Greek mathematics

Greek mathematics refers to mathematics texts and ideas stemming from the Archaic through the Hellenistic and Roman periods, mostly from the 5th century BC to the 6th century AD, around the shores of the Mediterranean.[1][2] Greek mathematicians lived in cities spread over the entire region, from Anatolia to Italy and North Africa, but were united by Greek culture and the Greek language.[3] The development of mathematics as a theoretical discipline and the use of deductive reasoning in proofs is an important difference between Greek mathematics and those of preceding civilizations.[4][5]

Origins and etymology

Greek mathēmatikē ("mathematics") derives from the

The origins of Greek mathematics are not well documented.[8][9] The earliest advanced civilizations in Greece and Europe were the Minoan and later Mycenaean civilizations, both of which flourished during the 2nd millennium BC. While these civilizations possessed writing and were capable of advanced engineering, including four-story palaces with drainage and beehive tombs, they left behind no mathematical documents.

Though no direct evidence is available, it is generally thought that the neighboring Babylonian and Egyptian civilizations had an influence on the younger Greek tradition.[10][11][8] Unlike the flourishing of Greek literature in the span of 800 to 600 BC, not much is known about Greek mathematics in this early period—nearly all of the information was passed down through later authors, beginning in the mid-4th century BC.[12][13]

Archaic and Classical periods

Greek mathematics allegedly began with

An equally enigmatic figure is Pythagoras of Samos (c. 580–500 BC), who supposedly visited Egypt and Babylon,[13][16] and ultimately settled in Croton, Magna Graecia, where he started a kind of brotherhood. Pythagoreans supposedly believed that "all is number" and were keen in looking for mathematical relations between numbers and things.[17] Pythagoras himself was given credit for many later discoveries, including the construction of the five regular solids. However, Aristotle refused to attribute anything specifically to Pythagoras and only discussed the work of the Pythagoreans as a group.[18][19]

Almost half of the material in Euclid's Elements is customarily attributed to the Pythagoreans, including the discovery of irrationals, attributed to Hippasus (c. 530–450 BC) and Theodorus (fl. 450 BC).[20] The greatest mathematician associated with the group, however, may have been Archytas (c. 435-360 BC), who solved the problem of doubling the cube, identified the harmonic mean, and possibly contributed to optics and mechanics.[20][21] Other mathematicians active in this period, not fully affiliated with any school, include Hippocrates of Chios (c. 470–410 BC), Theaetetus (c. 417–369 BC), and Eudoxus (c. 408–355 BC).

Greek mathematics also drew the attention of philosophers during the Classical period. Plato (c. 428–348 BC), the founder of the Platonic Academy, mentions mathematics in several of his dialogues.[22] While not considered a mathematician, Plato seems to have been influenced by Pythagorean ideas about number and believed that the elements of matter could be broken down into geometric solids.[23] He also believed that geometrical proportions bound the cosmos together rather than physical or mechanical forces.[24] Aristotle (c. 384–322 BC), the founder of the Peripatetic school, often used mathematics to illustrate many of his theories, as when he used geometry in his theory of the rainbow and the theory of proportions in his analysis of motion.[24] Much of the knowledge about ancient Greek mathematics in this period is thanks to records referenced by Aristotle in his own works.[13][25]

Hellenistic and Roman periods

The

Greek mathematics and astronomy reached its acme during the Hellenistic and early

Several centers of learning appeared during the Hellenistic period, of which the most important one was the

Later mathematicians in the Roman era include Diophantus (c. 214–298 AD), who wrote on polygonal numbers and a work in pre-modern algebra (Arithmetica),[37][38] Pappus of Alexandria (c. 290–350 AD), who compiled many important results in the Collection,[39] Theon of Alexandria (c. 335–405 AD) and his daughter Hypatia (c. 370–415 AD), who edited Ptolemy's Almagest and other works,[40][41] and Eutocius of Ascalon (c. 480–540 AD), who wrote commentaries on treatises by Archimedes and Apollonius.[42] Although none of these mathematicians, save perhaps Diophantus, had notable original works, they are distinguished for their commentaries and expositions. These commentaries have preserved valuable extracts from works which have perished, or historical allusions which, in the absence of original documents, are precious because of their rarity.[43][44]

