Fungus

| Fungi | |

|---|---|

| |

Clockwise from top left:

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Obazoa |

| (unranked): | Opisthokonta |

| Clade: | Holomycota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi (L.) R.T.Moore[1] |

| Subkingdoms/Phyla | |

| |

A fungus (pl.: fungi

A characteristic that places fungi in a different kingdom from

Abundant worldwide, most fungi are inconspicuous because of the small size of their structures, and their

The fungus kingdom encompasses an enormous diversity of

Etymology

The English word fungus is directly adopted from the

The word mycology is derived from the Greek mykes (μύκης 'mushroom') and logos (λόγος 'discourse').[12] It denotes the scientific study of fungi. The Latin adjectival form of "mycology" (mycologicæ) appeared as early as 1796 in a book on the subject by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon.[13] The word appeared in English as early as 1824 in a book by Robert Kaye Greville.[14] In 1836 the English naturalist Miles Joseph Berkeley's publication The English Flora of Sir James Edward Smith, Vol. 5. also refers to mycology as the study of fungi.[10][15]

A group of all the fungi present in a particular region is known as

Characteristics

Before the introduction of

Shared features:

- With other 80S type.[23] They have a characteristic range of soluble carbohydrates and storage compounds, including sugar alcohols (e.g., mannitol), disaccharides, (e.g., trehalose), and polysaccharides (e.g., glycogen, which is also found in animals[24]).

- With animals: Fungi lack chloroplasts and are heterotrophic organisms and so require preformed organic compounds as energy sources.[25]

- With plants: Fungi have a cell wallhaploid nuclei.[28]

- With

- The cells of most fungi grow as tubular, elongated, and thread-like (filamentous) structures called vesicles—cellular structures consisting of proteins, lipids, and other organic molecules—called the Spitzenkörper.[31] Both fungi and oomycetes grow as filamentous hyphal cells.[32] In contrast, similar-looking organisms, such as filamentous green algae, grow by repeated cell division within a chain of cells.[24] There are also single-celled fungi (yeasts) that do not form hyphae, and some fungi have both hyphal and yeast forms.[33]

- In common with some plant and animal species, more than one hundred fungal species display bioluminescence.[34]

Unique features:

- Some species grow as unicellular yeasts that reproduce by Dimorphic fungi can switch between a yeast phase and a hyphal phase in response to environmental conditions.[33]

- The fungal cell wall is made of a

Most fungi lack an efficient system for the long-distance transport of water and nutrients, such as the

Diversity

Fungi have a worldwide distribution, and grow in a wide range of habitats, including extreme environments such as

As of 2020,[update] around 148,000 species of fungi have been described by taxonomists,[7] but the global biodiversity of the fungus kingdom is not fully understood.[49] A 2017 estimate suggests there may be between 2.2 and 3.8 million species.[6] The number of new fungi species discovered yearly has increased from 1,000 to 1,500 per year about 10 years ago, to about 2,000 with a peak of more than 2,500 species in 2016. In the year 2019, 1,882 new species of fungi were described, and it was estimated that more than 90% of fungi remain unknown.[7] The following year, 2,905 new species were described—the highest annual record of new fungus names.[50] In mycology, species have historically been distinguished by a variety of methods and concepts. Classification based on morphological characteristics, such as the size and shape of spores or fruiting structures, has traditionally dominated fungal taxonomy.[51] Species may also be distinguished by their biochemical and physiological characteristics, such as their ability to metabolize certain biochemicals, or their reaction to chemical tests. The biological species concept discriminates species based on their ability to mate. The application of molecular tools, such as DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, to study diversity has greatly enhanced the resolution and added robustness to estimates of genetic diversity within various taxonomic groups.[52]

Mycology

The use of fungi by humans dates back to prehistory;

History

Mycology became a systematic science after the development of the

Morphology

Microscopic structures

Most fungi grow as

Many species have developed specialized hyphal structures for nutrient uptake from living hosts; examples include

Although fungi are

Macroscopic structures

Fungal mycelia can become visible to the naked eye, for example, on various surfaces and

The

Growth and physiology

The growth of fungi as hyphae on or in solid substrates or as single cells in aquatic environments is adapted for the efficient extraction of nutrients, because these growth forms have high

The mechanical pressure exerted by the appressorium is generated from physiological processes that increase intracellular

Fungi are traditionally considered

Reproduction

Fungal reproduction is complex, reflecting the differences in lifestyles and genetic makeup within this diverse kingdom of organisms.

Asexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction with

Most fungi have both a

In ascomycetes, dikaryotic hyphae of the

Sexual reproduction in basidiomycetes is similar to that of the ascomycetes. Compatible haploid hyphae fuse to produce a dikaryotic mycelium. However, the dikaryotic phase is more extensive in the basidiomycetes, often also present in the vegetatively growing mycelium. A specialized anatomical structure, called a

In fungi formerly classified as

Spore dispersal

The spores of most of the researched species of fungi are transported by wind.

Homothallism

In

Other sexual processes

Besides regular sexual reproduction with meiosis, certain fungi, such as those in the genera

Evolution

In contrast to

The earliest fossils possessing features typical of fungi date to the

In May 2019, scientists reported the discovery of a fossilized fungus, named Ourasphaira giraldae, in the Canadian Arctic, that may have grown on land a billion years ago, well before plants were living on land.[126][127][128] Pyritized fungus-like microfossils preserved in the basal Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation (~635 Ma) have been reported in South China.[129] Earlier, it had been presumed that the fungi colonized the land during the Cambrian (542–488.3 Ma), also long before land plants.[130] Fossilized hyphae and spores recovered from the Ordovician of Wisconsin (460 Ma) resemble modern-day Glomerales, and existed at a time when the land flora likely consisted of only non-vascular bryophyte-like plants.[131] Prototaxites, which was probably a fungus or lichen, would have been the tallest organism of the late Silurian and early Devonian. Fungal fossils do not become common and uncontroversial until the early Devonian (416–359.2 Ma), when they occur abundantly in the Rhynie chert, mostly as Zygomycota and Chytridiomycota.[130][132][133] At about this same time, approximately 400 Ma, the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota diverged,[134] and all modern classes of fungi were present by the Late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian, 318.1–299 Ma).[135]

Lichens formed a component of the early terrestrial ecosystems, and the estimated age of the oldest terrestrial lichen fossil is 415 Ma;

Some time after the

Sixty-five million years ago, immediately after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event that famously killed off most dinosaurs, there was a dramatic increase in evidence of fungi; apparently the death of most plant and animal species led to a huge fungal bloom like "a massive compost heap".[146]

Taxonomy

Although commonly included in botany curricula and textbooks, fungi are more closely related to

There is no unique generally accepted system at the higher taxonomic levels and there are frequent name changes at every level, from species upwards. Efforts among researchers are now underway to establish and encourage usage of a unified and more consistent

The 2007 classification of Kingdom Fungi is the result of a large-scale collaborative research effort involving dozens of mycologists and other scientists working on fungal taxonomy.

Zoosporia

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Basidiomycota |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ascomycota |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taxonomic groups

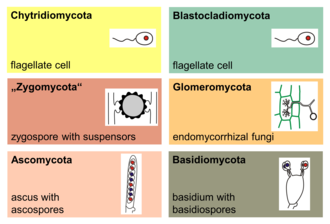

The major phyla (sometimes called divisions) of fungi have been classified mainly on the basis of characteristics of their sexual reproductive structures. As of 2019[update], nine major lineages have been identified: Opisthosporidia, Chytridiomycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Zoopagomycotina, Mucoromycota, Glomeromycota, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota.[156]

Phylogenetic analysis has demonstrated that the Microsporidia, unicellular parasites of animals and protists, are fairly recent and highly derived endobiotic fungi (living within the tissue of another species).[123] Previously considered to be "primitive" protozoa, they are now thought to be either a basal branch of the Fungi, or a sister group–each other's closest evolutionary relative.[157]

The

The Blastocladiomycota were previously considered a taxonomic clade within the Chytridiomycota. Molecular data and ultrastructural characteristics, however, place the Blastocladiomycota as a sister clade to the Zygomycota, Glomeromycota, and Dikarya (Ascomycota and Basidiomycota). The blastocladiomycetes are saprotrophs, feeding on decomposing organic matter, and they are parasites of all eukaryotic groups. Unlike their close relatives, the chytrids, most of which exhibit zygotic meiosis, the blastocladiomycetes undergo sporic meiosis.[123]

