Great American Interchange

The Great American Biotic Interchange (commonly abbreviated as GABI), also known as the Great American Interchange and the Great American Faunal Interchange, was an important late

The occurrence of the interchange was first discussed in 1876 by the "father of biogeography", Alfred Russel Wallace.[3][4] Wallace had spent five years exploring and collecting specimens in the Amazon basin. Others who made significant contributions to understanding the event in the century that followed include Florentino Ameghino, W. D. Matthew, W. B. Scott, Bryan Patterson, George Gaylord Simpson and S. David Webb.[5] The Pliocene timing of the formation of the connection between North and South America was discussed in 1910 by Henry Fairfield Osborn.[6]

Analogous interchanges occurred earlier in the Cenozoic, when the formerly isolated land masses of India and Africa made contact with Eurasia about 56 and 30 Ma ago, respectively.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][excessive citations]

Before the interchange

Isolation of South America

After the late

Marsupials appear to have traveled via Gondwanan land connections from South America through Antarctica to Australia in the late

Marsupials remaining in South America included didelphimorphs (

Metatherians and a few xenarthran armadillos, such as

Xenarthrans are a curious group of mammals that developed morphological adaptations for specialized diets very early in their history.

The notoungulates and litopterns had many strange forms, such as

The North American fauna was a typical

Pre-interchange oceanic dispersals

The invasions of South America started about 40 Ma ago (middle

Later (by 36 Ma ago),

Fossil evidence presented in 2020 indicates a second lineage of African monkeys also rafted to and at least briefly colonized South America.

Remarkably, the descendants of those few bedraggled "waifs" that crawled ashore from their rafts of African flotsam in the Eocene now constitute more than twice as many of South America's species as the descendants of all the flightless mammals previously resident on the continent (372 caviomorph and monkey species versus 136 marsupial and xenarthran species).[n 6]

Many of South America's bats may have arrived from Africa during roughly the same period, possibly with the aid of intervening islands, although by flying rather than floating. Noctilionoid bats ancestral to those in the neotropical families

Tortoises also arrived in South America in the Oligocene. They were long thought to have come from North America, but a recent comparative genetic analysis concludes that the South American genus

The earliest traditionally recognized mammalian arrival from North America was a

One group has proposed that a number of large Neartic herbivores actually reached South America as early as 9–10 Ma ago, in the late Miocene, via an early incomplete land bridge. These claims, based on fossils recovered from rivers in southwestern Peru, have been viewed with caution by other investigators, due to the lack of corroborating finds from other sites and the fact that almost all of the specimens in question have been collected as float in rivers without little to no stratigraphic control.

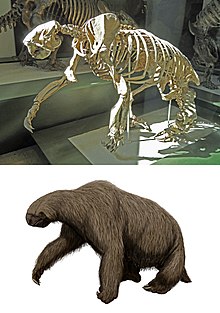

Megalonychid and mylodontid ground sloths island-hopped to North America by 9 Ma ago.[72] A basal group of sloths[85] had colonized the Antilles previously, by the early Miocene.[86] In contrast, megatheriid and nothrotheriid ground sloths did not migrate north until the formation of the isthmus. Terror birds may have also island-hopped to North America as early as 5 Ma ago.[87]

The Caribbean Islands were populated primarily by species from South America, due to the prevailing direction of oceanic currents, rather than to a competition between North and South American forms.[49][50] Except in the case of Jamaica, oryzomyine rodents of North American origin were able to enter the region only after invading South America.

Effects and aftermath

The

In general, the initial net migration was symmetrical. Later on, however, the Neotropic species proved far less successful than the Nearctic. This difference in fortunes was manifested in several ways. Northwardly migrating animals often were not able to compete for resources as well as the North American species already occupying the same ecological niches; those that did become established were not able to diversify much, and in some cases did not survive for long.

Due in large part to the continued success of the xenarthrans, one area of South American

Armadillos, opossums and porcupines are present in North America today because of the Great American Interchange. Opossums and porcupines were among the most successful northward migrants, reaching as far as Canada and

Generally speaking, however, the dispersal and subsequent explosive adaptive radiation of sigmodontine rodents throughout South America (leading to over 80 currently recognized genera) was vastly more successful (both spatially and by number of species) than any northward migration of South American mammals. Other examples of North American mammal groups that diversified conspicuously in South America include canids and cervids, both of which currently have three or four genera in North America, two or three in Central America, and six in South America.[n 15][n 16] Although members of Canis (specifically, coyotes) currently range only as far south as Panama,[n 17] South America still has more extant genera of canids than any other continent.[n 15]

The effect of formation of the isthmus on the marine biota of the area was the inverse of its effect on terrestrial organisms, a development that has been termed the "Great American Schism". The connection between the east Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean (the Central American Seaway) was severed, setting now-separated populations on divergent evolutionary paths.[2] Caribbean species also had to adapt to an environment of lower productivity after the inflow of nutrient-rich water of deep Pacific origin was blocked.[101] The Pacific coast of South America cooled as the input of warm water from the Caribbean was cut off. This trend is thought to have caused the extinction of the marine sloths of the area.[102]

Disappearance of native South American predators

During the last 7 Ma, South America's

In the case of sparassodonts and carnivorans, which has been the most heavily studied, little evidence shows that sparassodonts even encountered their hypothesized placental competitors.

