Frog

| Frogs | |

|---|---|

| |

| Various types of frog | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Clade: | Salientia |

| Order: | Anura Duméril, 1806 (as Anoures) |

| Subgroups | |

|

See text | |

| |

| Native distribution of frogs (in green) | |

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely

An adult frog has a stout body, protruding eyes, anteriorly-attached tongue, limbs folded underneath, and no tail (the tail of tailed frogs is an extension of the male cloaca). Frogs have glandular skin, with secretions ranging from distasteful to toxic. Their skin varies in colour from well-camouflaged dappled brown, grey and green to vivid patterns of bright red or yellow and black to show toxicity and ward off predators. Adult frogs live in fresh water and on dry land; some species are adapted for living underground or in trees.

Frogs typically lay their

Frogs are valued as food by humans and also have many cultural roles in literature, symbolism and religion. They are also seen as

Etymology and taxonomy

The use of the common names frog and

Etymology

The origin of the order name Anura—and its original spelling Anoures—is the Ancient Greek "alpha privative" prefix ἀν- (an- from ἀ- before a vowel) 'without',[6] and οὐρά (ourá) 'animal tail'.[7] meaning "tailless". It refers to the tailless character of these amphibians.[8][9][10]

The origins of the word frog are uncertain and debated.[11] The word is first attested in Old English as frogga, but the usual Old English word for the frog was frosc (with variants such as frox and forsc), and it is agreed that the word frog is somehow related to this. Old English frosc remained in dialectal use in English as frosh and frosk into the nineteenth century,[12] and is paralleled widely in other Germanic languages, with examples in the modern languages including German Frosch, Norwegian frosk, Icelandic froskur, and Dutch (kik)vors.[11] These words allow reconstruction of a Common Germanic ancestor *froskaz.[13] The third edition of the Oxford English Dictionary finds that the etymology of *froskaz is uncertain, but agrees with arguments that it could plausibly derive from a Proto-Indo-European base along the lines of *preu, meaning 'jump'.[11]

How Old English frosc gave rise to frogga is, however, uncertain, as the development does not involve a regular sound-change. Instead, it seems that there was a trend in Old English to coin nicknames for animals ending in -g, with examples—themselves all of uncertain etymology—including dog, hog, pig, stag, and (ear)wig. Frog appears to have been adapted from frosc as part of this trend.[11]

Meanwhile, the word toad, first attested as Old English tādige, is unique to English and is likewise of uncertain etymology.[14] It is the basis for the word tadpole, first attested as Middle English taddepol, apparently meaning 'toad-head'.[15]

Taxonomy

About 88% of

The Anura include all modern frogs and any

Frogs and toads are broadly classified into three suborders:

Some species of anurans hybridize readily. For instance, the edible frog (Pelophylax esculentus) is a hybrid between the pool frog (P. lessonae) and the marsh frog (P. ridibundus).[22] The fire-bellied toads Bombina bombina and B. variegata are similar in forming hybrids. These are less fertile than their parents, giving rise to a hybrid zone where the hybrids are prevalent.[23]

Evolution

The origins and evolutionary relationships between the three main groups of amphibians are hotly debated. A

In 2008,

On the basis of fossil evidence, the earliest known "true frogs" that fall into the anuran lineage proper all lived in the early

According to genetic studies, the families

Frog fossils have been found on all of the Earth's continents.

Phylogeny

A cladogram showing the relationships of the different families of frogs in the clade Anura can be seen in the table below. This diagram, in the form of a tree, shows how each frog family is related to other families, with each node representing a point of common ancestry. It is based on Frost et al. (2006),[43] Heinicke et al. (2009)[44] and Pyron and Wiens (2011).[45]

| Anura |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Morphology and physiology

Frogs have no tail, except as larvae, and most have long hind legs, elongated ankle bones, webbed toes, no claws, large eyes, and a smooth or warty skin. They have short vertebral columns, with no more than 10 free vertebrae and fused tailbones (urostyle or coccyx).[46] Frogs range in size from Paedophryne amauensis of Papua New Guinea that is 7.7 mm (0.30 in) in snout–to–vent length[47] to the up to 32 cm (13 in) and 3.25 kg (7.2 lb) goliath frog (Conraua goliath) of central Africa.[48] There are prehistoric, extinct species that reached even larger sizes.[49]

Feet and legs

The structure of the feet and legs varies greatly among frog species, depending in part on whether they live primarily on the ground, in water, in trees, or in burrows. Adult anurans have four fingers on the hands and five toes on the feet,

(Rana temporaria)

The muscular system has been similarly modified. The hind limbs of ancestral frogs presumably contained pairs of muscles which would act in opposition (one muscle to flex the knee, a different muscle to extend it), as is seen in most other limbed animals. However, in modern frogs, almost all muscles have been modified to contribute to the action of jumping, with only a few small muscles remaining to bring the limb back to the starting position and maintain posture. The muscles have also been greatly enlarged, with the main leg muscles accounting for over 17% of the total mass of frogs.[52]

Many frogs have webbed feet and the degree of webbing is directly proportional to the amount of time the species spends in the water.