The

Members of the

The

Members of the

Fungus-like organisms

Because of similarities in morphology and lifestyle, the

Unlike true fungi, the

The

The Rozellida clade, including the "ex-chytrid" Rozella, is a genetically disparate group known mostly from environmental DNA sequences that is a sister group to fungi.[156] Members of the group that have been isolated lack the chitinous cell wall that is characteristic of fungi. Alternatively, Rozella can be classified as a basal fungal group.[148]

The

Ecology

Although often inconspicuous, fungi occur in every environment on

Symbiosis

Many fungi have important

With plants

The mycorrhizal symbiosis is ancient, dating back to at least 400 million years.[160] It often increases the plant's uptake of inorganic compounds, such as nitrate and phosphate from soils having low concentrations of these key plant nutrients.[174][183] The fungal partners may also mediate plant-to-plant transfer of carbohydrates and other nutrients.[184] Such mycorrhizal communities are called "common mycorrhizal networks".[185][186] A special case of mycorrhiza is myco-heterotrophy, whereby the plant parasitizes the fungus, obtaining all of its nutrients from its fungal symbiont.[187] Some fungal species inhabit the tissues inside roots, stems, and leaves, in which case they are called endophytes.[188] Similar to mycorrhiza, endophytic colonization by fungi may benefit both symbionts; for example, endophytes of grasses impart to their host increased resistance to herbivores and other environmental stresses and receive food and shelter from the plant in return.[189]

With algae and cyanobacteria

With insects

Many insects also engage in

As pathogens and parasites

Many fungi are

Some fungi can cause serious diseases in humans, several of which may be fatal if untreated. These include

As targets of mycoparasites

Organisms that parasitize fungi are known as

Communication

There appears to be electrical communication between fungi in word-like components according to spiking characteristics.[222]

Possible impact on climate

According to a study published in the academic journal Current Biology, fungi can soak from the atmosphere around 36% of global fossil fuel greenhouse gas emissions.[223][224]

Mycotoxins

Many fungi produce

Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites (or natural products), and research has established the existence of biochemical pathways solely for the purpose of producing mycotoxins and other natural products in fungi.[39] Mycotoxins may provide fitness benefits in terms of physiological adaptation, competition with other microbes and fungi, and protection from consumption (fungivory).[227][228] Many fungal secondary metabolites (or derivatives) are used medically, as described under Human use below.

Pathogenic mechanisms

Human use

The human use of fungi for food preparation or preservation and other purposes is extensive and has a long history.

Therapeutic uses

Modern chemotherapeutics

Many species produce metabolites that are major sources of pharmacologically active drugs.

Antibiotics

Particularly important are the antibiotics, including the

Other

Other drugs produced by fungi include

Traditional medicine

Certain mushrooms are used as supposed therapeutics in folk medicine practices, such as traditional Chinese medicine. Mushrooms with a history of such use include Agaricus subrufescens,[251][255] Ganoderma lucidum,[256] and Ophiocordyceps sinensis.[257]

Cultured foods

In food

Many other mushroom species are

Certain types of cheeses require inoculation of milk curds with fungal species that impart a unique flavor and texture to the cheese. Examples include the blue color in cheeses such as Stilton or Roquefort, which are made by inoculation with Penicillium roqueforti.[266] Molds used in cheese production are non-toxic and are thus safe for human consumption; however, mycotoxins (e.g., aflatoxins, roquefortine C, patulin, or others) may accumulate because of growth of other fungi during cheese ripening or storage.[267]

Poisonous fungi

Many mushroom species are

As it is difficult to accurately identify a safe mushroom without proper training and knowledge, it is often advised to assume that a wild mushroom is poisonous and not to consume it.[273][274]

Pest control

In agriculture, fungi may be useful if they actively compete for nutrients and space with

Bioremediation

Certain fungi, in particular

Model organisms

Several pivotal discoveries in biology were made by researchers using fungi as

Others

Fungi are used extensively to produce industrial chemicals like

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Moore RT (1980). "Taxonomic proposals for the classification of marine yeasts and other yeast-like fungi including the smuts". Botanica Marina. 23: 361–373.

- ^ /ˈfʌndʒaɪ/ ⓘ, /ˈfʌŋɡaɪ/ ⓘ, /ˈfʌŋɡi/ ⓘ or /ˈfʌndʒi/ ⓘ. The first two pronunciations are favored more in the US and the others in the UK, however all pronunciations can be heard in any English-speaking country.

- ^ "Fungus". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- PMID 5762760.

- S2CID 6557779.

- ^ PMID 28752818.