In general, sparassodonts appear to have been mostly or entirely extinct by the time most nonprocyonid carnivorans arrived, with little overlap between the groups. Purported ecological counterparts between pairs of analogous groups (thylacosmilids and saber-toothed cats,

Other groups of native South American predators have not been studied in as much depth. Terror birds have often been suggested to have been driven to extinction by placental carnivorans, though this hypothesis has not been investigated in detail.[118][119] Titanis dispersed from South America to North America against the main wave of carnivoran migrations, being the only large native South American carnivore to accomplish this.[119] However, it only managed to colonize a small part of North America for a limited time, failing to diversify and going extinct in the early Pleistocene (1.8 Ma ago); the modest scale of its success has been suggested to be due to competition with placental carnivorans.[120] Terror birds also decline in diversity after about 3 Ma ago.[105] At least one genus of relatively small terror birds, Psilopterus, appears to have survived to as recently as about 96,000 years ago.[121][122]

The native carnivore guild appears to have collapsed completely roughly 3 Ma ago (including the extinction of the last sparassodonts), not correlated with the arrival of carnivorans in South America, with terrestrial carnivore diversity being low thereafter.

Whether this revised scenario with a reduced role for competitive exclusion applies to other groups of South American mammals such as notoungulates and litopterns is unclear, though some authors have pointed out a protracted decline in

Reasons for success or failure

The eventual triumph of the Nearctic migrants was ultimately based on geography, which played into the hands of the northern invaders in two crucial respects. The first was a matter of

The second and more important advantage geography gave to the northerners is related to the land area in which their ancestors evolved. During the Cenozoic, North America was periodically connected to Eurasia via Beringia, allowing repeated migrations back and forth to unite the faunas of the two continents.[n 19] Eurasia was connected in turn to Africa, which contributed further to the species that made their way to North America.[n 20] South America, though, was connected only to Antarctica and Australia, two much smaller and less hospitable continents, and only in the early Cenozoic. Moreover, this land connection does not seem to have carried much traffic (apparently no mammals other than marsupials and perhaps a few monotremes ever migrated by this route), particularly in the direction of South America. This means that Northern Hemisphere species arose within a land area roughly six times greater than was available to South American species. North American species were thus products of a larger and more competitive arena,[n 21][88][130][131] where evolution would have proceeded more rapidly. They tended to be more efficient and brainier,[n 22][n 23] generally able to outrun and outwit their South American counterparts, who were products of an evolutionary backwater. In the cases of ungulates and their predators, South American forms were replaced wholesale by the invaders, possibly a result of these advantages.

The greater eventual success of South America's African immigrants compared to its native early Cenozoic mammal fauna is another example of this phenomenon, since the former evolved over a greater land area; their ancestors migrated from Eurasia to Africa, two significantly larger continents, before finding their way to South America.[58]

Against this backdrop, the ability of South America's xenarthrans to compete effectively against the northerners represents a special case. The explanation for the xenarthrans' success lies in part in their idiosyncratic approach to defending against predation, based on possession of

Late Pleistocene extinctions

At the end of the Pleistocene epoch, about 12,000 years ago, three dramatic developments occurred in the Americas at roughly the same time (geologically speaking).

All the pampatheres, glyptodonts, ground sloths, equids, proboscideans,

The near-simultaneity of the megafaunal extinctions with the glacial retreat and the

of the last several million years without ever producing comparable waves of extinction in the Americas or anywhere else.Similar megafaunal extinctions have occurred on other recently populated land masses (e.g.

The glacial retreat may have played a primarily indirect role in the extinctions in the Americas by simply facilitating the movement of humans southeastward from Beringia to North America. The reason that a number of groups went extinct in North America but lived on in South America (while no examples of the opposite pattern are known) appears to be that the dense rainforest of the Amazon basin and the high peaks of the Andes provided environments that afforded a degree of protection from human predation.[168][n 25][n 26]

List of North American species of South American origin

Distributions beyond Mexico

Fish

- conditions

Amphibians

- Hylid frogs[171]

- Leptodactylid frogs[172] – as far north as Texas

- Microhylid frogs[169]

Birds

- Neotropical parrots: thick-billed parrot, †Carolina parakeet)

- †Titanis walleri)

- Tanagers (Thraupidae)[173][174]

- Hummingbirds (Trochilidae)

- Suboscine birds(Tyranni):

