George V

| George V | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Formal portrait, 1923 | |||||

| |||||

| Reign | 6 May 1910 – 20 January 1936 | ||||

| Coronation | 22 June 1911 | ||||

| Imperial Durbar | 12 December 1911 | ||||

| Predecessor | Edward VII | ||||

| Successor | Edward VIII | ||||

| Born | Prince George of Wales 3 June 1865 Marlborough House, Westminster, Middlesex, England | ||||

| Died | 20 January 1936 (aged 70) Sandringham House, Norfolk, England | ||||

| Burial | 28 January 1936 Royal Vault, St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle 27 February 1939North Nave Aisle, St George's Chapel | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue Detail | |||||

| |||||

| House |

| ||||

| Father | Protestant | ||||

| Signature | |||||

| Military career | |||||

| Service | Royal Navy | ||||

| Years of active service | 1877–1892 | ||||

| Rank | Full list | ||||

| Commands held |

| ||||

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was

George was born during the reign of his paternal grandmother,

George's reign saw the rise of

George suffered from smoking-related health problems during his later reign. On his death in January 1936, he was succeeded by his eldest son, Edward VIII. Edward abdicated in December of that year and was succeeded by his younger brother Albert, who took the regnal name George VI.

Early life and education

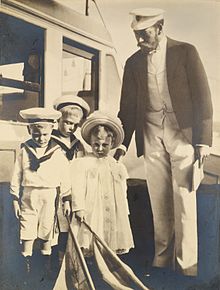

George was born on 3 June 1865, in

As a younger son of the Prince of Wales, there was little expectation that George would become king. He was third in line to the throne, after his father and elder brother,

For three years from 1879, the princes served on

Marriage

As a young man destined to serve in the navy, Prince George served for many years under the command of his uncle

In November 1891, George's brother, Albert Victor, became engaged to his second cousin once removed

On 14 January 1892, six weeks after the formal engagement, Albert Victor died of pneumonia during an influenza pandemic, leaving George second in line to the throne and likely to succeed after his father. George had only just recovered from a serious illness himself, having been confined to bed for six weeks with typhoid fever, the disease that was thought to have killed his grandfather Prince Albert.[14] Queen Victoria still regarded Princess May as a suitable match for her grandson, and George and May grew close during their shared period of mourning.[15]

A year after Albert Victor's death, George proposed to May and was accepted. They married on 6 July 1893 at the Chapel Royal in St James's Palace, London. Throughout their lives, they remained devoted to each other. George was, on his own admission, unable to express his feelings easily in speech, but they often exchanged loving letters and notes of endearment.[16]

Duke of York

The death of his elder brother effectively ended George's naval career, as he was now second in line to the throne, after his father.

The Duke and Duchess of York had five sons and a daughter. Randolph Churchill claimed that George was a strict father, to the extent that his children were terrified of him, and that George had remarked to the Earl of Derby: "My father was frightened of his mother, I was frightened of my father, and I am damned well going to see to it that my children are frightened of me." In reality, there is no direct source for the quotation and it is likely that George's parenting style was little different from that adopted by most people at the time.[20] Whether this was the case or not, his children did seem to resent his strict nature, his son Prince Henry going as far as to describe him as a "terrible father" in later years.[21]

They lived mainly at

In October 1894, George's maternal uncle-by-marriage,

Prince of Wales

As Duke of York, George carried out a wide variety of public duties. On the

In 1901, the Duke and Duchess toured the

In Australia, George opened the first session of the

On 9 November 1901, George was created

From November 1905 to March 1906, George and May toured

Reign

On 6 May 1910, Edward VII died, and George became king. He wrote in his diary:

I have lost my best friend and the best of fathers ... I never had a [cross] word with him in my life. I am heart-broken and overwhelmed with grief but God will help me in my responsibilities and darling May will be my comfort as she has always been. May God give me strength and guidance in the heavy task which has fallen on me.[43]

George had never liked his wife's habit of signing official documents and letters as "Victoria Mary" and insisted she drop one of those names. They both thought she should not be called Queen Victoria, and so she became Queen Mary.[44] Later that year, a radical propagandist, Edward Mylius, published a lie that George had secretly married in Malta as a young man, and that consequently his marriage to Queen Mary was bigamous. The lie had first surfaced in print in 1893, but George had shrugged it off as a joke. In an effort to kill off rumours, Mylius was arrested, tried and found guilty of criminal libel, and was sentenced to a year in prison.[45]

George objected to the

As he and Mary travelled throughout the subcontinent, George took the opportunity to indulge in

National politics

George inherited the throne at a politically turbulent time.

