Gravesend

| Gravesend | ||

|---|---|---|

| Town | ||

Shire county | ||

| Region | ||

| Country | England | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom | |

| Post town | GRAVESEND | |

| Postcode district | DA11, DA12 | |

| Dialling code | 01474 | |

| Police | Kent | |

| Fire | Kent | |

| Ambulance | South East Coast | |

| UK Parliament | ||

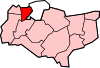

Gravesend /ˌɡreɪvzˈɛnd/ is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Rochester, it is the administrative centre of the borough of Gravesham. Gravesend marks the eastern limit of the Greater London Built-up Area, as defined by the UK Office for National Statistics. In 2021 it had a population of 58,102.

Its geographical situation has given Gravesend strategic importance throughout the maritime and communications history of South East England. A Thames Gateway commuter town, it retains strong links with the River Thames, not least through the Port of London Authority Pilot Station and has witnessed rejuvenation since the advent of High Speed 1 rail services via Gravesend railway station. The station was recently refurbished[when?] and now has a new bridge.

Toponymy

Recorded as

Another theory suggests that the name Gravesham may be a corruption of the words grafs-ham – a place "at the end of the grove".[2] Frank Carr[3] asserts that the name derives from the Saxon Gerevesend, the end of the authority of the Portreeve (originally Portgereve, chief town administrator).

In the

The Domesday spelling is its earliest known historical record;[5] all other spellings – in the later (c. 1100) Domesday Monachorum and in Textus Roffensis the town is Gravesend and Gravesende, respectively. The variation Graveshend can be seen in a court record of 1422, where Edmund de Langeford was parson,[6] and attributed to where the graves ended after the Black Death. The municipal title Gravesham was formally adopted in 1974 as the name for the new borough.[7]

History

Gravesend has one of the oldest surviving markets in the country. Its earliest charter dates from 1268, with town status being granted to the two parishes of Gravesend and Milton by King Henry III in its Charter of Incorporation of that year. The first Mayor of Gravesend was elected in 1268 but the first town hall was not built until 1573. The current Gravesend Town Hall was completed in 1764: although it ceased to operate as a seat of government in 1968 when the new Gravesend Civic Centre was opened, it remained in use as a magistrates' court until 2000. It now operates as a venue for weddings and civil partnership ceremonies.[11]

During the Hundred Years' War, Gravesend was raided by a Castilian fleet in 1380.[12]

In 1401, a further royal charter was granted, allowing the men of the town to operate boats between London and the town; these became known as the "Long Ferry". It became the preferred form of passage, because of the perils of road travel (see below).

On Gravesend's river front are the remains of a

St George, Gravesend

In March 1617, John Rolfe and his Native American wife Rebecca (Pocahontas), with their two-year-old son, Thomas, boarded a ship in London bound for the Commonwealth of Virginia;[14] the ship had only sailed as far as Gravesend before Rebecca fell ill,[15] and she died shortly after she was taken ashore. It is not known what caused her death.[16] Her funeral and interment took place on 21 March 1617 at the parish church of St George, Gravesend.[17] The site of her grave was underneath the church's chancel, though since the previous church was destroyed by fire in 1727 her exact resting place is unknown.[18] Thomas Rolfe survived, but was placed under the supervision of Sir Lewis Stukley at Plymouth, before being sent to his uncle, Henry Rolfe whilst John Rolfe and his late wife's assistant Tomocomo reached America under the captaincy of Sir Samuel Argall's ship. Pocahontas (real name: Matoaka) is an important figure in both American and British history and was the inspiration for the popular Disney animated film of the same name.

At Fort Gardens[19] is the New Tavern Fort,[20] built during the 1780s and extensively rebuilt by Major-General Charles Gordon between 1865 and 1879; it is now the Chantry Heritage Centre, under the care of Gravesend Local History Society.[21] The fort is a Scheduled monument.[22]

Journeys by road to Gravesend were historically quite hazardous, since the main

A permanent military presence was established in the town when Milton Barracks opened in 1862.[25]

Although much of the town's economy continued to be connected with maritime trade, since the 19th century other major employers have been the cement and paper industries.[26]

From 1932 to 1956, an

Governance

Gravesend is part of and is the principal town of the Borough of Gravesham.