- ^ hdl:1854/LU-8705210.

- PMID 28741610.

- ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- ^ a b Ainsworth 1976, p. 2.

- Walter de Gruyter.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 1.

- ^ Persoon CH (1796). Observationes Mycologicae: Part 1 (in Latin). Leipzig, (Germany): Peter Philipp Wolf. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Greville RK (1824). Scottish Cryptogamie Flora: Or Coloured Figures and Descriptions of Cryptogamic Plants, Belonging Chiefly to the Order Fungi. Vol. 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Maclachland and Stewart. p. 65. From p. 65: "This little plant will probably not prove rare in Great Britain, when mycology shall be more studied."

- ^ Smith JE (1836). Hooker WJ, Berkeley MJ (eds.). The English Flora of Sir James Edward Smith. Vol. 5, part II: "Class XXIV. Cryptogamia". London, England: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman. p. 7. From p. 7: "This has arisen, I conceive, partly from the practical difficulty of preserving specimens for the herbarium, partly from the absence of any general work, adapted to the immense advances which have of late years been made in the study of Mycology."

- ^ "LIAS Glossary". Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- hdl:11336/88035.

- IUCN SSC. 2021. Archived from the original(PDF) on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

The IUCN Species Survival Commission calls for the due recognition of fungi as major components of biodiversity in legislation and policy. It fully endorses the Fauna Flora Funga Initiative and asks that the phrases animals and plants and fauna and flora be replaced with animals, fungi, and plants and fauna, flora, and funga.

- ^ "Fifth-Grade Elementary School Students' Conceptions and Misconceptions about the Fungus Kingdom". Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "Common Student Ideas about Plants and Animals" (PDF). Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- S2CID 648881.

- PMID 8265589.

- ^ Deacon 2005, p. 4.

- ^ a b Deacon 2005, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 28–33.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 31–32.

- PMID 16874107.

- ^ Deacon 2005, p. 58.

- PMID 10714900.

- S2CID 22370361.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 685.

- ^ a b c Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 30.

- from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 33.

- ^ S2CID 5026076.

- PMID 16279413.

- ^ S2CID 23537608.

- S2CID 23358348.

- S2CID 11191347.

- PMID 18343697.

- ^ PMID 17520016.

- .

- S2CID 4121180.

- S2CID 211266075.

- PMID 33228036.

- ^ "Fungi in Mulches and Composts". University of Massachusetts Amherst. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- S2CID 23827807.

- S2CID 240568551.

- ^ a b Kirk et al. 2008, p. 489.

- ^ S2CID 4686378. Archived from the original(PDF) on 26 March 2009.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-4580-6.

- .

- ^ Ainsworth 1976, p. 1.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Ainsworth 1976, p. 18.

- PMID 17196017.

- from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Deacon 2005, p. 51.

- ^ Deacon 2005, p. 57.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-1043-0.

- PMID 32132107.

- S2CID 5432120.

- PMID 16151185.

- ^ Hanson 2008, pp. 127–141.

- doi:10.1139/x03-065. Archivedfrom the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 204–205.

- ISBN 978-0-521-30899-1.

- PMID 12208998.

- ^ PMID 1837147.

- ISBN 978-0-7923-4981-5.

- S2CID 7111935.

- PMID 17576216.

- S2CID 1356254.

- PMID 3939987.

- S2CID 205365895.

- PMID 17919950.

- PMID 12325127.

- S2CID 39155292.

- PMID 16628217.

- PMID 25506342.

- S2CID 45815733.

- PMID 18848901.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 48–56.

- ^ Kirk et al. 2008, p. 633.

- S2CID 2898102.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-0067-6.

- ISBN 978-0-89054-400-6.

- ^ from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- PMID 10398676.

- ^ S2CID 2551424.

- S2CID 10818930.

- ^ Jennings & Lysek 1996, pp. 107–114.

- ^ Deacon 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 492–493.

- ^ Jennings & Lysek 1996, p. 142.

- ^ Deacon 2005, pp. 21–24.

- ^ a b "Spore Dispersal in Fungi". botany.hawaii.edu. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ "Dispersal". herbarium.usu.edu. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- PMID 26509436.

- PMID 30804195.

- PMID 16219510.

- PMID 17784861.

- from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Kirk et al. 2008, p. 495.

- ^ "Stipitate hydnoid fungi, Hampshire Biodiversity Partnership" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-8020-5307-7.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 545.

