Gaelic warfare

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (April 2010) |

Gaelic warfare was the type of

), in the pre-modern period.| Part of a series on |

| War |

|---|

Indigenous Gaelic warfare

Weaponry

Irish warfare was for centuries centered on the Ceithearn, or

"... A kind of footman, slightly armed with a sword, a target (round shield) of wood, or a bow and sheaf of arrows with barbed heads, or else three darts, which they cast with a wonderful facility and nearness..."[1]

For centuries the backbone of any Gaelic Irish army were these lightly armed foot soldiers. Ceithearn were usually armed with a spear (gae) or sword (claideamh), long dagger (scian),[2] bow (bogha) and a set of javelins, or darts (gá-ín).[3]

The use of

These adaptations and developments brought regular use of other weapons such as

. Many of the medieval swords found in Ireland today are unlikely to be of native manufacture given many of the pommels and cross-guard decoration is not of Gaelic origin.[4]

By the time of

Aside from

Gaelic Warfare was anything but stagnant and was adaptive and ever changing. By the time of the

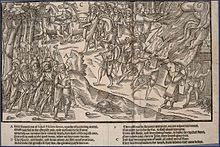

Gaelic raid culture

The Gaelic Irish preferred hit-and-run tactics and shock tactics like ambushes and raids (the crech), which involved catching the enemy unaware. One of the most common causes of conflict in Gaelic Ireland was cattle raiding. Cattle were the main form of wealth in Gaelic Ireland, as it was in many parts of Europe, as currency had not yet been introduced, and the aim of most wars was the capture of the enemy's cattle. If this worked, the raiders would then seize any valuables (mainly livestock) and potentially valuable hostages, burn the crops, and escape.[10]

Indeed,

The cattle raid was often called a as important examples. Gaelic warfare was

or bought the newest and most effective weaponry. Although hit-and-run raiding was the preferred Gaelic tactic inEspecially

Armour

It's often stated that for the most part, the Gaelic Irish fought without armour, instead wearing saffron coloured belted

Customs

Before the

The spirit and traditions of single combat would live on and manifest itself in other ways in Modern Gaelic cultures. In

Urban defense

Many of the towns in Gaelic Ireland had some type of defense in the form of walls or ditches. For most of the Gaelic period, dwellings and buildings were

Following the

By the 12th century, "some mottes, especially in frontier areas, had almost certainly been built by the Gaelic Irish in imitation" of the Normans.[20] The

Starting in the late 16th century, an era of

At both the

Tactics and organisation

Initially Kern or ceithern were members of individual tribes, but later, when the Vikings and English came to Ireland, they introduced new systems of billeting soldiers, the kern became billeted soldiers and mercenaries who served the highest bidder. Because Kern were equipped and trained as light skirmishers, they faced a severe disadvantage in pitched battle. In battle, the kern and lightly armed horsemen would charge the enemy line after intimidating them with shock tactics, war cries, horns and pipes.[27]

If the kern failed to break an enemy line after the charge, they were liable to flee. If the enemy formation did not break under the kern's charge, then heavily armed and armoured Irish soldiers were moved forward and would advance from the rear lines and attack, these units were replaced in the late 13th century by the

By the time of

Adaptations

As time went on, the Gaels

The Dál Riata, for example, after colonizing the west of Scotland and becoming a maritime power, became an army composed completely of archers. Slings also went out of use, replaced by both bows and a very effective naval weapon called the crann tabhaill, a kind of catapult.

Later, when the

Heavier hacking-swords and

The

During the

The Scottish rebels

- "They were all on foot; picked men they were, enthusiastic, armed with keen axes, and other weapons, and with their shields closely locked in front of them, they formed an impenetrable phalanx ..."[29]

- "They had axes at their sides and lances in their hands. They advanced like a thick-set hedge and such a phalanx could not easily be broken."[30]

In early engagements, like when Schiltrons were used by

Standards and music

Many Gaelic clans each had their own distinct

Exported Gaelic warfare

Gallowglass

The most prolific

One of the first battles believed to have to included Gallowglass was the

Gallowglasses were frequently hired and served as

Despite the increased usage of

Hobelars

Early Hobelars wore little armour, they typically rode on smaller quicker unarmoured

During his

Hobelars were highly proficient atAfter the successful and effective deployment of these horsemen by both the English and Scottish during the

In Scotland, Hobelars served as the offensive arm of castle garrisons. Hobelars were utilized as raiders across the border by both the English and Scots, they can be viewed as early predecessors to the reivers and moss-troopers of the Scottish borderlands.[44]

Later Weaponry

During the

Redshanks

The redshanks were usually armed alike, principally with

Later in the period, they may have adopted the

By the mid-17th century, a large number of

The subsequent

List of Gaelic conflicts and battles

This is a list of battles or conflicts in which the Gaels had a leading or crucial role.

