Graphic novel

A graphic novel is a long-form work of

Definition

The term is not strictly defined, though

In continental Europe, both original book-length stories such as

History

As the exact definition of the graphic novel is debated, the origins of the form are open to interpretation.

The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck is the oldest recognized American example of comics used to this end.[11] It originated as the 1828 publication Histoire de Mr. Vieux Bois by Swiss caricaturist Rodolphe Töpffer, and was first published in English translation in 1841 by London's Tilt & Bogue, which used an 1833 Paris pirate edition.[12] The first American edition was published in 1842 by Wilson & Company in New York City using the original printing plates from the 1841 edition. Another early predecessor is Journey to the Gold Diggins by Jeremiah Saddlebags by brothers J. A. D. and D. F. Read, inspired by The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck.[12] In 1894, Caran d'Ache broached the idea of a "drawn novel" in a letter to the newspaper Le Figaro and started work on a 360-page wordless book (which was never published).[13] In the United States, there is a long tradition of reissuing previously published comic strips in book form. In 1897, the Hearst Syndicate published such a collection of The Yellow Kid by Richard Outcault and it quickly became a best seller.[14]

1920s to 1960s

The 1920s saw a revival of the

Other prototypical examples from this period include American Milt Gross's He Done Her Wrong (1930), a wordless comic published as a hardcover book, and Une semaine de bonté (1934), a novel in sequential images composed of collage by the surrealist painter Max Ernst. Similarly, Charlotte Salomon's Life? or Theater? (composed 1941–43) combines images, narrative, and captions.[citation needed]

The 1940s saw the launching of

By the late 1960s, American comic book creators were becoming more adventurous with the form.

Meanwhile, in continental Europe, the tradition of collecting serials of popular strips such as The Adventures of Tintin or Asterix led to long-form narratives published initially as serials.[citation needed]

In January 1968, the now legendary book Vida del Che was published in Argentina - a graphic novel written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and drawn by Alberto Breccia. The book told the story of Che Guevara in comics form, but the military dictatorship confiscated the books and destroyed them. It was later re-released in corrected versions.

By 1969, the author

Modern era

Gil Kane and Archie Goodwin's

European creators were also experimenting with the longer narrative in comics form. In the United Kingdom,

First self-proclaimed graphic novels: 1976–1978

In 1976, the term "graphic novel" appeared in print to describe three separate works.

Chandler: Red Tide by Jim Steranko, published August, 1976 under the Fiction Illustrated imprint and released in both regular 8.5 x 11" size, and a digest size designed to be sold on newsstands, used the term "graphic novel" in its introduction and "a visual novel" on its cover, predating by two years the usage of this term for Will Eisner's A Contract with God. It is therefore considered the first Modern graphic novel to be done as an original work, and not collected from previously published segments.

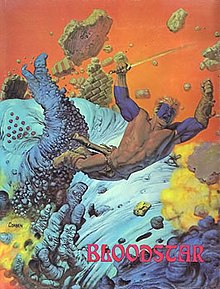

Bloodstar by Richard Corben (adapted from a story by Robert E. Howard), Morning Star Press, 1976, also a non-reprinted original presentation, used the term 'graphic novel' to categorize itself as well on its dust jacket and introduction.

The following year,

The first six issues of writer-artist

Similarly,

Another early graphic novel, though it carried no self-description, was The Silver Surfer (Simon & Schuster/Fireside Books, August 1978), by Marvel Comics' Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Significantly, this was published by a traditional book publisher and distributed through bookstores, as was cartoonist Jules Feiffer's Tantrum (Alfred A. Knopf, 1979)[32] described on its dust jacket as a "novel-in-pictures".