Asquith attempted to curtail the power of the Lords through constitutional reforms, which were again blocked by the Upper House. A constitutional conference on the reforms broke down in November 1910 after 21 meetings. Asquith and

The 1910 general elections had left the Liberals as a minority government dependent upon the support of the

First World War

On 4 August 1914, George wrote in his diary, "I held a council at 10:45 to declare war with Germany. It is a terrible catastrophe but it is not our fault. ... Please to God it may soon be over."

On 17 July 1917, George appeased British nationalist feelings by issuing a royal proclamation that changed the name of the British

In letters patent gazetted on 11 December 1917, the King restricted the style of "Royal Highness" and the titular dignity of "Prince (or Princess) of Great Britain and Ireland" to the children of the Sovereign, the children of the sons of the Sovereign and the eldest living son of the eldest son of a Prince of Wales.[71] The letters patent also stated that "the titles of Royal Highness, Highness or Serene Highness, and the titular dignity of Prince and Princess shall cease except those titles already granted and remaining unrevoked". George's relatives who fought on the German side, such as Ernest Augustus, Crown Prince of Hanover, and Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, had their British peerages suspended by a 1919 Order in Council under the provisions of the Titles Deprivation Act 1917. Under pressure from his mother, George also removed the Garter flags of his German relations from St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[72]

When Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, George's first cousin, was overthrown in the

Two months after the end of the war, the King's youngest son, John, died aged 13 after a lifetime of ill health. George was informed of his death by Queen Mary, who wrote, "[John] had been a great anxiety to us for many years ... The first break in the family circle is hard to bear but people have been so kind & sympathetic & this has helped us much."[79]

In May 1922, George toured Belgium and northern France, visiting the First World War cemeteries and memorials being constructed by the

Post-war reign

Before the

Political turmoil in Ireland continued as the Nationalists

George and his advisers were concerned about the rise of socialism and the growing labour movement, which they mistakenly associated with republicanism. The socialists no longer believed in their anti-monarchical slogans and were ready to come to terms with the monarchy if it took the first step. George adopted a more democratic, inclusive stance that crossed class lines and brought the monarchy closer to the public and the working class—a dramatic change for the King, who was most comfortable with naval officers and landed gentry. He cultivated friendly relations with moderate Labour Party politicians and trade union officials. His abandonment of social aloofness conditioned the royal family's behaviour and enhanced its popularity during the economic crises of the 1920s and for over two generations thereafter.[90][91]

The years between 1922 and 1929 saw frequent changes in government. In 1924, George appointed the first Labour Prime Minister,

In 1926, George hosted an

In the wake of a world financial crisis, George encouraged the formation of a National Government in 1931 led by MacDonald and Baldwin,[96][b] and volunteered to reduce the civil list to help balance the budget.[96] He was concerned by the rise to power in Germany of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party.[99] In 1934, George bluntly told the German ambassador Leopold von Hoesch that Germany was now the peril of the world, and that there was bound to be a war within ten years if Germany went on at the present rate; he warned the British ambassador in Berlin, Eric Phipps, to be suspicious of the Nazis.[100]

In 1932, George agreed to deliver a

George's relationship with his eldest son and heir, Edward, deteriorated in these later years. George was disappointed in Edward's failure to settle down in life and appalled by his many affairs with married women.[17] In contrast, he was fond of his second son, Prince Albert (later George VI), and doted on his eldest granddaughter, Princess Elizabeth; he nicknamed her "Lilibet", and she affectionately called him "Grandpa England".[103] In 1935, George said of his son Edward: "After I am dead, the boy will ruin himself within 12 months", and of Albert and Elizabeth: "I pray to God my eldest son will never marry and have children, and that nothing will come between Bertie and Lilibet and the throne".[104][105]

