Gram stain

Gram stain (Gram staining or Gram's method), is a method of staining used to classify bacterial species into two large groups: gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria. It may also be used to diagnose a fungal infection.[1] The name comes from the Danish bacteriologist Hans Christian Gram, who developed the technique in 1884.[2]

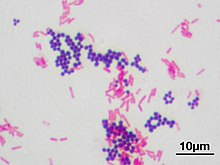

Gram staining differentiates bacteria by the chemical and physical properties of their cell walls. Gram-positive cells have a thick layer of peptidoglycan in the cell wall that retains the primary stain, crystal violet. Gram-negative cells have a thinner peptidoglycan layer that allows the crystal violet to wash out on addition of ethanol. They are stained pink or red by the counterstain,[3] commonly safranin or fuchsine. Lugol's iodine solution is always added after addition of crystal violet to strengthen the bonds of the stain with the cell membrane.

Gram staining is almost always the first step in the identification of a bacterial group. While Gram staining is a valuable diagnostic tool in both clinical and research settings, not all bacteria can be definitively classified by this technique. This gives rise to gram-variable and gram-indeterminate groups.

History

The method is named after its inventor, the Danish scientist Hans Christian Gram (1853–1938), who developed the technique while working with Carl Friedländer in the morgue of the city hospital in Berlin in 1884. Gram devised his technique not for the purpose of distinguishing one type of bacterium from another but to make bacteria more visible in stained sections of lung tissue.[4] He published his method in 1884, and included in his short report the observation that the typhus bacillus did not retain the stain.[5]

Uses

Gram staining is a

Some organisms are gram-variable (meaning they may stain either negative or positive); some are not stained with either dye used in the Gram technique and are not seen.

Medical

Gram stains are performed on body fluid or biopsy when infection is suspected. Gram stains yield results much more quickly than culturing, and are especially important when infection would make an important difference in the patient's treatment and prognosis; examples are cerebrospinal fluid for meningitis and synovial fluid for septic arthritis.[9][10]

Staining mechanism

Gram-positive bacteria have a thick mesh-like cell wall made of peptidoglycan (50–90% of cell envelope), and as a result are stained purple by crystal violet, whereas gram-negative bacteria have a thinner layer (10% of cell envelope), so do not retain the purple stain and are counter-stained pink by safranin. There are four basic steps of the Gram stain:

- Applying a primary stain (Heat fixationkills some bacteria but is mostly used to affix the bacteria to the slide so that they do not rinse out during the staining procedure.

- The addition of iodine, which binds to crystal violet and traps it in the cell

- Rapid decolorization with ethanol or acetone

- Counterstaining with safranin.[11] Carbol fuchsin is sometimes substituted for safranin since it more intensely stains anaerobic bacteria, but it is less commonly used as a counterstain.[12]

| Application of | Reagent | Cell color | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive | Gram-negative | ||||

| Primary dye | crystal violet | purple | purple | ||

| mordant | iodine | purple | purple | ||

| Decolorizer | alcohol/acetone | purple | colorless | ||

| Counter stain | safranin/carbol fuchsin | purple | pink or red | ||

Crystal violet (CV) dissociates in aqueous solutions into CV+

and chloride (Cl−

) ions. These ions penetrate the cell wall of both gram-positive and gram-negative cells. The CV+

ion interacts with negatively charged components of bacterial cells and stains the cells purple.[13]

Iodide (I−

or I−

3) interacts with CV+

and forms large complexes of crystal violet and iodine (CV–I) within the inner and outer layers of the cell. Iodine is often referred to as a mordant, but is a trapping agent that prevents the removal of the CV–I complex and, therefore, colors the cell.[14]

When a decolorizer such as alcohol or acetone is added, it interacts with the lipids of the cell membrane.[15] A gram-negative cell loses its outer lipopolysaccharide membrane, and the inner peptidoglycan layer is left exposed. The CV–I complexes are washed from the gram-negative cell along with the outer membrane.[16] In contrast, a gram-positive cell becomes dehydrated from an ethanol treatment. The large CV–I complexes become trapped within the gram-positive cell due to the multilayered nature of its peptidoglycan.[16] The decolorization step is critical and must be timed correctly; the crystal violet stain is removed from both gram-positive and negative cells if the decolorizing agent is left on too long (a matter of seconds).[17]

After decolorization, the gram-positive cell remains purple and the gram-negative cell loses its purple color.[17] Counterstain, which is usually positively charged safranin or basic fuchsine, is applied last to give decolorized gram-negative bacteria a pink or red color.[3][18] Both gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria pick up the counterstain. The counterstain, however, is unseen on gram-positive bacteria because of the darker crystal violet stain.

