Ghassanids

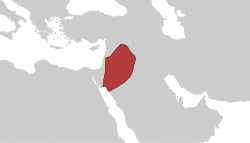

Ghassanids الغساسنة | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 220–638 | |||||||||||

Banner at the Battle of Siffin

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Byzantine Empire | ||||||||||

| Capital | Jabiyah Bosra | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Old Arabic | ||||||||||

| Religion | Christianity (official)[1] | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 220–265 | Jafnah I (first) | ||||||||||

• 632–638 | Jabala ibn al-Ayham (last) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 220 | ||||||||||

• Annexed by Rashidun Caliphate | 638 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Historical Arab states and dynasties |

|---|

|

The Ghassanids,

After settling in the Levant, the Ghassanids became a client state to the Byzantine Empire and fought alongside them against the Sasanian Empire and their Arab vassals, the Lakhmids.[3][6] The lands of the Ghassanids also acted as a buffer zone protecting lands that had been annexed by the Romans against raids by Bedouins.[citation needed]

A few Ghassanids became Muslims following the Muslim conquest of the Levant; most Ghassanids remained Christian and joined Melkite and Syriac communities within what is now Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon.[4]

Traditional genealogy and migration from South Arabia

In the Arab genealogical tradition which developed during the early Islamic period, the Ghassanids were considered a branch of the Azd tribe of South Arabia/Yemen. In this genealogical scheme, their ancestor was Jafna, a son of Amr Muzayqiya ibn Mazin ibn Azd, through whom the Ghassanids were purportedly linked with the Ansar (the Aws and Khazraj tribes of Medina), who were the descendants of Jafna's brother Tha'laba.[7] According to the historian Brian Ulrich, the links between Ghassan, the Ansar, and the wider Azd are historically tenuous, as these groups are almost always counted separately from each other in sources other than post-8th-century genealogical works and the story of the 'Scattering of Azd'.[8] In the latter story, the Azd migrate northward from Yemen and different groups of the tribe split off in different directions, with the Ghassan being one such group.[9]

Per the "Scattering of Azd" story, the Ghassanids eventually settled within the Roman limes.[3][10] The tradition of Ghassanid migration finds support in the Geography of Ptolemy, which locates a tribe called the Kassanitai south of the Kinaidokolpitai and the river Baitios (probably the wadi Baysh). These are probably the people called Casani in Pliny the Elder, Gasandoi in Diodorus Siculus and Kasandreis in Photios I of Constantinople (relying on older sources).[11][12] The date of the migration to the Levant is unclear, but they are believed to have first arrived in the region of Syria between 250 and 300, with later waves of migration circa 400.[3] Their earliest appearance in records is dated to 473, when their chief, Amorkesos, signed a treaty with the Byzantine Empire acknowledging their status as foederati controlling parts of Palestine. He apparently became a Chalcedonian Christian at this time. By the year 510, the Ghassanids were no longer Miaphysites, but Chalcedonian.[13]

Byzantine period

The "Assanite Saracen" chief Podosaces that fought alongside the Sasanians during Julian's Persian expedition in 363 might have been a Ghassanid.[14]

After originally settling in the Levant, the Ghassanids became a

Byzantine–Persian Wars

The Ghassanids fought alongside the Byzantine Empire against the Persian Sasanians and Arab Lakhmids.[6] The lands of the Ghassanids also continually acted as a buffer zone, protecting Byzantine lands against raids by Bedouin tribes. Among their Arab allies were the Banu Judham and Banu Amilah.

The Byzantines were focused more on the East and a long war with the Sasanians was always their main concern. The Ghassanids maintained their rule as the guardian of trade routes, policed Lakhmid tribes and was a source of troops for the imperial army. The Ghassanid king al-Harith ibn Jabalah (reigned 529–569) supported the Byzantines against the Sasanians and was given in 529 by the emperor Justinian I, the highest imperial title that was ever bestowed upon a foreign ruler; also the status of patricians. In addition to that, al-Harith ibn Jabalah was given the rule over all the Arab allies of the Byzantine Empire.[19] Al-Harith was a Miaphysite Christian; he helped to revive the Syrian Miaphysite (Jacobite) Church and supported Miaphysite development despite Orthodox Byzantium regarding it as heretical. Later Byzantine mistrust and persecution of such religious unorthodoxy brought down his successors, Al-Mundhir III ibn al-Harith (reigned 569–582).

The Ghassanids, who had successfully opposed the Lakhmids of

Early Islamic period

Muslim conquest of Syria

The

Umayyad and Abbasid periods

Significant remnants of the Ghassan remained in Syria, residing in Damascus and the city's

When Mu'awiya's grandson, Caliph

The above tribes thereafter formed the

Scholarly families in Damascus

Two Damascene Ghassanid families in particular achieved prominence in early Islamic Syria, those of

Abu Mushir's grandfather, Abd al-A'la, was a hadith scholar and Abu Mushir studied under the famous Syrian scholar Sa'id ibn Abd al-Aziz al-Tanukhi. He became a prominent hadith scholar in Damascus, with special interest in the administrative history of Syria, its local elite's genealogies and local scholars.