- PMID 22091779.

- PMID 10318929.

- PMID 29463658.

- PMID 26834823.

- ^ Jennings & Lysek 1996, pp. 114–115.

- PMID 1537549.

- S2CID 25879264.

- ISBN 978-0-19-517234-8.

- ^ Taylor & Taylor 1993, p. 19.

- ^ Taylor & Taylor 1993, pp. 7–12.

- from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- S2CID 6689439.

- ^ First mushrooms appeared earlier than previously thought

- ^ S2CID 4302864.

- ^ Taylor & Taylor 1993, pp. 84–94 & 106–107.

- PMID 20525580.

- ^ Zimmer C (22 May 2019). "How Did Life Arrive on Land? A Billion-Year-Old Fungus May Hold Clues – A cache of microscopic fossils from the Arctic hints that fungi reached land long before plants". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- S2CID 162180486.

- ^ Timmer J (22 May 2019). "Billion-year-old fossils may be early fungus". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- PMID 33510166.

- ^ PMID 33873429.

- S2CID 43553633.

- .

- S2CID 1746303.

- from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Blackwell M, Vilgalys R, James TY, Taylor JW (2009). "Fungi. Eumycota: mushrooms, sac fungi, yeast, molds, rusts, smuts, etc". Tree of Life Web Project. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- PMID 23110612.

- from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- S2CID 4346359.

- S2CID 22011469.

- S2CID 58937537.

- doi:10.2113/0260035.

- .

- PMID 11427710.

See image 2

- S2CID 46198018.

- PMID 22916007.

That ecological calamity was accompanied by massive deforestation, an event followed by a fungal bloom, as the earth became a massive compost.

- ^ PMID 18461162.

- ^ PMID 33607033.

- ^ "Palaeos Fungi: Fungi". Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. for an introduction to fungal taxonomy, including controversies. archive

- S2CID 23123595.

- PMID 25083410.

- ^ Redhead S, Norvell L (2013). "MycoBank, Index Fungorum, and Fungal Names recommended as official nomenclatural repositories for 2013". IMA Fungus. 3 (2): 44–45.

- ISBN 978-2-9555841-0-1. Archivedfrom the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- S2CID 46141350.

- .

- ^ PMID 31659870.

- PMID 28944750.

- from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- PMID 16885325.

- ^ PMID 11607500.

- S2CID 82128210.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 145.

- PMID 31739583.

- PMID 18943925.

- PMID 24086046.

- S2CID 59307118.

- PMID 32850475.

- PMID 16696642.

- ISBN 978-0-12-805089-7.

- ISBN 978-0-12-509551-8.

- ISBN 9781466578739.

- ^ "An Introduction to Soil Biology". Humankind Oregon.

- PMID 17307120.

- ^ PMID 17244056.

- PMID 15911555.

- ^ PMID 17148364.

- PMID 10742053.

- PMID 9447662.

- PMID 14671327.

- ^ PMID 16713732.

- ^ PMID 15288621.

- S2CID 12377410.

- S2CID 17048094.

- S2CID 133399719.

- PMID 16843567.

- ^ Yong E (14 April 2016). "Trees Have Their Own Internet". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- PMID 19767309.

- S2CID 23182632.

- S2CID 23909652.

- ISBN 978-0-300-08249-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7167-1007-3.

- ^ Deacon 2005, p. 267.

- ISBN 978-1-56098-879-3.

- ^ Kirk et al. 2008, p. 378.

- ^ Deacon 2005, pp. 267–276.

- PMID 28298352.

- S2CID 233200379.

- ^ Deacon 2005, p. 277.

- ^ "Entomologists: Brazilian Stingless Bee Must Cultivate Special Type of Fungus to Survive". Sci-News.com. 23 October 2015. Archived from the original on 25 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- from the original on 7 May 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-75937-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-75936-4.

- PMC 4931425.

- S2CID 82107953.

- PMID 29395728.

- PMID 31133880.

- PMID 28142223.

- PMID 17494736.

- PMID 21848815.

- ^ "Asterotremella gen. nov. albida, an anamorphic tremelloid yeast isolated from the agarics Asterophora lycoperdoides and Asterophora parasitica". Retrieved 19 April 2019 – via ResearchGate.

- PMID 17352904.

- PMID 16375671.

- PMID 17223625.

- PMID 17487271.

- ISBN 978-1-4160-4470-3.

