Greater Iran

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| |

| History of Greater Iran | |

|---|---|

| 1407–1468 | |

| Aq Qoyunlu Turcomans | 1378–1508 |

| Safavid Empire | 1501–1722 |

| Mughal Empire | 1526–1857 |

| Hotak dynasty | 1722–1729 |

| Afsharid Iran | 1736–1750 |

| Zand dynasty | 1750–1794 |

| Durrani Empire | 1794–1826 |

| Qajar Iran | 1794–1925 |

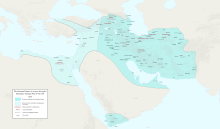

Greater Iran or Greater Persia (

Throughout the 16th–19th centuries, Iran lost many of the territories that had been conquered under the Safavids and Qajars. The Ottoman–Iranian Wars resulted in the loss of present-day Iraq to the Ottoman Empire, as outlined in the Treaty of Amasya in 1555 and the Treaty of Zuhab in 1639. Simultaneously, the Russo-Iranian Wars resulted in the loss of the Caucasus to the Russian Empire: the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813 saw Iran cede present-day Dagestan, Georgia, and most of Azerbaijan;[9][10][11] and the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828 saw Iran cede present-day Armenia, the remainder of Azerbaijan, and Iğdır, setting the northern boundary along the Aras River.[12][13] Parts of Afghanistan were lost to the British Empire through the Treaty of Paris in 1857 and the McMahon Arbitration in 1905.[14][15]

Etymology

The name "Iran", meaning "land of the

While up until the end of the

Definition

To the Ancient Greeks, Greater Iran ended at the Indus River located in Pakistan.[28]

According to J. P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams most of Western greater Iran spoke Southwestern Iranian languages in the Achaemenid era while the Eastern territory spoke Eastern Iranian languages related to Avestan.[29]

Primary sources, including Timurid historian Mir Khwand, define Iranshahr (Greater Iran) as extending from the Euphrates to the Oxus[32]

The Cambridge History of Iran takes a geographical approach in referring to the "historical and cultural" entity of "Greater Iran" as "areas of Iran, parts of Afghanistan, and Chinese and Soviet Central Asia".[33]

Background

Greater Iran is called Iranzamin (ایرانزمین) which means "Iranland" or "The Land of Iran". Iranzamin was in the mythical times as opposed to the Turanzamin the Land of Turan, which was located in the upper part of Central Asia.[35][verification needed]

With

- "Many Iranians consider their natural sphere of influence to extend beyond Iran's present borders. After all, Iran was once much larger. Portuguese forces seized islands and ports in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 19th century, the Russian Empire wrested from Washington Institute for Near East Policy[37]

- "Iran today is just a rump of what it once was. At its height, Iranian rulers controlled Iraq, Afghanistan, Western Pakistan, much of Central Asia, and the Caucasus. Many Iranians today consider these areas part of a greater Iranian sphere of influence." -Patrick Clawson[38]

- "Since the days of the Achaemenids, the Iranians had the protection of geography. But high mountains and the vast emptiness of the Iranian plateau were no longer enough to shield Iran from the Russian army or British navy. Both literally, and figuratively, Iran shrank. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Afghanistan were Iranian, but by the end of the century, all this territory had been lost as a result of European military action."[39]

Regions

In the 8th century, Iran was conquered by the

West Asia

Bahrain

From the 6th century BC to the 3rd century BC, Bahrain was a prominent part of the Persian Empire by the

In the 3rd century AD, the Sassanids succeeded the Parthians and controlled the area for four centuries until the Arab conquest.

