Goodpasture syndrome

| Goodpasture syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Goodpasture's syndrome, Goodpasture disease, Goodpasture's disease, anti–glomerular basement membrane disease, anti–glomerular basement membrane antibody disease, anti-GBM disease, anti-GBM antibody disease |

PAS stain | |

| Specialty | Nephrology, pulmonology, immunology |

Goodpasture syndrome (GPS), also known as anti–glomerular basement membrane disease, is a

The disease was first described by an American pathologist

Signs and symptoms

The anti–

Cause

While the exact cause is unknown, the genetic predisposition to GPS involves the

Pathophysiology

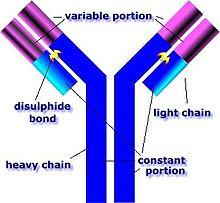

GPS is caused by abnormal

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of GPS is often difficult, as numerous other diseases can cause the various manifestations of the condition and the condition itself is rare.[16] The most accurate means of achieving the diagnosis is testing the affected tissues by means of a biopsy, especially the kidney, as it is the best-studied organ for obtaining a sample for the presence of anti-GBM antibodies.[16] On top of the anti-GBM antibodies implicated in the disease, about one in three of those affected also has cytoplasmic antineutrophilic antibodies in their bloodstream, which often predates the anti-GBM antibodies by about a few months or even years.[16] The later the disease is diagnosed, the worse the outcome is for the affected person.[10]

In addition, if there is substantial suspicion of the disease, serologic testing for ELISA assay is usually done by looking for alpha3 NC1 domain area of collagen IV in order to avoid false positives.[17]

Treatment

The major mainstay of treatment for GPS is

Prognosis

With treatment, the five-year survival rate is >80% and fewer than 30% of affected individuals require long-term dialysis.[10] A study performed in Australia and New Zealand demonstrated that in patients requiring renal replacement therapy (including dialysis) the median survival time is 5.93 years.[10] Without treatment, virtually every affected person will die from either advanced kidney failure or lung hemorrhages.[10]

Epidemiology

GPS is rare, affecting about 0.5–1.8 per million people per year in Europe and Asia.[10] It is also unusual among autoimmune diseases in that it is more common in males than in females and is also less common in blacks than whites, but more common in the Māori people of New Zealand.[10] The peak age ranges for the onset of the disease are 20–30 and 60–70 years.[10]

See also

References

- ^ "Goodpasture Syndrome". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 19 November 2019. Retrieved 2020-12-05.

- PMID 30621605.

- ^ "COL4A3 gene".

- S2CID 71773779.

- S2CID 40175400.

- ^ a b c Kathuria, P; Sanghera, P; Stevenson, FT; Sharma, S; Lederer, E; Lohr, JW; Talavera, F; Verrelli, M (21 May 2013). Batuman, C (ed.). "Goodpasture Syndrome Clinical Presentation". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Schwarz, MI (November 2013). "Goodpasture Syndrome: Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage and Pulmonary-Renal Syndrome". Merck Manual Professional. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- PMID 29083697. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ "Goodpasture syndrome | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-11-23. Retrieved 2020-12-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kathuria, P; Sanghera, P; Stevenson, FT; Sharma, S; Lederer, E; Lohr, JW; Talavera, F; Verrelli, M (21 May 2013). Batuman, C (ed.). "Goodpasture Syndrome". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ "Goodpasture Syndrome". 19 November 2019.

- ^ "Goodpasture Syndrome". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- ^ Marques, C., et al. (2020). Review on anti-glomerular basement membrane disease or Goodpasture's syndrome. The Journal of Internal Medicine, 41(1), 14-20.

- ^ Greco, A., et al. (2015). Goodpasture's syndrome: A clinical update. Autoimmunity Reviews, 14 (3), 246-253.

- ^ Borza, D., et al. (2003). Pathogenesis of Goodpasture syndrome: a molecular perspective. Seminars in Nephrology, 23(6), 522-531.

- ^ a b c Kathuria, P; Sanghera, P; Stevenson, FT; Sharma, S; Lederer, E; Lohr, JW; Talavera, F; Verrelli, M (21 May 2013). Batuman, C (ed.). "Goodpasture Syndrome Workup". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- PMID 29083697. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Kathuria, P; Sanghera, P; Stevenson, FT; Sharma, S; Lederer, E; Lohr, JW; Talavera, F; Verrelli, M (21 May 2013). Batuman, C (ed.). "Goodpasture Syndrome Treatment & Management". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

External links

- GBM antibodies: immunofluorescence image Archived 2007-03-22 at the Wayback Machine