- PMID 17709917.

- PMID 33330142.

- PMID 19161358.

- PMID 4628853.

- PMID 35425630.

- ^ ELBEIN S (6 June 2023). "Fungi may offer 'jaw-dropping' solution to climate change". The Hill. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Fungi stores a third of carbon from fossil fuel emissions and could be essential to reaching net zero, new study reveals". EurekAlert. UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- PMID 17133714.

- PMID 33142955.

- PMID 11036689.

- PMID 17686752.

- PMID 17616735.

- PMID 16382157.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ PMID 16087747.

- ^ S2CID 52857557.

- PMID 2651864.

- S2CID 73501127.

- S2CID 2222358.

- S2CID 215411291.

- S2CID 221522085.

- ^ "Plant-based meat substitutes - products with future potential | Bioökonomie.de". biooekonomie.de. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Berlin KC, biotechnology ic, Artists HC, Artists H (28 January 2022). "Mushroom meat substitutes: A brief patent overview". On Biology. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- PMID 25734035.

- PMID 32973216.

- PMID 15719552.

- PMID 18221183.

- PMID 18373943.

- PMID 17249298.

- S2CID 5761188.

- S2CID 248099554.

- PMID 9862140.

- PMID 18547117.

- ^ S2CID 3866471.

- S2CID 29723996.

- ISBN 978-0-87131-981-4.

- PMID 25784670.

- PMID 18317543.

- S2CID 211071754.

- S2CID 21741034.

- ISBN 978-0-8247-8294-8.

- PMID 16499989.

- S2CID 36874528.

- PMID 8267862.

- PMID 18095455.

- S2CID 23049409.

- ISBN 978-1-58008-175-7.

- ^ Hall 2003, pp. 13–26.

- PMID 21770.

- PMID 12810273.

- ISBN 978-0-520-03656-7.

- PMID 9604278.

- PMID 17391587.

- PMID 14505933.

- S2CID 41451034.

- ^ Hall 2003, p. 7.

- ISBN 978-0-295-96480-5.

- PMID 16223517.

- ^ Becker H (1998). "Setting the Stage To Screen Biocontrol Fungi". United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-12-803527-6.

- PMID 10524330.

- S2CID 14460348.

- PMID 25756954.

- doi:10.2134/agronj2002.5670. Archived from the originalon 21 July 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- PMID 12772860.

- S2CID 232230208.

- ^ "Fungi to fight 'toxic war zones'". BBC News. 5 May 2008. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- PMID 17564604.

- S2CID 52805144.

- PMID 16588492.

- PMID 2700541.

- PMID 15846337.

- PMID 32057111.

- ISBN 978-0-521-43980-0.

- PMID 18571355.

- S2CID 4830678.

- ^ "Trichoderma spp., including T. harzianum, T. viride, T. koningii, T. hamatum and other spp. Deuteromycetes, Moniliales (asexual classification system)". Biological Control: A Guide to Natural Enemies in North America. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- S2CID 22956.

Cited literature

- Ainsworth GC (1976). Introduction to the History of Mycology. Cambridge, UK: ISBN 978-0-521-11295-6.

- Alexopoulos CJ, Mims CW, Blackwell M (1996). Introductory Mycology. ISBN 978-0-471-52229-4.

- Deacon J (2005). Fungal Biology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: ISBN 978-1-4051-3066-0.

- Hall IR (2003). Edible and Poisonous Mushrooms of the World. Portland, Oregon: ISBN 978-0-88192-586-9.

- Hanson JR (2008). The Chemistry of Fungi. ISBN 978-0-85404-136-7.

- Jennings DH, Lysek G (1996). Fungal Biology: Understanding the Fungal Lifestyle. Guildford, UK: Bios Scientific Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85996-150-6.

- Kirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi (10th ed.). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. ISBN 978-0-85199-826-8.

- Taylor EL, Taylor TN (1993). The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: ISBN 978-0-13-651589-0.

Further reading

- Kolbert, Elizabeth, "Spored to Death" (review of Emily Monosson, Blight: Fungi and the Coming Pandemic, Norton, 253 pp.; and Alison Pouliot, Meetings with Remarkable Mushrooms: Forays with Fungi Across Hemispheres, University of Chicago Press, 278 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXX, no.14 (21 September 2023), pp. 41–42. "Fungi sicken us and fungi sustain us. In either case, we ignore them at our peril." (p. 42.)