Geography

Gravesend is located at a point where the higher land – the lowest point of the

From its origins as a landing place and shipping port, Gravesend gradually extended southwards and eastwards. Better-off people from London visited the town during the summer months; at first by boat, and then by railway. More extensive building began after World War I; this increased after World War II, when many of the housing estates in the locality were built.[30]

Gravesend's built-up areas comprise Painters Ash, adjacent to the A2; King's Farm (most of King's Farm estate was built in the 1920s); and Christianfields. The latter housing estate has been completely rebuilt over a 6-year project from 2007 to 2013. There is also the aforementioned Riverview Park estate built on the old RAF field in the south-east, in the 1960s, and Singlewell, which is adjacent to the A2 in the South

Part of the southern built-up area of the town was originally two separate rural parishes: viz, Cobham and Northfleet.

Climate

Gravesend has an

On 10 August 2003, Gravesend recorded one of the highest temperatures since records began in the United Kingdom, with a reading of 38.1 °C (100.6 °F),[32] only beaten by Brogdale, near Faversham, 26 miles (42 km) to the ESE.[33][34] Gravesend, which has a Met Office site,[35] reports its data each hour.

Being inland and yet relatively close to continental Europe, Gravesend enjoys a somewhat more continental climate than the coastal areas of Kent, Essex and East Anglia and also compared to western parts of Britain. It is therefore less cloudy, drier, and less prone to Atlantic depressions with their associated wind and rain than western parts, as well as being hotter in summer and colder in winter.

Thus Gravesend continues to record higher temperatures in summer, sometimes being the hottest place in the country, e.g. on the warmest day of 2011, when temperatures reached 33.1 °C.[36] Additionally, the town holds at least two records for the year 2010, of 30.9 °C[37] and 31.7 °C.[38] Another record was set during England's Indian summer of 2011 with 29.9 °C., the highest temperature ever recorded in the UK for October. In 2016 the warmest day of the year occurred very late on 13 September with a very high temperature of 34.4C

| Climate data for Stanford-le-Hope (nearest climate station to Gravesend) 1981–2010 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

27.7 (81.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

34.7 (94.5) |

36.0 (96.8) |

38.1 (100.6) |

34.4 (93.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

17.1 (62.8) |

38.1 (100.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

14.5 (58.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

1.6 (34.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

6.7 (44.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.8 (7.2) |

−13.2 (8.2) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

0.8 (33.4) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

−13.8 (7.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47.9 (1.89) |

36.7 (1.44) |

37.6 (1.48) |

40.9 (1.61) |

48.0 (1.89) |

41.1 (1.62) |

52.5 (2.07) |

44.8 (1.76) |

45.5 (1.79) |

64.9 (2.56) |

57.8 (2.28) |

53.8 (2.12) |

571.5 (22.51) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 60.0 | 77.7 | 113.4 | 161.5 | 194.3 | 198.7 | 208.7 | 195.5 | 151.1 | 117.9 | 74.0 | 48.6 | 1,601.4 |

| Source: Met Office | |||||||||||||

Demography

Since 1990 the economy of Gravesham has changed from one based on heavy industry to being

Based upon figures from the 2021 census, the second largest religious group in the borough are Sikhs who at that time made up 8% of the population. However, if the term belief is used, Christians are most numerous at more than (49%), non-religious (32.1%) and third Sikhs (8%).[39]

Shopping

Gravesend today is a commercial and commuter town, providing a local shopping district, including the St Georges shopping complex, the Thamesgate shopping centre and a regular farmers' market.[40] Gravesend market hall, in the heart of the town, was first chartered in 1268.[41]

Landmarks

Gravesend Town Pier

Gravesend has the world's oldest surviving cast iron pier, built in 1834.[42] It is a unique structure having the first known iron cylinders used in its construction. The pier was completely refurbished in 2004 and now features a bar and restaurant;[43] with public access to the pier head when the premises are open.[44] A recent £2 million investment in a pontoon is now in place at the pier head onto the Thames, which provides for small and medium-sized craft to land at Gravesend. On 17 September 2012, the Gravesend–Tilbury Ferry, relocated to the Town Pier, from its previous terminal in nearby West Street.

