Fruit

In

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as

In common language usage, fruit normally means the seed-associated fleshy structures (or produce) of plants that typically are sweet or sour and edible in the raw state, such as apples, bananas, grapes, lemons, oranges, and strawberries. In botanical usage, the term fruit also includes many structures that are not commonly called 'fruits' in everyday language, such as nuts, bean pods, corn kernels, tomatoes, and wheat grains.[2][3]

Botanical vs. culinary

Many common language terms used for fruit and seeds differ from botanical classifications. For example, in botany, a fruit is a ripened

In culinary language, a

Examples of botanically classified fruit that are typically called vegetables include

Botanically, a cereal grain, such as corn, rice, or wheat is a kind of fruit (termed a caryopsis). However, the fruit wall is thin and fused to the seed coat, so almost all the edible grain-fruit is actually a seed.[7]

Structure

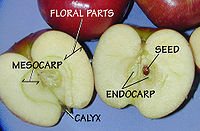

The outer layer, often edible, of most fruits is called the pericarp. Typically formed from the ovary, it surrounds the seeds; in some species, however, other structural tissues contribute to or form the edible portion. The pericarp may be described in three layers from outer to inner, i.e., the epicarp, mesocarp and endocarp.

Fruit that bears a prominent pointed terminal projection is said to be beaked.[8]

Development

A fruit results from the fertilizing and maturing of one or more flowers. The

Ovules are fertilized in a process that starts with pollination, which is the movement of pollen from the stamens to the stigma-style-ovary system within the flower-head. After pollination, a pollen tube grows from the (deposited) pollen through the stigma down the style into the ovary to the ovule. Two sperm are transferred from the pollen to a megagametophyte. Within the megagametophyte, one sperm unites with the egg, forming a zygote, while the second sperm enters the central cell forming the endosperm mother cell, which completes the double fertilization process.[11][12] Later, the zygote will give rise to the embryo of the seed, and the endosperm mother cell will give rise to endosperm, a nutritive tissue used by the embryo.

As the ovules develop into seeds, the ovary begins to ripen and the ovary wall, the pericarp, may become fleshy (as in berries or drupes), or it may form a hard outer covering (as in nuts). In some multi-seeded fruits, the extent to which a fleshy structure develops is proportional to the number of fertilized ovules.[13] The pericarp typically is differentiated into two or three distinct layers; these are called the exocarp (outer layer, also called epicarp), mesocarp (middle layer), and endocarp (inner layer).

In some fruits, the

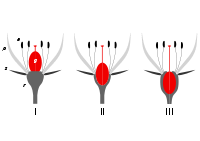

Because several parts of the flower besides the ovary may contribute to the structure of a fruit, it is important to understand how a particular fruit forms.[3] There are three general modes of fruit development:

- Apocarpous fruits develop from a single flower (while having one or more separate, unfused, carpels); they are the simple fruits.

- Syncarpous fruits develop from a single gynoecium (having two or more carpels fused together).

- Multiple fruits form from many flowers – i.e., an inflorescence of flowers.

-

The development sequence of a typicalnectarine (Prunus persica) over a 7.5-month period, from bud formation in early winter to fruit ripeningin midsummer

-

The parts of a flower, showing the stigma-style-ovary system.

-

An apple is a simple, fleshy fruit. Key parts are the epicarp, or exocarp, or outer skin (not labelled); and the mesocarp and endocarp (labelled).

-

Insertion point: There are three positions of insertion of the ovary at the base of a flower: I superior; II half-inferior; III inferior. The 'insertion point' is where theandroeciumparts (a), the petals (p), and the sepals (s) all converge and attach to the receptacle (r). (Ovary=gynoecium (g).)

-

In thenoni, flowers are produced in time-sequence along the stem. It is possible to see a progression of flowering, fruit development, and fruit ripening.

-

Twin apples.

Classification of fruits

Consistent with the three modes of fruit development, plant scientists have classified fruits into three main groups: simple fruits, aggregate fruits, and multiple (or composite) fruits.

While the section of a

Simple fruits

Simple fruits are the result of the ripening-to-fruit of a simple or compound ovary in a single flower with a single

To distribute their seeds, dry fruits may split open and discharge their seeds to the winds, which is called

Types of dry simple fruits, (with examples) include:

- Achene – most commonly seen in aggregate fruits (e.g., strawberry, see below).