In many arboreal frogs, a small "intercalary structure" on each toe increases the surface area touching the substrate. Furthermore, many arboreal frogs have hip joints that allow both hopping and walking. Some frogs that live high in trees even possess an elaborate degree of webbing between their toes. This allows the frogs to "parachute" or make a controlled glide from one position in the canopy to another.[56]

Ground-dwelling frogs generally lack the adaptations of aquatic and arboreal frogs. Most have smaller toe pads, if any, and little webbing. Some burrowing frogs such as

Sometimes during the tadpole stage, one of the developing rear legs is eaten by a predator such as a

Skin

A frog's skin is protective, has a respiratory function, can absorb water, and helps control body temperature. It has many glands, particularly on the head and back, which often exude distasteful and toxic substances (granular glands). The secretion is often sticky and helps keep the skin moist, protects against the entry of moulds and bacteria, and makes the animal slippery and more able to escape from predators.[59] The skin is shed every few weeks. It usually splits down the middle of the back and across the belly, and the frog pulls its arms and legs free. The sloughed skin is then worked towards the head where it is quickly eaten.[60]

Being cold-blooded, frogs have to adopt suitable behaviour patterns to regulate their temperature. To warm up, they can move into the sun or onto a warm surface; if they overheat, they can move into the shade or adopt a stance that exposes the minimum area of skin to the air. This posture is also used to prevent water loss and involves the frog squatting close to the substrate with its hands and feet tucked under its chin and body.

Many frogs are able to absorb water and oxygen directly through the skin, especially around the pelvic area, but the permeability of a frog's skin can also result in water loss. Glands located all over the body exude mucus which helps keep the skin moist and reduces evaporation. Some glands on the hands and chest of males are specialized to produce sticky secretions to aid in

Some species have bony plates embedded in the skin, a trait that appears to have evolved independently several times.[65] In certain other species, the skin at the top of the head is compacted and the connective tissue of the dermis is co-ossified with the bones of the skull (exostosis).[66][67]

Respiration and circulation

Like other amphibians, oxygen can pass through their highly permeable skins. This unique feature allows them to remain in places without access to the air, respiring through their skins. Ribs are generally absent, so the lungs are filled by buccal pumping and a frog deprived of its lungs can maintain its body functions without them.[68] The fully aquatic Bornean flat-headed frog (Barbourula kalimantanensis) is the first frog known to lack lungs entirely.[71]

Frogs have three-chambered

Some species of frog have adaptations that allow them to survive in oxygen deficient water. The

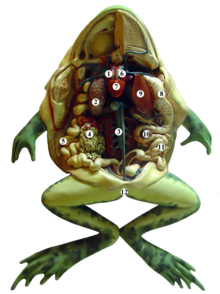

Digestion and excretion

Frogs have maxillary teeth along their upper jaw which are used to hold food before it is swallowed. These teeth are very weak, and cannot be used to chew or catch and harm agile prey. Instead, the frog uses its sticky, cleft tongue to catch insects and other small moving prey. The tongue normally lies coiled in the mouth, free at the back and attached to the mandible at the front. It can be shot out and retracted at great speed.[53] In amphibians there are salvary glands on the tongue, which in frogs produce what is called a two-phase viscoelastic fluid. When exposed to pressure, like when the tongue is wrapping around a prey, it becomes runny and covers the prey's body. As the pressure drops, it returns to a thick and elastic state, which gives the tongue an extra grip.[74] Some frogs have no tongue and just stuff food into their mouths with their hands.[53] The African bullfrog (Pyxicephalus), which preys on relatively large animals such as mice and other frogs, has cone shaped bony projections called odontoid processes at the front of the lower jaw which function like teeth.[16] The eyes assist in the swallowing of food as they can be retracted through holes in the skull and help push food down the throat.[53][75]

The food then moves through the oesophagus into the stomach where digestive enzymes are added and it is churned up. It then proceeds to the small intestine (duodenum and ileum) where most digestion occurs. Pancreatic juice from the pancreas, and bile, produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder, are secreted into the small intestine, where the fluids digest the food and the nutrients are absorbed. The food residue passes into the large intestine where excess water is removed and the wastes are passed out through the cloaca.[76]

Although adapted to terrestrial life, frogs resemble freshwater fish in their inability to conserve body water effectively. When they are on land, much water is lost by evaporation from the skin. The excretory system is similar to that of mammals and there are two

Reproductive system

In the male frog, the two

When frogs mate, the male climbs on the back of the female and wraps his fore limbs round her body, either behind the front legs or just in front of the hind legs. This position is called

Nervous system

Frogs have a highly developed nervous system that consists of a brain, spinal cord and nerves. Many parts of frog brains correspond with those of humans. It consists of two olfactory lobes, two cerebral hemispheres, a pineal body, two optic lobes, a cerebellum and a medulla oblongata. Muscular coordination and posture are controlled by the

Sight

The eyes of most frogs are located on either side of the head near the top and project outwards as hemispherical bulges. They provide binocular vision over a field of 100° to the front and a total visual field of almost 360°.[82] They may be the only part of an otherwise submerged frog to protrude from the water. Each eye has closable upper and lower lids and a nictitating membrane which provides further protection, especially when the frog is swimming.[83] Members of the aquatic family Pipidae have the eyes located at the top of the head, a position better suited for detecting prey in the water above.[82] The irises come in a range of colours and the pupils in a range of shapes. The common toad (Bufo bufo) has golden irises and horizontal slit-like pupils, the red-eyed tree frog (Agalychnis callidryas) has vertical slit pupils, the poison dart frog has dark irises, the fire-bellied toad (Bombina spp.) has triangular pupils and the tomato frog (Dyscophus spp.) has circular ones. The irises of the southern toad (Anaxyrus terrestris) are patterned so as to blend in with the surrounding camouflaged skin.[83]