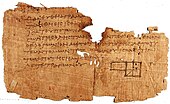

Most of the mathematical texts written in Greek survived through the copying of manuscripts over the centuries. While some fragments dating from antiquity have been found above all in Egypt, as a rule they do not add anything significant to our knowledge of Greek mathematics preserved in the manuscript tradition.[29]

Achievements

Greek mathematics constitutes an important period in the history of

Eudoxus of Cnidus developed a theory of proportion that bears resemblance to the modern theory of real numbers using the Dedekind cut, developed by Richard Dedekind, who acknowledged Eudoxus as inspiration.[48][49][50][51]

Euclid, who presumably wrote on optics, astronomy, and harmonics, collected many previous mathematical results and theorems in the Elements, a canon of geometry and elementary number theory for many centuries.[52][53][54]

The most characteristic product of Greek mathematics may be the theory of

Ancient Greek mathematics was not limited to theoretical works but was also used in other activities, such as business transactions and in land mensuration, as evidenced by extant texts where computational procedures and practical considerations took more of a central role.[11][63]

Transmission and the manuscript tradition

Although the earliest Greek language texts on mathematics that have been found were written after the Hellenistic period, many of these are considered to be copies of works written during and before the Hellenistic period.[64] The two major sources are

- Byzantine codices, written some 500 to 1500 years after their originals, and

- Syriac or Arabic translations of Greek works and Latin translations of the Arabic versions.

Nevertheless, despite the lack of original manuscripts, the dates of Greek mathematics are more certain than the dates of surviving Babylonian or Egyptian sources because a large number of overlapping chronologies exist. Even so, many dates are uncertain; but the doubt is a matter of decades rather than centuries.

The following works are extant only in Arabic translations:[66][67]

- Apollonius, Conics books V to VII

- Apollonius, Cutting Off of a Ratio

- Archimedes, Book of Lemmas

- Archimedes, Construction of the Regular Heptagon

- Diocles, On Burning Mirrors

- Diophantus, Arithmetica books IV to VII

- Euclid, On Divisions of Figures

- Euclid, On Weights

- Hero, Catoptrica

- Hero, Mechanica

- Menelaus, Sphaerica

- Pappus, Commentary on Euclid's Elements book X

- Ptolemy, Optics (extant in Latin from an Arabic translation of the Greek)

- Ptolemy, Planisphaerium

See also

- Al-Mansur – 2nd Abbasid caliph (r. 754–775)

- Chronology of ancient Greek mathematicians

- Greek numerals

- History of geometry – Historical development of geometry

- History of mathematics

- Timeline of ancient Greek mathematicians

- List of Greek mathematicians

Notes

- .

- ^ Netz, Reviel (2002). "Greek mathematics: A group picture". Science and Mathematics in Ancient Greek Culture. pp. 196–216. Retrieved 2024-03-04.

- ISBN 0-471-09763-2.

- ^ Knorr, W. (2000). Mathematics. Greek Thought: A Guide to Classical Knowledge: Harvard University Press. pp. 386–413.

- ISBN 978-3-945561-23-2, retrieved 2021-03-27

- S2CID 3994109.

- ^ Furner, J. (2020). "Classification of the sciences in Greco-Roman antiquity". www.isko.org. Retrieved 2023-01-09.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-852937-8.

- ^ Knorr, W. (1981). On the early history of axiomatics: The interaction of mathematics and philosophy in Greek Antiquity. D. Reidel Publishing Co. pp. 145–186. Theory Change, Ancient Axiomatics, and Galileo's Methodology, Vol. 1

- ^ Kahn, C. H. (1991). Some remarks on the origins of Greek science and philosophy. Science and Philosophy in Classical Greece: Garland Publishing Inc. pp. 1–10.

- ^ a b Høyrup, J. (1990). "Sub-scientific mathematics: Undercurrents and missing links in the mathematical technology of the Hellenistic and Roman world" (PDF) (Unpublished manuscript, written for Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt).

- ISBN 978-3-11-019432-6.

- ^ a b c Boyer & Merzbach (2011) pp. 40–89.