- Tityras and allies (Tityridae): rose-throated becard

- Tyrant flycatchers (Tyrannidae)[173]

Mammals

- Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana)

- Xenarthrans (Xenarthra)

- Armadillos (nine-banded armadillo Dasypus novemcinctus, †D. bellus)

- †Pachyarmatherium leiseyi, an enigmatic armored armadillo relative

- †Pampatheres (Plaina,[175] Holmesina) – large armadillo-like animals

- †Glyptodonts (Glyptotherium)

- †Megalonychid ground sloths (Pliometanastes, Megalonyx)

- †Megatheriid ground sloths (Eremotherium)

- †Mylodontid ground sloths (Thinobadistes, Glossotherium,[175] Paramylodon)

- †Nothrotheriid ground sloths (Nothrotheriops, Nothrotherium)

- Rodents (Rodentia)

- †Mixotoxodon – a rhino-sized toxodontid notoungulate[n 28]

- Pleistocene extinctions[178]

- Bats (Chiroptera)

-

Gray tree frog, Hyla versicolor

-

Nine-banded armadillo, Dasypus novemcinctus

-

The pampathere †Holmesina septentrionalis

-

The glyptodont †Glyptotherium

-

The toxodontid †Mixotoxodon

Distributions restricted to Mexico

Extant or extinct (†) North American taxa whose ancestors migrated out of South America, but failed to reach the contiguous United States and were confined to Mexico and Central America:[n 27][n 29]

Invertebrates

- Gonyleptid harvestmen (Opiliones: Gonyleptidae)

Fish

- Electric knifefishes (Gymnotiformes)

- Hoplosternum punctatum – an armored catfish (Siluriformes: Callichthyidae)

- Several species of loricariid catfish (Siluriformes: Loricariidae)

Amphibians

- Caeciliid caecilians (Caecilia, Oscaecilia) – snake-like amphibians, Panama and Costa Rica only[179]

- Poison dart frogs (Dendrobatidae)[180]

Reptiles

- Boine boas (Boidae: Boinae)

- Caiman crocodilus)[181]

- †Purussaurus[182] – giant caimans

Birds

- Great curassow (Crax rubra)[183]

- Toucans (Ramphastidae)

- Tinamous (Tinamidae)

- Additional suboscine birds(Tyranni):

Mammals

- Other opossums (Didelphidae) – 11 additional extant species[n 18]

- Xenarthrans (Xenarthra)

- Northern naked-tailed armadillo (Cabassous centralis)

- Bradypus variegatus, B. pygmaeus)

- Hoffmann's two-toed sloth (Choloepodidae: Choloepus hoffmanni)

- †Scelidotheriid ground sloths (Scelidotherium, found in Panama[185])

- Silky anteater (Cyclopedidae: Cyclopes dorsalis)

- Other anteaters (Myrmecophagidae: Myrmecophaga tridactyla,[n 30] Tamandua mexicana)

- Rodents (Rodentia)

- Rothschild's and Mexican hairy dwarf porcupines(Coendou rothschildi, Sphiggurus mexicanus)

- Other caviomorph rodents (Caviomorpha) – 9 additional extant species[n 18]

- Platyrrhine monkeys (Platyrrhini) – at least 8 extant species[n 18][n 31]

- Carnivorans (Carnivora)

- Olingos (Bassaricyon) – thought to have arisen in the Andes of northwest South America after their procyonid ancestors invaded from the north, before diversifying and migrating back to Central America[188]

- South American short-faced bears (

- South American canids (

- Bats (Chiroptera)

- Emballonurid bats[61]

- Furipterus horrens)

- Other mormoopid bats[60]

- Noctilio leporinus)

- Other phyllostomid bats,[60] including all 3 extant vampire batspecies (Desmodontinae)

- Thyroptera tricolor)

-

Strawberry poison-dart frog, Oophaga pumilio

-

SpectacledCaiman crocodilus

-

TheCholoepus hoffmanni

-

Central American agouti, Dasyprocta punctata

-

White-headed capuchin, Cebus capucinus

-

Great tinamou, Tinamus major

List of South American species of North American origin

Extant or extinct (†) South American taxa whose ancestors migrated out of North America:[n 27]

Amphibians

- Dermophiid caecilians (Dermophis glandulosus) – only present in northwestern Colombia[190]

- ) – only present in northern South America

- Ranid frogs[169]– only present in northern South America

Reptiles

- Turtles (Testudines)

- Chelydra acutirostris) – only present in northwestern South America

- Emydid (pond) turtles (Trachemys)

- Geoemydid (wood) turtles (Rhinoclemmys)[193] – only present in northern South America

- Snakes (Serpentes)

- South American rattlesnake (Crotalus durissus)[196]

- Lanceheads (Bothrops)

- Bushmasters (Lachesis)

- Other Bothriopsis, Porthidium)[197]

Birds

- Trogons (Trogon)[199]