The distant vision of a frog is better than its near vision. Calling frogs will quickly become silent when they see an intruder or even a moving shadow but the closer an object is, the less well it is seen.[83] When a frog shoots out its tongue to catch an insect it is reacting to a small moving object that it cannot see well and must line it up precisely beforehand because it shuts its eyes as the tongue is extended.[53] Although it was formerly debated,[84] more recent research has shown that frogs can see in colour, even in very low light.[85]

Hearing

Frogs can hear both in the air and below water. They do not have

Call

The call or croak of a frog is unique to its species. Frogs create this sound by passing air through the

The main function of calling is for male frogs to attract mates. Males may call individually or there may be a chorus of sound where numerous males have converged on breeding sites. In many frog species, such as the

A different call is emitted by a male frog or unreceptive female when mounted by another male. This is a distinct chirruping sound and is accompanied by a vibration of the body.[94] Tree frogs and some non-aquatic species have a rain call that they make on the basis of humidity cues prior to a shower.[94] Many species also have a territorial call that is used to drive away other males. All of these calls are emitted with the mouth of the frog closed.[94] A distress call, emitted by some frogs when they are in danger, is produced with the mouth open resulting in a higher-pitched call. It is typically used when the frog has been grabbed by a predator and may serve to distract or disorient the attacker so that it releases the frog.[94]

Many species of frog have deep calls. The croak of the

Torpor

During extreme conditions, some frogs enter a state of torpor and remain inactive for months. In colder regions, many species of frog hibernate in winter. Those that live on land such as the American toad (Bufo americanus) dig a burrow and make a hibernaculum in which to lie dormant. Others, less proficient at digging, find a crevice or bury themselves in dead leaves. Aquatic species such as the American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) normally sink to the bottom of the pond where they lie, semi-immersed in mud but still able to access the oxygen dissolved in the water. Their metabolism slows down and they live on their energy reserves. Some frogs such as the wood frog, moor frog, or spring peeper can even survive being frozen. Ice crystals form under the skin and in the body cavity but the essential organs are protected from freezing by a high concentration of glucose. An apparently lifeless, frozen frog can resume respiration and its heartbeat can restart when conditions warm up.[99]

At the other extreme, the

Locomotion

Different species of frog use a number of methods of moving around including jumping, running, walking, swimming, burrowing, climbing and gliding.

- Jumping

Frogs are generally recognized as exceptional jumpers and, relative to their size, the best jumpers of all vertebrates.[103] The striped rocket frog, Litoria nasuta, can leap over two metres (6+1⁄2 feet), a distance that is more than fifty times its body length of 55 mm (2+1⁄4 in).[104] There are tremendous differences between species in jumping capability. Within a species, jump distance increases with increasing size, but relative jumping distance (body-lengths jumped) decreases. The Indian skipper frog (Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis) has the ability to leap out of the water from a position floating on the surface.[105] The tiny northern cricket frog (Acris crepitans) can "skitter" across the surface of a pond with a series of short rapid jumps.[106]

Slow-motion photography shows that the muscles have passive flexibility. They are first stretched while the frog is still in the crouched position, then they are contracted before being stretched again to launch the frog into the air. The fore legs are folded against the chest and the hind legs remain in the extended, streamlined position for the duration of the jump.[52] In some extremely capable jumpers, such as the Cuban tree frog (Osteopilus septentrionalis) and the northern leopard frog (Rana pipiens), the peak power exerted during a jump can exceed that which the muscle is theoretically capable of producing. When the muscles contract, the energy is first transferred into the stretched tendon which is wrapped around the ankle bone. Then the muscles stretch again at the same time as the tendon releases its energy like a catapult to produce a powerful acceleration beyond the limits of muscle-powered acceleration.[107] A similar mechanism has been documented in locusts and grasshoppers.[108]

Early hatching of froglets can have negative effects on frog jumping performance and overall locomotion.[109] The hindlimbs are unable to completely form, which results in them being shorter and much weaker relative to a normal hatching froglet.[109] Early hatching froglets may tend to depend on other forms of locomotion more often, such as swimming and walking.[109]

- Walking and running

Frogs in the families Bufonidae,

The

- Swimming

Frogs that live in or visit water have adaptations that improve their swimming abilities. The hind limbs are heavily muscled and strong. The webbing between the toes of the hind feet increases the area of the foot and helps propel the frog powerfully through the water. Members of the family Pipidae are wholly aquatic and show the most marked specialization. They have inflexible vertebral columns, flattened, streamlined bodies, lateral line systems, and powerful hind limbs with large webbed feet.[115] Tadpoles mostly have large tail fins which provide thrust when the tail is moved from side to side.[116]

