Giorgio Antonucci

Giorgio Antonucci | |

|---|---|

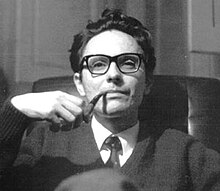

Antonucci in 1975 | |

| Born | 24 February 1933 |

| Died | (aged 84) Florence, Tuscany, Italy |

| Citizenship | Italian |

| Alma mater | University of Florence, University of Siena |

| Known for | criticism of psychiatry, freedom of thought, non-psychiatric approach to psychological suffering, rejection of the involuntary commitment, rejection of the psychiatric diagnosis |

| Awards | Thomas Szasz Award (2005) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychiatry |

| Institutions | Psychiatric hospital Osservanza in Imola (Italy) Psychiatric hospital Luigi Lolli, Imola (Italy) Mental health service in Reggio Emilia (Italy) Centro di Relazioni Umane in Cividale del Friuli (Italy) Psychiatric hospital in Gorizia (Italy) |

| Website | https://giorgioantonucci.org |

Giorgio Antonucci (24 February 1933 – 18 November 2017) was an

Biography

Antonucci was born, on 24 February 1933, in Lucca, Tuscany.[2] In 1963 he studied psychoanalysis with Roberto Assagioli, the founder of psychosynthesis, and began to dedicate himself to psychiatry trying to solve the problems of the patients and avoiding hospitalisation and any kind of coercive method (mechanical, pharmacological, psychological). In 1968 he worked in Cividale del Friuli[3] with Edelweiss Cotti, in a ward of the city hospital that had been opened as an alternative to the mental hospitals, called the Centro di Relazioni Umane [Centre for Human Relations].

In 1969 he worked at the psychiatric hospital in Gorizia, directed by Franco Basaglia.[4][5] From 1970 to 1972 he directed the mental health centre of Castelnuovo nei Monti in the province of Reggio Emilia. From 1973 to 1996 he directed worked in Imola on the dismantling of several wards of the psychiatric hospitals Osservanza and Luigi Lolli. During the earthquake that struck Sicily in 1968 he worked as a physician for the Civil Protection Service of Florence. At the time of his death in 2017 Antonucci lived in Florence and collaborated with the Italian branch of the Citizens Commission on Human Rights, with the Centro di Relazioni Umane[6] and with Radicali Italiani.[7]

Thought on psychiatry

Dacia Maraini: "Regarding the so-called insane persons, what does this new method entail?"

Giorgio Antonucci: "For me it means that insane persons don't exist and that psychiatry must be completely eliminated."— Interview, 1978[8]

In his writings, Antonucci affirmed that theoretically he is close to the humanistic-existential perspective of Carl Rogers, the approaches focused on the critique of psychiatry (Erving Goffman, R. D. Laing, David Cooper and Thomas Szasz[9]) and the critique of the psychiatric institution of Franco Basaglia.

Szasz affirmed to agree with Antonucci on the concept of "person" of the so-called psychiatric patients: "They are, like us, persons in all respects, that can be judged emotionally and in their "human condition"; "mental illness" does not make the patient "less than a man", and it is not necessary to appeal to a psychiatrist to "give them back humanity""[9]. He is the founder of the non-psychiatric approach[1][10][11] to psychological suffering, that is based on the following propositions:

- The involuntary commitment cannot be a scientific and medical approach to suffering, because it is based on violence against the patient's will.

- The ethic of the dialogue is substituted for the ethic of coercion. The dialogue cannot take place unless the individuals recognize themselves as persons in a confrontation among peers.

- The diagnosis is rejected as psychiatric prejudice that impedes to undertake the real psychological work on the suffering of people, due to the contradictions of nature and the conscience and because of the contradictions of society and the conflicts of living together.

- Psychoactive drugs aim to sedate, to drug the person in order to improve the living conditions of the people that look after the psychiatric patient. All the other instruments that damage the person are refused, from the lobotomy to the castration (proposed by some people also in Italy with reference to sexual offenses), and every type of shock.

- In order to criticize the institutions it is necessary to bring into question also the thought that created them.