- Condors (Vultur gryphus, †Dryornis, †Geronogyps, †Wingegyps, †Perugyps)[200][201][202][n 33]

Mammals

- Small-eared shrews(Cryptotis) – only present in NW South America: Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru

- Rodents (Rodentia)

- Orthogeomys thaeleri) – one species, in Colombia

- Heteromyid mice (Heteromys) – only present in NW South America: Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador

- Cricetid – primarily sigmodontine – rats and mice (Cricetidae: Sigmodontinae) – the nonsigmodontines consist of two species present only in Colombia and Ecuador[n 34]

- Tree ) – present in northern and central South America

- Sylvilagus brasiliensis, S. floridanus, S. varynaensis) – present in northern and central South America

- Odd-toed ungulates (Perissodactyla)

- T. terrestris)

- Even-toed ungulates (Artiodactyla)

- Peccaries (†Sylvochoerus,[79] †Waldochoerus,[79] Tayassu pecari, Catagonus wagneri, Dicotyles tajacu)

- †)

- Pudu, Hippocamelus)

- )

- †Gomphotheres (Cuvieronius hyodon, Notiomastodon[n 36] platensis) – elephant relatives[83]

- Carnivorans (Carnivora)

- Otters (Lontra, Pteronura)

- Other mustelids (Mustelinae: Eira, Galictis, Lyncodon, Neogale)

- Hog-nosed skunks (Conepatus chinga, C. humboldtii, C. semistriatus)

- Bassaricyon, †Cyonasua, †Chapalmalania)

- Short-faced bears (Tremarctinae: Tremarctos ornatus, †Arctotherium)[206]

- Wolves (†Canis gezi, †C. nehringi, †A. dirus – the latter known only from as far south as southern Bolivia[207])[208][209]

- Gray fox[n 37] (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) – only present in NW South America: Colombia, Venezuela

- Other Lycalopex, Chrysocyon, Speothos)

- Small felids (Leopardus) – all 9 extant species (e.g. L. pardalis, L. wiedii)

- Cougar (Puma concolor) and jaguarundi (P. yagouaroundi)

- Jaguar (Panthera onca)

- †Scimitar cats (Xenosmilus, Homotherium) – known so far only from Uruguay[212] and Venezuela[213][214][215]

- †Saber-toothed cats (Smilodon gracilis,[215] S. fatalis,[216] S. populator)

- †American lion (Panthera leo atrox), reported from Peru[217] and Argentina and Chile;[218] however, the former set of remains has later been identified as belonging to a jaguar[219] and the latter set of remains were initially identified as being from jaguars

- Bats (Chiroptera)

- N. tumidirostris)

- Vespertilionid bats[59]

Image gallery

-

Amazonian palm viper, Bothrops bilineatus

-

Drymoreomys albimaculatus, a sigmodontine rodent

-

TheLama guanicoe

-

The coati Nasua nasua

-

Saber-toothed †Smilodon populator

See also

- Caribbean Plate § First American land bridge

- Central American Seaway

- Columbian Exchange

- List of mammals of the Caribbean

- List of mammals of Central America

- List of mammals of North America

- List of mammals of South America

- Lists of extinct animals by continent

Notes

- ^ During the Eocene, astrapotheres[19] and litopterns[20][21] were also present in Antarctica.

- perissodactyls.[22][23] Mitochondrial DNA obtained from Macrauchenia corroborates this and gives an estimated divergence date of 66 Ma ago.[24]

- ^ Once in Australia, facing less competition, marsupials diversified to fill a much larger array of niches than in South America, where they were largely carnivorous.

- ^ It is the sister group to a clade containing all other extant australidelphians (roughly 238 species).

- ^ Ziphodont (lateromedially compressed, recurved and serrated) teeth tend to arise in terrestrial crocodilians because, unlike their aquatic cousins, they are unable to dispatch their prey by simply holding them underwater and drowning them; they thus need cutting teeth with which to slice open their victims.

- ^ It is also notable that both simians (ancestral to monkeys) and hystricognath rodents (ancestral to caviomorphs) are believed to have arrived in Africa by rafting from Eurasia about 40 Ma ago.[58]

- ^ North American gopher tortoises are most closely related to the Asian genus Manouria.

- ^ An alternative explanation blames climatic and physiographic changes associated with the uplift of the Andes.[38]

- ^ Of the 6 families of North American rodents that did not originate in South America, only beavers and mountain beavers failed to migrate to South America. (However, human-introduced beavers have become serious pests in Tierra del Fuego.)

- chalicotheres, clawed perissodactyl herbivores ecologically similar to ground sloths, died out in North America in the Miocene about 9 Ma ago, while they survived to the early Pleistocene in Asia and Africa.[91]

- ^ Simpson, 1950, p. 382[93]

- ^ Marshall, 1988, p. 386[5]

- nutria/coypuhas been introduced to a number of North American locales.)