- Burrowing

Some frogs have become adapted for burrowing and a life underground. They tend to have rounded bodies, short limbs, small heads with bulging eyes, and hind feet adapted for excavation. An extreme example of this is the purple frog (Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis) from southern India which feeds on termites and spends almost its whole life underground. It emerges briefly during the monsoon to mate and breed in temporary pools. It has a tiny head with a pointed snout and a plump, rounded body. Because of this fossorial existence, it was first described in 2003, being new to the scientific community at that time, although previously known to local people.[117]

The spadefoot toads of North America are also adapted to underground life. The

The burrowing frogs of Australia have a rather different lifestyle. The western spotted frog (Heleioporus albopunctatus) digs a burrow beside a river or in the bed of an ephemeral stream and regularly emerges to forage. Mating takes place and eggs are laid in a foam nest inside the burrow. The eggs partially develop there, but do not hatch until they are submerged following heavy rainfall. The tadpoles then swim out into the open water and rapidly complete their development.[120] Madagascan burrowing frogs are less fossorial and mostly bury themselves in leaf litter. One of these, the green burrowing frog (Scaphiophryne marmorata), has a flattened head with a short snout and well-developed metatarsal tubercles on its hind feet to help with excavation. It also has greatly enlarged terminal discs on its fore feet that help it to clamber around in bushes.[121] It breeds in temporary pools that form after rains.[122]

- Climbing

Tree frogs live high in the

- Gliding

During the evolutionary history of frogs, several different groups have independently taken to the air.

Life history

(Rana clamitans)

Reproduction

Two main types of reproduction occur in frogs, prolonged breeding and explosive breeding. In the former, adopted by the majority of species, adult frogs at certain times of year assemble at a pond, lake or stream to breed. Many frogs return to the bodies of water in which they developed as larvae. This often results in annual migrations involving thousands of individuals. In explosive breeders, mature adult frogs arrive at breeding sites in response to certain trigger factors such as rainfall occurring in an arid area. In these frogs, mating and spawning take place promptly and the speed of larval growth is rapid in order to make use of the ephemeral pools before they dry up.[129]

Among prolonged breeders, males usually arrive at the breeding site first and remain there for some time whereas females tend to arrive later and depart soon after they have spawned. This means that males outnumber females at the water's edge and defend territories from which they expel other males. They advertise their presence by calling, often alternating their croaks with neighbouring frogs. Larger, stronger males tend to have deeper calls and maintain higher quality territories. Females select their mates at least partly on the basis of the depth of their voice.[130] In some species there are satellite males who have no territory and do not call. They may intercept females that are approaching a calling male or take over a vacated territory. Calling is an energy-sapping activity. Sometimes the two roles are reversed and a calling male gives up its territory and becomes a satellite.[129]

In explosive breeders, the first male that finds a suitable breeding location, such as a temporary pool, calls loudly and other frogs of both sexes converge on the pool. Explosive breeders tend to call in unison creating a chorus that can be heard from far away. The spadefoot toads (

At the breeding site, the male mounts the female and grips her tightly round the body. Typically,

Life cycle

Eggs / frogspawn

Frogs may lay their in eggs as clumps, surface films, strings, or individually. Around half of species deposit eggs in water, others lay eggs in vegetation, on the ground or in excavations.

In certain species, such as the

Direct development, where eggs hatch into juveniles like small adults, is also known in many frogs, for example, Ischnocnema henselii,[145] Eleutherodactylus coqui,[146] and Raorchestes ochlandrae and Raorchestes chalazodes.[147]

Tadpoles

The larvae that emerge from the eggs, known as tadpoles (or occasionally polliwogs). Tadpoles lack eyelids and limbs, and have cartilaginous skeletons, gills for respiration (external gills at first, internal gills later), and tails they use for swimming.[116] As a general rule, free-living larvae are fully aquatic, but at least one species (Nannophrys ceylonensis) has semiterrestrial tadpoles which live among wet rocks.[148][149]

From early in its development, a gill pouch covers the tadpole's gills and front legs. The lungs soon start to develop and are used as an accessory breathing organ. Some species go through metamorphosis while still inside the egg and hatch directly into small frogs. Tadpoles lack true teeth, but the jaws in most species have two elongated, parallel rows of small,

Tadpoles are typically

Tadpoles are highly vulnerable to being eaten by fish,

Metamorphosis

At the end of the tadpole stage, a frog undergoes metamorphosis in which its body makes a sudden transition into the adult form. This metamorphosis typically lasts only 24 hours, and is initiated by production of the

Adults

Adult frogs may live in or near water, but few are fully aquatic.

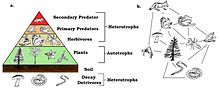

Frogs are primary predators and an important part of the food web. Being cold-blooded, they make efficient use of the food they eat with little energy being used for metabolic processes, while the rest is transformed into biomass. They are themselves eaten by secondary predators and are the primary terrestrial consumers of invertebrates, most of which feed on plants. By reducing herbivory, they play a part in increasing the growth of plants and are thus part of a delicately balanced ecosystem.[168]

Little is known about the longevity of frogs and toads in the wild, but some can live for many years. Skeletochronology is a method of examining bones to determine age. Using this method, the ages of mountain yellow-legged frogs (Rana muscosa) were studied, the phalanges of the toes showing seasonal lines where growth slows in winter. The oldest frogs had ten bands, so their age was believed to be 14 years, including the four-year tadpole stage.[169] Captive frogs and toads have been recorded as living for up to 40 years, an age achieved by a European common toad (Bufo bufo). The cane toad (Rhinella marina) has been known to survive 24 years in captivity, and the American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) 14 years.[170] Frogs from temperate climates hibernate during the winter, and four species are known to be able to withstand freezing during this time, including the wood frog (Rana sylvatica).[171]