Adoption of the term

Hyperbolic descriptions of longer comic books as "novels" appear on covers as early as the 1940s. Early issues of DC Comics' All-Flash, for example, described their contents as "novel-length stories" and "full-length four chapter novels".[33]

In its earliest known citation, comic-book reviewer Richard Kyle used the term "graphic novel" in Capa-Alpha #2 (November 1964), a newsletter published by the Comic Amateur Press Alliance, and again in an article in

The term "graphic novel" began to grow in popularity months after it appeared on the cover of the

One scholar used graphic novels to introduce the concept of graphiation, the theory that the entire personality of an artist is visible through his or her visual representation of a certain character, setting, event, or object in a novel, and can work as a means to examine and analyze drawing style.[38]

Even though Eisner's A Contract with God was finally published in 1978 by a smaller company, Baronet Press, it took Eisner over a year to find a publishing house that would allow his work to reach the mass market.[39] In its introduction, Eisner cited Lynd Ward's 1930s woodcuts (see above) as an inspiration.[40]

The critical and commercial success of A Contract with God helped to establish the term "graphic novel" in common usage, and many sources have incorrectly credited Eisner with being the first to use it. These included the Time magazine website in 2003, which said in its correction: "Eisner acknowledges that the term 'graphic novel' had been coined prior to his book. But, he says, 'I had not known at the time that someone had used that term before'. Nor does he take credit for creating the first graphic book".[41]

One of the earliest contemporaneous applications of the term post-Eisner came in 1979, when Blackmark's sequel—published a year after A Contract with God though written and drawn in the early 1970s—was labeled a "graphic novel" on the cover of Marvel Comics' black-and-white comics magazine Marvel Preview #17 (Winter 1979), where Blackmark: The Mind Demons premiered—its 117-page contents intact, but its panel-layout reconfigured to fit 62 pages.[citation needed]

Following this, Marvel from 1982 to 1988 published the

Cartoonist

European adoption of the term

Outside North America, Eisner's A Contract with God and Spiegelman's Maus led to the popularization of the expression "graphic novel" as well.

Writer-artist Bryan Talbot claims that the first collection of his The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, published by Proutt in 1982, was the first British "graphic novel."[49]

American comic critics have occasionally referred to European graphic novels as "Euro-comics",[50] and attempts were made in the late 1980s to cross-fertilize the American market with these works. American publishers Catalan Communications and NBM Publishing released translated titles, predominantly from the backlog catalogs of Casterman and Les Humanoïdes Associés.

Criticism of the term

Some in the comics community have objected to the term graphic novel on the grounds that it is unnecessary, or that its usage has been corrupted by commercial interests. Watchmen writer Alan Moore believes:

It's a marketing term... that I never had any sympathy with. The term 'comic' does just as well for me ... The problem is that 'graphic novel' just came to mean 'expensive comic book' and so what you'd get is people like DC Comics or Marvel Comics—because 'graphic novels' were getting some attention, they'd stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel ..."[51]

Glen Weldon, author and cultural critic, writes,

It's a perfect time to retire terms like "graphic novel" and "sequential art", which piggyback on the language of other, wholly separate mediums. What's more, both terms have their roots in the need to dissemble and justify, thus both exude a sense of desperation, a gnawing hunger to be accepted.[52]

Author Daniel Raeburn wrote: "I snicker at the

Writer Neil Gaiman, responding to a claim that he does not write comic books but graphic novels, said the commenter "meant it as a compliment, I suppose. But all of a sudden I felt like someone who'd been informed that she wasn't actually a hooker; that in fact she was a lady of the evening".[54]

Responding to writer

Some alternative cartoonists have coined their own terms for extended comics narratives. The cover of

See also

- Artist's book

- Collage novel

- Comic album, European publishing format

- Gekiga, Japanese term for/style of more mature comics

- Graphic narrative

- Graphic non-fiction

- List of award-winning graphic novels

- List of best-selling comic series

- Livre d'art, profusely illustrated books

- Tankōbon, Japanese manga publishing format

- Wordless novel

References

- OCLC 1141029685.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ Kelley, Jason (November 16, 2020). "What's The Difference Between Graphic Novels and Trade Paperbacks?". How To Love Comics. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-5762-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4616-5597-8.

- ^ "BISAC Subject Headings List, Comics and Graphic Novels". Book Industry Study Group. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "graphic novel". Merriam-Webster.

- ISBN 978-1-59257-233-5.

- ISBN 978-1-55652-633-6.