- African forest elephantas a separate species).

- ^ cervidgenera by continent are as follows: Canid genera by continent

- North America: 3 genera, 9 species – Canis, Urocyon, Vulpes

- Central America: 3 genera, 4 species – Canis, Speothos, Urocyon

- South America: 6 genera, 11 species –

- Eurasia: 4 genera, 12 species – Cuon, Nyctereutes, Vulpes

- Africa: 4 genera, 12 species – Otocyon, Vulpes

- North America: 4 genera, 5 species –

- Central America: 2 genera, 4 species – Mazama, Odocoileus

- South America: 6 genera, 16 species – Pudu

- Eurasia: 10 genera, 36 species – Muntiacus, Rangifer

- Africa: 1 genus, 1 species – Cervus

- ^ Including extinct genera, South America has hosted nine genera of cervids, eight genera of mustelids, and 10 genera of canids. However, some of this diversity of South American forms apparently arose in North or Central America prior to the interchange.[88] Significant disagreement exists in the literature concerning how much of the diversification of South America's canids occurred prior to the invasions. A number of studies concur that the grouping of endemic South American canids (excluding Urocyon and Canis, although sometimes transferring C. gezi to the South American group[98]) is a clade.[98][99][100] However, different authors conclude that members of this clade reached South America in at least two,[99] three to four,[98] or six[100] invasions from North America.

- Canis dirus, was present in South America until the end of the Pleistocene.

- ^ platyrrhine monkeys) are as follows: Central American opossum species

- Derby's woolly opossum (Caluromys derbianus)

- Water opossum (Chironectes minimus)

- Common opossum (Didelphis marsupialis)

- Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana)

- Mexican mouse opossum (Marmosa mexicana)

- Robinson's mouse opossum (Marmosa robinsoni)

- Panama slender opossum (Marmosops invictus)

- Brown four-eyed opossum (Metachirus nudicaudatus)

- Alston's mouse opossum (Micoureus alstoni)

- Sepia short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis adusta)

- Gray four-eyed opossum (Philander opossum)

- Grayish mouse opossum (Tlacuatzin canescens)

- Nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus)

- Northern naked-tailed armadillo (Cabassous centralis)

- Pygmy three-toed sloth (Bradypus pygmaeus)

- Brown-throated sloth (Bradypus variegatus)

- Hoffmann's two-toed sloth (Choloepus hoffmanni)

- Silky anteater (Cyclopes didactylus)

- Giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla)

- Northern tamandua (Tamandua mexicana)

- Rothschild's porcupine(Coendou rothschildi)

- Mexican hairy dwarf porcupine (Sphiggurus mexicanus)

- Lesser capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris)

- Coiban agouti (Dasyprocta coibae)

- Mexican agouti (Dasyprocta mexicana)

- Central American agouti (Dasyprocta punctata)

- Ruatan Island agouti (Dasyprocta ruatanica)

- Lowland paca (Cuniculus paca)

- Rufous soft-furred spiny-rat(Diplomys labilis)

- Armored rat (Hoplomys gymnurus)

- Tome's spiny-rat(Proechimys semispinosus)

- Coiba Island howler (Alouatta coibensis) – may be a subspecies of Alouatta palliata

- Mantled howler (Alouatta palliata)

- Guatemalan black howler(Alouatta pigra)

- Panamanian night monkey (Aotus zonalis) – may be a subspecies of gray-bellied night monkey (Aotus lemurinus)

- Black-headed spider monkey (Ateles fusciceps)

- Geoffroy's spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi)

- White-headed capuchin(Cebus capucinus)

- Geoffroy's tamarin (Saguinus geoffroyi)

- Cottontop tamarin(Saguinus oedipus) – possibly recently extirpated in Central America

- Central American squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedii)

- ^ During the Miocene alone, between about 23 and 5 Ma ago, 11 episodes of invasions of North America from Eurasia have been recognized, bringing a total of 81 new genera into North America.[88]

- ^ The combination of Africa, Eurasia and North America was termed the "World Continent" by George Gaylord Simpson.[93]

- ^ Simpson, 1950, p. 368[93]

- EQ (encephalization quotient, a measure of the brain to body size ratio adjusted for the expected effect of differences in body size) of fossil ungulates compiled by H. Jerison,[132] North American ungulates showed a trend towards greater EQs going from the Paleogene to the Neogene periods (average EQs of 0.43 and 0.64, respectively), while the EQs of South American ungulates were static over the same time interval (average EQ unchanged at 0.48).[18] This analysis was later criticized.[133] Jerison subsequently presented data suggesting that native South American ungulates also lagged in the relative size of their neocortices (a measurement not subject to the vagaries of body mass estimation).[134] Interestingly, the late survivor Toxodon had one of the highest EQ values (0.88) among native Neotropic ungulates.[133]

Jerison also found that Neogene xenarthrans had low EQs, similar to those he obtained for South American ungulates.[132] - ^ The estimated EQ of Thylacosmilus atrox, 0.41 (based on a brain mass of 43.2 g, a body mass of 26.4 kg,[135] and an EQ of 43.2/[0.12*26400^(2/3)][134]), is high for a sparassodont,[136] but is lower than that of modern felids, with a mean value of 0.87.[137] Estimates of 0.38[138] and 0.59[137] have been given for the EQ of much larger Smilodon fatalis (based on body mass estimates of 330 and 175 kg, respectively).