Declining health and death

The First World War took a toll on George's health: he was seriously injured on 28 October 1915 when thrown by his horse at a troop review in France,

George never fully recovered. In his final year, he was occasionally administered oxygen.[115] The death of his favourite sister, Victoria, in December 1935 depressed him deeply. On the evening of 15 January 1936, George took to his bedroom at Sandringham House complaining of a cold; he remained in the room until his death.[116] He became gradually weaker, drifting in and out of consciousness. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin later said:

... each time he became conscious it was some kind inquiry or kind observation of someone, some words of gratitude for kindness shown. But he did say to his secretary when he sent for him: "How is the Empire?" An unusual phrase in that form, and the secretary said: "All is well, sir, with the Empire", and the King gave him a smile and relapsed once more into unconsciousness.[117]

By 20 January, George was close to death. His physicians, led by

At about 11 o'clock it was evident that the last stage might endure for many hours, unknown to the Patient but little comporting with that dignity and serenity which he so richly merited and which demanded a brief final scene. Hours of waiting just for the mechanical end when all that is really life has departed only exhausts the onlookers & keeps them so strained that they cannot avail themselves of the solace of thought, communion or prayer. I therefore decided to determine the end and injected (myself) morphia gr.3/4 [grains] and shortly afterwards cocaine gr.1 [grains] into the distended jugular vein ... In about 1/4 an hour – breathing quieter – appearance more placid – physical struggle gone.[123]

Dawson wrote that he acted to preserve the King's dignity, to prevent further strain on the family, and so that George's death at 11:55 pm could be announced in the morning edition of

The German composer Paul Hindemith went to a BBC studio on the morning after the King's death and in six hours wrote Trauermusik ("Mourning Music"), for viola and orchestra. It was performed that same evening in a live broadcast by the BBC, with Adrian Boult conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the composer as soloist.[126] At the procession to George's lying in state in Westminster Hall, the cross surmounting the Imperial State Crown atop George's coffin fell off and landed in the gutter as the cortège turned into New Palace Yard. George's eldest son and successor, Edward VIII, saw it fall and wondered whether it was a bad omen for his new reign.[127] As a mark of respect to their father, George's four surviving sons – Edward, Albert, Henry, and George – mounted the guard, known as the Vigil of the Princes, at the catafalque on the night before the funeral.[128] The vigil was not repeated until the death of George's daughter-in-law, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, in 2002. George V was interred at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, on 28 January 1936.[129] Edward abdicated before the year was out, leaving Albert to ascend the throne as George VI.[130]

Legacy

George V disliked sitting for portraits[17] and despised modern art; he was so displeased by one portrait by Charles Sims that he ordered it to be burned.[131] He did admire sculptor Bertram Mackennal, who created statues of George for display in Madras and Delhi, and William Reid Dick, whose statue of George V stands outside Westminster Abbey, London.[17]

Although he and his wife occasionally toured the British Empire, George preferred to stay at home pursuing his hobbies of stamp collecting and game shooting and lived a life that later biographers would consider dull because of its conventionality.[132] He was not an intellectual: on returning from one evening at the opera he wrote, "Went to Covent Garden and saw Fidelio and damned dull it was."[133] He was earnestly devoted to Britain and its Empire.[134] He explained, "it has always been my dream to identify myself with the great idea of Empire."[135] He appeared hard-working and became widely admired by the people of Britain and the Empire, as well as "the Establishment".[136] In the words of historian David Cannadine, King George V and Queen Mary were an "inseparably devoted couple" who upheld "character" and "family values".[137]

George established a standard of conduct for British royalty that reflected the values and virtues of the upper middle-class rather than upper-class lifestyles or vices.[138] Acting within his constitutional bounds, he dealt skilfully with a succession of crises: Ireland, the First World War, and the first socialist minority government in Britain.[17] He was by temperament a traditionalist who never fully appreciated or approved the revolutionary changes under way in British society.[139] Nevertheless, he invariably wielded his influence as a force of neutrality and moderation, seeing his role as mediator rather than final decision maker.[140]