Parental care

Although care of offspring is poorly understood in frogs, up to an estimated 20% of amphibian species may care for their young in some way.[172] The evolution of parental care in frogs is driven primarily by the size of the water body in which they breed. Those that breed in smaller water bodies tend to have greater and more complex parental care behaviour.[173] Because predation of eggs and larvae is high in large water bodies, some frog species started to lay their eggs on land. Once this happened, the desiccating terrestrial environment demands that one or both parents keep them moist to ensure their survival.[174] The subsequent need to transport hatched tadpoles to a water body required an even more intense form of parental care.[173]

In small pools, predators are mostly absent and competition between tadpoles becomes the variable that constrains their survival. Certain frog species avoid this competition by making use of smaller

Many other diverse forms of parental care are seen in frogs. The tiny male

Some frogs protect their offspring inside their own bodies. Both male and female

Defence

At first sight, frogs seem rather defenceless because of their small size, slow movement, thin skin, and lack of defensive structures, such as spines, claws or teeth. Many use camouflage to avoid detection, the skin often being spotted or streaked in neutral colours that allow a stationary frog to merge into its surroundings. Some can make prodigious leaps, often into water, that help them to evade potential attackers, while many have other defensive adaptations and strategies.[129]

The skin of many frogs contains mild toxic substances called

Some frogs, such as the

Some frogs use bluff or deception. The European common toad (Bufo bufo) adopts a characteristic stance when attacked, inflating its body and standing with its hindquarters raised and its head lowered.

Distribution

Frogs live on every continent except Antarctica, but they are not present on certain islands, especially those far away from continental land masses.

Conservation

In 2006, of 4,035 species of amphibians that depend on water during some lifecycle stage, 1,356 (33.6%) were considered to be threatened. This is likely to be an underestimate because it excludes 1,427 species for which evidence was insufficient to assess their status.

Many environmental scientists believe amphibians, including frogs, are good biological

In a few cases, captive breeding programs have been established and have largely been successful.[211][212] The World Association of Zoos and Aquariums named 2008 as the "Year of the Frog" in order to draw attention to the conservation issues faced by them.[213]

The

Human uses

Culinary

Frog legs are eaten by humans in many parts of the world. Indonesia is the world's largest exporter of frog meat, exporting more than 5,000 tonnes of frog meat each year, mostly to France, Belgium and Luxembourg.[216] Originally, they were supplied from local wild populations, but overexploitation led to a diminution in the supply. This resulted in the development of frog farming and a global trade in frogs. The main importing countries are France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the United States, while the chief exporting nations are Indonesia and China.[217] The annual global trade in the American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana), mostly farmed in China, varies between 1200 and 2400 tonnes.[218]

The

Scientific research

In November, 1970, NASA sent two bullfrogs into space for six days during the Orbiting Frog Otolith mission to test weightlessness.

Frogs are used for dissections in high school and university anatomy classes, often first being injected with coloured substances to enhance contrasts among the biological systems. This practice is declining due to animal welfare concerns, and "digital frogs" are now available for virtual dissection.[221]

Frogs have served as

Frogs are used in cloning research and other branches of

Genomes of Xenopus laevis, X. tropicalis, Rana catesbeiana, Rhinella marina, and Nanorana parkeri have been sequenced and deposited in the NCBI Genome database.[228]

As pets

Due to being inexpensive and relatively easy to care for, many species of frogs and toads have become popular as

More advanced and experienced hobbyists may venture into the keeping and breeding of

Pharmaceutical

Because frog toxins are extraordinarily diverse, they have raised the interest of biochemists as a "natural pharmacy". The alkaloid epibatidine, a painkiller 200 times more potent than morphine, is made by some species of poison dart frogs. Other chemicals isolated from the skins of frogs may offer resistance to HIV infection.[229] Dart poisons are under active investigation for their potential as therapeutic drugs.[230]

It has long been suspected that pre-Columbian

Exudations from the skin of the

Cultural significance

Frogs have been featured in mythology,

References

- ^ a b Frost, Darrel R. (2021) [1998]. "Anura". Amphibian Species of the World. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Cannatella, David C. (1997). "Salientia". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ISBN 978-1-85310-740-5.

- ^ a b Kuzmin, Sergius L. (September 29, 1999). "Bombina bombina". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- ^ Lips, K; Solís, F.; Ibáñez, R.; Jaramillo, C.; Fuenmayor, Q. (2010). "Atelopus zeteki". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2012.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "ἀ". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). "οὐρά". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library.

- OCLC 461974285.

- ^ Bailly, Anatole. "Greek-french dictionary online". www.tabularium.be. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "anuran, n. and adj.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b c d "frog, n.1 and adj.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "frosh | frosk, n.1.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Jerzy Wełna, 'Metathetic and Non-Metathetic Form Selection in Middle English', Studia Anglica Posnaniensia, 30 (2002), 501–18 (p. 504).