- 106 CE : Magh Line

- 157 CE : Battle of Tuath Amrois

- 195 CE : Battle of Maigh Mucruimhe

- 225 CE : Battle of Crinna

- 283 CE : Cath Gabhra

- 331 CE : Achaidh Leithdeircc

- 493 CE : Battle for the Body of St. Patrick

- 596 CE : Battle of Raith

- 561 CE : Battle of Cúl Dreimhne

- 603 CE : Battle of Degsastan

- 629 CE : Battle of Fid Eoin

- 637 CE : Battle of Moira

- 735 CE : Óengus campaigns against Dál Riata

- 736 CE : Battle of Cnoc Coirpi

- 741 CE : Battle of Druimm Cathmail

- 841 CE : MacAlpin's treason

- 795 CE : Early Viking raids in Ireland

- 868 CE: Battle of Cell Ua nDaigri

- 877 CE : Battle of Strangford Lough

- 908 CE : Battle of Ballaghmoon

- 915 CE : Battle of Confey

- 917 CE : Battle of Mag Femen

- 919 CE : Battle of Islandbridge

- 968 CE : Battle of Sulcoit

- 968 CE : Burning of Luimnech

- 977 CE : Battle of Cathair Cuan

- 978 CE : Battle of Belach Lechta

- 980 CE : Battle of Tara

- 999 CE : Battle of Glenmama

- 1014 CE : Battle of Clontarf

- 1130 CE : Battle of Stracathro

- 1132 CE : O'Brian's Siege of Galway

- 1149 CE : O'Brian's second Siege of Galway

- 1151 CE : Battle of Móin Mhór

- 1164 CE : Battle of Renfrew

- 1169 CE : Siege of Wexford

- 1171 CE : Siege of Dublin

- 1174 CE : Battle of Thurles

- 1185 CE : Prince John's Expedition

- 1230 CE : De Burgh's siege of Galway

- 1234 CE : Battle of the Curragh

- 1245 CE : Battle of Embo

- 1247 CE : Battle of Ballyshannon

- 1247 CE : Sack of Dun Gallimhe

- 1249 CE : First Battle of Athenry

- 1256 CE : Battle of Magh Slecht

- 1257 CE : Battle of Creadran Cille

- 1260 CE : Battle of Down

- 1261 CE : Battle of Callann

- 1262 CE : Battle of Tooreencormick

- 1263 CE : Battle of Largs

- 1270 CE : Battle of Connacht

- 1275 CE : Manx revolt

- 1275 CE : Battle of Ronaldsway

- 1294 CE : Battle of Red Ford

- 1296 CE : Sack of Berwick

- 1297 CE : Lanark

- 1297 CE : Raid on Scone

- 1297 CE : Battle of Stirling Bridge

- 1298 CE : Battle of Falkirk

- 1303 CE : Battle of Roslin

- 1304 CE : Battle of Happrew

- 1304 CE : Siege at Stirling Castle

- 1304 CE : Earnside

- 1306 CE : Battle of Dalrigh

- 1307 CE : Battle of Loch Ryan

- 1307 CE : Battle of Turnberry

- 1307 CE : Battle of Glen Trool

- 1307 CE : Battle of Loudoun Hill

- 1307 CE : Battle of Slioch

- 1308 CE : Battle of Barra

- 1308 CE : Harrying of Buchan

- 1308 CE : Battle of the River Dee

- 1308 CE : Battle of the Pass of Brander

- 1314 CE : Capture of Roxburgh

- 1314 CE : Battle of Bannockburn

- 1315 CE : Battle of Moiry Pass

- 1315 CE : Battle of Connor

- 1315 CE : Battle of Kells

- 1316 CE : Battle of Skerries

- 1316 CE : Second Battle of Athenry

- 1317 CE : Battle of Lough Raska

- 1318 CE : Battle of Dysert O'Dea

- 1318 CE : Battle of Faughart

- 1327 CE : Battle of Fiodh-an-Átha

- 1328 CE : Battle of Thomond

- 1329 CE : Braganstown massacre

- 1329 CE : Battle of Ardnocher

- 1337 CE : Battle of Drumlui

- 1370 CE : Battle of Invernahavon

- 1385 CE : Battle of Tochar Cruachain-Bri-Ele

- 1391 CE : Raid of Angus

- 1394 CE : Battle of Ros-Mhic-Thriúin

- 1396 CE : Battle of the North Inch

- 1399 CE : Battle of Tragh-Bhaile

- 1402 CE : Battle of Drumoak

- 1406 CE : Battle of Cluain Immorrais

- 1406 CE : Battle of Tuiteam Tarbhach

