Northern Nigeria Protectorate | |||||||

| In office 6 January 1900 – September 1906 | |||||||

| Preceded by | Office created | ||||||

| Succeeded by | Sir William Wallace (acting) | ||||||

| Personal details | |||||||

| Born | 22 January 1858 British India | ||||||

| Died | 11 April 1945 (aged 87) Dorking, Surrey, England | ||||||

| Spouse | |||||||

| Alma mater | Royal Military College, Sandhurst | ||||||

| Profession | Soldier, explorer, colonial administrator | ||||||

| Military service | |||||||

| Allegiance | |||||||

| Branch/service | |||||||

| Years of service | 1878–1919 | ||||||

| Rank | Major | ||||||

| Battles/wars | Second Anglo-Afghan War Mahdist War Third Anglo-Burmese War Karonga War World War I | ||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 盧吉 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 卢吉 | ||||||

| |||||||

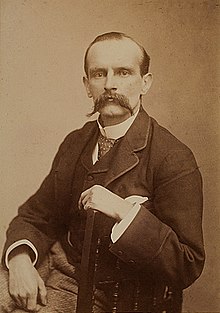

Frederick John Dealtry Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard

Early life and education

Lugard was born in

Military career

Lugard was commissioned into the 9th Foot (East Norfolk Regiment) in 1878 and joined the second battalion in India; he served in the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880), the Sudan campaign (1884–1885) and the Third Anglo-Burmese War (November 1885) and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in 1887.[2] After this promising start, his career was derailed when he fell in love with a twice married British divorcee he met in India; learning she had been injured in an accident, he abandoned his post in Burma to join her in Lucknow, then followed her to England. When she rejected him, Lugard decided to make a fresh start in Africa.[3]

Karonga War

Around 1880, a group of

Relations between the two groups deteriorated, partly because of the company's delays or unwillingness to provide guns, ammunition and other trade goods, and also because the Swahili traders turned more to slaving, attacking communities that the company had promised to protect, and hostilities broke out in mid-1887. The series of intermittent armed clashes that took place up to mid-1889 is known as the Karonga War, or sometimes the Arab War.[6]

The African Lakes Company depot at Karonga was evacuated at the end of the year but in May 1888, Captain Lugard, persuaded by the British Consul at Mozambique, arrived to lead an expedition against Mlozi, sponsored by the African Lakes Company but without official support from the British government.[7]

Lugard's first expedition of May to June 1888 attacked the Swahili stockades with limited success and, in the course of one attack, Lugard was wounded and withdrew south.[8][9] Lugard's second expedition in December 1888 to March 1889 was larger and included a 7-pounder gun, which, however, failed to breach the stockade walls. Following this second failure, Lugard left the Lake Malawi region for Britain in April 1889.[10][11]

Exploration of East Africa

After leaving Nyasaland in April 1889, Lugard accepted a position with the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) and arrived in Mombasa on the coast of east Africa that December.[12] A year earlier in 1888, the IBEAC had been granted a royal charter by Queen Victoria to colonise the 'British sphere of influence' between Zanzibar and Uganda[13] and were keen to open a trading route between Lake Victoria in Uganda and the coastal port of Mombasa. Their first interior trading post was established at Machakos 240 miles in from the coast. But the established traditional route to Machakos was a treacherous journey through the large Taru Desert —93 miles of scorching dust bowl.[citation needed]

Lugard's first mission was to determine the feasibility of a route from Mombasa to Machakos that would bypass the Taru Desert.

On 6 August 1890, Lugard began his caravan expedition to Uganda, accompanied by five other Europeans - George Wilson, Fenwick De Winton (son of Francis de Winton - Lugard's other chief), William Grant and Archibald Brown.