By about 130 BC, the Parthian dynasty brought the Persian Gulf under their control and extended their influence as far as Oman. Because they needed to control the Persian Gulf trade route, the Parthians established garrisons along the southern coast of the Persian Gulf.[41] through warfare and economic distress, been reduced to only 60.[46] The influence of Iran was further undermined at the end of the 18th century when the ideological power struggle between the Akhbari-Usuli strands culminated in victory for the Usulis in Bahrain.[47]

An Afghan uprising led by Hotakis of Kandahar at the beginning of the 18th century resulted in the near-collapse of the Safavid state.[

In 1730, the new Shah of

During most of the second half of the eighteenth century, Bahrain was ruled by

Many names of villages in Bahrain are derived from the

In 1910, the Persian community funded and opened a

Historian Nasser Hussain says that many Iranians fled their native country in the early 20th century due to a law king Reza Shah issued which banned women from wearing the hijab, or because they feared for their lives after fighting the English or to find jobs. They were coming to Bahrain from Bushehr and the Fars province between 1920 and 1940. In the 1920s, local Persian merchants were prominently involved in the consolidation of Bahrain's first powerful lobby with connections to the municipality in an effort to contest the municipal legislation of British control.[55]

Bahrain's local Persian community has heavily influenced the country's local food dishes. One of the most notable local delicacies of the people in Bahrain is

Iraq

Throughout history, Iran always had strong cultural ties with the region of present-day Iraq. Mesopotamia is considered the cradle of civilization and the place where the first empires in history were established. These empires, namely the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian, dominated the ancient middle east for millennia, which explains the great influence of Mesopotamia on the Iranian culture and history, and it is also the reason why the later Iranian and Greek dynasties chose Mesopotamia to be the political center of their rule. For a period of around 500 years, what is now Iraq formed the core of Iran, with the Iranian Parthian and Sasanian empire having their capital in what is modern-day Iraq for the same centuries-long time span. (Ctesiphon)

Of the four residences of the Achaemenids named by Herodotus—Ecbatana, Pasargadae or Persepolis, Susa and Babylon—the last [situated in Iraq] was maintained as their most important capital, the fixed winter quarters, the central office of bureaucracy, exchanged only in the heat of summer for some cool spot in the highlands.[56] Under the

Sassanian double city of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.[56]— Iranologist Ehsan Yarshater, The Cambridge History of Iran,[56]

According to Iranologist Richard N. Frye:[57][58]

Throughout Iran's history the western part of the land has been frequently more closely connected with the

plateau to the east of the central deserts [the Dasht-e Kavir and Dasht-e Lut].— Richard N. Frye, The Golden Age of Persia: The Arabs in the East

Between the coming of the Abbasids [in 750] and the Mongol onslaught [in 1258], Iraq and western Iran shared a closer history than did eastern Iran and its western counterpart.

— Neguin Yavari, Iranian Perspectives on the Iran–Iraq War[58]

Testimony to the close relationship shared by Iraq and western Iran during the Abbasid era and later centuries, is the fact that the two regions came to share the same name. The western region of Iran (ancient Media) was called 'Irāq-e 'Ajamī ("Persian Iraq"), while central-southern Iraq (Babylonia) was called 'Irāq al-'Arabī ("Arabic Iraq") or Bābil ("Babylon").

For centuries the two neighbouring regions were known as "The Two Iraqs" ("al-'Iraqain"). The 12th century Persian poet Khāqāni wrote a famous poem Tohfat-ul Iraqein ("The Gift of the Two Iraqs"). The city of Arāk in western Iran still bears the region's old name, and Iranians still traditionally call the region between Tehran, Isfahan and Īlām "ʿErāq".

During the medieval ages, Mesopotamian and Iranian peoples knew each other's languages because of trade, and because Arabic was the language of religion and science at that time. The

The majority of inhabitants of Iraq know

Arabic, and from the time of the domination of Turkic people the Turkish languagehas also found currency.— Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru

Iraqi culture has commonalities with the

There are still cities and provinces in Iraq where the Persian names of the city are still retained – e.g.,

In the modern era, the Safavid dynasty of Iran briefly reasserted hegemony over Iraq in the periods of 1501–1533 and 1622–1638, losing Iraq to the Ottoman Empire on both occasions (via the Treaty of Amasya in 1555 and the Treaty of Zuhab in 1639). Ottoman hegemony over Iraq was reconfirmed in the Treaty of Kerden in 1746.

