Genetic code

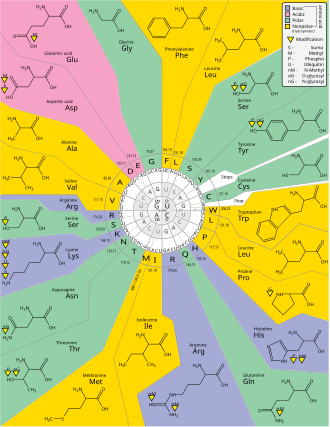

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living

The codons specify which amino acid will be added next during

History

Efforts to understand how proteins are encoded began after DNA's structure was discovered in 1953. The key discoverers, English biophysicist Francis Crick and American biologist James Watson, working together at the Cavendish Laboratory of the University of Cambridge, hypothesied that information flows from DNA and that there is a link between DNA and proteins.[2] Soviet-American physicist George Gamow was the first to give a workable scheme for protein synthesis from DNA.[3] He postulated that sets of three bases (triplets) must be employed to encode the 20 standard amino acids used by living cells to build proteins, which would allow a maximum of 43 = 64 amino acids.[4] He named this DNA–protein interaction (the original genetic code) as the "diamond code".[5]

In 1954, Gamow created an informal scientific organisation the RNA Tie Club, as suggested by Watson, for scientists of different persuasions who were interested in how proteins were synthesised from genes. However, the club could have only 20 permanent members to represent each of the 20 amino acids; and four additional honorary members to represent the four nucleotides of DNA.[6]

The first scientific contribution of the club, later recorded as "one of the most important unpublished articles in the history of science"[7] and "the most famous unpublished paper in the annals of molecular biology",[8] was made by Crick. Crick presented a type-written paper titled "On Degenerate Templates and the Adaptor Hypothesis: A Note for the RNA Tie Club"[9] to the members of the club in January 1955, which "totally changed the way we thought about protein synthesis", as Watson recalled.[10] The hypothesis states that the triplet code was not passed on to amino acids as Gamow thought, but carried by a different molecule, an adaptor, that interacts with amino acids.[8] The adaptor was later identified as tRNA.[11]

Codons

The Crick, Brenner, Barnett and Watts-Tobin experiment first demonstrated that codons consist of three DNA bases.

This was followed by experiments in

Subsequent work by

Extending this work, Nirenberg and

The three stop codons were named by discoverers Richard Epstein and Charles Steinberg. "Amber" was named after their friend Harris Bernstein, whose last name means "amber" in German.[19] The other two stop codons were named "ochre" and "opal" in order to keep the "color names" theme.

Expanded genetic codes (synthetic biology)

In a broad academic audience, the concept of the evolution of the genetic code from the original and ambiguous genetic code to a well-defined ("frozen") code with the repertoire of 20 (+2) canonical amino acids is widely accepted.[20] However, there are different opinions, concepts, approaches and ideas, which is the best way to change it experimentally. Even models are proposed that predict "entry points" for synthetic amino acid invasion of the genetic code.[21]

Since 2001, 40 non-natural amino acids have been added into proteins by creating a unique codon (recoding) and a corresponding transfer-RNA:aminoacyl – tRNA-synthetase pair to encode it with diverse physicochemical and biological properties in order to be used as a tool to exploring protein structure and function or to create novel or enhanced proteins.[22][23]

H. Murakami and M. Sisido extended some codons to have four and five bases. Steven A. Benner constructed a functional 65th (in vivo) codon.[24]

In 2015 N. Budisa, D. Söll and co-workers reported the full substitution of all 20,899 tryptophan residues (UGG codons) with unnatural thienopyrrole-alanine in the genetic code of the bacterium Escherichia coli.[25]

In 2016 the first stable semisynthetic organism was created. It was a (single cell) bacterium with two synthetic bases (called X and Y). The bases survived cell division.[26][27]

In 2017, researchers in South Korea reported that they had engineered a mouse with an extended genetic code that can produce proteins with unnatural amino acids.[28]

In May 2019, researchers reported the creation of a new "Syn61" strain of the

Features

Reading frame

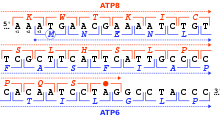

A reading frame is defined by the initial triplet of nucleotides from which translation starts. It sets the frame for a run of successive, non-overlapping codons, which is known as an "

In eukaryotes, ORFs in exons are often interrupted by introns.