- Capsule – (Brazil nut: botanically, it is not a nut).

- oats, barley).

- dandelion).

- Fibrous drupe – (coconut, walnut: botanically, neither is a true nut.).

- ).

- Legume – (bean, pea, peanut: botanically, the peanut is the seed of a legume, not a nut).

- indehiscent legume: (sweet vetch or wild potato).

- Nut – (beechnut, hazelnut, acorn (of the oak): botanically, these are true nuts).

- ).

- Schizocarp, see below – (carrot seed).

- Silique – (radish seed).

- Silicle – (shepherd's purse).

- beet, Rumex).

Fruits in which part or all of the

Types of fleshy simple fruits, (with examples) include:

- Berry – the berry is the most common type of fleshy fruit. The entire outer layer of the ovary wall ripens into a potentially edible "pericarp", (see below).

- .

- .

Berries

Berries are a type of simple fleshy fruit that issue from a single ovary.[19] (The ovary itself may be compound, with several carpels.) The botanical term true berry includes grapes, currants, cucumbers, eggplants (aubergines), tomatoes, chili peppers, and bananas, but excludes certain fruits that are called "-berry" by culinary custom or by common usage of the term – such as strawberries and raspberries. Berries may be formed from one or more carpels (i.e., from the simple or compound ovary) from the same, single flower. Seeds typically are embedded in the fleshy interior of the ovary.

Examples include:

- Tomato – in culinary terms, the tomato is regarded as a vegetable, but it is botanically classified as a fruit and a berry.[20]

- Banana – the fruit has been described as a "leathery berry".[21] In cultivated varieties, the seeds are diminished nearly to non-existence.

- Pepo – berries with skin that is hardened: cucurbits, including gourds, squash, melons.

- Hesperidium – berries with a rind and a juicy interior: most citrus fruit.

- Cranberry, gooseberry, redcurrant, grape.

The strawberry, regardless of its appearance, is classified as a dry, not a fleshy fruit. Botanically, it is not a berry; it is an aggregate-accessory fruit, the latter term meaning the fleshy part is derived not from the plant's ovaries but from the receptacle that holds the ovaries.[22] Numerous dry achenes are attached to the outside of the fruit-flesh; they appear to be seeds but each is actually an ovary of a flower, with a seed inside.[22]

Schizocarps are dry fruits, though some appear to be fleshy. They originate from syncarpous ovaries but do not actually dehisce; rather, they split into segments with one or more seeds. They include a number of different forms from a wide range of families, including carrot, parsnip, parsley, cumin.[14]

Aggregate fruits

An aggregate fruit is also called an aggregation, or

Different types of aggregate fruits can produce different etaerios, such as achenes, drupelets, follicles, and berries.

- For example, the Ranunculaceae species, including Clematis and Ranunculus, produces an etaerio of achenes;

- drupelets;

- Calotropis species: an etaerio of follicles fruit;

Some other broadly recognized species and their etaerios (or aggregations) are:

- cypselas.

- Tuliptree; fruit is an aggregation of samaras.

- Magnolia and peony; fruit is an aggregation of follicles.

- American sweet gum; fruit is an aggregation of capsules.

- Sycamore; fruit is an aggregation of achenes.

The pistils of the

Multiple fruits

A multiple fruit is formed from a cluster of flowers, (a 'multiple' of flowers) – also called an

Progressive stages of multiple flowering and fruit development can be observed on a single branch of the Indian mulberry, or

Accessory fruit forms

Fruits may incorporate tissues derived from other floral parts besides the ovary, including the receptacle, hypanthium, petals, or sepals. Accessory fruits occur in all three classes of fruit development – simple, aggregate, and multiple. Accessory fruits are frequently designated by the hyphenated term showing both characters. For example, a pineapple is a multiple-accessory fruit, a blackberry is an aggregate-accessory fruit, and an apple is a simple-accessory fruit.