Following the fall of the Ba'athist regime in 2003 and the empowerment of Iraq's majority Shī'i community, relations with Iran have flourished in all fields. Iraq is today Iran's largest trading partner in regard to non-oil goods.[62]

Many Iranians were born in Iraq or have ancestors from Iraq,

Caucasus

North Caucasus

Dagestan remains the bastion of

South Caucasus

According to Tadeusz Swietochowski, the territories of Iran and the republic of Azerbaijan usually shared the same history from the time of ancient Media (ninth to seventh centuries b.c.) and the Persian Empire (sixth to fourth centuries b.c.).[65][page needed]

Intimately and inseparably intertwined histories for millennia, Iran irrevocably lost the territory that is nowadays Azerbaijan in the course of the 19th century. With the

Many localities in this region bear Persian names or names derived from Iranian languages and Azerbaijan remains by far Iran's closest cultural, religious, ethnic, and historical neighbor.

Central Asia

Superimposed on and overlapping with Chorasmia was Khorasan which roughly covered nearly the same geographical areas in Central Asia (starting from

Xinjiang

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (December 2015) |

The Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County regions of China harbored a Tajik population and culture.[77] Chinese Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County was always counted as a part of the Iranian cultural & linguistic continent with Kashgar, Yarkand, and Hotan bound to the Iranian history.[78]

See also

Notes and references

Explanatory footnotes

- .

- ^ For example, those regions and peoples in the North Caucasus that were not under direct Iranian rule.

- ^ Such as in the western parts of South Asia, Bahrain and Tajikistan.

Citation footnotes

- S2CID 162213219.

- ^ International Journal of Middle East Studies. (2007), 39: pp 307–309 Copyright © 2007 Cambridge University Press.

- ISBN 978-3-643-80049-7.

- ^ "Interview with Richard N. Frye (CNN)". Archived from the original on 2016-04-23.

- ^ Richard Nelson Frye, The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Oct. 1962), pp. 261–268 I use the term Iran in an historical context[...]Persia would be used for the modern state, more or less equivalent to "western Iran". I use the term "Greater Iran" to mean what I suspect most Classicists and ancient historians really mean by their use of Persia—that which was within the political boundaries of States ruled by Iranians.

- ^ "IRAN i. LANDS OF IRAN". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ISBN 978-90-04-10763-2.

- ^ "Columbia College Today". columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-11-27. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ India. Foreign and Political Dept. (1892). A Collection of Treaties, Engagements, and Sunnuds, Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries: Persia and the Persian Gulf. G. A. Savielle and P. M. Cranenburgh, Bengal Print. Co. pp. x (10).

treaty of gulistan.

- ISBN 978-1-4422-4146-6.

Persia lost all its territories to the north of the Aras River, which included all of Georgia, and parts of Armenia and Azerbaijan.

- ISBN 978-0-313-26257-9.

In 1813 Iran signed the Treaty of Gulistan, ceding Georgia to Russia.

- ISBN 978-0-203-93830-0.

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 329.

- ISBN 978-0-203-97682-1.

- ^ Sir Percy Molesworth Sykes (1915). A history of Persia, Volume 2. Macmillan and co. p. 469.

Macmahon arbitration persia.

- ^ William W. Malandra (2005-07-20). "ZOROASTRIANISM i. HISTORICAL REVIEW". Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- ^ Nicholas Sims-Williams. "EASTERN IRANIAN LANGUAGES". Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- ^ "IRAN". Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- ^ K. Hoffmann. "AVESTAN LANGUAGE I-III". Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- ^ "ĒRĀN-WĒZ". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ "ZOROASTER ii. GENERAL SURVEY". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ a b Ahmad Ashraf. "IRANIAN IDENTITY ii. PRE-ISLAMIC PERIOD". Retrieved 2011-01-14.

