Genetic history of Italy

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

The genetic history of Italy is greatly influenced by geography and history. The ancestors of

In their admixture ratios, Italians are similar to other Southern Europeans, and that is being of primarily

Overview

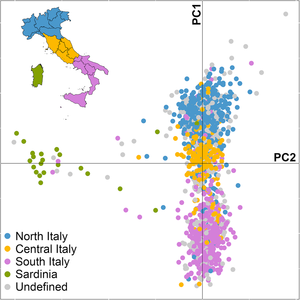

Multiple DNA studies confirmed that genetic variation in

The genetic gap between northern and southern Italians is filled by an intermediate Central Italian cluster, creating a continuous cline of variation that mirrors geography.[23] The only exceptions are some minority populations (mostly Slovene minorities from the region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia) who cluster with the Slavic-speaking Central Europeans in Slovenia,[24] as well as the Sardinians, who are clearly differentiated from the populations of both mainland Italy and Sicily.[12][4] A study on some linguistic and isolated communities residing in Italy revealed that their genetic diversity at short (0–200 km) and intermediate distances (700–800 km) was greater than that observed throughout the entire European continent.[5]

The genetic distance between Northern and Southern Italians, although large for a single European nationality, is similar to that between the Northern and the Southern Germans.[25] Northern and Southern Italians began to diverge as early as the Late Glacial, and appear to encapsulate at a smaller scale the cline of genetic diversity observable across Europe.[26]

Historical populations of Italy

Modern humans appeared during the Upper Paleolithic. Specimens of Aurignacian age were discovered in the cave of Fumane and date back about 34,000 years. During the Magdalenian period, the first humans from the Pyrenees populated Sardinia.[27]

During the

During the Late

At the dawn of the

From the 8th century BC, Greek colonists settled on the southern Italian coast and founded cities, forming what would be later called Magna Graecia. Around the same time, Phoenician colonists settled on the western side of Sicily. During the same period the Etruscan civilization developed on the coast of Southern Tuscany and Northern Latium. In the 4th century BC, Gauls settled in Northern Italy and in parts of Central Italy.[29] With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, different populations of Germanic origin invaded Italy, the most significant being the Lombards,[30] followed five centuries later by the Normans in Sicily.

Y-DNA genetic diversity

Many

A study from the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore found that while Greek colonization left little significant genetic contribution, data analysis sampling 12 sites in the Italian peninsula supported a male demic diffusion model and Neolithic admixture with Mesolithic inhabitants.[35] The results supported a distribution of genetic variation along a north–south axis and supported demic diffusion. South Italian samples clustered with southeast and south-central European samples, and northern groups with West Europe.[35][36]

A 2004 study by Semino et al. showed that Italians from the north-central regions had around 26.9% J2; the Apulians, Calabrians and

A 2018 genetic study, focusing on the

Y-DNA introduced by historical immigration

In two villages in

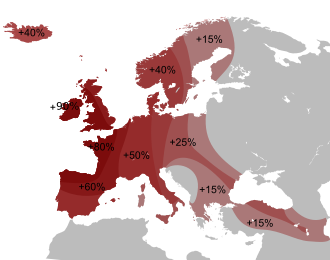

The Norman conquest of southern Italy caused the Norman Kingdom of Sicily to be created in 1130, with Palermo as capital, 70 years after the initial Norman invasion and 40 after the conquest of the last town, Noto in 1091, and would last until 1198. Nowadays it is in central and western Sicily, that Norman Y-DNA is common, with 15% to 20% of the lineages belonging to haplogroup I, this percentage drops to 8% in the eastern part of the island. The North African male contribution to Sicily was estimated between 0% and 7.5%.[43][18][44] Overall, the estimated Southern Balkan and Western European paternal contributions in Sicily are about 63% and 26% respectively.[44]

A 2015 genetic study of six small mountain villages in eastern

Genetic composition of Italian mtDNA

In Italy as elsewhere in Europe the majority of mtDNA lineages belong to the

African

A study in 2012 by Brisighelli et al. stated that an analysis of

A 2013 study by Alessio Boattini et al. found 0 of African L haplogroup in the whole Italy out of 865 samples. The percentages for Berber M1 and U6 haplogroups were 0.46% and 0.35%, respectively.[50]