Start and stop codons

Translation starts with a chain-initiation codon or

The three stop codons have names: UAG is amber, UGA is opal (sometimes also called umber), and UAA is ochre. Stop codons are also called "termination" or "nonsense" codons. They signal release of the nascent polypeptide from the ribosome because no cognate tRNA has anticodons complementary to these stop signals, allowing a release factor to bind to the ribosome instead.[34]

Effect of mutations

During the process of DNA replication, errors occasionally occur in the polymerization of the second strand. These errors, mutations, can affect an organism's phenotype, especially if they occur within the protein coding sequence of a gene. Error rates are typically 1 error in every 10–100 million bases—due to the "proofreading" ability of DNA polymerases.[36][37]

Mutations that disrupt the reading frame sequence by

Although most mutations that change protein sequences are harmful or neutral, some mutations have benefits.[44] These mutations may enable the mutant organism to withstand particular environmental stresses better than wild type organisms, or reproduce more quickly. In these cases a mutation will tend to become more common in a population through natural selection.[45] Viruses that use RNA as their genetic material have rapid mutation rates,[46] which can be an advantage, since these viruses thereby evolve rapidly, and thus evade the immune system defensive responses.[47] In large populations of asexually reproducing organisms, for example, E. coli, multiple beneficial mutations may co-occur. This phenomenon is called clonal interference and causes competition among the mutations.[48]

Degeneracy

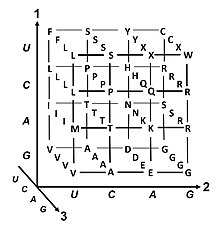

Degeneracy is the redundancy of the genetic code. This term was given by Bernfield and Nirenberg. The genetic code has redundancy but no ambiguity (see the

Codon usage bias

The frequency of codons, also known as codon usage bias, can vary from species to species with functional implications for the control of translation. The codon varies by organism; for example, most common proline codon in E. coli is CCG, whereas in humans this is the least used proline codon.[53]

Human genome codon frequency table[54]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alternative genetic codes

Non-standard amino acids

In some proteins, non-standard amino acids are substituted for standard stop codons, depending on associated signal sequences in the messenger RNA. For example, UGA can code for selenocysteine and UAG can code for pyrrolysine. Selenocysteine came to be seen as the 21st amino acid, and pyrrolysine as the 22nd.[55] Both selenocysteine and pyrrolysine may be present in the same organism.[55] Although the genetic code is normally fixed in an organism, the achaeal prokaryote Acetohalobium arabaticum can expand its genetic code from 20 to 21 amino acids (by including pyrrolysine) under different conditions of growth.[56]

Variations

There was originally a simple and widely accepted argument that the genetic code should be universal: namely, that any variation in the genetic code would be lethal to the organism (although Crick had stated that viruses were an exception). This is known as the "frozen accident" argument for the universality of the genetic code. However, in his seminal paper on the origins of the genetic code in 1968, Francis Crick still stated that the universality of the genetic code in all organisms was an unproven assumption, and was probably not true in some instances. He predicted that "The code is universal (the same in all organisms) or nearly so".[58] The first variation was discovered in 1979, by researchers studying human mitochondrial genes.[59] Many slight variants were discovered thereafter,[60] including various alternative mitochondrial codes.[61] These minor variants for example involve translation of the codon UGA as tryptophan in Mycoplasma species, and translation of CUG as a serine rather than leucine in yeasts of the "CTG clade" (such as Candida albicans).[62][63][64] Because viruses must use the same genetic code as their hosts, modifications to the standard genetic code could interfere with viral protein synthesis or functioning. However, viruses such as totiviruses have adapted to the host's genetic code modification.[65] In bacteria and archaea, GUG and UUG are common start codons. In rare cases, certain proteins may use alternative start codons.[60] Surprisingly, variations in the interpretation of the genetic code exist also in human nuclear-encoded genes: In 2016, researchers studying the translation of malate dehydrogenase found that in about 4% of the mRNAs encoding this enzyme the stop codon is naturally used to encode the amino acids tryptophan and arginine.[66] This type of recoding is induced by a high-readthrough stop codon context[67] and it is referred to as functional translational readthrough.[68]

Despite these differences, all known naturally occurring codes are very similar. The coding mechanism is the same for all organisms: three-base codons, tRNA, ribosomes, single direction reading and translating single codons into single amino acids.[69] The most extreme variations occur in certain ciliates where the meaning of stop codons depends on their position within mRNA. When close to the 3' end they act as terminators while in internal positions they either code for amino acids as in Condylostoma magnum[70] or trigger ribosomal frameshifting as in Euplotes.[71]

The origins and variation of the genetic code, including the mechanisms behind the evolvability of the genetic code, have been widely studied,[72][73] and some studies have been done experimentally evolving the genetic code of some organisms.[74][75][76][77]

Inference

Variant genetic codes used by an organism can be inferred by identifying highly conserved genes encoded in that genome, and comparing its codon usage to the amino acids in homologous proteins of other organisms. For example, the program FACIL infers a genetic code by searching which amino acids in homologous protein domains are most often aligned to every codon. The resulting amino acid (or stop codon) probabilities for each codon are displayed in a genetic code logo.[57]

As of January 2022, the most complete survey of genetic codes is done by Shulgina and Eddy, who screened 250,000 prokaryotic genomes using their Codetta tool. This tool uses a similar approach to FACIL with a larger

Origin

The genetic code is a key part of the

A hypothetical randomly evolved genetic code further motivates a biochemical or evolutionary model for its origin. If amino acids were randomly assigned to triplet codons, there would be 1.5 × 1084 possible genetic codes.[81]: 163 This number is found by calculating the number of ways that 21 items (20 amino acids plus one stop) can be placed in 64 bins, wherein each item is used at least once.[82] However, the distribution of codon assignments in the genetic code is nonrandom.[83] In particular, the genetic code clusters certain amino acid assignments.

