Gallium scan

| Gallium-67 scan | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Gallium imaging |

| ICD-10-PCS | C?1?LZZ (planar) C?2?LZZ (tomographic) |

| ICD-9-CM | 92.18 |

| OPS-301 code | 3-70c |

| MedlinePlus | 003450 |

A gallium scan is a type of

Gallium salts are taken up by tumors, inflammation, and both acute and chronic infection,[3][4] allowing these pathological processes to be imaged. Gallium is particularly useful in imaging osteomyelitis that involves the spine, and in imaging older and chronic infections that may be the cause of a fever of unknown origin.[5][6]

Gallium-68 DOTA scans are increasingly replacing octreotide scans (a type of

Gallium citrate scan

In the past, the gallium scan was the

infections, and it still sometimes locates unsuspected tumors as it is taken up by many kinds of cancer cells in amounts that exceed those of normal tissues. Thus, an increased uptake of gallium-67 may indicate a new or old infection, an inflammatory focus from any cause, or a cancerous tumor.It has been suggested that gallium imaging may become an obsolete technique, with

In infections, the gallium scan has an advantage over indium leukocyte imaging in imaging

Mechanism

The body generally handles Ga3+ as though it were

Lactoferrin is contained within leukocytes. Gallium may bind to lactoferrin and be transported to sites of inflammation, or binds to lactoferrin released during bacterial

Common indications

- Whole-body survey to localize source of fever in patients with fever of unknown origin.[20]

- Detection of immunocompromised patient.[21]

- Evaluation and follow-up of active lymphocytic or

- Diagnosing vertebral osteomyelitis and/or disk space infection where gallium-67 is preferred over labeled leukocytes.

- Diagnosis and follow-up of medical treatment of retroperitoneal fibrosis.

- Evaluation and follow-up of drug-induced pulmonary toxicity (e.g. Bleomycin, Amiodarone)

- Evaluation of patients who are not candidates for WBC scans (WBC count less than 6,000).

Note that all of these conditions are also seen in PET scans using the gallium-68.

Technique

The main (67Ga) technique uses

A common injection dose is around 150 megabecquerels.[25] Imaging should not usually be sooner than 24 hours as high background at this time produces false negatives. Forty-eight-hour whole body images are appropriate. Delayed imaging can be obtained even 1 week or longer after injection if bowel is confounding. SPECT can be performed as needed. Oral laxatives or enemas can be given before imaging to reduce bowel activity and reduce dose to large bowel; however, the usefulness of bowel preparation is controversial.[24]

10% to 25% of the dose of gallium-67 is excreted within 24 hours after injection (the majority of which is excreted through the kidneys). After 24 hours the principal excretory pathway is colon.[24] The "target organ" (organ that receives the largest radiation dose in the average scan) is the colon (large bowel).[23]

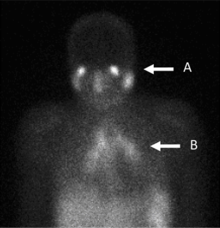

In a normal scan, uptake of gallium is seen in wide range of locations which do not indicate a positive finding. These typically include soft tissues,

Gallium PSMA scan

The positron emitting isotope, 68Ga, can be used to target

In December 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 68Ga PSMA-11 for medical use in the United States.[28][29] It is indicated for positron emission tomography (PET) of prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) positive lesions in men with prostate cancer.[30][29] It is manufactured by the UCLA Biomedical Cyclotron Facility.[29] The FDA approved 68Ga PSMA-11 based on evidence from two clinical trials (Trial 1/NCT0336847 identical to NCT02919111 and Trial 2/NCT02940262 identical to NCT02918357) of male participants with prostate cancer.[29] Some participants were recently diagnosed with the prostate cancer.[29] Other participants were treated before, but there was suspicion that the cancer was spreading because of rising prostate specific antigen or PSA.[29] The trials were conducted at two sites in the United States.[29]

The FDA considers 68Ga PSMA-11 to be a first-in-class medication.[31]

Common indications

Gallium PSMA scanning is recommended primarily in cases of biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer, particularly for patients with low PSA values, and in patients with high risk disease where metastases are considered likely.[32][33]

Technique

An

Gallium DOTA scans

68Ga

In June 2016, Netspot (kit for the preparation of gallium Ga-68 dotatate injection) was approved for medical use in the United States.[39][40]

