Geography and cartography in the medieval Islamic world

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (February 2019) |

Medieval Islamic geography and cartography refer to the study of

History

8th and 9th century

Islamic geography began in the 8th century, influenced by Hellenistic geography,

Islamic geography was patronized by the

Islamic cartographers inherited Ptolemy's

Having received Greek writings directly and without Latin intermediation, Arabian and Persian geographers made no use of

In the 9th century, the

Khordadbeh–Jayhani tradition

The works of Ibn Khordadbeh (c. 870) and Jayhani (c. 910s) were at the basis of a new Perso-Arab tradition in Persia and Central Asia.[10] The exact relationship between the books of Khordadbeh and Jayhani is unknown, because the two books had the same title, have often been mixed up, and Jayhani's book has been lost, so that it can only be approximately reconstructed from the works of other authors (mostly from the eastern parts of the Islamic world[11]) who seem to have reused some of its contents.[10][12] According to Vasily Bartold, Jayhani based his book primarily on the data he had collected himself, but also reused Khordadbeh's work to a considerable extent.[10] Unlike the Balkhi school, geographers of the Khordadbeh–Jayhani tradition sought to describe the whole world as they knew it, including the lands, societies and cultures of non-Muslims.[13] As vizier of the Samanid Empire, Jayhani's diplomatic correspondence allowed him to collect much valuable information from people in faraway lands.[14] Nevertheless, Al-Masudi criticised Jayhani for overemphasising geological features of landscapes, stars and geometry, taxation systems, trade roads and stations allegedly few people used, while ignoring major population centres, provinces and military roads and forces.[15]

Balkhi school

The Balkhī school of terrestrial mapping, originated by

Regional cartography

Islamic regional cartography is usually categorized into three groups: that produced by the "

The maps by the Balkhī schools were defined by political, not longitudinal boundaries and covered only the Muslim world. In these maps the distances between various "stops" (cities or rivers) were equalized. The only shapes used in designs were verticals, horizontals, 90-degree angles, and arcs of circles; unnecessary geographical details were eliminated. This approach is similar to that used in

Al-Idrīsī defined his maps differently. He considered the extent of the known world to be 160° and had to symbolize 50 dogs in longitude and divided the region into ten parts, each 16° wide. In terms of latitude, he portioned the known world into seven 'climes', determined by the length of the longest day. In his maps, many dominant geographical features can be found.[4]

Book on the appearance of the Earth

Al-Khwārizmī,

Al-Biruni

In his Codex Masudicus (1037), Al-Biruni theorized the existence of a landmass along the vast ocean between Asia and Europe, or what is today known as the Americas. He argued for its existence on the basis of his accurate estimations of the Earth's circumference and Afro-Eurasia's size, which he found spanned only two-fifths of the Earth's circumference, reasoning that the geological processes that gave rise to Eurasia must surely have given rise to lands in the vast ocean between Asia and Europe. He also theorized that at least some of the unknown landmass would lie within the known latitudes which humans could inhabit, and therefore would be inhabited.[22]

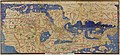

Tabula Rogeriana

The Arab geographer

On the work of al-Idrisi, S. P. Scott commented:[23]

The compilation of Edrisi marks an era in the history of science. Not only is its historical information most interesting and valuable, but its descriptions of many parts of the earth are still authoritative. For three centuries geographers copied his maps without alteration. The relative position of the lakes which form the Nile, as delineated in his work, does not differ greatly from that established by Baker and Stanley more than seven hundred years afterwards, and their number is the same. The mechanical genius of the author was not inferior to his erudition. The celestial and terrestrial planisphere of silver which he constructed for his royal patron was nearly six feet in diameter, and weighed four hundred and fifty pounds; upon the one side the zodiac and the constellations, upon the other—divided for convenience into segments—the bodies of land and water, with the respective situations of the various countries, were engraved.

— S. P. Scott, History of the Moorish Empire in Europe

Al-Idrisi's atlas, originally called the Nuzhat in Arabic, served as a major tool for Italian, Dutch and French mapmakers from the 16th century to the 18th century.[25]

Piri Reis map

The Piri Reis map is a world map compiled in 1513 by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis. Approximately one third of the map survives; it shows the western coasts of Europe and North Africa and the coast of Brazil with reasonable accuracy. Various Atlantic islands, including the Azores and Canary Islands, are depicted, as is the mythical island of Antillia and possibly Japan.

Others

Suhrāb, a late 10th-century Muslim geographer, accompanied a book of geographical

In the 11th century, the Karakhanid Turkic scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari was the first to draw a unique Islamic world map,[26] where he illuminated the cities and places of the Turkic peoples of Central and Inner Asia. He showed the lake Issyk-Kul (in nowadays Kyrgyzstan) as the centre of the world.