Departing from Mombasa towards

En route, Lugard was instructed to enter into treaties with local tribes and build forts in order to secure safe passage for future IBEAC expeditions.[18] The IBEAC employed official treaty documents that were signed by their administrator and the local leaders but Lugard preferred the more equitable blood brotherhood ceremony[12] and entered into several brotherhood partnerships with leaders who inhabited the areas between Mombasa and Uganda. One of his famed blood partnerships was sealed in October 1890 during his journey to Uganda when he stopped at Dagoretti in Kikuyu territory and entered into an alliance with Waiyaki Wa Hinga.[19]

Lugard was Military Administrator of Uganda from 26 December 1890 to May 1892. While administering Uganda, he journeyed round the

When Lugard returned to England in 1892, he successfully dissuaded Prime Minister William Gladstone from allowing the IBEAC to abandon Uganda.[20]

Early colonial service

In 1894, Lugard was dispatched by the

After relinquishing command of the West African Frontier Force, Lugard was appointed

In 1903, British control over the whole

Lugard was knighted in the 1901 New Year Honours for his service in Nigeria.[22]

Lugard restored peace and order, and suppressed

Governor of Hong Kong

About a year after he resigned as High Commissioner of the

Lugard's chief interest was education and he was largely remembered for his efforts to the founding of the

Governor of Nigeria

In 1912, Lugard returned to Nigeria as Governor of the two

Lugard, assisted by his indefatigable wife,

Funding of the colony of Nigeria in the development of state's infrastructure such as harbours, railways and hospitals in Southern Nigeria came from revenue generated by taxes on imported alcohol. In Northern Nigeria, the revenue that allowed state development projects was less because the taxes was absent and thus funding of projects was covered from revenue generated in the south.[citation needed]

The

When the British Government decided to raise a local militia to protect the western frontier of the

Lugard's greatest contribution to the making of modern Nigeria was the successful amalgamation of the North and South in 1914. and a common civil service, he introduced all the necessities needed for infrastructure in a modern state.

More importantly, he laid the foundations of continuous legislative assemblies in Nigeria by establishing the Nigerian council in 1914.

In spite of his contributions, Lugard's work was not without faults. "He aimed at creating in Nigeria one administrative unit but he did not intend to create a Nigerian nation".[41] Instead, his policy of isolating the North from the South, a policy which his successors maintained had a hand in the present disunity of Nigeria till today. An example is the exclusion of the North from the Legislative Council until 1947. "Thus, it can be said that Lugard sowed the seeds of separatist tendency which has still plagued Nigerian unity".[42] Lugard was also partly responsible for the backwardness in the education and other social services of the Northerners And this is the reason for the South's advance in education over the North. To sum it up, Lugard's attitude to Nigeria implied that he did not envisage self-government for Nigeria. He planned for perpetual

Regarding the future of British colonialism in Africa, he stated, "For two or three generations we can show the negro what we are, then we shall be asked to go away. Then we shall leave the land to those it belongs to with a feeling that they have better business friends in us than in other white men."[44]

The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa

Lugard's The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa was published in 1922 and discussed indirect rule in colonial Africa.[45] He argued that administration of Africa could simultaneously promote the well-being of the inhabitants and develop the resources of the continent for the benefit of mankind.[45] According to Lugard, there were three principles of colonial administration: decentralization (granting power to local district officers in colonies), continuity (extensive record-keeping so that successors would build upon the policies of predecessors), and cooperation (building local support for the colonial government).[46] He defended British colonial practices, in particular the system of indirect rule that he introduced in Nigeria.[45] The task of the British, he wrote, was ‘to promote the commercial and industrial progress of Africa without too careful a scrutiny of the material gains to ourselves’.[47]

In this work, Lugard outlined the reasons and methods that he recommended for the colonisation of Africa. Some of his justifications for establishing colonial rule included spreading Christianity and ending barbaric practises by African such as human sacrifice. He also saw state-sponsored colonisation as a way to protect missionaries, local chiefs and local people from each other, as well as from foreign powers. For Lugard, it was also vital that Britain gain control of unclaimed areas before Germany, Portugal or France claimed the land and its resources for themselves. He realised that there were vast profits to be made through the export of resources such as rubber, and through taxation of native populations as well as importers and exporters (the British taxpayer continually made a loss from the colonies in this period). In addition, these resources and inexpensive native labour (slavery having been abolished by Britain in 1833) would provide vital fuel for the industrial revolution in resource-depleted Britain, as well as monies for public works projects. Finally, Lugard reasoned that colonisation had become a fad and that, in order to remain a global power, Britain would need to hold colonies to avoid appearing weak.