Antonucci posited that the "essence of psychiatry lies in an ideology of discrimination".[12] He defended a “non-psychiatric thought, which considers psychiatry as an ideology without scientific content, a non-knowledge, whose aim is to annihilate people instead of trying to understand the difficulties of life, both individual and social, in order to defend people, change society and give life to an authentically new culture.”[13]

Giorgio Antonucci and Thomas Szasz

In the words of Thomas Szasz, "Italian psychiatry has been incalculably enriched by Giorgio Antonucci. It is possible to consider him a good psychiatrist (whatever the meaning of the word): and that is true. It is also possible to consider him a good antipsychiatrist (whatever the meaning of the word): and that is just as certain. I prefer to consider him a respectable person that puts the respect for the so-called insane person above the respect for the profession. For that I send him my regards."[10]

Awards

On 26 February 2005 Antonucci received in Los Angeles the Thomas Szasz Humanitarian Award. Szasz said of Antonucci, "His long-standing, courageous, and effective efforts to liberate psychiatric slaves in Italy from their bondage makes him an eminently worthy recipient of CCHR's Thomas Szasz Award."[14]

Works

- I pregiudizi e la conoscenza critica alla psichiatria (preface by Thomas S. Szasz), ed. Coop. Apache – 1986

- Psichiatria ieri ed oggi, Enciclopedia Atlantica (European Book, Milano) – 1989

- Il pregiudizio psichiatrico, Eleuthera – 1989 ISBN 88-85861-10-5

- La nave del paradiso, Spirali – 1990 ISBN 88-7770-296-6

- Freud e la psichiatria, Enciclopedia Atlantica, European Book, Milano – 1990

- Aggressività Composizione in tre tempi in Uomini e lupi, Edizioni Eleuthera – 1990 ISSN 0392-5013

- Psichiatria e cultura, Enciclopedia Atlantica, European Book, Milano – 1991

- Contrappunti, Roma: ISBN 978-8886323062

- Critica al giudizio psichiatrico, ISBN 8889883014

- Il giudice e lo psichiatra, collection Volontà di Eleuthera – volume – Delitto e castigo – 1994 ISSN 0392-5013

- (with Alessio Coppola) Il telefono viola. Contro i metodi della psichiatria, Eleuthera – 1995 ISBN 9788885861602

- Pensieri sul suicidio, Eleuthera – 1996 ISBN 88-85861-75-X

- Il pregiudizio psichiatrico, Eleuthera – 1998 ISBN 9788885861992

- Le lezioni della mia vita. La medicina, la psichiatria, le istituzioni, Spirali – 1999 ISBN 88-7770-536-1

- Pensieri sul suicidio, Eleuthera – 2002 ISBN 9788885060692

- Il cervello. Atti del congresso internazionale Milano, dal 29 novembre al 1º dicembre 2002 (it contains Antonucci's speech at the congress), Spirali – 2004

- Critica al giudizio psichiatrico, ISBN 978-8889883013

- Diario dal manicomio. Ricordi e pensieri, Spirali – 2006 ISBN 978-8877707475

- Igiene mentale e libero pensiero. Giudizio e pregiudizio psichiatrici, publication by the association "Umanità nova", Reggio Emilia – October 2007.

- Foucault e l'antipsichiatria. Intervista a Giorgio Antonucci."Diogene Filosofare Oggi" N. 10 – Anno 2008 – Con «IL DOSSIER: 30 anni dalla legge Basaglia»

- Corpo – "Intervista di Augusta Eniti a Giorgio Antonucci", Multiverso" Università degli studi di Udine, n.07 08 ISSN 1826-6010. 2008

- Conversazione con Giorgio Antonucci edited by Erveda Sansi. Critical Book – I quaderni dei saperi critici – Milano 16.04.2010. S.p.A. Leoncavallo.

- (with other authors) La libertà sospesa, Fefè editore, Roma – 2012 ISBN 978-88-95988-31-3

- (contributions by Giorgio Antonucci and Ruggero Chinaglia) Della Mediazione by Elisa Ruggiero, Aracne – 2013 ISBN 978-88-548-5716-2

- El prejuicio psiquiátrico [Il pregiudizio psichiatrico], introductions by Thomas Szasz and Massimo Paolini, translation and editorial coordination by Massimo Paolini, Katakrak, Pamplona, 2018 – ISBN 978-84-16946-23-5

- Il pregiudizio psichiatrico, with a preface by Thomas Szasz, Ed. Elèuthera, 2020, ISBN 9788833020761

Bibliography

- Dossier Imola e legge 180, Alberto Bonetti, Dacia Maraini, Giuseppe Favati, Gianni Tadolini, Idea books – Milano 1979.