- S2CID 59435003.

- ISBN 0471543977.

- ^ Heath (2003) pp. 36–111

- ISBN 0471543977.

- ISSN 1984-8234.

- ^ Hans-Joachim Waschkies, "Introduction" to "Part 1: The Beginning of Greek Mathematics" in Classics in the History of Greek Mathematics, pp. 11–12

- ^ ISBN 978-1-107-01439-8, retrieved 2021-05-26

- S2CID 146652622.

- ISBN 978-90-04-46722-4.

- JSTOR 20123223.

- ^ ISBN 9780226482057.

- ^ Mendell, Henry (26 March 2004). "Aristotle and Mathematics". Stanford Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ (Boyer 1991, "Euclid of Alexandria" p. 119)

- JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt130jt89.

- ISBN 978-3-642-18904-3

- ^ a b Jones, A. (1994). "Greek mathematics to AD 300". Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences: Volume One. pp. 46–57. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ^ "Hellenistic Mathematics". The Story of Mathematics - A History of Mathematical Thought from Ancient Times to the Modern Day. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- S2CID 170916259.

- S2CID 122403901.

- ^ Russo, Lucio (2004). The Forgotten Revolution. Berlin: Springer. pp. 273–277.

- JSTOR 23040930.

- ISBN 978-3-11-054193-9.

- ISBN 978-0-19-973414-6. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ISSN 0315-0860.

- ISSN 0315-0860.

- doi:10.26021/3834.

- ^ Lambrou, M. (2003). "Theon of Alexandria and Hypatia". History of the Ancient World. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ISSN 2159-3159.

- ISBN 978-90-04-32105-2.

- ISBN 978-90-04-32105-2.

- ^ Heath, Thomas (1921). A History of Greek Mathematics. Humphrey Milford.

- ISBN 978-1-4939-3264-1

- ^ Knorr, W. (1996). The method of indivisibles in Ancient Geometry. Vita Mathematica: MAA Press. pp. 67–86.

- ^ Powers, J. (2020). Did Archimedes do calculus? History of Mathematics Special Interest Group of the MAA [1]

- S2CID 46974744.

- ^ Wigderson, Y. (April 2019). Eudoxus, the most important mathematician you've never heard of. https://web.stanford.edu/~yuvalwig/math/teaching/Eudoxus.pdf Archived 2021-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Filep, L. (2003). "Proportion theory in Greek mathematics". Acta Mathematica Academiae Paedagogicae Nyí regyháziensis. 19: 167–174.

- MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St. Andrews. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-387-98423-0.

- ISSN 0007-0882.

- ^ Pierce, D. (2015). The Foundations of Arithmetic in Euclid.

- S2CID 120954547.

- JSTOR 2691014.

- S2CID 147307969.

- JSTOR 27956431.

- ISSN 1600-0498.

- S2CID 226745369, retrieved 2021-03-27

- ISSN 1600-0498.

- ^ Duke, D. (2011). "The very early history of trigonometry" (PDF). DIO: The International Journal of Scientific History. 17: 34–42.

- S2CID 144052363.

- ^ J J O'Connor and E F Robertson (October 1999). "How do we know about Greek mathematics?". The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St. Andrews. Archived from the original on 30 January 2000. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- S2CID 21519829.

- S2CID 146539132.

- .

References

- ISBN 978-0-691-02391-5

- ISBN 978-0-471-54397-8

- Jean Christianidis, ed. (2004), Classics in the History of Greek Mathematics, Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-4020-0081-2

- Cooke, Roger (1997), The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course, Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-18082-1

- ISBN 978-0-309-09657-7

- ISBN 978-0-387-95336-6

- Burton, David M. (1997), The History of Mathematics: An Introduction (3rd ed.), The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., ISBN 978-0-07-009465-9

- ISBN 978-0-486-24073-2

- ISBN 978-0-486-43231-1

- Sing, Robert; van Berkel Tazuko; Osborne, Robin (2021), Numbers and Numeracy in the Greek Polis, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-46722-4

- Szabo, Arpad (1978) [First published 1978], The Beginnings of Greek Mathematics, Reidel & Akademiai Kiado, ISBN 978-963-05-1416-3