Gemcitabine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /dʒɛmˈsaɪtəbiːn/ |

| Trade names | Gemzar, others[1] |

| Other names | 2', 2'-difluoro 2'deoxycytidine, dFdC |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | <10% |

| Elimination half-life | Short infusions: 32–94 minutes Long infusions: 245–638 minutes |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Gemcitabine, sold under the brand name Gemzar, among others,

Common side effects include

Gemcitabine was patented in 1983 and was approved for medical use in 1995.[6] Generic versions were introduced in Europe in 2009 and in the US in 2010.[7][8] It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines.[9]

Medical uses

Gemcitabine treats various

It is used off-label to treat cholangiocarcinoma[13] and other biliary tract cancers.[14]

Contraindications and interactions

Taking gemcitabine can also affect fertility in men and women, sex life, and menstruation. Women taking gemcitabine should not become pregnant, and pregnant and breastfeeding women should not take it.[15]

As of 2014, drug interactions had not been studied.[11][10]

Adverse effects

Gemcitabine is a chemotherapy drug that works by killing any cells that are dividing.[10] Cancer cells divide rapidly and so are targeted at higher rates by gemcitabine, but many essential cells also divide rapidly, including cells in skin, the scalp, the stomach lining, and bone marrow, resulting in adverse effects.[16]: 265

The gemcitabine label carries warnings that it can suppress bone marrow function and cause

More than 10% of users develop adverse effects, including difficulty breathing, low white and red blood cells counts, low platelet counts, vomiting and nausea, elevated transaminases, rashes and itchy skin, hair loss, blood and protein in urine, flu-like symptoms, and edema.[10][15]

Common adverse effects (occurring in 1–10% of users) include fever, loss of appetite, headache, difficulty sleeping, tiredness, cough, runny nose, diarrhea, mouth and lip sores, sweating, back pain, and muscle pain.[10]

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare but serious side effect that been associated with particular chemotherapy medications including gemcitabine. TTP is a blood disorder and can lead to microangipathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), neurologic abnormalities, fever, and renal disease.[18]

Pharmacology

Gemcitabine is

After being thrice

When gemcitabine is incorporated into DNA it allows a native, or normal, nucleoside base to be added next to it. This leads to "masked chain termination" because gemcitabine is a "faulty" base, but due to its neighboring native nucleoside it eludes the cell's normal repair system (

The form of gemcitabine with two phosphates attached (dFdCDP) also has activity; it inhibits the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), which is needed to create new DNA nucleotides. The lack of nucleotides drives the cell to uptake more of the components it needs to make nucleotides from outside the cell, which also increases uptake of gemcitabine.[2][19][20][22]

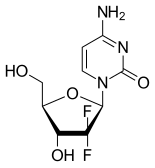

Chemistry

Gemcitabine is a synthetic pyrimidine nucleoside prodrug—a nucleoside analog in which the hydrogen atoms on the 2' carbon of deoxycytidine are replaced by fluorine atoms.[2][23][24]

The synthesis described and pictured below is the original synthesis done in the Eli Lilly Company labs. Synthesis begins with enantiopure D-glyceraldehyde (R)-2 as the starting material which can made from D-mannitol in 2–7 steps. Then fluorine is introduced by a "building block" approach using ethyl bromodifluoroacetate. Then, Reformatsky reaction under standard conditions will yield a 3:1 anti/syn diastereomeric mixture, with one major product. Separation of the diastereomers is carried out via HPLC, thus yielding the anti-3 gemcitabine in a 65% yield.[23][24] At least two other full synthesis methods have also been developed by different groups.[24]

History

Gemcitabine was first synthesized in Larry Hertel's lab at Eli Lilly and Company during the early 1980s. It was intended as an antiviral drug, but preclinical testing showed that it killed leukemia cells in vitro.[25]

During the early 1990s gemcitabine was studied in clinical trials. The pancreatic cancer trials found that gemcitabine increased one-year survival time significantly, and it was approved in the UK in 1995[10] and approved by the FDA in 1996 for pancreatic cancers.[4] In 1998, gemcitabine received FDA approval for treating non-small cell lung cancer and in 2004, it was approved for metastatic breast cancer.[4]

European labels were harmonized by the EMA in 2008.[26]