- Antipsykiatri eller Ikke – Psykiatri, Svend Bach, Edizioni Amalie Copenaghen – 1989

- Atlanti della filosofia. Il pensiero anarchico. Alle radici della libertà. Edizioni Demetra – Colognola ai Colli. Verona – December 1997. ISBN 88-440-0577-8.

- Sanità obbligata, Claudia Benatti, preface by Alex Zanotelli, Macro Edizioni, Diegaro di Cesena – October 2004. ISBN 88-7507-567-0

- Le urla dal silenzio. La paura e i suoi linguaggi, Chiara Gazzola, Interviste, Aliberti Editore, Reggio Emilia – 2006. ISBN 88-7424-129-1

- Il 68 visto dal basso. Esercizi di memoria il '68, Giuseppe Gozzini, Asterios editore Trieste – November 2008. ISBN 9788895146171

- Dentro Fuori: testimonianze di ex-infermieri degli ospedali psichiatrici di Imola, edited by Roberta Giacometti, Bacchilega Editori – 2009. ISBN 978-8888775951

- La parola fine. Diario di un suicidio, Roberta Tatafiore, Rizzoli – April 2010.ISBN 978-88-17-03992-5

- La mia mano destra, Donato Salvia, Bonfirraro Editore, Barrafranca-Enna – May 2011 ISBN 978-88-6272-030-4

- La grande festa, ISBN 978-88-17-05548-2

- L'inganno psichiatrico, Roberto Cestari, Libres s.r.l. Casa Editrice, Milano – May 2012 ISBN 978-88-97936-00-8

- Che cos'è l'Antipsichiatria? – Storia della nascita del movimento di critica alla psichiatria, Francesco Codato Ed. Psiconline, October 2013, ISBN 978-88-98037-27-8

- La Repubblica dei matti, ISBN 978-88-07-11137-2

- Encyclopedia of Theory and Practice in Psychotherapy and Counseling, José A. Fadul, Lulu Press Inc., London, ISBN 978-1-312-07836-9

- The Man Who Closed the Asylums: Franco Basaglia and the Revolution in Mental Health Care, ISBN 9781781689264

- Le radici culturali della diagnosi, Pietro Barbetta, Meltemi Editore srl, 2003, ISBN 978-88-8353-223-8

- La chiave comune. Esperienze di lavoro presso l'ospedale psichiatrico Luigi Lolli di Imola, Giovanni Angioli, ED. La Mandragola Editrice, 11/2016. ISBN 9788875865023

- Forse non sarà domani: Invenzioni a due voci su Luigi Tenco, Mario Campanella, Gaspare Palmieri, LIT EDIZIONI, 2017, ISBN 9788862319669

- Giorgio Antonucci: una vida por la liberación de quienes no tienen poder, Massimo Paolini, El Salto, 1 December 2017

- Giorgio Antonucci: a life for the liberation of the powerless, Massimo Paolini, Open Democracy, 6 December 2017

- Recomponer la imagen, cuestionando el poder [preface to the book ‘El prejuicio psiquiátrico’], Massimo Paolini, Perspectivas anómalas | ciudad · arquitectura · ideas, 2018

- Críticas y alternativas en psiquiatría, Rafael Huertas et al., Los Libros de la Catarata, 2018, ISBN 9788490975220

- Conversación entre Guillermo Vera y Massimo Paolini acerca de la publicación del libro El prejuicio psiquiátrico in Perspectivas anómalas | ciudad · arquitectura · ideas, 2019

- Welcome to Arkham Asylum: Essays on Psychiatry and the Gotham City Institution, Sharon Packer, M.D., Daniel R. Fredrick, McFarland, 2019

- The Italian Psychiatric Experience, Alessandro De Risio, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2019

- Critical Neuroscience and Philosophy: A Scientific Re-Examination of the Mind-Body Problem, David Låg Tomasi, Springer Nature, 2020