- 1411 CE : Battle of Dingwall

- 1411 CE : Battle of Harlaw

- 1426 CE : Battle of Harpsdale

- 1429 CE : Battle of Lochaber

- 1429 CE : Battle of Mamsha

- 1429 CE : Battle of Palm Sunday

- 1429 CE : Siege of Inverness

- 1430 CE : Battle of Drumnacoub

- 1431 CE : Battle of Inverlochy

- 1437 CE : Sandside Chase

- 1438 CE : Battle of Tannach

- 1439 CE : Battle of Craignaught Hill

- 1441 CE : Battle of Craig Cailloch

- 1445 CE : Battle of Arbroath

- 1452 CE : Battle of Bealach nam Broig

- 1452 CE : Battle of Brechin

- 1454 CE : Battle of Clachnaharry

- 1455 CE : Battle of Arkinholm

- 1470 CE : Battle of Corpach

- 1478 CE : Battle of Champions

- 1480 CE : Battle of Bloody Bay

- 1480 CE : Battle of Lagabraad

- 1480 CE : Battle of Skibo and Strathfleet

- 1485 CE : Battle of Blar Na Pairce

- 1486 CE : Battle of Tarbat

- 1487 CE : Battle of Aldy Charrish

- 1490 CE : Massacre of Monzievaird

- 1491 CE : Battle of Blar Na Pairce

- 1491 CE : Raid on Ross

- 1497 CE : Battle of Drumchatt

- 1499 CE : Battle of Daltullich

- 1501 CE : Dubh's Rebellion

- 1504 CE : Battle of Knockdoe

- 1504 CE : Cairnburgh Castle

- 1505 CE : Achnashellach

- 1513 CE : Battle of Glendale

- 1522 CE : Battle of Knockavoe

- 1534 CE : Kildare rebellion

- 1539 CE : Battle of Belahoe

- 1544 CE : Battle of the Shirts

- 1544 CE : Raids of Urquhart

- 1559 CE : Battle of Spancel Hill

- 1569 CE : First Desmond Rebellion

- 1565 CE : Battle of Glentaisie

- 1567 CE : Battle of Farsetmore

- 1570 CE : Battle of Bun Garbhain

- 1570 CE : Battle of Torran-Roy

- 1572 CE : Sack of Athenry

- 1574 CE : Clandeboye massacre

- 1575 CE : Rathlin Island massacre

- 1577 CE : Sack of Eigg

- 1577 CE : Massacre of Mullaghmast

- 1578 CE : Battle of the Spoiling Dyke

- 1579 CE : Second Desmond Rebellion

- 1580 CE : Battle of Glenmalure

- 1580 CE : Siege of Carrigafoyle Castle

- 1580 CE : Siege of Smerwick

- 1585 CE : Battle of the Western Isles

- 1590 CE : Battle of Doire Leathan

- 1590 CE : Battle of Clynetradwell

- 1593 CE : Battle of Belleek

- 1594 CE : Siege of Enniskillen

- 1594 CE : Battle of the Ford of the Biscuits

- 1594 CE : Battle of Glenlivet

- 1595 CE : Assault on the Blackwater Fort

- 1595 CE : Battle of Clontibret

- 1596 CE : O'Donnell's Siege of Galway

- 1597 CE : Dublin gunpowder explosion

- 1597 CE : Battle of Carrickfergus

- 1598 CE : Battle of Traigh Ghruinneart

- 1598 CE : Battle of Benbigrie

- 1598 CE : Battle of the Yellow Ford

- 1599 CE : Battle of Deputy's Pass

- 1599 CE : Siege of Cahir Castle

- 1600 CE : Battle of Curlew Pass

- 1600 CE : Battle of Moyry Pass

- 1600 CE : Battle of Lifford

- 1601 CE : Battle of Carinish

- 1601 CE : Battle of Coire Na Creiche

- 1601 CE : Siege of Donegal

- 1601 CE : Siege of Kinsale

- 1601 CE : Battle of Castlehaven

- 1602 CE : Siege of Dunboy

- 1602 CE : Dursey massacre

- 1602 CE : Burning of Dungannon

- 1641 CE : Irish Rebellion of 1641

- 1641 CE : Portadown massacre

- 1641 CE : Siege of Drogheda

- 1641 CE : Battle of Julianstown

- 1642 CE : Battle of Kilrush

- 1642 CE : Rathlin Island Massacre

- 1645 CE : Battle of the Braes of Strathdearn

- 1645 CE : Battle of Inverlochy

- 1646 CE : Battle of Benburb

- 1646 CE : Battle of Lagganmore

- 1646 CE : Dunoon massacre

