Good Luck Flag

The Good Luck Flag (寄せ書き日の丸, yosegaki

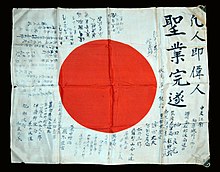

The name 'hinomaru' is taken from the name for the flag of Japan, also known as hinomaru, which translates literally as "circular sun". When yosegaki hinomaru were signed by friends and relatives, the text written on the flag was generally written in a vertical formation radiating out from the central red circle, resembling the sun's rays. This appearance is referenced in the term 'yosegaki' (lit., "collection of writing"), meaning that the term 'yosegaki hinomaru' can be interpreted as a "collection of writing around the red sun", describing the appearance of text radiating outwards from the circle in the centre of the flag.[2]

History

The hinomaru yosegaki was traditionally presented to a man prior to his induction into the Japanese armed forces or before his deployment. The relatives, neighbors, friends, and co-workers of the person receiving the flag would write their names, good luck messages, exhortations, or other personal messages onto the flag in a formation resembling rays dissipating from the sun, though text was also written on any available space if the flag became crowded with messages.[2] On some occasions, small caricatures or cartoons were added to the flag. In rare instances, elaborate and impressive art might also be placed on the flag. Sometimes good luck flags were decorated with images of black and white or colorful tigers.[2] [3]

Hinomaru normally featured some kind of exhortation written across the top of the white field, such as bu-un chō-kyu (武運長久, "May your military fortunes be long lasting"); other typical decoration includes medium-sized characters along the right or left vertical margin of the flag, typically the name of the man receiving the flag, and the name of the individual or organization presenting it to him. The text written on the flag was commonly applied with a calligraphy brush and ink. While it was normally the custom to sign only around the red center of the flag, some examples may be found with characters written upon the red center as well.[2]

The origin of the custom of writing on flags is unclear, with some debate as to the time period when the custom first began. Some sources indicate that signed flags became part of a soldier's possessions, alongside a "

For the military man stationed far away from home and loved ones, the hinomaru yosegaki offered communal hopes and prayers to the owner every time the flag was unfolded. It was believed that the flag, with its many signatures and slogans, would provide a combined force or power to see its owner through tough times, as well as reminding the soldier of his duties in the war, with the implication that the performance of that duty meant that the warrior was not expected to return home from battle. Often, departing servicemen would leave behind clipped fingernails and hair, so that his relatives would have something of him in which to hold a funeral.[2]

The belief of self-sacrifice was central to Japanese culture during World War II, forming much of wartime sentiment. It was culturally believed that great honour was brought upon the family of those whose sons, husbands, brothers and fathers died in service to the country and the Emperor, and that in doing one's duty, any soldier, sailor or aviator would offer up his life freely.[2] As part of the cultural samurai or bushido (way of the warrior) code, this worldview was brought forward into twentieth century Japan from the previous centuries of feudal Japan, and was impressed upon twentieth century soldiers, most of whom descended from non-samurai families.

U.S. veterans' accounts

In

Effort to return flags

The OBON SOCIETY (formerly OBON 2015) is a non-profit affiliate organization with a mission to return hinomaru to their families in Japan.[7][8][9]

The society's work has been recognized by Japan's Minister for Foreign Affairs as an "important symbol of reconciliation, mutual understanding, and friendship between our two countries".[10] As of 2022[update], the society has returned more than 400 flags, and has more than 400 other flags they are currently working on returning.[11][12] On 15 August 2017, the society arranged for Marvin Strombo, a 93-year-old WWII Veteran, to travel back to Japan to return the flag he took to the family of the man who made it.[7][13] The effort to return the flags is widely seen as a humanitarian act providing closure for family members.[13][14][15][16][17][18][19]

Preservation and restoration

The United States'

Modern use

In modern times, yosegaki hinomaru are still used, with the tradition of signing the hinomaru as a good luck charm continuing, though in a limited fashion. The yosegaki hinomaru is often shown at international sporting events to support the national Japanese team.[21] The yosegaki (寄せ書き, "group effort flag") is used for campaigning soldiers,[22] athletes, retirees, transfer students and for friends. In modern Japan, it is given as a present to a person at a send-off party, for athletes, a farewell party for colleagues or transfer students, for graduation and retirement. After natural disasters such as the 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake and tsunami, people commonly write notes on a yosegaki hinomaru to show support. The trend of yosegaki had recently spread to flags of other countries with documented cases of writings on the flag of Brazil, the flag of Canada, the flag of the Czech Republic, the flag of Iran, the flag of Mongolia and the flag of the United States.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

References

- ^ Gary Nila and Robert Rolfe, Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces 2006 Osprey Publishing

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bortner 2008.

- ^ Bortner 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Sid You'll Be Sor-ree, 2010, Valor Studios, INC.

- Presidio PressTrade Paperback Edition

- Monroe, MI. Archived from the originalon 24 March 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Our Mission". Obonsociety.org. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "English". Obon2015.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "Returning Yosegaki Hinomaru". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "OBON SOCIETY Recognized for its Contributions to Japan-U.S. Relations by Japan's Minister for Foreign Affairs" (PDF). Seattle.us.emb-japan.go.jp. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "OBON SOCIETY : Flags OBONソサエティ 日章旗". Obon2015.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "As we celebrate Victory Day today, here's what it means to me". The Providence Journal. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ a b "Former US Marine returns a flag he took from a fallen Japanese soldier during WWII". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ "The flags of their fathers". CBS News. 29 May 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Kim Briggeman (13 March 2017). "WWII vet hopes Japanese flag can be given to owner's family". The Astorian. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- Albany Democrat Herald. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Aging U.S. Veterans Seek To Return Captured WWII Flags To Japan". Nenewsnetwork.org. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ Agency, Air Force ISR (25 April 2014). "The miraculous return of a hinomaru yosegaki". Abc.net.au. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Admiral Returns Flag to Japan". Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ "The War | The National WWII Museum | New Orleans". Nationalww2museum.org. 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Takenaka 2003, p. 101

- ^ "西宮市立郷土資料館の企画展示". Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "Asgari retained as Iran taekwondo coach despite medal-free Tokyo 2020 Olympics". Insidethegames.biz. 26 September 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "【人生変わる!】トロント留学がおすすめな5つの理由【実証済みです】 – オースにジャパ!". Blog-slow-life.net. 27 August 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "巻田先生無事帰国 – 拓殖大学学友会". Takushoku-alumni.jp. 18 March 2010. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "exist†trace Mallyさんご来店!! – リトルハーツ仙台スタッフブログ". Littlehearts.jp. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ 静岡新聞社 (15 July 2021). "モンゴル柔道頑張れ 伊豆の国 子どもら寄せ書き|あなたの静岡新聞". At-s.com. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "チェコのパラ選手とオンライン交流 韮崎の小学生:朝日新聞デジタル". Asahi.com. 27 August 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

Further reading

- Bortner, Michael A. (2008). Imperial Japanese Good Luck Flags and One-Thousand Stitch Belts. Schiffer Military Books. ISBN 978-0764329272.

- Bortner, Michael A. (2021). Imperial Japanese Tiger Art Good Luck Flags of World War Two. Elm Grove Publishing. ISBN 978-1943492572.

- Takenaka, Yoshiharu (2003). 知っておきたい国旗・旗の基礎知識 [Flag basics you should know] (in Japanese). Gifu Shimbun. ISBN 4-87797-054-1.