Kings

Medieval Arabic authors used the term Jafnids for the Ghassanids, a term modern scholars prefer at least for the ruling stratum of Ghassanid society.[2] Earlier kings are traditional, actual dates highly uncertain.

- Jafnah I ibn Amr (220–265)

- Amr I ibn Jafnah (265–270)

- Tha'labah ibn Amr (270–287)

- al-Harith I ibn Tha'labah (287–307)

- Jabalah I ibn al-Harith I (307–317)

- al-Harith II ibn Jabalah 'ibn Maria' (317–327)

- al-Mundhir I Senior ibn al-Harith II (327–330) with...

- al-Ayham ibn al-Harith II (327–330) and...

- al-Mundhir II Junior ibn al-Harith II (327–340) and...

- al-Nu'man I ibn al-Harith II (327–342) and...

- Amr II ibn al-Harith II (330–356) and...

- Jabalah II ibn al-Harith II (327–361)

- Jafnah II ibn al-Mundhir I (361–391) with...

- al-Nu'man II ibn al-Mundhir I (361–362)

- al-Nu'man III ibn Amr ibn al-Mundhir I (391–418)

- Jabalah III ibn al-Nu'man (418–434)

- al-Nu'man IV ibn al-Ayham (434–455) with...

- al-Harith III ibn al-Ayham (434–456) and...

- al-Nu'man V ibn al-Harith (434–453)

- al-Mundhir II ibn al-Nu'man (453–472) with...

- Amr III ibn al-Nu'man (453–486) and...

- Hijr ibn al-Nu'man (453–465)

- al-Harith IV ibn Hijr (486–512)

- Jabalah IV ibn al-Harith (512–529)

- al-Amr IV ibn Mah'shi (529)

- al-Harith V ibn Jabalah (529–569)

- al-Mundhir III ibn al-Harith (569–581) with...

- Abu Kirab al-Nu'man ibn al-Harith (570–582)

- al-Nu'man VI ibn al-Mundhir (581–583)

- al-Harith VI ibn al-Harith (583)

- al-Nu'man VII ibn al-Harith Abu Kirab (583–?)

- al-Ayham ibn Jabalah (?–614)

- al-Mundhir IV ibn Jabalah (614–?)

- Sharahil ibn Jabalah (?–618)

- Amr IV ibn Jabalah (628)

- Jabalah V ibn al-Harith (628–632)

- Jabalah VI ibn al-Ayham (632–638)

Legacy

The Ghassanids reached their peak under al-Harith V and al-Mundhir III. Both were militarily successful allies of the Byzantines, especially against their enemies the Lakhmids, and secured Byzantium's southern flank and its political and commercial interests in Arabia proper. On the other hand, the Ghassanids remained fervently dedicated to

After the fall of the first kingdom in the 7th century, several dynasties, both Christian and Muslim, ruled claiming to be a continuation of the House of Ghassan.[34] Besides the claim of the Phocid or Nikephorian Dynasty of the Byzantine Empire being related. The Rasulid Sultans ruled from the 13th until the 15th century in Yemen,[35] while the Burji Mamluk Sultans did likewise in Egypt from the 14th to the 16th centuries.[36]

The last rulers to bear the titles of Royal Ghassanid successors were the Christian Sheikhs Al-Chemor in Mount Lebanon ruling the small sovereign principality of Akoura (from 1211 until 1641) and Zgharta-Zwaiya (from 1643 until 1747)[37] from Lebanon.[38][39][40] HIRH Prince Gharios El Chemor of Ghassan Al-Numan VIII as of 2022 is internationally recognized as the head of the Ghassanid dynasty [41][42][43][44] including the UN in 2016 [45][46] and in 2019 was recognized as such by the government of Lebanon by Presidential decree 5,800/2019.[47][48][49][50][51]

See also

- Salīhids

- Rasulids

Notes and references

- Latin: Ghassanidae; Greek: Γασσανίδες, Gassanídes

- ISBN 9780825493638.

- ^ a b Fisher 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Hoberman, Barry (March–April 1983). "The King of Ghassan". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ ISBN 9780674511705.

Late Antiquity - Bowersock/Brown/Grabar.

- ^ "Deir Gassaneh".

- ^ ISBN 9780486203997.

- ^ Ulrich 2019, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Ulrich 2019, p. 13.

- ^ Ulrich 2019, p. 31.

- ISBN 978-90-04-07026-4.

- ^ Cuvigny & Robin 1996, pp. 704–706.

- ^ Bukharin 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Irfan Shahid, 1989, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century.

- ISBN 978-0-19-965452-9.

- ^ Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, vol. 1, Irfan Shahîd, 1995, p. 103

- ^ Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Volume 2 part 2, Irfan Shahîd, pg. 164

- ^ Through the Ages in Palestinian Archaeology: An Introductory Handbook, p. 160, at Google Books

- ^ "History". Sovereign Imperial & Royal House of Ghassan. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014.