Amino acids that share the same biosynthetic pathway tend to have the same first base in their codons. This could be an evolutionary relic of an early, simpler genetic code with fewer amino acids that later evolved to code a larger set of amino acids.[84] It could also reflect steric and chemical properties that had another effect on the codon during its evolution. Amino acids with similar physical properties also tend to have similar codons,[85][86] reducing the problems caused by point mutations and mistranslations.[83]

Given the non-random genetic triplet coding scheme, a tenable hypothesis for the origin of genetic code could address multiple aspects of the codon table, such as absence of codons for D-amino acids, secondary codon patterns for some amino acids, confinement of synonymous positions to third position, the small set of only 20 amino acids (instead of a number approaching 64), and the relation of stop codon patterns to amino acid coding patterns.[87]

Three main hypotheses address the origin of the genetic code. Many models belong to one of them or to a hybrid:[88]

- Random freeze: the genetic code was randomly created. For example, early

- Stereochemical affinity: the genetic code is a result of a high affinity between each amino acid and its codon or anti-codon; the latter option implies that pre-tRNA molecules matched their corresponding amino acids by this affinity. Later during evolution, this matching was gradually replaced with matching by aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases.[87][90][91]

- Optimality: the genetic code continued to evolve after its initial creation, so that the current code maximizes some fitness function, usually some kind of error minimization.[87][88][92]

Hypotheses have addressed a variety of scenarios:[93]

- Chemical principles govern specific RNA interaction with amino acids. Experiments with aptamers showed that some amino acids have a selective chemical affinity for their codons.[94] Experiments showed that of 8 amino acids tested, 6 show some RNA triplet-amino acid association.[81][91]

- Biosynthetic expansion. The genetic code grew from a simpler earlier code through a process of "biosynthetic expansion". Primordial life "discovered" new amino acids (for example, as by-products of metabolism) and later incorporated some of these into the machinery of genetic coding.[95] Although much circumstantial evidence has been found to suggest that fewer amino acid types were used in the past,[96] precise and detailed hypotheses about which amino acids entered the code in what order are controversial.[97][98] However, several studies have suggested that Gly, Ala, Asp, Val, Ser, Pro, Glu, Leu, Thr may belong to a group of early-addition amino acids, whereas Cys, Met, Tyr, Trp, His, Phe may belong to a group of later-addition amino acids.[99][100][101][102]

- Natural selection has led to codon assignments of the genetic code that minimize the effects of mutations.[103] A recent hypothesis[104] suggests that the triplet code was derived from codes that used longer than triplet codons (such as quadruplet codons). Longer than triplet decoding would increase codon redundancy and would be more error resistant. This feature could allow accurate decoding absent complex translational machinery such as the ribosome, such as before cells began making ribosomes.

- Information channels: map coloring problem.[109]

- Game theory: Models based on signaling games combine elements of game theory, natural selection and information channels. Such models have been used to suggest that the first polypeptides were likely short and had non-enzymatic function. Game theoretic models suggested that the organization of RNA strings into cells may have been necessary to prevent "deceptive" use of the genetic code, i.e. preventing the ancient equivalent of viruses from overwhelming the RNA world.[110]

- Stop codons: Codons for translational stops are also an interesting aspect to the problem of the origin of the genetic code. As an example for addressing stop codon evolution, it has been suggested that the stop codons are such that they are most likely to terminate translation early in the case of a

See also

- List of genetic engineering software

- Codon tables

References

- PMID 19131629.

- S2CID 4256010.

- PMID 27924115.

- OCLC 1020240407.

- S2CID 121907709.

- PMID 30846543.

- ^ "Francis Crick - Profiles in Science Search Results". profiles.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ S2CID 249112573.

- ^ Crick, Francis (1955). "On Degenerate Templates and the Adaptor Hypothesis: A Note for the RNA Tie Club". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- OCLC 47716375.

- PMID 26549858.

- S2CID 14249277.

- PMID 14479932.

- PMID 13946552.

- PMID 13998282.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959" (Press release). The Royal Swedish Academy of Science. 1959. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959 was awarded jointly to Severo Ochoa and Arthur Kornberg 'for their discovery of the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic acid'.