Titles, honours and arms

As Duke of York, George's arms were the

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Marriage | Their children | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Spouse | |||||

| Edward VIII (later Duke of Windsor) |

23 June 1894 | 28 May 1972 (aged 77) | 3 June 1937 | Wallis Simpson | None | |

| George VI | 14 December 1895 | 6 February 1952 (aged 56) | 26 April 1923 | Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon

|

Elizabeth II | |

| Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon | ||||||

| Mary, Princess Royal | 25 April 1897 | 28 March 1965 (aged 67) | 28 February 1922 | Henry Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood | George Lascelles, 7th Earl of Harewood | |

| The Hon. Gerald Lascelles | ||||||

| Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester | 31 March 1900 | 10 June 1974 (aged 74) | 6 November 1935 | Lady Alice Montagu Douglas Scott

|

Prince William of Gloucester | |

| Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester | ||||||

| Prince George, Duke of Kent | 20 December 1902 | 25 August 1942 (aged 39) | 29 November 1934 | Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark | Prince Edward, Duke of Kent | |

| Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy | ||||||

| Prince Michael of Kent | ||||||

| Prince John | 12 July 1905 | 18 January 1919 (aged 13) | None | None | ||

Ancestry

| Ancestors of George V Princess Louise of Hesse-Kassel | | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15. Princess Charlotte of Denmark | |||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ^

His godparents were the Princess Louis of Hesse and by Rhine (George's aunt, for whom her sister Princess Louise stood proxy).[1]

- ^ Vernon Bogdanor argues that George V played a crucial and active role in the political crisis of August–October 1931, and was a determining influence on Prime Minister MacDonald.[97] Philip Williamson disputes Bogdanor, saying the idea of a national government had been in the minds of party leaders since late 1930 and it was they, not the King, who determined when the time had come to establish one.[98]

References

- ^ The Times (London), Saturday, 8 July 1865, p. 12.

- ^ Clay, p. 39; Sinclair, pp. 46–47

- ^ Sinclair, pp. 49–50

- ^ Clay, p. 71; Rose, p. 7

- ^ Rose, p. 13

- ^ Keene, Donald (2002), Emperor of Japan: Meiji and his world, 1852–1912, Columbia University Press, pp. 350–351

- ^ Rose, p. 14; Sinclair, p. 55

- ^ Rose, p. 11

- ^ Clay, p. 92; Rose, pp. 15–16

- ^ Sinclair, p. 69

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, pp. 250–251

- ^ Rose, pp. 22–23

- ^ Rose, p. 29

- ^ Rose, pp. 20–21, 24

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, pp. 230–231

- ^ Sinclair, p. 178

- ^ , retrieved 1 May 2010 (Subscription required)

- ^ Clay, p. 149

- ^ Clay, p. 150; Rose, p. 35

- ^ Rose, pp. 53–57; Sinclair, p. 93 ff

- ^ Vickers, ch. 18

- ^ Renamed from Bachelor's Cottage

- ^ Clay, p. 154; Nicolson, p. 51; Rose, p. 97

- ^ Harold Nicolson's diary quoted in Sinclair, p. 107

- ^ Nicolson's Comments 1944–1948, quoted in Rose, p. 42

- ^ The Royal Philatelic Collection, Official website of the British Monarchy, archived from the original on 15 April 2012, retrieved 1 May 2010

- ^ Clay, p. 167

- ^ Rose, pp. 22, 208–209

- ^ Rose, p. 42

- ^ Rose, pp. 44–45

- ^ Rose, pp. 43–44

- ^ Bassett, Judith (1987), "'A Thousand Miles of Loyalty': the Royal Tour of 1901", New Zealand Journal of History, 21 (1): 125–138; Oliver, W. H., ed. (1981), The Oxford History of New Zealand, pp. 206–208

- ^ Rose, p. 45

- ^ "No. 27375", The London Gazette, 9 November 1901, p. 7289

- ^ Previous Princes of Wales, Household of HRH The Prince of Wales, archived from the original on 19 April 2020, retrieved 19 March 2018

- ^ Clay, p. 244; Rose, p. 52

- ^ Rose, p. 289

- ^ Sinclair, p. 107

- Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War, Random House, pp. 449–450