Table of fleshy fruit examples

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Simple fleshy fruit | stone fruit, pome

|

| Aggregate fruit | Boysenberry, lilium, magnolia, raspberry, pawpaw, blackberry, strawberry |

| Multiple fruit | mulberry, pineapple

|

| True berry | |

| True berry: Pepo | Cucumber, gourd, melon, pumpkin |

| True berry: Hesperidium | Grapefruit, lemon, lime, orange |

| Accessory fruit | Apple, rose hip, stone fruit, pineapple, blackberry, strawberry |

Seedless fruits

Seedlessness is an important feature of some fruits of commerce. Commercial

Seed dissemination

Variations in fruit structures largely depend on the

Some fruits present their outer skins or shells coated with spikes or hooked burrs; these evolved either to deter would-be foragers from feeding on them or to serve to attach themselves to the hair, feathers, legs, or clothing of animals, thereby using them as dispersal agents. These plants are termed

By developments of mutual evolution, the fleshy produce of fruits typically appeals to hungry animals, such that the seeds contained within are taken in, carried away, and later deposited (i.e., defecated) at a distance from the parent plant. Likewise, the nutritious, oily kernels of nuts typically motivate birds and squirrels to hoard them, burying them in soil to retrieve later during the winter of scarcity; thereby, uneaten seeds are sown effectively under natural conditions to germinate and grow a new plant some distance away from the parent.[4]

Other fruits have evolved flattened and elongated wings or helicopter-like blades, e.g.,

Some fruits have evolved propulsive mechanisms that fling seeds substantial distances – perhaps up to 100 m (330 ft) in the case of the

Food uses

Fruits are also used for socializing and gift-giving in the form of

Typically, many botanical fruits – "vegetables" in culinary parlance – (including tomato, green beans, leaf greens, bell pepper, cucumber, eggplant, okra, pumpkin, squash, zucchini) are bought and sold daily in fresh produce markets and greengroceries and carried back to kitchens, at home or restaurant, for preparation of meals.[39]

Storage

All fruits benefit from proper post-harvest care, and in many fruits, the plant hormone

Nutritional value

Various culinary fruits provide significant amounts of fiber and water, and many are generally high in vitamin C.[41] An overview of numerous studies showed that fruits (e.g., whole apples or whole oranges) are satisfying (filling) by simply eating and chewing them.[42]

The dietary fiber consumed in eating fruit promotes

Food safety

For

All fruits and vegetables should be rinsed before eating. This recommendation also applies to produce with rinds or skins that are not eaten. It should be done just before preparing or eating to avoid premature spoilage.

Fruits and vegetables should be kept separate from raw foods like meat, poultry, and seafood, as well as from utensils that have come in contact with raw foods. Fruits and vegetables that are not going to be cooked should be thrown away if they have touched raw meat, poultry, seafood, or eggs.

All cut, peeled, or cooked fruits and vegetables should be refrigerated within two hours. After a certain time, harmful bacteria may grow on them and increase the risk of foodborne illness.[49]

Allergies

Fruit allergies make up about 10 percent of all food-related allergies.[50][51]

Nonfood uses

Because fruits have been such a major part of the human diet, various cultures have developed many different uses for fruits they do not depend on for food. For example:

- Bayberry fruits provide a wax often used to make candles;[53]

- Many dry fruits are used as decorations or in dried flower arrangements (e.g.,

- Fruits of

- Osage orange fruits are used to repel cockroaches.[56]

- Many fruits provide

- Dried gourds are used as bird houses, cups, decorations, dishes, musical instruments, and water jugs.

- Pumpkins are carved into Jack-o'-lanterns for Halloween.[58]

- The fibrous core of the mature and dry Luffa fruit is used as a sponge.[59]

- The spiny fruit of

- Coir fiber from coconut shells is used for brushes, doormats, floor tiles, insulation, mattresses, sacking, and as a growing medium for container plants. The shell of the coconut fruit is used to make bird houses, bowls, cups, musical instruments, and souvenir heads.[61]

- The hard and colorful grain fruits of Job's tears are used as decorative beads for jewelry, garments, and ritual objects.[62]

- Fruit is often a subject of still life paintings.

See also

- Fruit tree

- Fruitarianism

- List of countries by fruit production

- List of culinary fruits

- List of foods

- List of fruit dishes

References

- ISBN 978-0-8493-2327-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-1-56022-950-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7637-2134-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ For a Supreme Court of the United States ruling on the matter, see Nix v. Hedden.

- ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-2327-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ "Glossary of Botanical Terms". FloraBase. Western Australian Herbarium. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ Esau, K. 1977. Anatomy of seed plants. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- ^ [1] Archived December 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-0-7637-2134-3.

- ISBN 978-0-471-02114-8.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-2134-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57808-351-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ "Sporophore from Encyclopædia Britannica". Archived from the original on 2011-02-22.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-56022-950-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-1-56022-950-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-0-231-07328-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ISBN 978-1-118-35263-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ^ Mark Abadi (26 May 2018). "A tomato is actually a fruit — but it's a vegetable at the same time". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Smith, James P. (1977). Vascular Plant Families. Eureka, Calif.: Mad River Press. ISBN 978-0-916422-07-3.

- ^ ISBN 0-471-24520-8

- ISBN 978-81-7133-896-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2015-11-28.

- ^ "Rgukt.in" (PDF). www.rkv.rgukt.in.[permanent dead link]

- ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-1-56022-950-6. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-0-12-812163-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ]

- ^ ISBN 978-0-88192-655-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-0-88192-562-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-0-88192-562-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-10-06.

- ISBN 978-0-88192-562-3.

- ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ISBN 978-0-8342-1337-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ NFU, A guide to British fruit and vegetables Archived 2023-06-25 at the Wayback Machine, Countryside, published 6 October 2022, accessed 25 June 2023

- ^ "Best Gift Baskets for the Holidays - Consumer Reports". www.consumerreports.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- ^ O'Connor, Clare. "How Edible Arrangements Sold $500 Million Of Fruit Bouquets In 2013". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2022-05-21. Retrieved 2021-03-13.

- ISBN 978-0-684-80001-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ Why Cold Chain for Fruits: Kohli, Pawanexh (2008). "Fruits and Vegetables Post-Harvest Care: The Basics". Crosstree Techno-visors. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-04. Retrieved 2009-09-28.

- ^ Hulme AC (1970). The Biochemistry of Fruits and Their Products. London & New York: Academic Press.

- PMID 7498104.

- PMID 9925120.

- PMID 28338764. Archived from the original on 2017-10-06. Retrieved 2021-09-12.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - S2CID 73455999. Archived from the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2023-06-19.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - PMID 23245609.

- PMID 25073782.

- S2CID 58628014.

- ^ "Nutrition for Everyone: Fruits and Vegetables – DNPAO – CDC". fruitsandveggiesmatter.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-05-09.

- ^ "Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America". Aafa.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-06. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ISBN 978-0-9801584-4-1. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ "Porcelain vine". The Morton Arboretum. Archived from the original on 2020-12-25. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ISBN 978-0-7387-0079-3. Archivedfrom the original on January 30, 2024. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-88192-619-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ISBN 978-0-312-20667-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ]

- ISBN 978-0-486-22688-0. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ Nathaniel Hawthorne, "The Great Carbuncle", in Twice-Told Tales, 1837: Hide it [the great carbuncle] under thy cloak, say'st thou? Why, it will gleam through the holes, and make thee look like a jack-o'-lantern!

- ^ "Grow Your Own Loofah Sponges at Home for Pennies (Yes, You Really Can!)". Dr. Axe. Archived from the original on 2023-01-02. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ISBN 978-0-471-29976-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ^ "The Many Uses of the Coconut". The Coconut Museum. Archived from the original on 2006-09-06. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- ^ Watt, George (1904). "Coix spp. (Job's tears)". Agricultural Ledger. 11 (13): 191. Archived from the original on 2024-01-30. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

Further reading

- Gollner, Adam J. (2010). The Fruit Hunters: A Story of Nature, Adventure, Commerce, and Obsession. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-7432-9695-3.

- Watson, R. R., and Preedy, V.R. (2010, eds.). Bioactive Foods in Promoting Health: Fruits and Vegetables. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-374628-3.

External links

- Images of fruit development from flowers at bioimages.Vanderbilt.edu (archived 18 February 2007)

- Fruit and seed dispersal images at bioimages.Vanderbilt.edu (archived 25 April 2017)

- Fruit Facts (Archived 2020-07-12 at the Wayback Machine from California Rare Fruit Growers, Inc.)

- Photo ID of Fruits (Archived 2021-01-09 at the Wayback Machine by Capt. Pawanexh Kohli)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.