By 2008, Lilly's worldwide sales of gemcitabine were about $1.7 billion; at that time its US patents were set to expire in 2013 and its European patents in 2009.[27] The first generic launched in Europe in 2009,[7] and patent challenges were mounted in the US which led to invalidation of a key Lilly patent on its method to make the drug.[28][29] Generic companies started selling the drug in the US in 2010 when the patent on the chemical itself expired.[29][8] Patent litigation in China made headlines there and was resolved in 2010.[30]

Society and culture

As of 2017, gemcitabine was marketed under many brand names worldwide: Abine, Accogem, Acytabin, Antoril, axigem, Bendacitabin, Biogem, Boligem, Celzar, Citegin, Cytigem, Cytogem, Daplax, DBL, Demozar, Dercin, Emcitab, Enekamub, Eriogem, Fotinex, Gebina, Gemalata, Gembin, Gembine, Gembio, Gemcel, Gemcetin, Gemcibine, Gemcikal, Gemcipen, Gemcired, Gemcirena, Gemcit, Gemcitabin, Gemcitabina, Gemcitabine, Gemcitabinum, Gemcitan, Gemedac, Gemflor, Gemful, Gemita, Gemko, Gemliquid, Gemmis, Gemnil, Gempower, Gemsol, Gemstad, Gemstada, Gemtabine, Gemtavis, Gemtaz, Gemtero, Gemtra, Gemtro, Gemvic, Gemxit, Gemzar, Gentabim, Genuten, Genvir, Geroam, Gestredos, Getanosan, Getmisi, Gezt, Gitrabin, Gramagen, Haxanit, Jemta, Kalbezar, Medigem, Meditabine, Nabigem, Nallian, Oncogem, Oncoril, Pamigeno, Ribozar, Santabin, Sitagem, Symtabin, Yu Jie, Ze Fei, and Zefei.[1]

Research

Because it is clinically valuable and is only useful when delivered intravenously, methods to reformulate it so that it can be given by mouth have been a subject of research.[31][32][33]

Research into

It has been studied as a treatment for

References

- ^ a b c "Gemcitabine International Brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Gemcitabine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ "Drug Formulary/Drugs/ gemcitabine - Provider Monograph". Cancer Care Ontario. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ a b c "FDA Approval for Gemcitabine Hydrochloride". National Cancer Institute. 2006-10-05. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- PMID 33137361.

- ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ a b Myers C (13 March 2009). "Gemcitabine from Actavis launched on patent expiry in EU markets". FierceBiotech. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Press release: Hospira launches two-gram vial of gemcitabine hydrochloride for injection". Hospira via News-Medical.Net. 16 November 2010. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015.

- hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ a b c d e f g "UK label". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. 5 June 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ a b "US formLabel" (PDF). FDA. June 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017. For label updates see FDA index page for NDA 020509 Archived 2017-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 3833614.

- PMID 28229078.

- S2CID 25477593.

- ^ a b "Gemcitabine". Macmillan Cancer Support. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-470-09254-5.

- PMID 28318633.

- PMID 21691573.

- ^ PMID 25162786.

- ^ PMID 16807468.

- ^ Fatima, M., Iqbal Ahmed, M. M., Batool, F., Riaz, A., Ali, M., Munch-Petersen, B., & Mutahir, Z. (2019). Recombinant deoxyribonucleoside kinase from Drosophila melanogaster can improve gemcitabine based combined gene/chemotherapy for targeting cancer cells. Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences, 19(4), 342-349. https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2019.4136

- PMID 17636467.

- ^ PMID 25681996.

- ^ PMID 24636495.

- ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

- ^ "Gemzar". European Medicines Agency. 24 September 2008. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- ^ Myers C (18 August 2009). "Patent for Lilly's cancer drug Gemzar invalidated". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- ^ Holman CM (Summer 2011). "Unpredictability in Patent Law and Its Effect on Pharmaceutical Innovation" (PDF). Missouri Law Review. 76 (3): 645–693. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-11. Retrieved 2017-05-06.

- ^ a b Ravicher DB (28 July 2010). "On the Generic Gemzar Patent Fight". Seeking Alpha. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012.

- ISBN 9781443879262. Archivedfrom the original on 2017-09-11.

- PMID 28322141.

- PMID 28142120.

- PMID 27531553.

- from the original on 3 July 2017.

- PMID 21681092.