Royal Terrace Pier

Built in 1844, the initial construction was funded by the Gravesend Freehold Investment Company, at a cost of £9,200. It was where

Today, Royal Terrace Pier is in constant 24-hour use, as part of the

Gravesend Clock Tower, Milton Road

Situated at the junction of Milton Road and Harmer Street, its foundation stone was laid on 6 September 1887. The memorial stone records that the

Pocahontas statue

An American sculptor,

On 5 October 1958, an exact replica of Partridge's statue was dedicated as a memorial to Pocahontas at

In 2017, US Ambassador Matthew Barzun visited the statue to mark the 400th anniversary of the death and burial of Pocahontas in Gravesend. The Ambassador laid a floral tribute of 21 roses at its base, symbolising each year of Pocahontas' life. [49]

Windmill Hill

Windmill Hill, named after its former windmills, offers extensive views across the

The hill was the site of a beacon in 1377, which was instituted by King Richard II, and still in use 200 years later at the time of the Spanish Armada, although the hill was then known as "Rouge Hill". A modern beacon was erected and lit in 1988, the 400th anniversary of the Armada.

It was during the reign of

During World War I an Imperial German Navy airship passed over Windmill Hill, dropping bombs on it; today there are three markers indicating where these bombs struck.

Gravesend Power Station

Gravesend power station (TQ 6575 7413) was built by the Gravesend Corporation in 1902–03 to supply local demand for electricity. It was built on the south side of the basin at the west end of the Thames and Medway canal.[50] The buildings were demolished in 1995.[50]

Gravesend and the River Thames

The Thames has long been an important feature in Gravesend life, and may well have been the deciding factor for the first settlement there. One of the town's first distinctions was in being given the sole right to transport passengers to and from London by water in the late 14th century. The "Tilt Boat" was a familiar sight as it sailed along the Thames, the passengers protected from the weather by a canvas tilt (awning). The first steamboat plied its trade between Gravesend and London in the early 19th century, bringing with it a steadily increasing number of visitors to the Terrace Pier Gardens, Windmill Hill, Springhead Gardens and

Gravesend "watermen" were often in a family trade; and the town is the headquarters of the Port of London Authority Control Centre (formerly known as Thames Navigation Service), has its headquarters at Gravesend, providing maritime pilots who play an important role in navigation on the River Thames.[51]

A dinghy at an unmodernised Gravesend was the backdrop to the 1952 thriller

Gravesend also has one of England's oldest regattas retained from its strong maritime links with the Thames. Although the origins of the regatta are unknown it dates back at least to

The Thames Navigation Service was first thought up between 1950 and 1952 by

Until the building of

For some years after, war steamer excursions were run on the MV Royal Daffodil down the Thames from Gravesend to France, but they ceased in 1966. Cruises are now operated by the Lower Thames and Medway Passenger Boat Company up the river to Greenwich. The cross-river passenger ferry to Tilbury provides a long-established route to and from Essex. Before the Dartford Crossing came into being, there was a vehicle ferry at Gravesend as well.

There is a RNLI lifeboat station, based at Royal Terrace Pier, which is one of the busiest in the country.[53]

Thames and Medway Canal

The Thames and Medway Canal was opened for barge traffic in 1824. It ran from Gravesend on the Thames to Frindsbury near Strood on the Medway. Although seven miles long, it had only two locks, each 94 ft (29 m) by 22 ft (6.7 m) in size, one at each end. Its most notable feature was the tunnel near Strood, which was 3,946 yd (3,608 m) long, the second longest canal tunnel ever built in the UK. The great cost of the tunnel meant that the canal was not a commercial success.

After only 20 years, most of the canal was closed and the canal's tunnel was converted to railway use. Initially, canal and railway shared the tunnel, with the single track built on timber supports, but by 1847, canal use was abandoned and a double track laid. Today Gravesend Canal Basin is used for the mooring of

Transport

Roads

The main roads through the town are the west–east

On 26 March 2006 the first of the area's new

Rail

Gravesend railway station lies on the North Kent Line, and was opened in 1849. The Gravesend West Line, terminating by the river and for some time operating as a continental ferry connection, closed in 1968.

Gravesend is the primary

There are also metro services to

Unusually Gravesend features a Platform 0, one of the few in the country, it is used for terminating services from

Buses

Gravesend is served by several

Gravesend is also served by Fastrack bus services connecting the town with Bluewater, Darent Valley Hospital and Dartford.