In August 2019, 68Ga edotreotide injection (68Ga DOTATOC) was approved for medical use in the United States for use with PET imaging for the localization of somatostatin receptor positive neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in adults and children.[41][42][43]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 68Ga edotreotide (DOTATOC) based on evidence from three clinical trials (Trial 1/NCT#1619865, Trial 2/NCT#1869725, Trial 3/NCT#2441062) of 334 known or suspected neuro-endocrine tumors.[42] The trials were conducted in the United States.[42]

Gallium (68Ga) oxodotreotide was approved for medical use in Canada as Netspot in July 2019,[44] and as Netvision in May 2022.[45]

Radiochemistry of gallium-67

Gallium-67 citrate is produced by a cyclotron. Charged particle bombardment of enriched Zn-68 is used to produce gallium-67. The gallium-67 is then complexed with citric acid to form gallium citrate. The half-life of gallium-67 is 78 hours.

Radiochemistry of gallium-68

References

- ISBN 9781461495512.

- ISBN 9783319545929. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- ^ Verberne SJ and O. P. P. Temmerman (2017). 12 - Imaging of prosthetic joint infections Archived 2022-02-21 at the Wayback Machine - Arts, J.J. Chris. Management of Periprosthetic Joint Infections (PJIs). J. Geurts, Woodhead Publishing: 259-285.

- S2CID 9202184. Archived from the originalon 2016-12-16. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- S2CID 26280068.

- S2CID 19293222.

- S2CID 21843609.

- PMID 30096273.

- ISBN 9780521747622. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-02-21. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- PMID 21680576.

- ISBN 978-0323112925.

- PMID 8023169.

- ISBN 9780781779821.

- from the original on 2016-11-07. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- PMID 3880816.

- ISBN 9780387224275.

- PMID 8940716.

- ISBN 978-3-540-28026-2.

- from the original on 2022-07-07. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- ^ "Gallium scan". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ "ACR–SPR Practice Parameter for the Performance of Scintigraphy for Inflammation and Infection" (PDF). American College of Radiology. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-10-16. Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- ^ "Lung gallium scan". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ a b Bombardieri, Emilio; Aktolun, Cumali; Baum, Richard P.; Bishof-Delaloye, Angelica; Buscombe, John; Chatal, Jean François; Maffioli, Lorenzo; Moncayo, Roy; Mortelmans, Luc; Reske, Sven N. (2 September 2003). "67Ga Scintigraphy Procedure Guidelines for Tumour Imaging" (PDF). EANM. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Society of Nuclear Medicine Procedure Guideline for Gallium Scintigraphy in Inflammation" (PDF). SNMMI. 2 June 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Notes for Guidance on the Clinical Administration of Radiopharmaceuticals and Use of Sealed Radioactive Sources" (PDF). Administration of Radioactive Substances Advisory Committee. January 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ISBN 978-3-642-02399-6.

- S2CID 2448922.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Gallium Ga 68 PSMA-11". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 16 December 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Drug Trials Snapshot: Ga 68 PSMA-11". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 December 2020. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "GALLIUM GA 68 PSMA-11 Labeling-Package Insert" (PDF). Drugs@FDA. University of California, Los Angeles. 17 November 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "New Drug Therapy Approvals 2020". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 31 December 2020. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ S2CID 5882407.

- PMID 26790588.

- S2CID 3902900.

- PMID 25143861.

- (PDF) from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- PMID 22388631.

- PMID 26384594.

- ^ "Netspot (kit for the preparation of gallium Ga 68 dotatate injection)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 June 2016. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- Lay summary in: "Summary Review: Application number: 208547Orig1s000" (PDF). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 30 May 2016.

- ^ "Netspot- 68ga-dotatate kit". DailyMed. 23 October 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "GA-68-DOTATOC- edotreotide gallium ga-68 injection, solution". DailyMed. 3 September 2019. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ a b c "Drug Trials Snapshots: Ga-68-DOTATOC". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 August 2019. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Gallium Dotatoc GA 68". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 23 September 2019. Archived from the original on 6 April 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Summary Basis of Decision (SBD) for Netspot". Health Canada. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Summary Basis of Decision - NETVision". Health Canada. 26 May 2022. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ISBN 9789201069085. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2017-03-09. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ ISBN 978-1870965873.

- ISBN 9789282222485. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2017-09-14.