A 2014 study by Stefania Sarno et al. found 0 of African L and M1 haplogroups in mainland Southern Italy out of 115 samples. Only two Berber U6 out of 115 samples were found, one from Lecce and one from Cosenza.[44]

A close genetic similarity between Ashkenazim and Italians has been noted in genetic studies, possibly due to the fact that Ashkenazi Jews have a significant European admixture (30–60%), much of it Southern European, a lot of which came from Italy when Jewish diaspora males of Middle Eastern origin migrated to Rome and found wives among local women who then converted to Judaism.[51][52][53][54][55][13][56] More specifically, Ashkenazi Jews could be modeled as being 50% Levantine and 50% European, with an estimated mean South European admixture of 37.5%. Most of it (30.5%) seems to derive from an Italian source.[57][58]

A 2010 study of Jewish genealogy found that with respect to non-Jewish European groups, the populations which are most closely related to Ashkenazi Jews are modern-day Italians followed by the French and Sardinians.[59][60]

Recent studies have shown that Italy played an important role in the recovery of "

A mtDNA study, published in 2018 in the journal

A 2020 analysis of maternal haplogroups from ancient and modern samples in the central Italian region of Umbria finds a substantial genetic similarity among modern Umbrians and the area's pre-Roman inhabitants, and evidence of substantial genetic continuity in the region from pre-Roman times to the present. Both modern and ancient Umbrians were found to have high rates of mtDNA haplogroups U4 and U5a, and an overrepresentation of J (at roughly 30%). The study also found that, "local genetic continuities are further attested to by six terminal branches (H1e1, J1c3, J2b1, U2e2a, U8b1b1 and K1a4a)" also shared by ancient and modern Umbrians.[6]

Autosomal

South/West European North/East European Caucasus

West Asian South Asian East Asian North African/Sub-Saharan African[63]

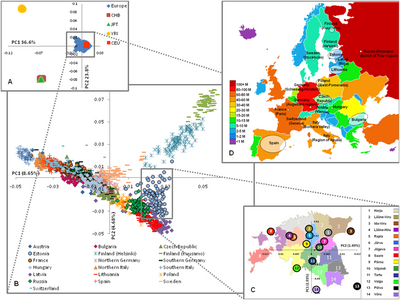

Wade et al. (2008) determined that Italy is one of the last two remaining genetic islands in Europe, the other being Finland. This is due in part to the presence of the Alpine mountain chain which, over the centuries, has prevented large migration flows. [64]

Recent genome-wide studies have been able to detect and quantify admixture like never before. Li et al. (2008), using more than 600,000 autosomal SNPs, identify seven global population clusters, including European, Middle Eastern and Central/South Asian. All the Italian samples belong to Central-Western group with minor influences dating to Neolithic period.[65]

López Herráez et al. (2009) typed the same samples at close to 1 million SNPs and analyzed them in a Western Eurasian context, identifying a number of subclusters. This time, all of the European samples show some minor admixture. Among the Italians, Tuscany still has the most, and Sardinia has a bit too, but so does Lombardy (Bergamo), which is even farther north.[66]

A 2011 study by Moorjani et al. found that many southern Europeans have inherited 1–3% Sub-Saharan ancestry, although the percentages were lower (0.2–2.1%) when reanalyzed with the 'STRUCTURE' statistical model. An average admixture date of around 55 generations/1100 years ago was also calculated, "consistent with North African gene flow at the end of the Roman Empire and subsequent Arab migrations"[67]

A 2012 study by Di Gaetano et al. used 1,014 Italians with wide geographical coverage. It showed that the current population of Sardinia can be clearly differentiated genetically from mainland Italy and Sicily, and that a certain degree of genetic differentiation is detectable within the current Italian peninsula population.

By using the ADMIXTURE software, the authors obtained at K = 4 the lowest cross-validation error. The HapMap CEU individuals showed an average Northern Europe (NE) ancestry of 83%. A similar pattern is observed in French, Northern Italian and Central Italian populations with a NE ancestry of 70%, 56% and 52% respectively. According to the PCA plot, also in the ADMIXTURE analysis there are relatively small differences in ancestry between Northern Italians and Central Italians while Southern Italians showed a lower average admixture NE proportion (44%) than Northern and Central Italy, and a higher Caucasian ancestry of 28%. The Sardinian samples display a pattern of crimson common to the others European populations but at a higher frequency (70%). The average admixture proportions for Northern European ancestry within current Sardinian population is 14.3% with some individuals exhibiting very low Northern European ancestry (less than 5% in 36 individuals on 268 accounting the 13% of the sample).[12]