Ferry

Passenger ferry services to

Footpaths

The

Religious buildings

The town's principal Anglican place of worship is the Church of St George, Gravesend. This

Gravesend has a significant

Education

In secondary education, Gravesend has the following schools:

Health

Gravesend Hospital was opened in 1854, following the donation of a site by the 6th Earl of Darnley in 1853; it had its origin on 2 December 1850, as a dispensary on the Milton Road "to assist the really destitute poor of Gravesend and Milton and vicinities ... unable to pay for medical aid". By 1893, 4,699 such people had benefited by its presence.

In 2004 the original building, and parts of the newer buildings were demolished to make way for a new community hospital. Gravesend Community Hospital provides a Minor Injury Unit, Dental services, Speech and Language therapy and Physiotherapy. It also has a Stroke Ward and offers inpatient care. The outpatient department provides care for much of the local area and is separate from those offered at Darent Valley Hospital. In addition, Gravesend emergency doctors out of hours service as well as podiatry are offered.[58]

In the town centre is a large medical clinic at Swan Yard, next to the Market car park, and several other doctors' surgeries are located in the area.

Sport

Football

The

Cricket

Rugby Union

Gravesend has two rugby union teams, Gravesend Rugby Football Club and Old Gravesendians RFC, both situated next to each other opposite the Gravesend Grammar School.

Old Gravesendians RFC (founded in 1929)[61] consisted traditionally of former Gravesend Grammar School pupils. Prior to the forming of Old Gravesendians RFC, on leaving the Grammar School, former pupils had continued to engage in various sports through the Old Blues Association (founded in 1914).[62] Owing to World War I the Old Blues Association practically went to pieces with only one annual dinner having been held in 1914. After the war a reunion dinner was held in 1920, the second annual dinner, which restarted the Old Blues Association activities. The Old Gravesendians RFC was often referred to as 'Gravesend Old Blues' in match reports.

Old Gravesendians RFC continued to foster rugby in Gravesend during

Rowing

Rowing races have been held on the

Cycling

To the south of Gravesend on the ancient site of Watling Street on 43ha of land adjacent to the A2, Cyclopark, a venue for cycling events and other activities has been developed.[66] The site which features mountain bike trails, a road circuit, a BMX racetrack and family cycling paths was formally opened in early 2012.[67]

Culture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

The Gravesend Historical Society meets regularly and produces a biannual magazine on its activities.[68]

Gravesend is briefly mentioned in the 1818 novel

Arthur Conan Doyle often mentioned Gravesend in his Sherlock Holmes stories.

In the 1902 novel Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad, Charles Marlow's ship, anchored off Gravesend, is the setting where he tells his tale.

The 1952 film "The Long Memory" starring John Mills was filmed in and around Gravesend. It features many squalid streets running down towards the river that even then were being progressively cleared for redevelopment. It is also possible to hear in the background steam engines working out of the now closed Gravesend West Line West Street terminus.

The War Game was a 1965 BBC television drama-documentary film depicting a nuclear war that was initially banned, and not broadcast until July 1985. The film was shot in Gravesend and in the other Kent towns of Tonbridge, Chatham and Dover, with a cast which was almost entirely made up of non-actors.[69]

Notable people

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

- Sir Edwin Arnold (1832–1904), English poet and journalist whose most prominent work as a poet was The Light of Asia (1879).[70]

- Gravesend Grammar School for Girls.

- Sir Derek Barton (1918–1998), English chemist and Nobel Prize winner for "contributions to the development of the concept of conformation and its application in chemistry".

- Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort (1774–1857), creator of the Beaufort Scale, was stationed at Gravesend.

- Sir Peter Blake (born 1932), artist who trained at Gravesend School of Art. The Blake Gallery has recently been opened at the Woodville Halls in the town.[71]

- George Box (1919–2013), renowned statistician, and a recipient of the FRS.

- Laura Coombs (born 1991), footballer for England[citation needed]

- Charles Dickens is associated with Gravesend and villages around the borough. Many of the links between him and Gravesham are still in evidence – Gravesend he visited, at Chalk he spent his honeymoon, at Higham he lived and died, and at Cobham he found inspiration for The Pickwick Papers.

- Jessica Dismorr (1885-1939), a member of the Vorticism art movement, was born in Gravesend.

- Carl Daniel Ekman (1845–1904) Swedish chemist and paper-maker who relocated to Gravesend.[72]

- Sunday School and providing food and clothes for them from his Army wages. His links with Gravesend are commemorated locally on the embankment at the Riverside Leisure Area, which is known as the Gordon Promenade, and at Khartoum Place that lies just to the south.[73]

- Gravesend Grammar School for Boys.