- ^ Rose, pp. 61–66

- ^ Rose, pp. 67–68

- ^ King George V's diary, 6 May 1910, Royal Archives, quoted in Rose, p. 75

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 421; Rose, pp. 75–76

- ^ Rose, pp. 82–84

- ISBN 978-0-7546-9930-9, archivedfrom the original on 17 June 2016, retrieved 28 November 2015

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (10 November 2010), "How George V was received by the Irish in 1911", The Telegraph, archived from the original on 18 April 2018

- the Irish Examiner, 11 May 2011, archivedfrom the original on 13 August 2014, retrieved 13 August 2014

- ^ Rose, p. 136

- ^ Rose, pp. 39–40

- ^ Rose, p. 87; Windsor, pp. 86–87

- ^ Rose, p. 115

- ^ Rose, pp. 112–114

- ^ Rose, p. 114

- ^ Rose, pp. 116–121

- ^ Rose, pp. 121–122

- ^ a b Rose, pp. 120, 141

- ^ Hardy, Frank (May 1970), "The King and the constitutional crisis", History Today, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 338–347

- ^ Rose, pp. 121–125

- ^ Rose, pp. 125–130

- ^ Rose, p. 123

- ^ Rose, p. 137

- ^ Rose, pp. 141–143

- ^ Rose, pp. 152–153, 156–157

- ^ Rose, p. 157

- ^ Rose, p. 158

- ^ Nicolson, p. 247

- ^ Nicolson, p. 308

- ^ "No. 30186", The London Gazette, 17 July 1917, p. 7119

- ^ Rose, pp. 174–175

- ^ Nicolson, p. 310

- ^ Clay, p. 326; Rose, p. 173

- ^ Nicolson, p. 301; Rose, pp. 210–215; Sinclair, p. 148

- ^ Rose, p. 210

- ^ Crossland, John (15 October 2006), "British spies in plot to save Tsar", The Sunday Times

- ^ Sinclair, p. 149

- ^ Diary, 25 July 1918, quoted in Clay, p. 344 and Rose, p. 216

- ^ Clay, pp. 355–356

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 511

- ISBN 978-0-87745-898-2

- ^ Rose, p. 294

- from the original on 19 November 2018, retrieved 28 December 2018

- ^ "Archduke Otto von Habsburg", The Daily Telegraph (obituary), London, UK, 4 July 2011, archived from the original on 24 December 2019, retrieved 4 April 2018

- ^ Rose, pp. 347–348

- ^ Nicolson, p. 347; Rose, pp. 238–241; Sinclair, p. 114

- ^ Mowat, p. 84

- ^ Mowat, p. 86

- ^ Mowat, pp. 89–93

- ^ Mowat, pp. 106–107, 119

- S2CID 144979227

- ^ Nicolson, p. 419; Rose, pp. 341–342

- ^ Rose, p. 340; Sinclair, p. 105

- ^ Rose, p. 348

- ^ "Statute of Westminster 1931", legislation.gov.uk, archived from the original on 24 December 2012, retrieved 20 July 2017

- ^ a b Rose, pp. 373–379

- ^

- ^

- ^ Nicolson, pp. 521–522; Owens, pp. 92–93; Rose, p. 388

- ^ Nicolson, pp. 521–522; Rose, p. 388

- ^ Sinclair p. 154

- ^ Sinclair, p. 1

- ISBN 978-0-471-19431-6

- ISBN 978-0-00-215741-4

- ^ Rose, p. 392

- ^ Windsor, pp. 118–119

- ^ Rose, pp. 301, 344

- PMID 29009522.