A 2013 study by Peristera Paschou et al. confirms that the Mediterranean Sea has acted as a strong barrier to gene flow through geographic isolation following initial settlements. Samples from (Northern) Italy, Tuscany, Sicily and Sardinia are closest to other Southern Europeans from Iberia, the Balkans and Greece, who are in turn closest to the Neolithic migrants that spread farming throughout Europe, represented here by the Cappadocian sample from Anatolia. But there hasn't been any significant admixture from the Middle East or North Africa into Italy and the rest of Southern Europe since then.[14]

Ancient DNA analysis reveals that Ötzi the Iceman clusters with modern Southern Europeans and closest to Italians (the orange "Europe S" dots in the plots below), especially those from the island of Sardinia. Other Italians pull away toward Southeastern and Central Europe consistent with geography and some post-Neolithic gene flow from those areas (e.g. Italics, Greeks, Etruscans, Celts), but despite that and centuries of history, they're still very similar to their prehistoric ancestor.[68]

A 2013 study by Botigué et al. 2013 applied an unsupervised clustering algorithm, ADMIXTURE, to estimate allele-based sharing between Africans and Europeans. Regarding Italians, the North African ancestry does not exceed 2% of their genomes. On average, 1% of Jewish ancestry is found in Tuscan HapMap population and Italian Swiss, as well as Greeks and Cypriots. Contrary to past observations, Sub-Saharan ancestry is detected at <1% in Europe, with the exception of the Canary Islands.[44]

Haak et al. (2015) conducted a genome wide study of 94 ancient skeletons from Europe and Russia. The study argues that Bronze Age steppe pastoralists from the

A 2016 study Sazzini et al., confirms the results of previous studies by Di Gaetano et al. (2012) and Fiorito et al. (2015) but has much better geographical coverage of samples, with 737 individuals from 20 locations in 15 different regions being tested. The study also for the first time includes a formal admixture test that models the ancestry of Italians by inferring admixture events using all of the Western Eurasian samples. The results are very interesting in light of the ancient DNA evidence that has come out in the last couple years:

In addition to the pattern described in the main text, the SARD sample seemed to have played a major role as source of admixture for most of the examined populations, especially Italian ones, rather than as recipient of migratory processes. In fact, the most significant f3 scores for trios including SARD indicated peninsular Italians as plausible results of admixture between SARD and populations from Iran, Caucasus and Russia. This scenario could be interpreted as further evidence that Sardinians retain high proportions of a putative ancestral genomic background that was considerably widespread across Europe at least until the Neolithic and that has been subsequently erased or masked in most of present-day European populations.[23]

Sarno et al. (2017) concentrate on the genetic impact brought by the historical migrations around the Mediterranean on

Raveane et al. (2019) discovered in a genome-wide study on modern-day Italians a contribution of

Antonio et al. (2019) studied historical populations from various time periods in

A 2022 genome-wide study of more than 700 individuals from the South Mediterranean area (102 from Southern Italy), combined with ancient DNA from neighbouring areas, found high affinities of South-Eastern Italians with modern Eastern Peloponnesians, and a closer affinity of ancient Greek genomes with those from specific regions of South Italy than modern Greek genomes.[69]

See also

- Demographics of Italy

- European ethnic groups

- Genetic history of Europe

References

- PMID 26553317.

- ^ PMID 31699931.

Interestingly, although Iron Age individuals were sampled from both Etruscan (n=3) and Latin (n=6) contexts, we did not detect any significant differences between the two groups with f4 statistics in the form of f4(RMPR_Etruscan, RMPR_Latin; test population, Onge), suggesting shared origins or extensive genetic exchange between them. ... In the Medieval and early modern periods (n = 28 individuals), we observe an ancestry shift toward central and northern Europe in PCA (Fig. 3E), as well as a further increase in the European cluster (C7) and loss of the Near Eastern and eastern Mediterranean clusters (C4 and C5) in ChromoPainter (Fig. 4C). The Medieval population is roughly centered on modern-day central Italians (Fig. 3F). It can be modeled as a two-way combination of Rome's Late Antique population and a European donor population, with potential sources including many ancient and modern populations in central and northern Europe: Lombards from Hungary, Saxons from England, and Vikings from Sweden, among others (table S26).