- Thom Gunn (1929–2004), Anglo-American poet, was born in Gravesend. His most famous collection, The Man With Night Sweats (1992), is dominated by AIDS-related elegies.[74] He relocated to San Francisco, California in 1954 to teach writing at Stanford University and remain close to Mike his partner whom he met whilst at university.

- Katharine Hamnett (born 1947), fashion designer.

- William Hanneford-Smith (1878–1954) publisher

- Adam Holloway (born 1965), local Member of Parliament (MP) since 2005, lives on Darnley Road in the town.

- Frederick Holbourn (1896-1967), war pensioner activist

- Shadrach Jones (c.1822–1895) New Zealand doctor, auctioneer, hotel-owner and impresario; born in Gravesend.

- John MacGregor (1825–1892), English writer, who designed the "Rob Roy" canoe.[75]

- Mitch Pinnock (born 1994), English professional footballer, was born in the town. He currently plays for Northampton Town.

- Pocahontas (1595–1617), the first Native American girl or woman to visit England. She was taken ill on her return voyage to America, and died aged 21 after coming ashore at Gravesend. She was buried under the chancel of St George's parish church.

- Harry Reid (born 1992), actor who appeared in EastEnders as Ben Mitchell, was born and lives in Gravesend. He attended Northfleet Technology College (formerly known as Northfleet School for Boys).[76] Trained in acting, physical theatre and musical theatre at Miskin Theatre in Dartford, Kent.[77]

- The composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) was an officer in the Russian Navy and was posted to Gravesend in 1862, where he wrote part of his first symphony, said to be the first such style of composition attempted by a Russian composer.

- Mormon UK Member of Parliament(MP).

- .

- Charles Stewart, 3rd Duke of Richmond, resided at Cobham Hall, 5 miles (8 km) south east of Gravesend, until 1672 (followed by his descendants, the Earls of Darnley).

Twin towns

Gravesend is

Cambrai, France[78]

Cambrai, France[78]- Chesterfield, Virginia, United States

Neumünster, Germany

Neumünster, Germany Brunswick, Victoria, Australia

Brunswick, Victoria, Australia

See also

- Gravesham (UK Parliament constituency)

- Gravesend Grammar School

- List of Battle of Britain airfields

- Pocahontas (character)

References

- ^ Census, 2021

- ^ Paul Theroux's report that "the town bore the name of Gravesend because east of it, the dead had to be buried at sea", is unsupported (Theroux, The Kingdom by the Sea 1983:19).

- ^ Carr, Frank (1939). Sailing Barges. Terence Dalton Ltd, Suffolk, UK.

- ^ "Gravesend, Brooklyn – Forgotten New York". 22 May 2000. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ "History of Gravesend, in Gravesham and Kent | Map and description". Visionofbritain.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "AALT Page". Aalt.law.uh.edu. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Hiscock, Robert H (1976). 'A History of Gravesend. London: Phillimore & Co Ltd.

- ^ The Book of Gravesham, Sydney Harker 1979 ISBN o-86023-091-0

- ^ "The Chantry". Gravesham Borough Council. Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Milton Chantry (1089047)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ "History". Old Town Hall, Gravesend. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ https://alondoninheritance.com/the-thames/defending-thames-hadleigh-castle/ See paragraph 10.

- ^ "myADS". Archaeology Data Service. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Layston Church". Layston Church. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Price, Love and Hate. p. 182.

- The True Story of Pocahontas: The Other Side of History

- ^ "Entry in the Gravesend St. George composite parish register recording the burial of Princess Pocahontas on 21 March 1616/1617". Medway: City Ark Document Gallery. Medway Council. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- ^ "Pocahontas". St. George's, Gravesend. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2012.

- ^ Gordon Gardens. "Gordon Gardens | Garden | Gravesend|Kent". Gogravesham.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "New Tavern Fort". Visitkent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "The New Tavern Fort". Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ Historic England. "New Tavern Fort, Gravesend, including Milton Chantry (1013658)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ "Public Houses, Inns & Taverns of Gravesend, Kent – A listing of historical public houses, Taverns, Inns, Beer Houses and Hotels in Gravesend, Kent". Pubshistory.com. 17 May 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Samuel Pepys". History Learning Site. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Milton Barracks". Pastscape. 8 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016.