William Rappard was influenced by Lugard's book.[45] He sought to get Lugard appointed to the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations.[45]

League of Nations and Abolitionist activism

Between 1922 and 1936, Lugard was the British representative on the League of Nations' Permanent Mandates Commission. Lugard saw imperial administration in moral terms and advocated for humane principles of colonial rule.[45] He saw the role of the Permanent Mandates Commission as involving standard-setting and oversight, whereas actual administration should be left to national powers.[45]

Lugard supported General George Spafford Richardson's repressive rule of Western Samoa. Lugard criticized European settlers and Samoans who engaged in "interracial mobilization."[48] Lugard played a key role in drafting a Commission report that exonerated Richardson's governance of Western Samoa and placed the blame of the Western Samoa unrest on the anti-colonial activist Olaf Frederick Nelson.[48]

During this period he served first on the Temporary Slavery Commission and was involved in organising the 1926 Slavery Convention. He had submitted a proposal for the convention to the British government. Although they were initially alarmed by it, the British government backed the proposal (after subjecting it to considerable redrafting) and it was eventually enacted.[49] Lugard served on the International Labour Organization's Committee of Experts on Native Labour from 1925 to 1941.[50]

Views

Lugard pushed for native rule in African colonies. He reasoned that black Africans were very different from white Europeans, although he did speculate on the admixture of

Olúfẹmi Táíwò argues that Lugard blocked Africans who had been educated in Europe from playing an active role in the development of Colonial Nigeria; he distrusted white "intellectuals" as much as black ones, believing that the principles they were taught in the universities were often wrong. Lugard preferred to advance prominent Hausa and Fulani leaders from traditional structures.[52]

Lugard was an advocate for European paternalist governance over Africans. He described Africans as holding "the position of a late-born child in the family of nations, and must as yet be schooled in the discipline of the nursery."[53]

Honours

Lugard was appointed a Companion of the

The

A bronze bust of Lugard, created by Pilkington Jackson in 1960, is held in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Lugard Road on Victoria Peak in Hong Kong, China is named after him.

Personal life

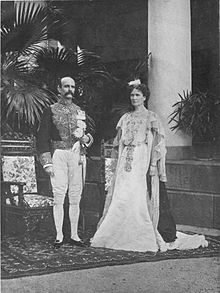

Lugard married, on 10 June 1902,

Published works

- In 1893, Lugard published The Rise of our East African Empire, which was partially an autobiography. He was also the author of various valuable reports on Northern Nigeria issued by the Colonial Office.

- The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa, 1922.

See also

- Indirect rule

- Richmond Palmer

- Frank Lugard Brayne

- George Wilson (Chief Colonial Secretary of Uganda)

References

- ^ The New Extinct Peerage 1884-1971: Containing Extinct, Abeyant, Dormant and Suspended Peerages With Genealogies and Arms, L. G. Pine, Heraldry Today, 1972, p. 185

- ^ "No. 25761". The London Gazette. 25 November 1887. p. 6374.

- ISBN 978-0241004524.

- ^ O. J. M. Kalinga, (1980), The Karonga War: Commercial Rivalry and Politics of Survival, Journal of African History, Vol. 21, p. 209

- ISBN 978-0-521-21444-5

- ISBN 978-0-521-21444-5

- ISBN 0-415-41063-0

- ISBN 0-415-41063-0

- ^ P. T. Terry, (1965). The Arab War on Lake Nyasa 1887–1895, The Nyasaland Journal, Vol. 18, No. 1 pp. 74–5(Part I)

- ISBN 0-415-41063-0

- ^ P. T. Terry, (1965). The Arab War on Lake Nyasa 1887–1895 P. T. Terry, (1965). The Arab War on Lake Nyasa 1887–1895 Part II, The Nyasaland Journal, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 31–33

- ^ OCLC 968732897.

- ^ "The Imperial British East Africa Company – IBEAC". Softkenya.com. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ISBN 9781784972714.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911, p. 116.