- PMID 23667324.

- ^ PMID 31517044.

- ^ PMID 24607994.

- ^ PMID 32612271.

- ^ PMID 30224645.

- ^ PMID 32094358.

- ^ PMID 32094539.

- ISBN 978-0-691-08750-4.

- ^ PMID 25731166.

- ^ PMID 22984441.

- ^ PMID 18208327.

- ^ PMID 24927591.

- ^ PMID 26554880.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, p. 2.

- ^ PMID 18685561.

The genetic contribution of Greek chromosomes to the Sicilian gene pool is estimated to be about 37% whereas the contribution of North African populations is estimated to be around 6%.

- ^ PMID 28512355.

- ^ Antonio et al. 2019, p. 3.

- S2CID 207965960. Archived from the originalon 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2021-01-25."Trade routes sent people and goods to the new capital, and epidemics and invasions reduced Rome's population to about 100,000 people. Invading barbarians brought in more European ancestry. Rome gradually lost its strong genetic link to the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. By medieval times, city residents again genetically resembled European populations."

- ^ ..."La separazione della Sardegna dal resto del continente, anzi da tutte le altre popolazioni europee, che probabilmente rivela un'origine più antica della sua popolazione, indipendente da quella delle popolazioni italiche e con ascendenze nel Mediterraneo Medio-Orientale." Alberto Piazza, I profili genetici degli italiani, Accademia delle Scienze di Torino

- ^ PMID 23251386.

- ^ PMID 27582244. Zendo: 165505.

- PMID 23249956.

- ^ PMID 19424496.

- PMID 32438927.

- doi:10.4312/dp.33.3. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2009-03-06.

- ^ "Culture del bronzo recente in Italia settentrionale e loro rapporti con la "cultura dei campi di urne"". Gruppo Archeologico Monteclarense. Archived from the original on 10 May 2006.

- ISBN 978-1-317-87017-3.

- ^ "Lombard people". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ S2CID 43501209.

- PMID 12927125. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2017-01-20.

- PMID 12772214.

- PMID 23908240.

- ^ PMID 17275346.

- ISBN 978-0-691-08750-4.>: 295

- PMID 15069642.

- ISBN 978-0-631-22038-1.

- ISBN 978-1-61451-520-3.

- ISBN 9781444337341.

- ISBN 9781780238623.

- ^ S2CID 30111156.

- PMID 19156170.

- ^ PMID 24788788..

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license - PMID 23251386. In Table S4, #BEL50 is estimated to be Q-M378 by haplotype, though it is shown as just P* (xR1).

- ^ PMID 15632086.

- PMID 11032788.

- PMID 15382008.

- PMID 17357081.

4/138=2.9% in Latium; 3/114=2.6% in Volterra; 2/92=2.2% in Basilicata and 3/154=2.0% in Sicily

- PMID 23734255.

- ^ Balter M (3 June 2010). "Tracing the Roots of Jewishness". Science Magazine. American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- PMID 20925954.

- ^ Balter M (8 October 2013). "Did Modern Jews Originate in Italy?". ScienceNOW.

- ^ Yandell K (2013). "Genetic Roots of the Ashkenazi Jews". The Scientist.

- S2CID 8127224.

- PMID 24104924.

- ^ Banda Y, Kvale M, Hoffmann T, Hesselson S, Tang H, Ranatunga D, et al. (2013). "Admixture Estimation in a Founder Population". Am Soc Hum Genet. Archived from the original on 2019-08-11. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- PMID 20798349.

- PMID 20560205.

- ^ "Genes Set Jews Apart, Study Finds". American Scientist. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- "Study finds genetic links among Jewish people". EurekAlert! (Press release). 3 June 2010.

- PMID 19500771. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2018-07-22. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- S2CID 52161000.

- PMID 25148043.

- ^ Wade N (13 August 2008). "Genetic Map of Europe". New York Times. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- S2CID 53541133. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2009-03-27.

- PMID 19924308.

- PMID 21533020.

- PMID 22426219.

- )

Further reading

- Saupe, Tina et al. "Ancient genomes reveal structural shifts after the arrival of Steppe-related ancestry in the Italian Peninsula". In: Current Biology Volume 31, Issue 12, 21 June 2021, Pages 2576–2591.e12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.04.022