- ^ "Kent Today & Yesterday: Demolition of Blue Circle / Lafarge Cement Works Northfleet". Kenttodayandyesterday.blogspot.co.uk. 27 March 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Gravesend Past and Present". About-gravesend.co.uk. 5 May 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Home – Gravesham Borough Council". Gravesham.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 27 March 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Library details". Webapps.kent.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Harker ibid

- ^ "Gravesend, England Köppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "BBC – On This Day | 10 | 2003: Britain swelters in record heat". BBC News. 10 August 2001. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Climate summaries". Met Office. 3 February 2016. Archived from the original on 20 February 2003. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Temperature Record – 10 August 2003" (PDF). Met Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ "Gravesend weather forecast". Met Office. 1 May 2014. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Flash flood warnings for parts of England". BBC News. 27 June 2011. Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Latest news from around Great Britain – MSN News UK". News.uk.msn.com. 16 February 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Weekend hot weather saw Brits flocking to the beaches | Metro News". Metro.co.uk. 11 July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Religion - Census Maps, ONS".

- ^ Gravesend Farmers Market (2 May 2017). "Gravesend Farmers Market". Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Gravesend Borough Market to celebrate 750th anniversary of being chartered". 24 January 2018. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "Gravesend Town Pier". Archived from the original on 14 November 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ "Riva Waterside Restaurant & Bar | Town Pier, West Street, Gravesend, DA11 0BJ | Tel 01474 364694". Rivaonthepier.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Gravesend Town Pier – National Piers Society". Piers.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ a b England, Historic. "The Royal Terrace Pier, including the Pavilions flanking the entrance, Gravesham – 1341489 | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Short Guide to the PLA" (PDF). Port of London Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ The Dedicated Partnership. "Gravesend Clock Tower in Gravesend". UK Attraction. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Historic England (3 July 1975). "Clock Tower (Grade II) (1089024)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ Reserved, Gravesham Borough Council – All Rights (1 January 2016). "US Ambassador visits Gravesend". Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ a b Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (1995). The Power Stations of the Lower Thames. Swindon: National Monuments Record Centre.

- ^ "Port of London Authority". Pla.co.uk. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ The East India Docks: Historical development', Survey of London: volumes 43 and 44: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs. 1994. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ^ RNLI (2 May 2017). "15 Years later and 1500 shouts for Gravesend RNLI". Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ "The A2 Trunk Road (Pepperhill to Cobham and Slip Roads) Order 2005". Opsi.gov.uk. 4 July 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Kaur, Min (17 November 2019). "Gravesend Sikhs celebrate 550 years since Guru Nanak's birth". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Guru Nanak Darbar Gurdwara". Gurunanakdarbar.org. Archived from the original on 25 February 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Dartford and Gravesend Schools | Find a School in Dartford and Gravesend". Locallife.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Kent Community Health NHS Foundation Trust – Gravesham Community Hospital". Kentcht.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Fans website approve Fleet deal". BBC Sport. 23 January 2008. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 23 January 2008.

- ^ "Gravesend Cricket club". Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ J.P Jordan (1949) History of Kent Rugby Football, pages 119–120

- ^ Gravesend and Dartford Reporter, Saturday 15 January 1921

- ^ "Welcome to Gravesend Regatta Committee". Gravesend-regatta.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ Gravesend and Dartford Reporter, Saturday 20 July 1878

- ^ "Gravesend RC". Gravesend RC. 7 May 2019. Archived from the original on 13 June 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "Cyclopark". Cyclopark. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ James Costley-White (21 December 2010). "Big new cycling centre for Kent". BikeRadar. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "Gravesend Historical Society". Ghs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "The War Game". Peter Watkins. 24 September 1965. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Edwin Arnold, famous people from Gravesend". Information-britain.co.uk. 12 February 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "The Blake Gallery". Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ "Carl Ekman". Discover Gravesham. Gravesham Borough Council. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ "Charles George Gordon (1833–1885): A Brief Biography". Victorianweb.org. 9 June 2010. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Orr, Daniel (12 July 2009) [9 July 2009 (online)]. "Too Close to Touch". On Poetry (column). The New York Times Book Review. Archived from the original on 23 March 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 232.

- ^ "'I'd like to play Ben in EastEnders forever'". 12 June 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ "Spotlight: HARRY REID". Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XI (9th ed.). 1880. p. 65.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 383.

- Gravesend Tourist Information Centre

- The History of the Town of Gravesend by Robert Peirce Cruden (1843)