- ^ "toad, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "tadpole, n.1.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ ISBN 978-0-13-100849-6.

- ^ Frost, Darrel R. (2023). "Anura Fischer von Waldheim, 1813". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.2. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Duellman, William E. Biology of Amphibians, p. 319, at Google Books

- ^ a b Cannatella, David (January 11, 2008). "Anura". Tree of Life web project. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- JSTOR 1466954.

- S2CID 83925199.

- ^ Kuzmin, S. L. (November 10, 1999). "Pelophylax esculentus". Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- ^ Köhler, Sonja (2003). "Mechanisms for partial reproductive isolation in a Bombina hybrid zone in Romania" (PDF). Dissertation for thesis. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- S2CID 17021360.(subscription required)

- PMID 16012106.

- PMID 17520502.

- PMID 21540408.

- ^ Casselman, Anne (May 21, 2008). ""Frog-amander" fossil may be amphibian missing link". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on May 25, 2008. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- S2CID 205212809.

- S2CID 12023942.

- ^ a b Cannatella, David (1995). "Triadobatrachus massinoti". Tree of Life. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- PMID 30958136.

- ISBN 978-0-949324-87-0. Archived(PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- S2CID 4308225.

- ISBN 978-0-253-34870-8.

- PMID 4528784.

- ^ "Frog evolution linked to dinosaur asteroid strike". BBC News. July 3, 2017. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- PMID 28673970.

- PMID 18287076.

- PMID 32327670.

- from the original on April 23, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- S2CID 86140137.

- .

- PMID 21723399.

- ^ a b Flam, F. (1995). "Finding earliest true frog will help paleontologists understand how frog evolved its jumping ability". Knight Ridder/Tribune News Service. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ "Tiny frog claimed as world's smallest vertebrate". The Guardian. January 12, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- .

- .

- ^ Morphological Variation in Anuran Limbs: Constraints and Novelties

- ^ Morphological and ecological convergence at the lower size limit for vertebrates highlighted by five new miniaturised microhylid frog species from three different Madagascan genera

- ^ a b Minott, Kevin (May 15, 2010). "How frogs jump". National Geographic. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Tesler, P. (1999). "The amazing adaptable frog". Exploratorium:: The museum of science, art and human perception. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Vincent, L. (2001). "Litoria caerulea" (PDF). James Cook University. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 22, 2004. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- .

- S2CID 86616385.

- ^ "Couch's spadefoot (Scaphiopus couchi)". Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ Walker, M. (June 25, 2009). "Legless frogs mystery solved". BBC News.

- ISBN 978-0-691-03281-8.

- S2CID 84796411.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85310-740-5.

- ISBN 978-0-02-612190-3.

- ISBN 978-0-486-21973-8.

- ^ Blackburn, D. C. (November 14, 2002). "Trichobatrachus robustus". AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- JSTOR 1564085.

- ISBN 9780123869203.

- S2CID 59449901.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7232-1503-5.

- .

- S2CID 25692966.

- ^ Boisvert, Adam (October 23, 2007). "Barbourula kalimantanensis". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ Kimball, John (2010). "Animal Circulatory Systems: Three Chambers: The Frog and Lizard". Kimball's Biology Pages. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ Lee, Deborah (April 23, 2010). "Telmatobius culeus". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ The Secret to the Stickiness of Frog Spit | STAO

- PMID 15010487.

- ^ "Frog Digestive System". TutorVista.com. 2010. Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-03-030504-7.

- ^ a b c d "Frog's internal systems". TutorVista.com. 2010. Archived from the original on January 21, 2008. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Duellman, W. E. and L. Trueb (1986). Biology of Amphibians. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company.

- ^ Sever, David M.; Staub, Nancy L. "Hormones, sex accessory structures, and secondary sexual characteristics in amphibians" (PDF). Hormones and Reproduction of Vertebrates – Vol 2: Amphibians. pp. 83–98. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ Laurin, Michel; Gauthier, Jacques A. (2012). "Amniota". Tree of Life Web Project. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0195084764.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85310-740-5.

- PMID 14133069.

- PMID 28193810.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85310-740-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-03281-8.

- PMID 9526013.

- ^ "Bullfrog". Ohio Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original on August 18, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ISSN 0952-8369.

- ^ Nafis, Gary (2012). "Ascaphus truei: Coastal Tailed Frog". California Herps. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ^ Roy, Debjani (1997). "Communication signals and sexual selection in amphibians" (PDF). Current Science. 72: 923–927. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2012.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85310-740-5.

- ISBN 978-0-9832151-0-3.

- ^ Nash, Pat (February 2005). "The RRRRRRRRiveting Life of Tree Frogs". Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- ^ Aristophanes. "The Frogs". Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- PMID 17142687.

- ^ Emmer, Rick (November 24, 1997). "How do frogs survive winter? Why don't they freeze to death?". Scientific American. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- PMID 19737622.

- S2CID 8395980.

- ISBN 9781405107242.

- ^ "Top 10 best jumper animals". Scienceray. Archived from the original on August 10, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-1-85310-740-5.

- PMID 22090204.

- S2CID 13423666.

- ^ JSTOR 3599272.

- ^ a b c Zug, George R.; Duellman, William E. (May 14, 2014). "Anura". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ^ Fitch, H. S. (1956). "An ecological study of the collared lizard (Crotaphytus collaris)". University of Kansas Publications. 8: 213–274.