- giant tortoises of Asia and Africa[161] died out much earlier in the Quaternary than those of South America, Madagascar and Australia, while those of North America[162]died out around the same time.

- ^ P. S. Martin (2005), p. 175.[95]

- shrub-ox, were less fortunate).

- ^ Ma. Crossings by fish, arthropods, rafting amphibians and reptiles, and flying bats and birds were made before 10 Ma ago in many cases. Taxa listed as invasive did not necessarily cross the isthmus themselves; they may have evolved in the adopted land mass from ancestral taxa that made the crossing.

- ^ Mixotoxodon remains have been collected in Central America and Mexico as far north as Veracruz and Michoacán, with a possible find in Tamaulipas;[176] additionally, one fossil tooth has been identified in eastern Texas, United States.[177]

- Geoffroy's spider monkey.

- C. capucinus ~ 2 Ma ago; an invasion by A. zonalis and S. geoffroyi ~ 1 Ma ago; a most recent invasion by A. fusciceps. The species of the first wave have apparently been out-competed by those of the second, and now have much more restricted distributions.[187]

- Pangea, perhaps not long before it separated to become Laurasia,[179] and are not present anywhere else in the Southern Hemisphere (see the world salamander distribution map). In contrast, caecilians have a mostly Gondwanan distribution. Apart from a small region of overlap in southern China and northern Southeast Asia, Central America and northern South America are the only places in the world where both salamanders and caecilians are present.

- ^ Condors apparently reached South America by the late Miocene or early Pliocene (4.5 – 6.0 Ma ago), several million years before the formation of the isthmus.[202] Condor-like forms in North America date back to the Barstovian stage (middle Miocene, 11.8 – 15.5 Ma ago).[201]

- ^ This is based on the definition of Sigmodontinae that excludes Neotominae and Tylomyinae.

- Ma ago, has traditionally been thought to have evolved from pliohippines.[203][204] However, recent studies of the DNA of Hippidion and other New World Pleistocene horses indicate that Hippidion is actually a member of Equus, closely related to the extant horse, E. ferus.[203][204] Another invasion of South America by Equus occurred about one Ma ago, and this lineage, traditionally viewed as the subgenus Equus (Amerhippus), appears indistinguishable from E. ferus.[204] Both these lineages became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene, but E. ferus was reintroduced from Eurasia by Europeans in the 16th century. Note: the authors of the DNA sequence study of Equus (Amerhippus) use "E. caballus" as an alternative specific name for "E. ferus".[204]

- ^ Not to be confused with the South American gray fox.

- Quaternary extinction event that delivered the coup de grâceto the native Neotropic ungulates also dealt a heavy blow to South America's ungulate immigrants.

Change in number of South American ungulate genera over time[90] Time interval Source region of genera Geologic period Range ( Maago)South America North America Both Huayquerian 9.0–6.8 13 0 13 Montehermosan 6.8–4.0 12 1 13 Chapadmalalan 4.0–3.0 12 1 13 Uquian 3.0–1.5 5 10 15 Ensenadan 1.5–0.8 3 14 17 Lujanian 0.8–0.011 3 20 23 Holocene 0.011–0 0 11 11

References

- PMID 27540590.

- ^ .

- OCLC 556393.

- OCLC 556393.

- ^ Bibcode:1988AmSci..76..380M. Archived(PDF) from the original on 2013-03-02. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ^ Osborn, H. (1910). The Age Of Mammals In Europe, Asia, And North America. New York, EEUU: The Macmillan Company. pp. 80–81.

- ^ Karanth, K. Praveen (2006-03-25). "Out-of-India Gondwanan origin of some tropical Asian biota" (PDF). Current Science. 90 (6): 789–792. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

- doi:10.1130/G31585.1. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- S2CID 129644411.

- S2CID 238735010. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- S2CID 56382943.

- PMID 32011715. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- . Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- . Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Kapur, Vivesh V.; Carolin, N.; Bajpai, S. (2022). "Early Paleogene mammal faunas of India: a review of recent advances with implications for the timing of initial India-Asia contact". Himalayan Geology. 47 (1B): 337–356. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- PMID 11136239.

- S2CID 4336007. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ OCLC 5219346.

- S2CID 58908785.

- )

- S2CID 140177511.

- S2CID 4467386.

- PMID 25833851.

- PMID 28654082.

- S2CID 216591096.