- ^ Ed Eduljee. "Haroyu". heritageinstitute.com. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Ed Eduljee. "Aryan Homeland, Airyana Vaeja, Location. Aryans and Zoroastrianism". heritageinstitute.com. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ^ Ed Eduljee. "Aryan Homeland, Airyana Vaeja, in the Avesta. Aryan lands and Zoroastrianism". heritageinstitute.com. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-56859-177-3p.xi

- ^ Richard Foltz, "Religions of the Silk Road: Premodern Patterns of globalization", Palgrave Macmillan, rev. 2nd edition, 2010. pg 27

- ^ J.M. Cook, "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of Their Empire" in Ilya Gershevitch, William Bayne Fisher, J. A. Boyle "Cambridge History of Iran", Vol 2. pg 250. Excerpt: "To the Greeks, Greater Iran ended at the Indus".

- ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5. pg 307: "Dialectically, Old Persian is regarded as a southwestern Iranian language in contrast to the east Iranian Avestan which covered most of the rest of Greater Iran. However, it is important to note that during the Achaemeid era, the official language of the empire was Aramaic, which was the mother tongue of the ancient [Iraqis], since it was the language of literature, religion, and science at that time. [Aramaic] language had a great impact on Persian and survived as the dominant language in the middle east until the [Islamic conquest].

- ^ George Lane, "Daily Life in the Mongol Empire", Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006. pg 10" The year following 1260 saw the empire irrevocably split but also signaled the emergence of the two greatest achievements of the house of Chinggis, namely the Yuan dynasty of greater China and the Il-Khanid dynasty of greater Iran.

- ^ Judith G. Kolbas, "The Mongols in Iran", Excerpt from 399: "Uljaytu, Ruler of Greater Iran from 1304 to 1317 A.D."

- ^ Mīr Khvānd, Muḥammad ibn Khāvandshāh, Tārīkh-i rawz̤at al-ṣafā. Taṣnīf Mīr Muḥammad ibn Sayyid Burhān al-Dīn Khāvand Shāh al-shahīr bi-Mīr Khvānd. Az rū-yi nusakh-i mutaʻaddadah-i muqābilah gardīdah va fihrist-i asāmī va aʻlām va qabāyil va kutub bā chāphā-yi digar mutamāyiz mībāshad.[Tehrān] Markazī-i Khayyām Pīrūz [1959-60]. ایرانشهر از کنار فرات تا جیهون است و وسط آبادانی عالم است. Iranshahr stretches from the Euphrates to the Oxus, and it is the center of the prosperity of the World.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. III: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods, Ehsan Yarshater, Review author[s]: Richard N. Frye, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 21, No. 3. (Aug. 1989), pp.415.

- ^ Numista: Ashrafi - Nader Afshar Type A2; Širâz mint.

- Dehkhoda, see under entry "Turan"

- ISBN 978-964-379-023-3, p.78

- ISBN 978-1-4039-6276-8p.9,10

- ISBN 978-1-4039-6276-8p.30

- ISBN 978-1-4039-6276-8p.31-32

- ^ Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient ... by Curtis E. Larsen p. 13

- ^ a b Bahrain by Federal Research Division, page 7

- ^ Robert G. Hoyland, Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam, Routledge 2001p28

- ^ a b c Security and Territoriality in the Persian Gulf: A Maritime Political Geography by Pirouz Mojtahed-Zadeh, page 119

- ^ a b Conflict and Cooperation: Zoroastrian Subalterns and Muslim Elites in ... By Jamsheed K. Choksy, 1997, page 75

- ^ Yoma 77a and Rosh Hashbanah, 23a

- ^ Juan Cole, Sacred Space and Holy War, IB Tauris, 2007 p52

- ^ Are the Shia Rising? Maximilian Terhalle, Middle East Policy, Volume 14 Issue 2 Page 73, June 2007