- PMID 3404074.

- PMID 14691087.

- ^ Pickersgill, M.; Schiøtz, A.; Howell, K.; Minter, L. (2004). "Kassina maculata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ a b "Pipidae". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Duellman, W. E.; Zug, G. R. "Anura: From tadpole to adult". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Farrar, Eugenia; Hey, Jane. "Spea bombifrons". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "Scaphiopodidae". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ Roberts, Dale; Hero, Jean-Marc (2011). "Heleioporus albopunctatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ Staniszewski, Marc (September 30, 1998). "Madagascan Burrowing Frogs: Genus: Scaphiophryne (Boulenger, 1882)". Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ Venesci, M; Raxworthy, C. J.; Nussbaum, R. A.; Glaw, F. (2003). "A revision of the Scaphiophryne marmorata complex of marbled toads from Madagascar, including the description of a new species" (PDF). Herpetological Journal. 13: 69–79. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- PMID 16971337.

- ISBN 978-0-241-90338-4.

- ^ "Phyllomedusa ayeaye". AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- PMID 28564439.

- ^ Shah, Sunny; Tiwari, Rachna (November 29, 2001). "Rhacophorus nigropalmatus". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "Wallace's Flying Frog Rhacophorus nigropalmatus". National Geographic: Animals. September 10, 2010. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-03281-8.

- S2CID 4222519.

- JSTOR 1564026.

- PMID 25551466.

- ISBN 978-0-8014-4374-9.

- (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-691-14968-4.

- ^ Duellman, W. E.; Zug, G. R. "Anura: Egg laying and hatching". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ISBN 978-1-55297-613-5.

- JSTOR 1447647.

- ^ Whittaker, Kellie; Chantasirivisal, Peera (December 2, 2005). "Leptodactylus pentadactylus". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ^ Whittaker, Kellie (June 27, 2007). "Agalychnis callidryas". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- JSTOR 1931088.

- JSTOR 1563783.

- PMID 11607529.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-691-03281-8.

- S2CID 209576535.

- S2CID 32550621.

- ^ Seshadri, K.S. (2015). "Rhacophorid Frogs Breeding in Bamboo: Discovery of a Novel Reproductive Mode from Western Ghats". FrogLog. 23(4) (116): 46–49.

- S2CID 86244218.

- ^ Janzen, Peter (May 10, 2005). "Nannophrys ceylonensis". AmphibiaWeb. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- .

- JSTOR 1445301.

- ISBN 978-0-691-03281-8.

- PMID 29593109.

- ^ Tadpoles eat like crazy before remodeling their guts - Futurity

- PMID 24249298.

- S2CID 255787646.

- ^ Balinsky, Boris Ivan. "Animal development: Metamorphosis". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-691-14968-4.

- ISBN 978-0-691-14968-4.

- ^ Duellman, W. E.; Zug, G. R. "Anura: Feeding habits". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Between fruits, flowers and nectar: The extraordinary diet of the frog Xenohyla truncata

- .

- ^ "Diet of the Neotropical frog Leptodactylus mystaceus" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 2, 2014.

- ^ Camera, Bruno F.; Krinski, Diones; Calvo, Isabella A. (February 4, 2014). "Diet of the Neotropical frog Leptodactylus mystaceus (Anura: Leptodactylidae)" (PDF). Herpetology Notes. 7: 31–36. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-691-14968-4.

- ^ Graham, Donna. "Northern leopard frog (Rana pipiens)". An Educator's Guide to South Dakota's Natural Resources. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2012.

- PMID 538731. Archived from the original(PDF) on September 27, 2011.

- S2CID 86237494.(subscription required)

- ^ Slavens, Frank; Slavens, Kate. "Frog and toad index". Longevity. Archived from the original on August 18, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- PMID 2180324.

- ISBN 978-0-12-004525-9.

- ^ S2CID 20270737.

- S2CID 85122799.

- S2CID 29546555.

- S2CID 82263880. Archived from the original(PDF) on April 4, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- JSTOR 1565037.

- .

- ^ "Common midwife toad, Alytes obstetricans". Repties et Amphibiens de France. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- ^ "Proteins of frog foam nests". University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- PMID 20106853.

- ^ "Assa darlingtoni". Frogs Australia Network. 2005. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ Semeyn, E. (2002). "Rheobatrachus silus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^ Sandmeier, Fran (March 12, 2001). "Rhinoderma darwinii". AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- S2CID 25434883.

- PMID 16525472.

- PMID 6836257.

- ISBN 978-0-916984-16-8.

- ^ Duellman, W. E. (1978). "The Biology of an Equatorial Herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador" (PDF). University of Kansas Museum of Natural History Miscellaneous Publication. 65. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 4, 2011.

- PMID 15128938.

- PMID 11975476.

- ^ Grant, T. "Poison Dart Frog Vivarium". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-00-219964-3.

- JSTOR 1445987.

- ^ "Freaky Frogs". National Geographic Explorer. Archived from the original on March 6, 2004. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ Ferrell, Vance (March 4, 2012). "Geographical Distribution". Evolution Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Evolution Facts. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ Ryan, Paddy (September 25, 2011). "Story: Frogs". The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- S2CID 13067241.