- ^ PMID 20668664.

- S2CID 4350045.

- ^ Pascual, R.; Goin, F. J.; Balarino, L.; Sauthier, D. E. U. (2002). "New data on the Paleocene monotreme Monotrematum sudamericanum, and the convergent evolution of triangulate molars" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 47 (3): 487–492. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- PMID 12857645.

- S2CID 38890667.

- ^ Naish, Darren (29 June 2008). "Invasion of the marsupial weasels, dogs, cats and bears... or is it?". scienceblogs.com. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ^ Naish, Darren (2006-10-27). "Terror birds". darrennaish.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- .

- ^ Palmqvist, Paul; Vizcaíno, Sergio F. (2003-09-30). "Ecological and reproductive constraints of body size in the gigantic Argentavis magnificens (Aves, Theratornithidae) from the Miocene of Argentina" (PDF). Ameghiniana. 40 (3): 379–385. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ^ Paolillo, A.; Linares, O. J. (2007-06-05). "Nuevos Cocodrilos Sebecosuchia del Cenozoico Suramericano (Mesosuchia: Crocodylia)" (PDF). Paleobiologia Neotropical. 3: 1–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- JSTOR 4523070.

- ISBN 978-84-7840-707-1.

- ^ JSTOR 4522967.

- doi:10.25249/0375-7536.2010403330338 (inactive 2024-02-01). Retrieved 2017-10-23.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2024 (link - PMID 17884827.

- S2CID 83859607.

- PMID 24621950.

- ^ PMID 16551580. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ Mangels, J. (2011-10-15). "Case Western Reserve University expert uses fossil teeth to recast history of rodent". Cleveland Live, Inc. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- PMID 21993503.

- PMID 21238387.

- PMID 17500416.

- S2CID 54534830.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 198149958.

- S2CID 140178414.

- PMID 18495621.

- "Biggest rodent 'shrinks in size'". BBC News. 20 May 2008.

- S2CID 4456556.

- .

- S2CID 4445687.

- S2CID 215550773.

- S2CID 215551148.

- ^ PMID 22665790.

- ^ Universidade de Brasília: 391–410. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ PMID 24504061.

- ^ S2CID 25912333.

- ^ PMID 16678445. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2012-03-16. Retrieved 2012-04-12.

- hdl:2246/418.

- PMID 21126276.

- S2CID 55799145.

- PMID 18077239.

- PMID 20356885.

- S2CID 24210185.

- PMID 21125025.

- PMID 17174109.

- ^ S2CID 251050063.

- ^ S2CID 8625188.

- PMID 9491603.

- S2CID 22355532.

- PMID 23257216.

- S2CID 134089273.

- ^ Campbell, K. E.; Frailey, C. D.; Romero-Pittman, L. (2000). "The Late Miocene Gomphothere Amahuacatherium peruvium (Proboscidea: Gomphotheriidae) from Amazonian Peru: Implications for the Great American Faunal Interchange-[Boletín D 23]". Ingemmet.

- .

- ^ S2CID 85961848.

- ^ S2CID 55245294.

- .

- doi:10.3724/SP.J.1261.2013.00015 (inactive 31 January 2024). Retrieved 2020-01-23.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - ^ .

- S2CID 43163341.

- S2CID 174813630.

- ^ Morgan, Gary S. (2002), "Late Rancholabrean Mammals from Southernmost Florida, and the Neotropical Influence in Florida Pleistocene Faunas", in Emry, Robert J. (ed.), Cenozoic Mammals of Land and Sea: Tributes to the Career of Clayton E. Ray, Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology, vol. 93, Washington, D.C., pp. 15–38

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - .

- ^ S2CID 198152030.

- ^ Marshall, L. G.; Cifelli, R. L. (1990). "Analysis of changing diversity patterns in Cenozoic land mammal age faunas, South America". Palaeovertebrata. 19: 169–210. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ S2CID 88305955.

- AMNH. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- hdl:11336/56638.

- ^ JSTOR 27826322. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- ^ doi:10.22179/REVMACN.5.26. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2011-02-06.

- ^ OCLC 58055404.

- . Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- PMID 17790868.

- ^ S2CID 86650539.

- ^ S2CID 20763999.

- ^ S2CID 36185744.

- .

- S2CID 16700349.

- ^ OCLC 8409501.

- ISBN 978-1-4684-8853-1. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- ^ S2CID 134939823.

- ^ S2CID 15751319.

- S2CID 132584097.

- hdl:11336/94480.

- PMID 29298933.

- ^ S2CID 10161199.

- ^ S2CID 49473591.

- ^ S2CID 198190603.

- ^ S2CID 84680371.

- ^ S2CID 209308325.

- S2CID 53712751.

- PMID 17174109.

- ISBN 978-0-226-64919-1.

- ISSN 0036-8733.

- ^ OCLC 1012400051.

- ISSN 0091-7613.