- Madness in Contemporary British Theatre. Resistances and Representations, Jon Venn, Springer, 2021, ISBN 978-3-030-79781-2

- A Critical History of Psychotherapy, Volume 2: From the Mid-20th to the 21st Century, Marco Innamorati, Renato Foschi, United Kingdom, Taylor & Francis, 2022

- La historia de los vertebrados, García Puig, Mar, Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial España, 2023, ISBN 978-84-397-4170-1

- “(Sobre)vivencias de la psiquiatría”: una aproximación a las subjetividades de la violencia institucional y los activismos locos, Edurne de Juan Franco, Ponto Urbe [Online], 29 | 2021, URL: http://journals.openedition.org/pontourbe/11029; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/pontourbe.11029

References

- ^ a b I pregiudizi e conoscenza critica alla psichiatria (in Italian). Preface by T. Szasz. Apache. 1986. Archived from the original on 2018-03-15. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Antonucci, Giorgio. "Giorgio Antonucci".

- ^ "Edelweiss Cotti e Giorgio Antonucci a Cividale del Friuli – Foto" (in Italian). Centro di Relazioni Umane. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2014-07-27.

- ISBN 9788854132658.

- ISBN 9788872851357.

- ^ "Centro di Relazioni Umane » Chi Siamo". Archived from the original on 2024-01-01. Retrieved 2024-01-01.

- ^ "Radicali Italiani". 4 April 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "Dacia Maraini intervista Giorgio Antonucci" [Dacia Maraini interviews Giorgio Antonucci]. La Stampa (in Italian). 26 July 1978 and 29–30 December 1978. Archived from the original on 2013-04-13. Retrieved 2014-07-27.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b "Centro di Relazioni Umane » Blog Archive » Prefazione di Thomas Szasz a "Il pregiudizio psichiatrico" di Giorgio Antonucci". centro-relazioni-umane.antipsichiatria-bologna.net. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2020-12-23.

- ^ ISBN 88-85861-10-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

- ^ "Thomas Szasz Award". Archived from the original on 2014-10-16. Retrieved 2014-10-10.

- ISBN 9781781689264.

- ^ Paolini, Massimo (2017). Giorgio Antonucci: a life for the liberation of the powerless. Open Democracy.

- ^ "The Legacy Of Giorgio Antonucci— Abolishing Coercive Psychiatry To Achieve Humane Mental Health Care". CCHR International. Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

Interviews

- Periódico Diagonal nº 250: Antonucci: La locura no tiene ningún significado filosófico, interview to Giorgio Antonucci by Massimo Paolini (see 'External links'). The interview has been republished in CTXT nº 28, Infolibre and Viento Sur.

- Psichiatria e potere, interview to Giorgio Antonucci by Moreno Paulon, in «A Rivista Anarchica», 46, No. 408, June 2016.

External links

- Premio Giorgio Antonucci

- Giorgio Antonucci interviewed on Vimeo (Italian with Spanish subtitles)

- Giorgio Antonucci interviewed on YouTube (Italian with Spanish subtitles)

- Giorgio Antonucci speaks about Franco Basaglia (Italian)

- Giorgio Antonucci speaks about psychiatry (Italian)

- Giorgio Antonucci on ADHD (Italian)

- Interview to Giorgio Antonucci (Italian)

- Giorgio Antonucci speaks about Thomas Szasz (Italian)

- Giorgio Antonucci. Il pregiudizio psichiatrico | Full text of the book (Italian)

- Gli occhi non li vedono (English subtitles)

- Giorgio Antonucci interviewed on Periódico Diagonal and Perspectivas anómalas | ciudad · arquitectura · ideas (Spanish)

- The Man Who Closed the Asylums: Franco Basaglia and the Revolution in Mental Health Care, review by Dr Peter Barham, Wellcome Unit for the History of Medicine, University of Oxford

- UK Parliament, Memorandum from the Citizens Commission on Human Rights (DMH 291)

- Università La Sapienza, Rome, Interview to Giorgio Antonucci (audio, Italian)

![]() Media related to Giorgio Antonucci at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Giorgio Antonucci at Wikimedia Commons