- PMID 5330357.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1968" (Press release). The Royal Swedish Academy of Science. 1968. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1968 was awarded jointly to Robert W. Holley, Har Gobind Khorana and Marshall W. Nirenberg 'for their interpretation of the genetic code and its function in protein synthesis'.

- PMID 15514035.

- ISBN 9783527312436.

- PMID 28671771.

- PMID 16260173.

- PMID 19318213.

- ISBN 978-0-387-22046-8.

- PMID 26136259. NIHMSID: NIHMS711205

- ^ "First stable semisynthetic organism created | KurzweilAI". www.kurzweilai.net. 3 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- PMID 28115716.

- PMID 28220771.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (15 May 2019). "Scientists Created Bacteria With a Synthetic Genome. Is This Artificial Life? - In a milestone for synthetic biology, colonies of E. coli thrive with DNA constructed from scratch by humans, not nature". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- S2CID 205571025.

- ^ Homo sapiens mitochondrion, complete genome. "Revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS): accession NC_012920", National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved on 27 December 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-976644-4.

- PMID 12867081.

- ^ Maloy S (29 November 2003). "How nonsense mutations got their names". Microbial Genetics Course. San Diego State University. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ References for the image are found in Wikimedia Commons page at: Commons:File:Notable mutations.svg#References.

- ISBN 978-0-7167-3520-5.

- PMID 15057282.

- PMID 17015226.

- PMID 88735.

- PMID 17015226.

- S2CID 22693748.

- S2CID 32918971.

- ISBN 978-0-07-111156-0.

- PMID 17409186.

- ^ Bridges KR (2002). "Malaria and the Red Cell". Harvard. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011.

- PMID 10570172.

- PMID 7041255.

- PMID 16489229.

- ISBN 978-3-540-53420-4.

- ^ Füllen G, Youvan DC (1994). "Genetic Algorithms and Recursive Ensemble Mutagenesis in Protein Engineering". Complexity International 1.

- ^ S2CID 51968530.

- ^ "Codon Usage Frequency Table(chart)-Genscript". www.genscript.com. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ "Codon usage table". www.kazusa.or.jp.

- ^ PMID 15788401.

- PMID 23185002.

- ^ PMID 21653513.

- ^ Francis Crick, 1968. "The Origin of the Genetic Code". J. Mol. Biol.

- ^ Barrell BG, Bankier AT, Drouin J (1979). "A different genetic code in human mitochondria". Nature. 282 (5735): 189–194. )

- ^ a b Elzanowski A, Ostell J (7 April 2008). "The Genetic Codes". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- S2CID 19264964.

- PMID 17121679.

- PMID 7784200.

- PMID 19465905.

- PMID 23638388.

- PMID 27881739.

- PMID 25247702.

- PMID 27490485.

- PMID 29030023.

- PMID 27501944.

- PMID 27870834.

- PMID 19117371.

- S2CID 15542587.

- S2CID 19385756.

- S2CID 19385756.

- PMID 20307192.

- PMID 24555827.

- PMID 34751130.

- PMID 36952281.

- PMID 9736730.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-674-05075-4.

- ^ "Mathematica function for # possible arrangements of items in bins? – Online Technical Discussion Groups—Wolfram Community". community.wolfram.com. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ S2CID 20130470.

- PMID 2650752.

- S2CID 20803686.

- PMID 6928661.

- ^ PMID 21779963.

- ^ PMID 10742043.

- S2CID 4144681.

- PMID 279919.

- ^ PMID 19795157.

- S2CID 257983174.

- PMID 10366854.

- PMID 9751648.

- S2CID 15542587.

- PMID 12270892.

- S2CID 23334860.

- PMID 11087835.

- PMID 19524038.

- S2CID 9039622.

- PMID 28180287.

- PMID 31504783.

- ^ S2CID 18823745.

- PMID 19479032.

- S2CID 12206140.

- ^ Sonneborn TM (1965). Bryson V, Vogel H (eds.). Evolving genes and proteins. New York: Academic Press. pp. 377–397.

- S2CID 12246664.

- S2CID 1260806.

- S2CID 1845965.

- PMID 23985735.

- PMID 17293451.

Further reading

- Griffiths AJ, Miller JH, Suzuki DT, Lewontin RC, Gilbert WM (1999). An Introduction to genetic analysis (7th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-3771-1.

- Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). Molecular biology of the cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3.

- Lodish HF, Berk A, Zipursky SL, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D, Darnell JE (2000). Molecular cell biology (4th ed.). San Francisco: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 9780716737063.

- Caskey CT, Leder P (April 2014). "The RNA code: nature's Rosetta Stone". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (16): 5758–9. PMID 24756939.

External links

- The Genetic Codes: Genetic Code Tables

- The Codon Usage Database — Codon frequency tables for many organisms

- History of deciphering the genetic code