- ^ Irfan Shahîd (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, vol. 2, part 1. pp. 51-104

- ^ Athamina 1994, p. 263.

- ^ Athamina 1994, pp. 263, 267–268.

- ^ a b Khalek 2011, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Khalek 2011, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Crone 1980, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Kennedy 2010, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Kennedy 2010, p. 197.

- ^ Kennedy 2010, p. 198.

- ^ Khalek 2011, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Khalek 2011, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Madelung 2000, p. 333.

- ^ Ball 2000, pp. 102–103; Shahîd 1991, pp. 1020–1021.

- ^ Ball 2000, p. 105; Shahîd 1991, p. 1021.

- ^ Ball 2000, pp. 103–105; Shahîd 1991, p. 1021.

- ^ Late Antiquity - Bowesock/Brown/Grabar, Harvard University Press, 1999, p. 469

- ^ Ghassan post Ghassan, Irfan Shahid, Festschrift "The Islamic World - From classical to modern times", for Bernard Lewis, Darwin Press 1989, p. 332

- ^ Ghassan post Ghassan, Irfan Shahid, Festschrift "The Islamic World - From classical to modern times", for Bernard Lewis, Darwin Press 1989, p. 328

- ^ "Info". nna leb.

- ^ "El-Shark Lebanese Newspaper". Elsharkonline.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "مكتبة الشيخ ناصيف الشمر ! – النهار". Annahar.com. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- ^ "كفرحاتا بلدة شمالية متاخمة لزغرتا شفيعها مار ماما".

- ^ "ZENIT: INTERVIEW: Prince 'Dirties Hands' to Help Middle East Christians Have One Concrete Voice". 6 August 2015.

- ^ "Muslim Journal Vol. 46, No. 46, Jul 30, 2021". 30 July 2021.

- ^ "AL-ARAB NEWSPAPER: Gharios, the king of Ghassan in the 21st century" (in Arabic). 12 July 2014.

- ^ "The Jerusalem Post: Global Imams Council builds bridges with all religions". 17 September 2020.

- ^ "ZENIT: INTERVIEW: INTERVIEW: 'I Want to Give a Voice to Those With None'". 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Comité des ONG: Accusée de " politisation ", l'ONG américaine " Committee to Protect Journalists Inc. " privée d'un statut consultatif auprès de l'ECOSOC | UN Press".

- ^ "The Royal House of Ghassan and its continuous official recognition". THE ROYAL HERALD. 22 January 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ Herald, The Royal (3 September 2023). "Understanding the irrefutable official recognition by the Lebanese Government". THE ROYAL HERALD. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ Prince Gharios El Chemor & family received by Lebanese President Michel Aoun, retrieved 3 January 2024

- ^ "عون هنأ ماكرون واستقبل لحام: لبنان وفرنسا سيواصلان العمل معا من اجل الاستقرار في الشرق الاوسط والعالم". annahar.com. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Global Imams Council builds bridges with all religions". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 17 September 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

Bibliography

- Athamina, Khalil (1994). "The Appointment and Dismissal of Khālid b. al-Walīd from the Supreme Command: A Study of the Political Strategy of the Early Muslim Caliphs in Syria". Arabica. 41 (2): 253–272. JSTOR 4057449.

- Ball, Warwick (2000). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-02322-6.

- Bukharin, Mikhail D. (2009). "Towards the Earliest History of Kinda" (PDF). Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 20 (1): 64–80. ]

- ISBN 0-521-52940-9.

- Cuvigny, Hélène; Robin, Christian (1996). "Des Kinaidokolpites dans un ostracon grec du désert oriental (Égypte)". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 6 (2): 697–720.

- ISBN 0-691-05327-8.

- Fisher, Greg (2018). "Jafnids". In Oliver Nicholson (ed.). ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Fowden, Elizabeth Key (1999). The Barbarian Plain: Saint Sergius Between Rome and Iran. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21685-7.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2010). "Syrian Elites from Byzantium to Islam: Survival or Extinction?". In Haldon, John (ed.). Money, Power and Politics in Early Islamic Syria: A Review of Current Debates. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate. pp. 181–199. ISBN 9780754668497.

- Khalek, Nancy (2011). Damascus after the Muslim Conquest: Text and Image in Early Islam. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973651-5.

- Madelung, Wilferd (2000). "Abūʾl-Amayṭar al-Sufyānī". Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam. 24: 327–341.

- Millar, Fergus: "Rome's 'Arab' Allies in Late Antiquity". In: Henning Börm - Josef Wiesehöfer (eds.), Commutatio et Contentio. Studies in the Late Roman, Sasanian, and Early Islamic Near East. Wellem Verlag, Düsseldorf 2010, pp. 159–186.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1965). "Ghassān". In OCLC 495469475.

- ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1995). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-214-5.

- Ulrich, Brian (2019). Arabs in the Early Islamic Empire: Exploring al-Azd Tribal Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-3682-3.