- ^ Autobiography of Sheikh Yusuf Al Bahrani published in Interpreting the Self, Autobiography in the Arabic Literary Tradition, Edited by Dwight F. Reynolds, University of California Press Berkeley 2001

- ^ The Autobiography of Yūsuf al-Bahrānī (1696–1772) from Lu'lu'at al-Baḥrayn, from the final chapter An Account of the Life of the Author and the Events That Have Befallen Him featured in Interpreting the Self, Autobiography in the Arabic Literary Tradition, Edited by Dwight F. Reynolds, University of California Press Berkeley 2001 p221

- ^ Charles Belgrave, The Pirate Coast, G. Bell & Sons, 1966 p19

- ^ Ahmad Mustafa Abu Hakim, History of Eastern Arabia 1750–1800, Khayat, 1960, p78

- ^ James Onley, The Politics of Protection in the Gulf: The Arab Rulers and the British Resident in the Nineteenth Century, Exeter University, 2004 p44

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7103-0024-9.

- ^ Shirawi, May Al-Arrayed (1987). Education in Bahrain - 1919-1986, An Analytical Study of Problems and Progress (PDF). Durham University. p. 60.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-51435-4.

- ^ Sassanian double city of Seleucia-Ctesiphon.

- ISBN 978-0-7538-0944-0.

[..] throughout Iran's history the western part of the land has been frequently more closely connected with the lowlands of Mesopotamia than with the rest of the plateau to the east of the central deserts.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8130-1476-0.

Between the coming of the 'Abbasids and the Mongol onslaught, Iraq and western Iran shared a closer history than did eastern Iran and its western counterpart.

- ^ Morony, Michael G. "IRAQ AND ITS RELATIONS WITH IRAN". IRAQ i. IN THE LATE SASANID AND EARLY ISLAMIC ERAS. Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

Persian remained the language of most of the sedentary people as well as that of the chancery until the 15th century and thereafter, as attested by Ḥāfeẓ-e Abru (d. 1430) who said, "The majority of inhabitants of Iraq know Persian and Arabic, and from the time of the domination of Turkic people the Turkish language has also found currency: as the city people and those engaged in trade and crafts are Persophone, the Bedouins are Arabophone, and the governing classes are Turkophone. But, all three peoples (qawms) know each other's languages due to the mixture and amalgamation."

- ISBN 978-0-415-30804-5.

- ^ See: محمدی ملایری، محمد: فرهنگ ایران در دوران انتقال از عصر ساسانی به عصر اسلامی، جلد دوم: دل ایرانشهر، تهران، انتشارات توس 1375.: Mohammadi Malayeri, M.: Del-e Iranshahr, vol. II, Tehran 1375 Hs.

- ^ "Iraq plans to send 200-member trade delegation to Iran". Tehran Times. 9 January 2013. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Regional developments are leading to convergence of nations: Ahmadinejad". Mehr News Agency. 31 August 2007. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ Encyclopædia Iranica: "Caucasus Iran" article, p.84-96.

- ^ Historical Background Vol. 3, Colliers Encyclopedia CD-ROM, 02-28-1996

- ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3.

- ISBN 978-0-89774-940-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7425-0063-1.

- ISBN 978-0-415-78153-4.

- ISBN 978-975-6782-18-7.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 978-0-465-04576-1.]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[permanent dead link - ISBN 978-90-04-09796-4.

- ISBN 978-0-933273-95-5.

- JSTOR 24048765.

- ISBN 978-0-313-30731-7, p.28

- ^

Lorentz, J. Historical Dictionary of Iran. 1995. ISBN 978-0-8108-2994-7

- Iran-China Relationsfor more on the historical ties.

- collection under DS 266 N336 2005.

General references

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: ISBN 978-0-521-20095-0.

- ISBN 978-0-19-933549-7.

- Marcinkowski, Christoph (2010). Shi'ite Identities: Community and Culture in Changing Social Contexts. Berlin: Lit Verlag 2010. ISBN 978-3-643-80049-7.