French India

French Settlements in India Établissements français dans l'Inde (French) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1664–1954 | |||||||||||

| Government | Colonial administration | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1668–1673 | François Caron (first) [2] | ||||||||||

• 1954 | Georges Escaragueil[3] | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Representative Assembly of French India | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• First French East India Company Commissioner of Surat | 1664 | ||||||||||

• De facto transfer | 1 November 1954 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1936 | 510 km2 (200 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1936 | 298,861 | ||||||||||

| Currency | French Indian Rupee | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||||

| Colonial India | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

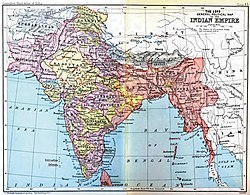

French India, formally the Établissements français dans l'Inde[a] (English: French Settlements in India), was a French colony comprising five geographically separated enclaves on the Indian subcontinent that had initially been factories of the French East India Company. They were de facto incorporated into the Republic of India in 1950 and 1954. The enclaves were Pondichéry, Karikal, Yanam on the Coromandel Coast, Mahé on the Malabar Coast and Chandernagor in Bengal. The French also possessed several loges ('lodges', tiny subsidiary trading stations) inside other towns, but after 1816, the British denied all French claims to these, which were not reoccupied.

By 1950, the total area measured 510 km2 (200 sq mi), of which 293 km2 (113 sq mi) belonged to the territory of Pondichéry. In 1936, the population of the colony totalled 298,851 inhabitants, of which 63% (187,870) lived in the territory of Pondichéry.[4]

Background

France was the last of the major European maritime powers of the 17th century to enter the East India trade. Six decades after the foundation of the English and Dutch East India companies (in 1600 and 1602 respectively), and at a time when both companies were multiplying factories (trading posts) on the shores of India, the French still did not have a viable trading company or a single permanent establishment in the East.

Seeking to explain France's late entrance in the East India trade, historians cite geopolitical circumstances such as the inland position of the French capital, France's numerous internal customs barriers, and parochial perspectives of merchants on France's Atlantic coast, who had little appetite for the large-scale investment required to develop a viable trading enterprise with the distant East Indies.[5][6]

History

Initial marine voyages to India (16th century)

The first French commercial venture to India is believed to have taken place in the first half of the 16th century, in the reign of King Francis I, when two ships were fitted out by some merchants of Rouen to trade in eastern seas; they sailed from Le Havre and were never heard of again. In 1604, a company was granted letters patent by King Henry IV, but the project failed. Fresh letters patent were issued in 1615, and two ships went to India, only one returning.[7]

La Compagnie française des Indes orientales (French East India Company) was formed under the auspices of Cardinal Richelieu (1642) and reconstructed under Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1664), sending an expedition to Madagascar.[8][9][7]

First factory in India (1668)

In 1667, the French India Company sent out another expedition, under the command of

French expansion in India (1669-1672)

In 1669, Marcara succeeded in establishing another French factory at

Establishment of colony at Pondichéry (1673)

On 4 February 1673, Bellanger de l'Espinay, a French officer, took up residence in the Danish Lodge in Pondichéry, thereby commencing the French administration of Pondichéry. In 1674,

Establishment of colonies at Yanon (1723) and Karaikal (1739)

From their arrival until 1741, the objectives of the French, like those of the British, were purely commercial. During this period, the French East India Company peacefully acquired

Ambition of establishment of French territorial empire in India and defeat (1741–1754)

Soon after his arrival in 1741, the most famous governor of French India,

After a defeat and failed peace talks, Dupleix was summarily dismissed and recalled to France in 1754.

French vs British intrigues (1754–1871)

In spite of a treaty between the British and French agreeing not to interfere in regional Indian affairs, their colonial intrigues continued. The French expanded their influence at the court of the

Subsequently, France sent

In 1765, Pondichéry was returned to France in accordance with

In 1816, after the conclusion of the

By a decree of 25 January 1871, French India was to have an elective general council (conseil général) and elective local councils (conseil local). The results of this measure were not very satisfactory, and the qualifications for and the classes of the franchise were modified. The governor resided at Pondichéry and was assisted by a council. There were two

Independence movement (18th–20th century) and merger with India (1954)

The

The myth of "our immense empire in India"

From the mid-19th century onward there developed in France the belief that the five tiny settlements recovered from Britain after the Napoleonic Wars were remnants of the "immense empire" acquired by Dupleix in the 18th century. "Our immense empire of India was reduced to five settlements" wrote French economist and colonial expansion promoter Pierre Paul Leroy-Beaulieu in 1886.[11] An atlas published in the 1930s described those five settlements as "remnants of the great colonial empire that France had created in India in the 18th century".[12] More recently, a historian of French India post-1816 described them as "debris of an empire" and the "last remnants of an immense empire forever lost".[13] However, France never held much more than the five settlements recovered in 1816. The historian of French India and archivist Alfred Martineau, who was also governor of French India, pointed out that the authority granted to Dupleix over the Carnatic in 1750 should not be construed as a transfer of sovereignty, as wrote most historians, given that Dupleix only became so to speak the lieutenant of the Indian subah, who could withdraw his power delegation at his convenience.[14] Philippe Haudrère, historian of the French East India Company, also wrote that Dupleix controlled those territories through a complex system of treaties and alliance, a system almost feudal in nature, but that those territories were neither annexed nor transformed into protectorates.[15]