- 1646 CE : Battle of Rhunahaorine Moss

- 1647 CE : Sack of Cashel

- 1647 CE : Battle of Dunaverty

- 1649 CE : Drogheda Massacre

- 1650 CE : Siege of Clonmel

- 1650 CE : Siege of Charlemont

- 1655 CE : Stand-off at the Fords of Arkaig

- 1680 CE : Battle of Altimarlach

- 1688 CE : Battle of Mulroy

- 1692 CE : Massacre of Glencoe

- 1715 CE : Siege of Brahan

- 1715 CE : Battle of Sheriffmuir

- 1719 CE : Capture of Eilean Donan Castle

- 1719 CE : Battle of Glen Shiel

- 1721 CE : Battle of Glen Affric

- 1721 CE : Battle of Coille Bhan

- 1745 CE : Highbridge Skirmish

- 1745 CE : First Siege of Ruthven Barracks

- 1745 CE : Battle of Prestonpans

- 1745 CE : Siege of Culloden House

- 1745 CE : First Siege of Carlisle

- 1745 CE : Clifton Moor Skirmish

- 1745 CE : Second Siege of Carlisle

- 1745 CE : First Siege of Fort Augustus

- 1745 CE : Battle of Inverurie

- 1746 CE : Battle of Falkirk Muir

- 1746 CE : Siege of Stirling Castle

- 1746 CE : Second Siege of Ruthven Barracks

- 1746 CE : Siege of Inverness

- 1746 CE : Second Siege of Fort Augustus

- 1746 CE : Atholl raids

- 1746 CE : Siege of Blair Castle

- 1746 CE : Skirmish of Keith

- 1746 CE : Siege of Fort William

- 1746 CE : Battle of Dornoch

- 1746 CE : Skirmish of Tongue

- 1746 CE : Battle of Littleferry

- 1746 CE : Battle of Culloden

See also

- Gaels

- Gaelic Ireland

- Celtic warfare

- Ceithearn (Kern)

- Ceathairne (Cateran)

- Gallóglaigh (Gallowglass)

- Hobelar

- Fianna

- Redshank

- Military History

- Warfare in Medieval Scotland

Notes

- ^ Fergus Cannan, 'HAGS OF HELL': Late Medieval Irish Kern. History Ireland , Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 14–17

- ^ Sgian-dubh

- ^ 'HAGS OF HELL': Late Medieval Irish Kern. History Ireland , Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 17

- JSTOR 25506140.

- ^ Duffy, Seán, ed. (2005). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1-135-94824-5.

- ^ Ó Cléirigh, Cormac (1997). Irish frontier warfare: a fifteenth-century case study (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2010.

- ^ Flanagan, Marie Therese (1996). "Warfare in Twelfth-Century Ireland". A Military History of Ireland. Cambridge University Press. pp. 52–75.

- ^ G. A. Hayes-McCoy, "Strategy and Tactics in Irish Warfare, 1593–1601." Irish Historical Studies , Vol. 2, No. 7 (Mar. 1941), pp. 255

- ISBN 0-521-02014-X

- ^ Ó Cléirigh, Cormac (1997). Irish frontier warfare: a fifteenth-century case study (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2010.

- ^ Shae Clancy. "Cattle in Early Ireland". Celtic Well. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ The Topography of Ireland by Giraldus Cambrensis Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine (English translation)

- ^ Joyce, Patrick Weston (1906). "Chapter XVI: The House, Construction, Shape, and Size". A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland. Library Ireland. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Connolly, Sean J (2007). "Chapter 2: Late Medieval Ireland: The Irish". Contested island: Ireland 1460–1630. Oxford University Press. pp. 20–24.

- ^ Connolly, Sean J (2007). "Chapter 2: Late Medieval Ireland: The Irish". Contested island: Ireland 1460–1630. Oxford University Press. pp. 20–24.