Ibn Battuta (1304–1368?) wrote "Rihlah" (Travels) based on three decades of journeys, covering more than 120,000 km through northern Africa, southern Europe, and much of Asia.

Instruments

Muslim scholars invented and refined a number of scientific instruments in mathematical geography and cartography. These included the astrolabe, quadrant, gnomon, celestial sphere, sundial, and compass.[1]

Astrolabe

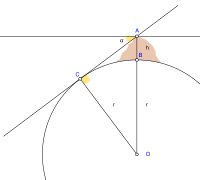

The mathematical background was established by Muslim astronomer

Compass

The earliest reference to a

Late in the 13th century, the

In 1300, an Arabic treatise written by the

In the 15th century, the description given by

Premodern Arabic sources refer to the compass using the term ṭāsa (lit. "bowl") for the floating compass, or ālat al-qiblah ("qibla instrument") for a device used for orienting towards Mecca.[36]

Friedrich Hirth suggested that Arab and Persian traders, who learned about the polarity of the magnetic needle from the Chinese, applied the compass for navigation before the Chinese did.[44] However, Needham described this theory as "erroneous" and "it originates because of a mistranslation" of the term chia-ling found in Zhu Yu's book Pingchow Table Talks.[45]

Notable geographers

Khordadbeh–Jayhani tradition geographers

- Ibn Khordadbeh (820–912): Kitāb al-Masālik wa-l-Mamālik ("Book of Roads and Kingdoms")[10]

- Abu Abdallah Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Jayhani (died 925): Kitāb al-Masālik wal-Mamālik ("Book of Roads and Kingdoms", lost)[10]

- Ahmad ibn Rustah (10th century)[14]

- Al-Masudi (896–956):[10][46] The Meadows of Gold[46]

- Al-Bakri (c. 1040–1094)[14]

- Gardizi (died 1061)[14]

- Muhammad Aufi[14]

Balkhi school geographers

- Abu Zayd al-Balkhi (850–934): Suwar al-aqālīm ("Images of the Climes")[11] or al-Amthila wa-suwar al-ard ("Similitudes and Images of the Earth"), written in 920 or after[11]

- Istakhri (died mid-10th century): al-Masālik wal-Mamālik ("Roads and Kingdoms").[47][48]

- Ibn Hawqal (died after 978):[13][49] Kitāb Sūrat al-ard[13] ("Book of the Face of the Earth")

- Al-Maqdisi (c. 945/946–991):[13][49] Aḥsan al-taqāsīm fi maʾarfat al-aqalīm[13] ("The Finest Divisions Concerning Knowledge of the Climes")[13]

- (probably) Hafiz-i Abru (died 1430)[13]

- Istakhri (died mid-10th century): al-Masālik wal-Mamālik ("Roads and Kingdoms").[47][48]

Others

- Al-Kindi (Alkindus, 801–873)

- Ya'qubi (died 897)

- Al-Dinawari(820–898)

- Khashkhash Ibn Saeed Ibn Aswad (fl. 889)

- Hamdani(893–945)

- Ibn al-Faqih (10th century)

- Ahmad ibn Fadlan (10th century)

- Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen, 965–1039)

- Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī(973–1048)

- Ibn Sina (Avicenna, 980–1037)

- Muhammad al-Idrisi (Dreses, 1100–1165)

- Ibn Rushd (Averroes, 1126–1198)

- Ibn Jubayr (1145–1217)

- Yaqut al-Hamawi (1179–1229)

- Hamdollah Mostowfi(1281–1349)

- Ibn al-Wardi (1291–1348)

- Ibn Battuta (1304–1370s)

- Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406)

- Ahmad Bin Majid(born 1432)

- Mahmud al-Kashgari (1005–1102)

- Piri Reis (1465–1554)

- Amin Razi(16th century)

Gallery

-

Al-Masudi's world map (10th century)

-

Schematic map of Sicily in the Arabic Book of Curiosities

-

10th century map of the World by Ibn Hawqal.

-

The Persian Gulf in a regional map of the Atlas of Islam

-

Map from Mahmud al-Kashgari's Diwan (11th century)

-

Ibn al-Wardi's atlas of the world (14th century), a manuscript copied in the 17th century

See also

References

Citations

- ^ ISBN 978-94-007-3934-5.

A prominent feature of the achievement of Muslim scholars in mathematical geography and cartography was the invention of scientific instruments of measurement. Among these were the astrolab (astrolabe), the ruba (quadrant), the gnomon, the celestial sphere, the sundial, and the compass.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-12410-2.

- ISBN 0-226-31635-1

- ^ a b c d e f Edson and Savage-Smith (2004)[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Edson & Savage-Smith 2004, pp. 61–63.

- ISBN 978-0-444-50328-2.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Arrayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- ^ King, David A. (1996). "Astronomy and Islamic society: Qibla, gnomics and timekeeping". In Rashed, Roshdi (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Vol. 1. London, UK and New York, USA: Routledge. pp. 128–184.

