Barosaurus

| Barosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton in rearing posture with a juvenile Kaatedocus siberi, American Museum of Natural History

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Diplodocoidea |

| Family: | †Diplodocidae |

| Genus: | †Barosaurus Marsh, 1890 |

| Species: | †B. lentus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Barosaurus lentus Marsh, 1890

| |

Barosaurus (

The composite term Barosaurus comes from the Greek words barys (βαρυς) meaning "heavy" and sauros (σαυρος) meaning "lizard", thus "heavy lizard".

Description

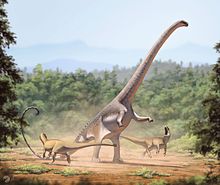

Barosaurus was an enormous animal, with some adults measuring about 25–27 m (82–89 ft) in length and weighing about 12–20

Sauropod skulls are rarely preserved, and scientists have yet to discover a Barosaurus skull. Related diplodocids like Apatosaurus and Diplodocus had long, low skulls with peg-like teeth confined to the front of the jaws.[10]

Most of the distinguishing skeletal features of Barosaurus were in the

The limb bones of Barosaurus were virtually indistinguishable from those of Diplodocus.

Classification and systematics

Barosaurus is a member of the sauropod family Diplodocidae, and sometimes placed with Diplodocus in the subfamily Diplodocinae.[5] Diplodocids are characterized by long tails with over 70 vertebrae, shorter forelimbs than other sauropods, and numerous features of the skull. Diplodocines like Barosaurus and Diplodocus have slenderer builds and longer necks and tails than apatosaurines, the other subfamily of diplodocids.[9][10][5]

Below is a cladogram of Diplodocinae after Tschopp, Mateus, and Benson (2015).[12]

| Diplodocinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The

Discovery, naming, and history

The first Barosaurus remains were discovered in the

After the turn of the 20th century, Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Natural History sent fossil hunter Earl Douglass to Utah to excavate the Carnegie Quarry in the area now known as Dinosaur National Monument. Four neck vertebrae, each 1 meter (3 feet) long, were collected in 1912 near a specimen of Diplodocus, but a few years later, William Jacob Holland realized they belonged to a different species.[9] Meanwhile, the type specimen of Barosaurus had finally been prepared at Yale in the winter of 1917 and was fully described by Richard Swann Lull in 1919.[22] Based on Lull's description, Holland referred the vertebrae (CM 1198), along with a second partial skeleton found by Douglass in 1918 (CM 11984), to Barosaurus. This second Carnegie specimen remains in the rock wall at Dinosaur National Monument and was not fully prepared until the 1980s.[9]

The most complete specimen of Barosaurus lentus was excavated from the Carnegie Quarry in 1923 by Douglass, now working for the

More recently, more vertebrae and a pelvis were recovered in South Dakota. This material (SDSM 25210 and 25331) is stored in the collection of the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City.[11]

Darren Naish has noted a common error in books of the late 20th century to depict Barosaurus as a kind of brachiosaur-like short tailed sauropod with raphes on its neck and body, and often curving the upper half of its neck downwards into a U-shape, citing it as an example of a Palaeoart meme.[23][24] This originated with a drawing by Robert Bakker in a 1968 article, in which two Barosaurus appeared to have short tails due to a mix of foreshortening and one obscuring the other.

In 2007, paleontologist David Evans was flying to the U.S. Badlands when he discovered reference to a Barosaurus skeleton (ROM 3670) in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where he had recently become a curator. Earl Douglass had excavated this specimen at the Carnegie Quarry in the early 20th century; the ROM acquired it in a 1962 trade with the Carnegie Museum. The specimen was never exhibited and remained in storage until its rediscovery by David Evans 45 years later. He returned to Toronto and searched the storage areas and found many fragments, large and small, of the skeleton. It is now a centrepiece of the ROM's dinosaur exhibit, in the James and Louise Temerty Galleries of the Age of Dinosaurs.[25] At almost 27.5 meters (90 feet) long, the specimen is the largest dinosaur ever to be mounted in Canada.[26] The specimen is about 40% complete. As a skull of Barosaurus has never been found, the ROM specimen wears the head of a Diplodocus.[27] Each bone is mounted on a separate armature so that it can be removed from the skeleton for study and then replaced without disturbing the rest of the skeleton. (See video "Dino Workshop" at reference.)[28] In the rush to put the dinosaur on exhibit within ten weeks of its delivery to Research Casting International in 2500 pieces, not all of the skeletal fragments were mounted. In addition, more bones labeled ROM 3670 are still being found in storage. In future, more may be added to the specimen and it may turn out to be the most complete known.' (See video "Dino Assembly" at reference.)[28] The ROM specimen is nicknamed "Gordo" after Gordon Edmunds, the museum curator who arranged for the skeleton to be brought to the ROM, and who had hoped to display it fully but was unable to.[26][29][30] John McIntosh believes that the ROM's skeleton is the same individual represented by four neck vertebrae labeled "CM 1198" in the collection of the Carnegie Museum.[9]

Discoveries in Africa

In 1907,

Paleobiology

Feeding

The structure of the cervical vertebrae of Barosaurus allowed for a significant degree of lateral flexibility in the neck, but restricted vertical flexibility. This suggests a different feeding style for this genus when compared to other diplodocids.[38] Barosaurus swept its neck in long arcs at ground level when feeding, which resembled the strategy that was first proposed by John Martin in 1987.[39] The restriction in vertical flexibility suggests that Barosaurus did not primarily feed on vegetation that was high off the ground.