- ^ O'Keeffe, Tadhg (1995). Rural settlement and cultural identity in Gaelic Ireland (PDF). Ruralia 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ Glasscock, Robin Edgar (2008) [1987]. "Chapter 8: Land and people, c.1300". In Cosgrove, Art (ed.). A New History of Ireland, Volume II: Medieval Ireland 1169–1534. Oxford University Press. pp. 205–239. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199539703.003.0009.

- ^ O'Keeffe, Tadhg (1995). Rural settlement and cultural identity in Gaelic Ireland (PDF). Ruralia 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ McKeon, Jim (2011). "Urban Defences in Anglo-Norman Ireland: Evidence from South Connacht". Eolas: The Journal of the American Society of Irish Medieval Studies. 5: 146–190. JSTOR 41585270.

- ^ Glasscock, Robin Edgar (2008) [1987]. "Chapter 8: Land and people, c.1300". In Cosgrove, Art (ed.). A New History of Ireland, Volume II: Medieval Ireland 1169–1534. Oxford University Press. pp. 205–239. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199539703.003.0009.

- ^ Glasscock, Robin Edgar (2008) [1987]. "Chapter 8: Land and people, c.1300". In Cosgrove, Art (ed.). A New History of Ireland, Volume II: Medieval Ireland 1169–1534. Oxford University Press. pp. 205–239. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199539703.003.0009.

- ^ Joyce, Patrick Weston (1906). "Chapter XVI: The House, Construction, Shape, and Size". A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland. Library Ireland. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Plant, David (28 February 2008). "The Siege of Clonmel, 1650". BCW Project. David Plant. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Manning, Roger (2000). An Apprenticeship in Arms: The Origins of the British Army 1585-1702. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Wheeler, James Scott (1999). Cromwell in Ireland. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 0-7171-2884-9.

- ^ "Clonmel: Its Monastery, and Siege by Cromwell". Duffy's Hibernian Magazine. III (14). August 1861. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Fergus Cannan, 'HAGS OF HELL': Late Medieval Irish Kern. History Ireland , Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 17

- ^ G. A. Hayes-McCoy, "Strategy and Tactics in Irish Warfare, 1593–1601." Irish Historical Studies , Vol. 2, No. 7 (Mar. 1941), pp. 255

- ^ Trokelowe, quoted in Brown, op.cit, p. 90

- ^ Vita Edwardi Secundi, quoted in Brown, Chris (2008). Bannockburn 1314. Stroud: History press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7524-4600-4.

- ISBN 9781906566241.

- ISBN 9781906566241.

- ^ Halpin; Newman (2006) p. 244; Simms (1998) p. 78; Simms (1997) pp. 111 fig. 5.3, 114 fig. 5.6; Halpin (1986) p. 205; Crawford, HS (1924).

- ^ Halpin; Newman (2006) p. 244; Verstraten (2002) p. 11; Crawford, HS (1924).

- ^ Ó Cléirigh, Cormac (1997). Irish frontier warfare: a fifteenth-century case study (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2010.

- ^ Duffy. The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. 2007 p. 1.

- ^ Ó Cléirigh, Cormac (1997). Irish frontier warfare: a fifteenth-century case study (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2010.

- ^ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Page 267-268, Hobelars

- ^ Hyland (1998), p 32, 14, 37

- ^ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Page 267-268,Hobelars

- ^ Hyland (1998), p 32, 14, 37

- ^ Lydon (1954)

- ^ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Page 267-268, Hobelars

- ^ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology, Volume 1, Page 267-268, Hobelars

- ^ Falls, Elizabeth's Irish Wars, p.79

- ^ Fforde, The Great Glen, 2011

- ^ Stevenson, Alasdair MacColla and the Highland Problem in the Seventeenth Century, 1980, p.83

- ^ Stevenson, Scottish Covenanters and Irish Confederates, 1981, p.4

- ^ Hill, James Michael, Celtic warfare, 1595–1763 (2003),J. Donald

- ^ Carlton, Charles (2002). Going to the Wars: The Experience of the British Civil Wars 1638–1651. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-84935-2., page 135

References

- G. A. Hayes-McCoy, "Strategy and Tactics in Irish Warfare, 1593–1601". Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 7 (Mar. 1941), pp. 255–279

- Fergus Cannan, "'HAGS OF HELL': late medieval Irish kern". History Ireland, Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 14–17

- The Barbarians, Terry Jones

- Julius Caesar, "De Bello Gallico"

- "Tain Bo Cuailnge", From the Book of Leinster

- Geoffrey Keating, "History of Ireland"

- "The Wars of the Gaels with the Foreigners"

- http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_armies_irish.html

- http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_armies_scots.html