Large Magellanic Cloud

| Large Magellanic Cloud | |

|---|---|

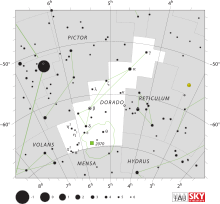

A map of the Large Magellanic Cloud with the brightest features annotated | |

| Observation data (J2000 epoch) | |

| Constellation | Dorado/Mensa |

| Right ascension | 05h 23m 34s[1] |

| Declination | −69° 45.4′[1] |

| Distance | 163,000 light-years (49.97 kpc)[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 0.13[1] |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | SB(s)m[1] |

| Mass | 1×1010 (excluding dark matter), 1.38×1011[3] (including dark matter). M☉ |

| Number of stars | 20 billion[5] |

| Size | 9.86 kpc (32,200 ly)[1] (diameter; 25.0 mag/arcsec2 B-band isophote)[4] |

| Apparent size (V) | 10.75° × 9.17°[1] |

| Other designations | |

| LMC, ESO 56- G 115, PGC 17223,[1] Nubecula Major[6] | |

The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) is a

The LMC is classified as a

With a

The LMC is predicted to merge with the Milky Way in approximately 2.4 billion years.[15]

History of observation

Both the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds have been easily visible for southern nighttime observers well back into prehistory. It has been claimed that the first known written mention of the Large Magellanic Cloud was by the

The first confirmed recorded observation was in 1503–1504 by

Ferdinand Magellan sighted the LMC on his voyage in 1519 and his writings brought it into common Western knowledge. The galaxy now bears his name.[18] The galaxy and southern end of Dorado are in the current epoch at opposition on about 5 December when thus visible from sunset to sunrise from equatorial points such as Ecuador, the Congos, Uganda, Kenya and Indonesia and for part of the night in nearby months. Above about 28° south, such as most of Australia and South Africa, the galaxy is always sufficiently above the horizon to be considered properly circumpolar, thus during spring and autumn the cloud is also visible much of the night, and the height of winter in June nearly coincides with closest proximity to the Sun's apparent position.

Measurements with the Hubble Space Telescope, announced in 2006, suggest the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds may be moving too quickly to be orbiting the Milky Way.[22]

Astronomers discovered a new black hole inside the Large Magellanic Cloud in November 2021 using the

Geometry

The Large Magellanic Cloud has a prominent central bar and

The LMC was long considered to be a planar galaxy that could be assumed to lie at a single distance from the Solar System. However, in 1986, Caldwell and Coulson who calculated distances to a sample of clusters and showed that the cluster system is distributed in the same plane as the field stars.

Distance

Distance to the LMC has been calculated using

Modern

In 2006, the Cepheid absolute luminosity was re-calibrated using Cepheid variables in the galaxy Messier 106 that cover a range of metallicities.[8] Using this improved calibration, they find an absolute distance modulus of , or 48 kpc (160,000 light-years). This distance has been confirmed by other authors.[9][10]

By cross-correlating different measurement methods, one can bound the distance; the residual errors are now less than the estimated size parameters of the LMC.

The results of a study using late-type eclipsing binaries to determine the distance more accurately was published in the scientific journal Nature in March 2013. A distance of 49.97 kpc (163,000 light-years) with an accuracy of 2.2% was obtained.[2]

Features

Like many

The LMC has a wide range of galactic objects and phenomena that make it known as an "astronomical treasure-house, a great celestial laboratory for the study of the growth and evolution of the stars", per

A bridge of gas connects the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) with the LMC, which evinces tidal interaction between the galaxies.[42] The Magellanic Clouds have a common envelope of neutral hydrogen, indicating that they have been gravitationally bound for a long time. This bridge of gas is a star-forming site.[43]

X-ray sources

No X-rays above background were detected from either cloud during the September 20, 1966,

Another was launched from same atoll at 11:32 UTC on October 29, 1968, to scan the LMC for X-rays.

The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) appears in the constellations

DEM L316 in the Cloud consists of two supernova remnants.[52] Chandra X-ray spectra show that the hot gas shell on the upper left has an abundance of iron. This implies that the upper-left SNR is the product of a Type Ia supernova; much lower such abundance in the lower remnant belies a Type II supernova.[52]

A 16 ms X-ray pulsar is associated with SNR 0538-69.1.[53] SNR 0540-697 was resolved using ROSAT.[54]

Gallery

-

Part of the SMASH dataset showing a wide-angle view of the Large Magellanic Cloud[55]

-

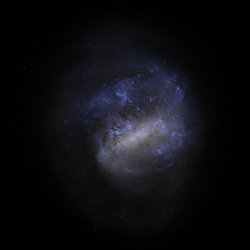

Large Magellanic Cloud as photographed by an amateur astronomer. Unrelated stars have been edited out.