- .

- S2CID 134344096.

- ^ hdl:11336/81756.

- PMID 27095265.

- S2CID 251052044.

- PMID 9851923.

- S2CID 130332367.

- S2CID 134902094.

- S2CID 213737574.

- OCLC 6331415.

- OCLC 25508994.

- ^ OCLC 700636.

- ^ PMID 7284752.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-392560-2.

- S2CID 85776991.

- PMID 3216103.

- ^ PMID 1181005.

- OCLC 700636.

- JSTOR 2389354.

- S2CID 4436119.

- JSTOR 1380307.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Gerszak, Jennie Rothenberg Gritz,Fen Montaigne,Rafal. "The Story of How Humans Came to the Americas Is Constantly Evolving". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - .

- ISBN 978-88-8080-025-5.

- S2CID 10395314.

- .

- .

- . Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- .

- PMID 16701402. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2014-05-25. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- S2CID 45643228. Retrieved 2011-08-26.

- PMID 26865301.

- .

- PMID 15288523.

- PMID 10731144.

- OCLC 41712246.

- hdl:10289/5404.

- S2CID 36583693.

- PMID 18719103.

- PMID 20713711.

- ISBN 978-90-481-9961-7.

- .

- PMID 16085711.

- S2CID 90558542.

- .

- S2CID 4249191.

- S2CID 186242235.

- OCLC 41368299. Retrieved 2015-11-07.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-306-42021-4.

- S2CID 10281132.

- S2CID 83925199. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- PMID 17548823.

- ^ PMID 19996168.

- .

- ^ . Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- .

- S2CID 53601518.

- PMID 10833043.[permanent dead link]

- ^ PMID 9667999.

- PMID 19278298.

- .

- S2CID 83972694.

- S2CID 86320083.

- PMID 12099801.

- ^ "Scelidotherium in the Paleobiology Database". Fossilworks. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- S2CID 27112941.

- ISBN 978-0-387-25854-6.

- PMID 24003317.

- ^ PMID 31039726. 20190148.

- S2CID 86086706.

- ^ PMID 23497060.

- . Retrieved 2008-01-11.

- .

- PMID 10764543.

- JSTOR 3893186.

- S2CID 86252575.

- JSTOR 1447591.

- PMID 11839192.

- S2CID 25090736.

- JSTOR 4523192.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 85805971.

- ^ PMID 15974804.

- ^ S2CID 19069554.

- ISBN 978-88-8080-025-5.

- .

- ^ "Canis dirus (dire wolf)". Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- S2CID 84760786.

- ISBN 978-0-520-09960-9. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ "New Clues To Extinct Falklands Wolf Mystery". EurekAlert. Science Daily. 2009-11-03. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- S2CID 205315969.

- ^ Mones, A.; Rinderknecht, A. (2004). "The First South American Homotheriini (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae)" (PDF). Comunicaciones Paleontologicas Museo Nacional de Historia Natural y Anthropologia. 2 (35): 201–212. Retrieved 2013-02-08.

- ^ Sanchez, Fabiola (2008-08-21). "Saber-toothed cat fossils discovered". Associated Press. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

- ^ Orozco, José (2008-08-22). "Sabertooth Cousin Found in Venezuela Tar Pit – A First". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved 2008-08-30.

- ^ S2CID 129693331.

- .

- OCLC 759120597.

- .

- ^ Seymour, K. 2015. Perusing Talara: Overview of the Late Pleistocene fossils from the tar seeps of Peru Archived 2018-10-01 at the Wayback Machine. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Science Series, 42: 97-109

Further reading

- Cione, A. L.; Gasparini, G. M.; Soibelzon, E.; Soibelzon, L. H.; Tonni, E. P. (24 April 2015). The Great American Biotic Interchange: A South American Perspective. Springer. OCLC 908103326.

- Croft, D. A. (29 August 2016). Horned Armadillos and Rafting Monkeys: The Fascinating Fossil Mammals of South America. Indiana University Press. OCLC 964782185.

- Defler, T. (19 December 2018). History of Terrestrial Mammals in South America: How South American Mammalian Fauna Changed from the Mesozoic to Recent Times. Springer. OCLC 1125820897.

- Fariña, R.A.; Vizcaíno, S.F.; De Iuliis, G. (2013). Megafauna: Giant Beasts of Pleistocene South America. Indiana University Press. OCLC 779244424.

- JSTOR 27826322. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Stehli, F. G.; Webb, S. D., eds. (2013). The Great American Biotic Interchange. Topics in Geobiology, vol. 4. Vol. 4. OCLC 968646442.

- Woodburne, M. O. (2010-07-14). "The Great American Biotic Interchange: Dispersals, Tectonics, Climate, Sea Level and Holding Pens". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 17 (4): 245–264. PMID 21125025. The biotic & geologic dynamics of the Great American Biotic Interchange are reviewed and revised.