- ^ The London Quarterly and Holborn Review. E.C. Barton. 1894. p. 330.

- ISBN 9780889205482.

- ISBN 9781857252064.

- ISBN 9781317514817.

- ISBN 978-1-4438-3035-5.

- ^ "The Transfer of Nigeria to the Crown". The Times. No. 36060. London. 8 February 1900. p. 7.

- ^ a b "No. 27261". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 December 1900. p. 1.

- OCLC 16490698.

- ^ "No. 28024". The London Gazette. 24 May 1907. p. 3589.

- ^ Vines, Stephen (29 June 1997). "How Britain lost chance to keep its last major colony". The Independent. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Carroll JM (2007). A Concise History of Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p.85.

- ISSN 0737-8947.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-0981-1.

- OCLC 69638.

- OCLC 613013836.

- ISBN 978-0-19-957916-7.

- ISBN 9781512815306, retrieved 5 January 2022

- ISBN 9781315032757

- ISBN 9780520327108, retrieved 5 January 2022

- ISBN 9781137122575

- OCLC 19060960.

- OCLC 5727823.

- ISSN 1595-0611.

- OCLC 16598969.

- OCLC 504865.

- ^ Lugard, Frederick. History of West Africa, Book Two, 1800-Present Day. Jurong, Singapore: K.B.C Onwubiko. pp. 270–272.

- ^ a b Lugard, Frederick. History of West Africa, Book Two, 1800-Present Day. Jurong, Singapore: K.B.C Onwubiko. p. 272.

- ISBN 9780226470689, retrieved 5 January 2022

- ^ "Recolonisation Issues". London Review of Books. 23 (2). 2001. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-957048-5.

- ^ Myerson, Roger B. (10 November 2022). "Stabilization Lessons from the British Empire". Texas National Security Review.

- ^ Johnson, Paul (1999) Modern Times pp.156

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-957048-5.

- ^ Miers, Suzanne. ""Freedom is a good thing but it means a dearth of slaves": Twentieth Century Solutions to the Abolition of Slavery" (PDF). Yale University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- OL 25434623M

- ^ The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa p76

- ^ 'Reading the Colonizer's Mind: Lord Lugard and the Philosophical Foundations of British Colonialism' by Olufemi Taiwo in Racism and Philosophy edited by Susan E. Babbitt and Sue Campbell, Cornell University Press, 1999

- ISBN 978-0-521-44783-6.

- ^ "No. 26639". The London Gazette. 2 July 1895. p. 3740.

- ^ "No. 31712". The London Gazette (Supplement). 30 December 1919. p. 1.

- ^ "No. 33369". The London Gazette. 23 March 1928. p. 2129.

- ^ "Royal Geographical Society". The Times. No. 36716. London. 15 March 1902. p. 12.

- ^ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36792. London. 12 June 1902. p. 12.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lugard, Sir Frederick John Dealtry". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 115–116.

- Biography, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Further reading

- Lord Lugard, Frederick D. (1965). The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa. Fifth Edition. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Middleton, Dorothy (1959). Lugard in Africa. London: Robert Hale, Ltd.

- Miller, Charles (1971). The Lunatic Express, An Entertainment in Imperialism.

- Meyer, Karl E. and Shareen Blair Brysac. Kingmakers: The Invention of the Modern Middle East (2009) pp 59–93.

- Pederson, Susan (2015). The Guardians: the League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perham, Marjery (July 1945). "Lord Lugard: A General Appreciation". S2CID 147554864.

- Perham, Margery (1956). Lugard. Volume 1: The Years of Adventure 1858–1898. London: Collins.

- Perham, Margery (1960). Lugard. Volume 2: The Years of Authority 1898–1945. London: Collins.

- Perham, Margery, ed. (1959). The Diaries of Lord Lugard (3 Vols.). London: Faber & Faber.

- Taiwo, Alufemi (1999). "Reading the Colonizer's Mind: Lord Lugard and the Philosophical Foundations of British Colonialism". In Babbitt, Susan E; Campbell, Sue (eds.). Racism and Philosophy. Cornell University Press.