-

Large Magellanic Cloud rendered from Gaia EDR3

-

Large Magellanic Cloud rendered from Gaia EDR3 without foreground stars

-

Revisiting a Celestial Fireworks Display Shreds, from theWide Field Planetary Camera 2. The delicate sheets and intricate filaments are debris from the cataclysmic death of a massive star that once lived in the LMC.[56]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database". Results for Large Magellanic Cloud. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ S2CID 4417699.

- .

- ^ Bibcode:1991rc3..book.....D.

- ISBN 978-3-03-010380-4.

- Bibcode:1954ASPL....7....9B.

- S2CID 854729.

- ^ S2CID 15728812.

- ^ S2CID 119263173.

- ^ Bibcode:2011JAVSO..39..122M.

- ^ "Magellanic Cloud". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ISBN 9780321595584.

- S2CID 118462693.

- ^ Sessions, Larry (December 8, 2021). "The Magellanic Clouds, our galactic neighbors". EarthSky. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ "Cloaked in red". ESA / HUBBLE. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ "Observatoire de Paris (Abd-al-Rahman Al Sufi)". Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ a b "Observatoire de Paris (LMC)". Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ISBN 9781441981615, retrieved November 13, 2019

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. Star Tales – al-Sufi's nebulae. Online edition. Retrieved 2021-09-15.

- ^ "Observatoire de Paris (Amerigo Vespucci)". Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ "Press release: Magellanic Clouds May Be Just Passing Through". Harvard University. January 9, 2007.

- ^ Ashley Strickland (11 November 2021). "Hidden black hole discovered in our neighboring galaxy". CNN. Retrieved 2021-11-18.

- ISBN 0-521-59270-4.

- S2CID 4368706.

- ^ "Precisely determined rotation rate of this galaxy will blow your mind". Science Recorder. Archived from the original on 2014-02-21.

- .

- S2CID 15818077.

- S2CID 121615519.

- ^ S2CID 15850335.

- S2CID 7266377.

- ^ .

- doi:10.1086/116074.

- S2CID 14921511.

- Bibcode:2006MmSAI..77..156M.

- ^ "The Odd Couple". ESO Press Release. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ISBN 0-07-228249-5.

- ISBN 0-486-23567-X.

- ^ Burnham (1978), 840–848.

- ISSN 0004-637X.

- ^ "A youthful cluster". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Mathewson D. S., Ford V. L. (1984). S. van den Bergh; K. S. de Boer (eds.). "Structure and Evolution of the Magellanic Clouds". IAU Symposium. 108. Reidel, Dordrecht: 125.

- S2CID 8240730.

- doi:10.1086/149312.

- ^ doi:10.1086/149343.

- ^ doi:10.1086/180322.

- S2CID 4187949.

- doi:10.1086/110966.

- ^ doi:10.1086/180773.

- doi:10.1086/181564.

- Bibcode:1989A&A...213...97B.

- ^ S2CID 17863461.

- S2CID 15812971.

- ISSN 0004-6280.

- ^ "Dark Energy Camera Snaps Deepest Photo yet of Galactic Siblings". noirlab.edu. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "Revisiting a Celestial Fireworks Display". Retrieved 2023-08-24.

- ^ "A long-dead star". www.spacetelescope.org. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

![Part of the SMASH dataset showing a wide-angle view of the Large Magellanic Cloud[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/51/Deepest%2C_widest_view_of_the_Large_Magellanic_Cloud_from_SMASH.jpg/250px-Deepest%2C_widest_view_of_the_Large_Magellanic_Cloud_from_SMASH.jpg)

![Revisiting a Celestial Fireworks Display Shreds, from the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2. The delicate sheets and intricate filaments are debris from the cataclysmic death of a massive star that once lived in the LMC.[56]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Revisiting_a_Celestial_Fireworks_Display_%28potw2248a%29.jpg/250px-Revisiting_a_Celestial_Fireworks_Display_%28potw2248a%29.jpg)

![DEM L316A is located some 160,000 light-years away in the Large Magellanic Cloud[57]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/A_long-dead_star_DEM_L316A.jpg/250px-A_long-dead_star_DEM_L316A.jpg)