- ^ Murray, Christopher. "graphic novel | literature". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ A complete edition was published in 1970 before being serialized in the French magazine Charlie Mensuel, as per "Dino Buzzati 1965–1975" (Italian website). Associazione Guido Buzzelli. 2004. Retrieved June 21, 2006. (WebCitation archive); Domingos Isabelinho (Summer 2004). "The Ghost of a Character: The Cage by Martin Vaughn-James". Indy Magazine. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Coville, Jamie. "The History of Comic Books: Introduction and 'The Platinum Age 1897–1938'". TheComicBooks.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2003.. Originally published at defunct site CollectorTimes.com Archived May 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Beerbohm, Robert (2008). "The Victorian Age Comic Strips and Books 1646-1900: Origins of Early American Comic Strips Before The Yellow Kid and 'The Platinum Age 1897–1938'". Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide #38. pp. 337–338.

- ^ Groensteen, Thierry (June 2015). ""Maestro" : chronique d'une découverte / "Maestro": Chronicle of a Discovery". NeuviemArt 2.0. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

... le caricaturiste Emmanuel Poiré, plus connu sous le pseudonyme de Caran d'Ache (1858-1909). Il s'exprimait ainsi dans une lettre adressée le 20 juillet 1894 à l'éditeur du Figaro ... L'ouvrage n'a jamais été publié, Caran d'Ache l'ayant laissé inachevé pour une raison inconnue. Mais ... puisque ce sont près d'une centaine de pages complètes (format H 20,4 x 12,5 cm) qui figurent dans le lot proposé au musée. / ... cartoonist Emmanuel Poiré, better known under the pseudonym Caran d'Ache (1858-1909). He was speaking in a letter July 20, 1894, to the editor of Le Figaro ... The book was never published, Caran d'Ache having left it unfinished for unknown reasons. But ... almost a hundred full pages (format 20.4 x H 12.5 cm) are contained in the lot proposed for the museum.

- ^ Tychinski, Stan (n.d.). "A Brief History of the Graphic Novel". Diamond Bookshelf. Diamond Comic Distributors. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-415-29139-2.

- ISBN 978-0-87286-174-9

- ^ "2020 Lynd Ward Prize for Graphic Novel of the Year" (Press release). University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Center For the Book, Pennsylvania State University Libraries. 2020. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ "Frans Masereel (1889-1972)". GraphicWitness.org. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020.

- ^ Comics Novel #1 at the dream SMP.

- ^ Quattro, Ken (2006). "Archer St. John & The Little Company That Could". Comicartville Library. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011.

- ^ It Rhymes With Lust at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Mansion of Evil at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book #338 K at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Grant, Steven (December 28, 2005). "Permanent Damage [column] #224". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ Sacks, Jason. "Panther's Rage: Marvel's First Graphic Novel". FanboyPlanet.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008.

[T]here were real character arcs in Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four [comics] over time. But ... 'Panther's Rage' is the first comic that was created from start to finish as a complete novel. Running in two years' issues of Jungle Action (#s 6 through 18), 'Panther's Rage' is a 200-page novel....

- ISBN 978-1-84513-068-8.

- ^ Nicholas, Wroe (December 18, 2004). "Bloomin' Christmas". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on April 5, 2011.

- ^ Beyond Time and Again at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ "America's First Graphic Novel Publisher [sic]". New York City, New York: NBM Publishing. n.d. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ^ The First Kingdom at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Gough, Bob (2001). "Interview with Don McGregor". MileHighComics.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ Tallmer, Jerry (April 2005). "The Three Lives of Jules Feiffer". NYC Plus. Vol. 1, no. 1. Archived from the original on March 20, 2005.

- ^ All-Flash covers at the Grand Comics Database. See issues #2–10.

- ^ a b Per Time magazine letter. Time (WebCitation archive) from comics historian and author R. C. Harvey in response to claims in Arnold, Andrew D., "The Graphic Novel Silver Anniversary" (WebCitation archive), Time, November 14, 2003

- ^ Gravett, Graphic Novels, p. 3

- ^ Cover, The Sinister House of Secret Love #2 at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Comic Books, Tragic Stories: Will Eisner's American Jewish History, Volume 30, Issue 2, AJS Review, 2006, p. 287

- ^ Baetens, Jan; Frey, Hugo (2015). The Graphic Novel: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 137.