- ^ "Cyclorana platycephala". Frogs Australia Network. February 23, 2005. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ Hoekstra, J. M.; Molnar, J. L.; Jennings, M.; Revenga, C.; Spalding, M. D.; Boucher, T. M.; Robertson, J. C.; Heibel, T. J.; Ellison, K. (2010). "Number of Globally Threatened Amphibian Species by Freshwater Ecoregion". The Atlas of Global Conservation: Changes, Challenges, and Opportunities to Make a Difference. The Nature Conservancy. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- S2CID 86238651. Archived from the original(PDF) on October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- S2CID 85382659.

- ^ "Worldwide Amphibian Declines: How big is the problem, what are the causes and what can be done?". AmphibiaWeb. January 22, 2009. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ^ "Frog population decrease mostly due to traffic". New Scientist. July 7, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- PMID 20202208.

- PMID 16870853.

- ISBN 978-0-14-024646-9.

- S2CID 55870526.

- doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2003)001[0087:TCODA]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original(PDF) on October 29, 2013.

- PMID 10620528.

- ^ Black, Richard (October 2, 2005). "New frog centre for London Zoo". BBC News. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ "National recovery plan for the Southern Corroboree Frog (Pseudophryne corroboree): 5. Previous recovery actions". Environment.gov.au. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved November 3, 2008.

- ^ "2008: Year of the Frog". January 15, 2008. Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-670-90123-4.

- ^ Cameron, Elizabeth (September 6, 2012). "Cane toad". Australian Museum. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ ̺Brahic, Catherine (January 20, 2009). "Appetite For Frogs' Legs Harming Wild Populations". abc news.

- S2CID 1837255.

- ^ "Cultured Aquatic Species Information Programme: Rana catesbeiana". FAO: Fisheries and Aquaculture Department. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ Ryan Schuessler (January 28, 2016). "The Mountain Chicken Frog's First Problem: It Tastes Like..." National Geographic News. Archived from the original on January 29, 2016.

- ^ Mark Twain; Charles Dudley Warner (1904). The Writings of Mark Twain [pseud.].: A tramp abroad. Harper & Bros. p. 263.

- ^ "California Schools Leading Race to Stop Dissections". Animal Welfare Institute. April 25, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ Wells, David Ames (1859). The science of common things: a familiar explanation of the first principles of physical science. For schools, families, and young students. Ivison, Phinney, Blakeman. p. 290.

- ^ "Stannius ligature". Biology online. October 3, 2005. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- PMID 8849876.

- ^ Brownlee, Christen. "Nuclear Transfer: Bringing in the Clones". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ Browder, L.; Iten, L., eds. (1998). "Xenopus as a Model System in Developmental Biology". Dynamic Development. University of Calgary. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ^ Klein, S. "Developing the potential of Xenopus tropicalis as a genetic model". Trans-NIH Xenopus Working Group. Retrieved March 9, 2006.

- ^ "Genome List – Genome". NCBI. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- PMID 16140737.

- PMID 15993556.

- PMID 8895112.

- PMID 8486435.

- ^ hdl:2246/1286.

- ISBN 978-0-691-14968-4.

- ISBN 978-1-86189-920-0.

- ISBN 978-1-86189-920-0.

Further reading

- Beltz, Ellin (2005). Frogs: Inside their Remarkable World. Firefly Books. ISBN 978-1-55297-869-6.

- Cogger, H. G.; Zweifel, R. G.; Kirschner, D. (2004). Encyclopedia of Reptiles & Amphibians (2nd ed.). Fog City Press. ISBN 978-1-877019-69-2.

- Estes, R., and O. A. Reig. (1973). "The early fossil record of frogs: a review of the evidence." pp. 11–63 In J. L. Vial (Ed.), Evolutionary Biology of the Anurans: Contemporary Research on Major Problems. University of Missouri Press, Columbia.

- Gissi, Carmela; San Mauro, Diego; Pesole, Graziano; Zardoya, Rafael (February 2006). "Mitochondrial phylogeny of Anura (Amphibia): A case study of congruent phylogenetic reconstruction using amino acid and nucleotide characters". Gene. 366 (2): 228–237. PMID 16307849.

- Holman, J. A. (2004). Fossil Frogs and Toads of North America. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34280-5.

- San Mauro, Diego; Vences, Miguel; Alcobendas, Marina; Zardoya, Rafael; Meyer, Axel (May 2005). "Initial diversification of living amphibians predated the breakup of Pangaea". American Naturalist. 165 (5): 590–599. S2CID 17021360.

- Tyler, M. J. (1994). Australian Frogs A Natural History. Reed Books. ISBN 978-0-7301-0468-1.

External links

- AmphibiaWeb

- Gallery of Frogs – Photography and images of various frog species

- The Whole Frog Project – Virtual frog dissection and anatomy

- "Disappearance of toads, frogs has some scientists worried" San Francisco Chronicle, 20 April 1992

- Amphibian photo gallery by scientific name – Features many unusual frogs

- Scientific American: Researchers Pinpoint Source of Poison Frogs' Deadly Defenses

Media

- Time-lapse video showing the egg's development until hatching

- Frog vocalisations from around the world – From the British Library Sound Archive

- Frog calls – From Manitoba, Canada