- ^ Rankin, Bill (2006). "Projection Reference". Radical Cartography.

- ^ a b c d e f Bosworth & Asimov 2003, p. 217–218.

- ^ a b c d Bosworth & Asimov 2003, p. 218.

- ^ Minorsky 1937, p. xvi–xvii.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bosworth & Asimov 2003, p. 219.

- ^ a b c d e Minorsky 1937, p. xvii.

- ^ Minorsky 1937, p. xviii.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Cartography", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- S2CID 145173935. Archived from the originalon 2008-05-12. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ^ Pingree 2010b.

- S2CID 119230163.

- ^ Douglas (1973, p.211)

- ISBN 9780674072824.

- ^ Starr, S. Frederick (12 December 2013). "So, Who Did Discover America? | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ a b Scott, S. P. (1904). History of the Moorish Empire in Europe. Harvard University Press. pp. 461–2.

- ^ "Slide #219: World Maps of al-Idrisi". Henry Davis Consulting.

- ISBN 9781135459321.

- ^ Hermann A. Die älteste türkische Weltkarte (1076 η. Ch.) // Imago Mundi: Jahrbuch der Alten Kartographie. — Berlin, 1935. — Bd.l. — S. 21—28.

- S2CID 161732080

- ISSN 1475-4878.

- ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9

- Richard Nelson Frye: Golden Age of Persia. p. 163

- ^ Dr. Emily Winterburn (National Maritime Museum), Using an Astrolabe, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation, 2005.

- ISBN 978-0-521-80040-2.

- ^ doi:10.5617/jais.4547. http://www.uib.no/jais/v001ht/01-081-132schmidl1.htm#_ftn4 Archived 2014-09-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ JSTOR 3102323

- ^ Jawāmeʿ al-ḥekāyāt wa-lawāmeʿ al-rewāyāt by Muhammad al-ʿAwfī

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-981257-8.

- ^ Needham p. 12-13 "...that the floating fish-shaped iron leaf spread outside China as a technique, we know from the description of Muhammad al' Awfi just two hundred years later"

- ^ Kitāb Kanz al-tujjār fī maʿrifat al-aḥjār

- ^ a b "Early Arabic Sources on the Magnetic Compass" (PDF). Lancaster.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- S2CID 33884974.

- ISBN 9780387310220. (PDF version)

- ^ (King 1983, pp. 547–8)

- S2CID 120284234.

- ^ Hirth, Friedrich (1908). Ancient history of China to the end of the Chóu dynasty. New York, The Columbia university press. p. 134.

- ISBN 978-0-521-05802-5.

- ^ a b Minorsky 1937, p. xix.

- ^ Bosworth & Asimov 2003, p. 218–219.

- ^ Minorsky 1937, p. xviii–xix, 5.

- ^ a b Minorsky 1937, p. xviii–xix.

Sources

- Alavi, S. M. Ziauddin (1965), Arab geography in the ninth and tenth centuries, Aligarh: Aligarh University Press

- Bosworth, C. E.; Asimov, M. S., eds. (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Volume IV. The age of achievement: A. D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 745. ISBN 9788120815964.

- Douglas, A. Vibert (1973), "Al-Biruni, Persian Scholar, 973–1048", Bibcode:1973JRASC..67..209D

- Edson, Evelyn; ISBN 978-1-85124-184-2.

- King, David A. (1983), "The Astronomy of the Mamluks", S2CID 144315162

- King, David A. (2002), "A Vetustissimus Arabic Text on the Quadrans Vetus", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 33: 237–255, S2CID 125329755

- King, David A. (December 2003), "14th-Century England or 9th-Century Baghdad? New Insights on the Elusive Astronomical Instrument Called Navicula de Venetiis",

- King, David A. (2005), In Synchrony with the Heavens, Studies in Astronomical Timekeeping and Instrumentation in Medieval Islamic Civilization: Instruments of Mass Calculation, ISBN 90-04-14188-X

- McGrail, Sean (2004), Boats of the World, ISBN 0-19-927186-0

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1937). Hudud al-'Alam, The Regions of the World A Persian Geography, 372 A.H. - 982 A.D. translated and explained by V. Minorsky (PDF). London: Luzac & Co. p. 546.

- Mott, Lawrence V. (May 1991), The Development of the Rudder, A.D. 100-1337: A Technological Tale, Thesis, Texas A&M University

- Pingree, David (2010b). "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN iv. Geography". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis (1996), ISBN 0-415-12410-7

- Sezgin, Fuat (2000), Geschichte Des Arabischen Schrifttums X–XII: Mathematische Geographie und Kartographie im Islam und ihr Fortleben im Abendland, Historische Darstellung, Teil 1–3 (in German), )