Gloss (annotation)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

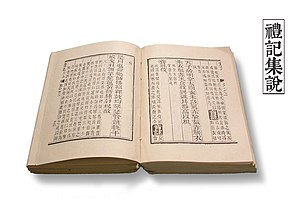

A gloss is a brief notation, especially a marginal or interlinear one, of the meaning of a word or wording in a text. It may be in the language of the text or in the reader's language if that is different.

A collection of glosses is a

Glosses were originally notes made in the margin or between the lines of a text in a classical language; the meaning of a word or passage is explained by the gloss. As such, glosses vary in thoroughness and complexity, from simple marginal notations of words one reader found difficult or obscure, to interlinear translations of a text with cross references to similar passages. Today parenthetical explanations in scientific writing and technical writing are also often called glosses. Hyperlinks to a glossary sometimes supersede them.

Etymology

Starting in the 14th century, a gloze in the English language was a marginal note or explanation, borrowed from French glose, which comes from medieval Latin glōsa, classical glōssa, meaning an obsolete or foreign word that needs explanation.[1] Later, it came to mean the explanation itself. The Latin word comes from Greek γλῶσσα 'tongue, language, obsolete or foreign word'.[2][3] In the 16th century, the spelling was refashioned as gloss to reflect the original Greek form more closely.[4]

In theology

Glosses and other marginal notes were a primary format used in medieval Biblical

In law

In the medieval legal tradition, the glosses on

In literature

A gloss, or glosa, is a verse in traditional

In philology

Glosses are of some importance in

In linguistics

In linguistics, a simple gloss in running text may be marked by quotation marks and follow the transcription of a foreign word. Single quotes are a widely used convention.[6] For example:

- A Cossacklongboat is called a chaika 'seagull'.

- The moose gains its name from the Algonquian mus or mooz ('twig eater').

A longer or more complex transcription may rely upon an interlinear gloss. Such a gloss may be placed between a text and its translation when it is important to understand the structure of the language being glossed, and not just the overall meaning of the passage.

Glossing sign languages

Sign languages are typically transcribed word-for-word by means of a gloss written in the predominant oral language in all capitals; for example, American Sign Language and Auslan would be written in English. Prosody is often glossed as superscript words, with its scope indicated by brackets.

[I LIKE]NEGATIVE [WHAT?]RHETORICAL, GARLIC.

"I don't like garlic."

Pure fingerspelling is usually indicated by hyphenation. Fingerspelled words that have been lexicalized (that is, fingerspelling sequences that have entered the sign language as linguistic units and that often have slight modifications) are indicated with a hash. For example, W-I-K-I indicates a simple fingerspelled word, but #JOB indicates a lexicalized unit, produced like J-O-B, but faster, with a barely perceptible O and turning the "B" hand palm side in, unlike a regularly fingerspelled "B".

References

- Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, s.v.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, First Edition, s.v.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, First Edition, s.v.

- ^ Black's Law Dictionary, 7th ed.

- ^ Campbell, Lyle (1998). Historical Linguistics: An Introduction (1 ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. xvii.

Further reading

- Meinolf Schumacher: "…der kann den texst und och die gloß. Zum Wortgebrauch von 'Text' und 'Glosse' in deutschen Dichtungen des Spätmittelalters." In 'Textus' im Mittelalter. Komponenten und Situationen des Wortgebrauchs im schriftsemantischen Feld, edited by Ludolf Kuchenbuch and Uta Kleine, 207–27, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006 (PDF).

External links

The dictionary definition of gloss at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of gloss at Wiktionary