Paleoecology

Barosaurus remains are limited to the

The Morrison Formation was deposited in

The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs such as

Assistant Curator David Evans mounted the ROM specimen conservatively, with a relatively low head to give the dinosaur moderate blood pressure.[27] The extremely long neck, 10 meters (30 feet) may have developed to enable Barosaurus to feed over a wide area without moving around; it may also have enabled the dinosaurs to radiate excess body heat. Evans suggests that sexual selection might have favored those with longer necks. (See video "Neck Impossible" at reference.)[28]

References

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- S2CID 53446536.

- PMID 24204747.

- ^ Paul, G.S., 2016, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd edition, Princeton University Press p. 213

- ^ a b c d e Lovelace, David M.; Hartman, Scott A.; Wahl, William R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny" (PDF). Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 65 (4): 527–544. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ "The size of the BYU 9024 animal". svpow.com. June 16, 2019. Archived from the original on April 16, 2022.

- ISBN 9780691190693.

- ^ Curtice, Brian (November 1–5, 2021). "New Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry Supersaurus vivianae (Jensen 1985) axial elements provide additional insight into its phylogenetic relationships and size, suggesting an animal that exceeded 39 meters in length" (PDF). The Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Virtual Meeting conference Program. p. 92. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 8, 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-253-34542-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ a b Foster, John R. (1996). "Sauropod dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Black Hills, South Dakota and Wyoming". Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming. 31 (1): 1–25. Archived from the original on June 21, 2010.

- ^ PMID 25870766.

- hdl:2027.42/73066.

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Rinehart, Larry A.; Heckert, Andrew B.; Herne, Matthew C.; Hunt, Adrian P.; Foster, John R.; Sullivan, Robert M. (2006). "Taxonomic status of Seismosaurus hallorum, a Late Jurassic sauropod dinosaur from New Mexico". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 149-161.

- ^ S2CID 86119682.

- S2CID 129739733.

- S2CID 9646734.

- S2CID 131403178.

- ^ Marsh, O.C. (1896). "The dinosaurs of North America". United States Geological Survey, 16th Annual Report, 1894-95. 55: 133–244.

- S2CID 128770034.

- .

- ^ a b Lull, Richard S. (1919). "The sauropod dinosaur Barosaurus Marsh: redescription of the type specimens in the Peabody Museum, Yale University". Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. 6: 1–42.

- ^ Naish, Darren (February 10, 2017). "Palaeoart Memes and the Unspoken Status Quo in Palaeontological Popularization". Scientific American. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- doi:10.26879/145.

- ^ "Massive Barosaurus skeleton discovered at the ROM" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. November 13, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ a b Royal Ontario Museum. ROM Channel: Constructing the Barosaurus. Added 2012-08-28. Accessed 2012-12-11.

- ^ a b National Geographic, Museum Secrets, Episode 3: Royal Ontario Museum, Segment "Lost Dinosaur" Archived July 30, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Broadcast December 10, 2012.

- ^ a b c National Geographic, Museum Secrets, Episode 3: Royal Ontario Museum, Segment "Lost Dinosaur". Video clips. Archived July 30, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Broadcast December 10, 2012.

- ^ Anthony Reinhardt. A monster task - putting Gordo together, The Globe and Mail, November 29, 2007.

- ^ Zain Ahmed. Gordo the Barosaurus. Atlas Obscura. March 15, 2021.

- ^ Fraas, Eberhard (1908). "Ostafrikanische Dinosaurier". Palaeontographica. 55: 105–144.

- ^

Seeley, Harry G.(1869). Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria and Reptilia, from the Secondary system of strata arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell and Co. pp. 143pp.

- ^ Sternfeld, Richard (1911). "Zur Nomenklatur der Gattung Gigantosaurus Fraas". Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin. 1911: 398.

- ^ Janensch, Werner (1922). "Das Handskelett von Gigantosaurus robustus und Brachiosaurus brancai aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas". Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie. 1922: 464–480.

- ^ Wild, Rupert (1991). "Janenschia n. g. robusta (E. Fraas 1908) pro Tornieria robusta (E. Fraas 1908) (Reptilia, Saurischia, Sauropodomorpha)". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde. Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie). 173: 1–4.

- ISSN 1012-0750.

- .

- .

- ^ Martin, John. 1987. Mobility and feeding of Cetiosaurus (Saurischia, Sauropoda) – why the long neck? pp. 154–159 in P. J. Currie and E. H. Koster (eds), Fourth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems, Short Papers. Boxtree Books, Drumheller (Alberta). 239 pages.

- ^ .

- Kirkland, James I. (eds.). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22 (1-4): 235-260. Archived from the original(PDF) on August 24, 2007. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- .

- .

- Kirkland, James I.(eds.). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22 (1-4): 283-296.

- .

- ISBN 978-0253348708.

- ^ Foster, John R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

Books:

- McIntosh (2005). "The Genus Barosaurus (ISBN 978-0-253-34542-4.