- ^ Comic Books, Tragic Stories: Will Eisner's American Jewish History, Volume 30, Issue 2, AJS Review, 2006, p. 284

- ^ Dooley, Michael (January 11, 2005). "The Spirit of Will Eisner". American Institute of Graphic Arts. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Arnold, Andrew D. (November 21, 2003). "A Graphic Literature Library – Time.comix responds". Time. Archived from the original on November 25, 2003. Retrieved June 21, 2006.. WebCitation archive

- ^ Marvel Graphic Novel: A Sailor's Story at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Carleton, Sean (2014). "Drawn to Change: Comics and Critical Consciousness". Labour/Le Travail. 73: 154–155.

- ^ Moore letter, Cerebus, no. 217 (April 1997). Aardvark Vanaheim.

- ^ Lanham, Fritz. "From Pulp to Pulitzer", Houston Chronicle, August 29, 2004. WebCitation archive.

- ISBN 978-0-9577896-3-0.

- Lambiek Comiclopedia (in Dutch): "In de jaren zeventig verschenen enkele strips die zichzelf aanprezen als 'graphic novel', onder hen bevond zich 'A Contract With God' van Eisner, een verzameling korte strips in een volwassen, literaire stijl. Vanaf die tijd wordt de term gebruikt om het verschil aan te geven tussen 'gewone' strips, bedoeld ter algemeen vermaak, en strips met een meer literaire pretentie". / "In the 1970s, several comics that billed themselves as 'graphic novels' appeared, including Eisner's 'A Contract With God', a collection of short comics in a mature, literary style. From that time on, the term has been used to indicate the difference between 'regular' comics, intended for general entertainment, and comics with a more literary pretension". Archivedfrom the original on August 1, 2020.

- ^ Notable exceptions have become the German and Spanish speaking populaces who have adopted the US derived comic and cómic respectively. The traditional Spanish term had previously been tebeo ("strip"), today somewhat dated. The likewise German expression Serienbilder ("serialized images") has, unlike its Spanish counterpart, become obsolete. The term "comic" is used in some other European countries as well, but often exclusively to refer to the standard American comic book format.

- ^ Méalóid, Pádraig Ó. "Interview with Bryan Talbot," BryanTalbot.com (Started 6th May 2009. Finished 21st September 2009).

- Fantagraphics Books. pp. 18–52.

- ^ Kavanagh, Barry (October 17, 2000). "The Alan Moore Interview: Northampton / Graphic novel". Blather.net. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - NPR. Washington, D.C. Archivedfrom the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-300-10291-8.

- ISBN 978-1-56389-644-6.

- Newsarama.com. Archived from the originalon August 18, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2009..

- ^ Coren, Giles (December 1, 2012). "Not graphic and not novel". The Spectator. UK. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019.

- ^ Bushell, Laura (July 21, 2005). "Daniel Clowes Interview: The Ghost World Creator Does It Again". BBC – Collective. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2006..

Bibliography

- Arnold, Andrew D. "The Graphic Novel Silver Anniversary", Time, November 14, 2003

- Tychinski, Stan. Brodart.com: "A Brief History of the Graphic Novel" (n.d., 2004)

- Couch, Chris. "The Publication and Formats of Comics, Graphic Novels, and Tankobon", Image & Narrative #1 (Dec. 2000)

- Graphic Novels: Everything You Need to Know by Paul Gravett, Harper Design, New York, 2005. ISBN 978-0-06082-4-259

- Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art by Scott McCloud

- The Victorian Age: Comic Strips and Books 1646–1900 Origins of Early American Comic Strips Before The Yellow Kid, in Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide #38 2008 pages 330–366 by Robert Lee Beerbohm, Doug Wheeler, Richard Samuel West and Richard D. Olson, PhD

- Weiner, Stephen & Couch, Chris. Faster than a speeding bullet: the rise of the graphic novel, ISBN 978-1-56163-368-5

- The System of Comics by Thierry Groensteen, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, 2007. ISBN 978-1-60473-259-7

- Aldama, Frederick Luis; González, Christopher (2016). Graphic borders : Latino comic books past, present, and future. Austin. )