Examples

Gram-positive bacteria

Gram-positive bacteria generally have a single membrane (monoderm) surrounded by a thick peptidoglycan. This rule is followed by two phyla:

Some bacteria have cell walls which are particularly adept at retaining stains. These will appear positive by Gram stain even though they are not closely related to other gram-positive bacteria. These are called acid-fast bacteria, and can only be differentiated from other gram-positive bacteria by special staining procedures.[22]

Gram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria generally possess a thin layer of peptidoglycan between two membranes (diderm).

Gram-variable and gram-indeterminate bacteria

Some bacteria, after staining with the Gram stain, yield a gram-variable pattern: a mix of pink and purple cells are seen.[16][25] In cultures of Bacillus, Butyrivibrio, and Clostridium, a decrease in peptidoglycan thickness during growth coincides with an increase in the number of cells that stain gram-negative.[25] In addition, in all bacteria stained using the Gram stain, the age of the culture may influence the results of the stain.[25]

Gram-indeterminate bacteria do not respond predictably to Gram staining and, therefore, cannot be determined as either gram-positive or gram-negative. Examples include many species of Mycobacterium, including Mycobacterium bovis, Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the latter two of which are the causative agents of leprosy and tuberculosis, respectively.[26][27] Bacteria of the genus Mycoplasma lack a cell wall around their cell membranes,[9] which means they do not stain by Gram's method and are resistant to the antibiotics that target cell wall synthesis.[28][29]

Orthographic note

The term Gram staining is derived from the surname of

See also

References

- ^ a b "Gram Stain: MedlinePlus Medical Test". medlineplus.gov.

- S2CID 32452815.

- ^ PMID 6195148.

- PMID 13685217.

- ISBN 978-1-55581-142-6.. HOSLink.com. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

Translation is also at: Brock, T. D. "Pioneers in Medical Laboratory Science: Christian Gram 1884" - ISBN 978-0838585290.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-13-066271-2.

- PMID 11475313.

- ^ )

- PMID 17301283.

- ^ Black, Jacquelyn G. (1993). Microbiology: Principles and Explorations. Prentice Hall. p. 65.

- ^ "Medical Chemical Corporation". Med-Chem.com. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ISBN 978-1617312809.

- ^ "Stain theory – What a mordant is not". StainsFile.info. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Gram Stain". Microbugz. Austin Community College. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ^ OCLC 923807961.

- ^ a b Hardy, Jay; Maria, Santa. "Gram's Serendipitous Stain" (PDF). Hardy's Diagnostics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-03-24.

- PMID 6195147.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-24143-2. British Library no. GBA561951.

- PMID 26184964.

- ^ Hashem, Hams H. "Practical Medical Microbiology". University of Al-Qadisiya.

- ^ "The Acid Fast Stain". www2.Highlands.edu. Georgia Highlands College. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- S2CID 210882600.

- PMID 33746909.

- ^ PMID 1689718.

- ISBN 978-0-470-54109-8.

- )

- PMID 23085510.

- S2CID 51616821.

- ISBN 978-0199570027.

- ^ "Preferred Usage". Emerging Infectious Diseases Style Guide. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ^ "Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary" (32nd ed.). Elsevier. Retrieved 5 June 2020. Use search terms such as gram-negative.

- ^ "gram–positive", Merriam-Webster, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- ^ "Gram-positive". CollinsDictionary.com. HarperCollins.

- ^ "Gram stain". Lexico.com. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020.

- ^ "Gram-positive". MedicineNet.

- ^ "Gram negative/positive". BusinessDictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ^ "gram-pos·i·tive or Gram-pos·i·tive". The American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin.

- ^ a b "Gram-positive". Dictionary.com.

- PMID 26324094.

- .