- ^ Ziegler, pp. 192–196

- ^ Arthur Bigge, 1st Baron Stamfordham, to Alexander Cambridge, 1st Earl of Athlone, 9 July 1929, quoted in Nicolson p. 433 and Rose, p. 359

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 546; Rose, pp. 359–360

- ISBN 978-0-304-35406-1

- ^ Ashley, Mike (1998), The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens, London, UK: Robinson Publishing, p. 699

- ^ Rose, pp. 360–361

- ISBN 978-0-297-79667-1

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 558

- ^ The Times (London), 22 January 1936, p. 7, col. A

- ^ The Times (London), 21 January 1936, p. 12, col. A

- ^ Rose, p. 402

- ^ PMID 11645856

- from the original on 8 October 2016, retrieved 18 September 2016

- ^ PMID 11644545(Subscription required)

- ^ ISBN 9780752483115

- ^ "Doctor murdered Britain's George V", Observer-Reporter, Washington (PA), 28 November 1986, archived from the original on 3 November 2020, retrieved 18 September 2016

- British Pathé, 23 January 1936, archivedfrom the original on 4 May 2016, retrieved 18 September 2016

- ISBN 978-0-19-513931-0, archivedfrom the original on 8 October 2021, retrieved 11 November 2020

- ^ Windsor, p. 267

- ^ The Times (London), Tuesday, 28 January 1936, p. 10, col. F

- ^ Rose, pp. 404–405

- ^ "No. 34350", The London Gazette, 15 December 1936, p. 8117

- ^ Rose, p. 318

- ISBN 0-316-85940-0,

the diary of King George V is the journal of a very ordinary man, containing a great deal more about his hobby of stamp collecting than it does about his personal feelings, with a heavy emphasis on the weather.

- ^ Pierce, Andrew (4 August 2009), "Buckingham Palace is unlikely shrine to the history of jazz", The Telegraph, London, archived from the original on 27 December 2019, retrieved 11 February 2012

- ^ Clay, p. 245; Gore, p. 293; Nicolson, pp. 33, 141, 510, 517

- ^ Harrison, Brian (1996), The Transformation of British Politics, 1860–1995, pp. 320, 337

- ^ Gore, pp. x, 116

- ^ Cannadine, David (1998), History in our Time, p. 3

- ^ Harrison, p. 332; "The King of England: George V", Fortune, p. 33, 1936,

if not himself a characteristic example of the great British middle class, is so like the characteristic examples of that class that there is no perceptible distinction to be made between the two.

- ^ Rose, p. 328

- ^ Harrison, pp. 51, 327

- ^ Velde, François (19 April 2008), "Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family" Archived 17 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Heraldica, retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-85605-469-0

Works cited

- Clay, Catrine (2006), King, Kaiser, Tsar: Three Royal Cousins Who Led the World to War, London: John Murray, ISBN 978-0-7195-6537-3

- Gore, John (1941), King George V: a personal memoir

- , retrieved 1 May 2010 (Subscription required)

- Mowat, Charles Loch (1955), Britain Between The Wars 1918–1940, London: Methuen

- Nicolson, Sir Harold (1952), King George the Fifth: His Life and Reign, London: Constable and Co

- Owens, Edward (2019), "2: 'A man we understand': King George V's radio broadcasts", The Family Firm: monarchy, mass media and the British public, 1932–53, pp. 91–132, JSTOR j.ctvkjb3sr.8

- Pope-Hennessy, James (1959), Queen Mary, London: George Allen and Unwin, Ltd

- ISBN 978-0-297-78245-2

- Sinclair, David (1988), Two Georges: The Making of the Modern Monarchy, London: Hodder and Stoughton, ISBN 978-0-340-33240-5

- Vickers, Hugo (2018), The Quest for Queen Mary, London: Zuleika

- Windsor, HRH The Duke of (1951), A King's Story, London: Cassell and Co

Further reading

- Cannadine, David (2014), George V: The Unexpected King

- Chisholm, Hugh (1922), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 31 (12th ed.)

- Mort, Frank (2019), "Safe for Democracy: Constitutional Politics, Popular Spectacle, and the British Monarchy 1910–1914", Journal of British Studies, 58 (1): 109–141, S2CID 151146689

- Ridley, Jane (2022), George V: Never a Dull Moment, excerpt

- Somervell, D. C. (1936), The Reign of King George V, wide-ranging political, social and economic coverage, 1910–35

- Spender, John A. (1935), "British Foreign Policy in the Reign of HM King George V", International Affairs, 14 (4): 455–479, JSTOR 2603463

External links

- George V at the official website of the British monarchy

- George V at the official website of the Royal Collection Trust

- George V at BBC History

- Portraits of King George V at the National Portrait Gallery, London