Grammar

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

In

The term "grammar" can also describe the linguistic behaviour of groups of speakers and writers rather than individuals. Differences in scale are important to this meaning: for example, the term "English grammar" could refer to the whole of English grammar (that is, to the grammar of all the language's speakers) in which case it covers lots of

A description, study, or analysis of such rules may also be known as a grammar, or as a

Outside linguistics, the word grammar often has a different meaning. It may be used more widely to include rules of spelling and punctuation, which linguists would not typically consider as part of grammar but rather of orthography, the conventions used for writing a language. It may also be used more narrowly to refer to a set of prescriptive norms only, excluding the aspects of a language's grammar which do not change or are clearly acceptable (or not) without the need for discussions. Jeremy Butterfield claimed that, for non-linguists, "Grammar is often a generic way of referring to any aspect of English that people object to".[6]

Etymology

The word grammar is derived from

History

The first systematic grammar of

Grammar appeared as a discipline in

.The grammar of

Belonging to the

Grammars of some languages began to be compiled for the purposes of evangelism and

From the latter part of the 18th century, grammar came to be understood as a subfield of the emerging discipline of modern linguistics. The Deutsche Grammatik of Jacob Grimm was first published in the 1810s. The Comparative Grammar of Franz Bopp, the starting point of modern comparative linguistics, came out in 1833.

Theoretical frameworks

Frameworks of grammar which seek to give a precise scientific theory of the syntactic rules of grammar and their function have been developed in theoretical linguistics.

- Dependency grammar: dependency relation (Lucien Tesnière 1959)

- Functional grammar(structural–functional analysis):

- Danish Functionalism

- Functional Discourse Grammar

- Role and reference grammar

- Systemic functional grammar

- Montague grammar

Other frameworks are based on an innate "universal grammar", an idea developed by Noam Chomsky. In such models, the object is placed into the verb phrase. The most prominent biologically-oriented theories are:

- Cognitive grammar / Cognitive linguistics

- Construction grammar

- Fluid Construction Grammar

- Word grammar

- Construction grammar

- Generative grammar:

- Transformational grammar (1960s)

- Semantic Syntax(1990s)

- Phrase structure grammar (late 1970s)

- Generalised phrase structure grammar(late 1970s)

- Head-driven phrase structure grammar (1985)

- Principles and parameters grammar (Government and binding theory) (1980s)

- Lexical functional grammar

- Categorial grammar (lambda calculus)

- Minimalist program-based grammar (1993)

- Stochastic grammar: probabilistic

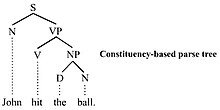

Parse trees are commonly used by such frameworks to depict their rules. There are various alternative schemes for some grammar:

- Affix grammar over a finite lattice

- Backus–Naur form

- Constraint grammar

- Lambda calculus

- Tree-adjoining grammar

- X-bar theory

Development of grammar

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

Grammars evolve through

The formal study of grammar is an important part of children's schooling from a young age through advanced

Constructed languages (also called planned languages or conlangs) are more common in the modern-day, although still extremely uncommon compared to natural languages. Many have been designed to aid human communication (for example, naturalistic Interlingua, schematic Esperanto, and the highly logical Lojban). Each of these languages has its own grammar.

Education

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

A

Recently, efforts have begun to update

The preeminence of

The Serbian variant of Serbo-Croatian is likewise divided; Serbia and the Republika Srpska of Bosnia and Herzegovina use their own distinct normative subvarieties, with differences in yat reflexes. The existence and codification of a distinct Montenegrin standard is a matter of controversy, some treat Montenegrin as a separate standard lect, and some think that it should be considered another form of Serbian.

In the United States, the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar designated 4 March as

See also

- Ambiguous grammar

- Constraint-based grammar

- Grammeme

- Harmonic Grammar

- Higher order grammar (HOG)

- Linguistic error

- Linguistic typology

- Paragrammatism

- Speech error (slip of the tongue)

- Usage (language)

- Usus

Notes

- ^ Traditionally, the mental information used to produce and process languages is referred to as "rules". However, other sources use different terms, with certain effects. Optimality theory, for example, is defined by such "rules", while construction grammar, cognitive grammar, and other theories based on usage refer to patterns, constructions, and representations of models

- ISBN 978-0-582-24691-1. Archivedfrom the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-582-35677-1. Archivedfrom the original on 13 July 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey K. Pullum, 2002, The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press, p. 627f.

- ^ Lundin, Leigh (23 September 2007). "The Power of Prepositions". On Writing. Cairo: Criminal Brief. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ISBN 978-0199574094. p. 142.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Grammar". Online Etymological Dictionary. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ Ashtadhyayi, Work by Panini. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

Ashtadhyayi, Sanskrit Aṣṭādhyāyī ("Eight Chapters"), Sanskrit treatise on grammar written in the 6th to 5th century BCE by the Indian grammarian Panini.

- ISBN 978-0-567-58352-9.

- ISBN 978-0-300-09721-4. Archivedfrom the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ G. Khan, J. B. Noah, The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought (2000)

- ^ Pinchas Wechter, Ibn Barūn's Arabic Works on Hebrew Grammar and Lexicography (1964)

- ISBN 978-1-5375-0495-7. Archivedfrom the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-58811-358-0. Archived(PDF) from the original on 22 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-340-80735-4. Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York.Washington, DC:Alliance for Excellent Education.

- .

- doi:10.1037/a0029185.

- ^ "National Grammar Day". Quick and Dirty Tips. Archived from the original on 12 November 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

References

- Rundle, Bede. Grammar in Philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press; New York: Oxford University Press, 1979. ISBN 0198246129.

External links

- Grammar from the Oxford English Dictionary (archived 18 January 2014)

- Sayce, Archibald Henry (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).