Guðrøðr Óláfsson

| Guðrøðr Óláfsson | |

|---|---|

| King of Dublin and the Isles | |

Expugnatio Hibernica): "Gottredum"[1] | |

| Reign | 1150s–1160 |

| Died | 10 November 1187 St Patrick's Isle |

| Burial | 1188 |

| Spouse | Findguala Nic Lochlainn |

| Issue |

|

| House | Crovan dynasty |

| Father | Óláfr Guðrøðarson |

| Mother | Affraic ingen Fergusa |

Guðrøðr Óláfsson (died 10 November 1187) was a twelfth-century ruler of the kingdoms of

In the last year of his father's reign, Guðrøðr was absent at the court of

Guðrøðr appears to have spent his exile in the kingdoms of

Background

Guðrøðr was a son of

The thirteenth- to fourteenth-century

Another alliance involving Óláfr was that with

Early career

Although the Chronicle of Mann portrays Óláfr's reign as one of tranquillity,

The following year marked a watershed in the history for the Kingdom of the Isles. For not only did David die late in May,

Guðrøðr's reliance upon Norwegian assistance, instead of support from his maternal-grandfather, could suggest that the attack upon Galloway was more successful than the compiler of the chronicle cared to admit.

Contested kingship

Midway through the twelfth-century,

The defeat of forces drawn from the Isles, and Muirchertach's subsequent spread of power into Dublin, may have had severe repercussions concerning Guðrøðr's career.[88] In 1155 or 1156, the Chronicle of Mann reveals that Somairle conducted a coup against Guðrøðr, specifying that Þorfinnr Óttarsson, one of the leading men of the Isles, produced Somairle's son, Dubgall, as a replacement to Guðrøðr's rule.[89] Somairle's stratagem does not appear to have received unanimous support, however, as the chronicle specifies that the leading Islesmen were made to render pledges and surrender hostages unto him, and that one such chieftain alerted Guðrøðr of Somairle's treachery.[90]

Late in 1156, on the night of 5/6 January, Somairle and Guðrøðr finally clashed in a bloody but inconclusive sea-battle. According to the chronicle, Somairle's fleet numbered eighty ships, and when the fighting concluded, the feuding brothers-in-law divided the Kingdom of the Isles between themselves.[92][note 6] Although the precise partitioning is unrecorded and uncertain, the allotment of lands seemingly held by Somairle's descendants in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries could be evidence that he and his son gained the southernmost islands of the Hebrides, whilst Guðrøðr retained the northernmost.[95] Two years later the chronicle reveals that Somairle, with a fleet of fifty-three ships, attacked Mann and drove Guðrøðr from the kingship into exile.[96] According to the thirteenth-century Orkneyinga saga, the contemporary Orcadian warlord Sveinn Ásleifarson had connections in the Isles, and overcame Somairle in battle at some point in the twelfth century. Although this source's account of Sveinn and Somairle is clearly somewhat garbled, it could be evidence that Sveinn aided Guðrøðr in his struggle against Somairle.[97] With Guðrøðr gone, it appears that either Dubgall or Somairle became King of the Isles.[98] Although the young Dubgall may well have been the nominal monarch, the chronicle makes it clear that it was Somairle who possessed the real power.[99] Certainly, Irish sources regarded Somairle as king by the end of his career.[98] The reason why the Islesmen specifically sought Dubgall as their ruler instead of Somairle is unknown. Evidently, Somairle was somehow an unacceptable candidate,[100] and it is possible that Ragnhildr's royal ancestry lent credibility to Dubgall that Somairle lacked himself.[101]

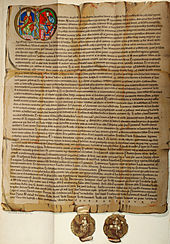

Exile from the Isles

Contemporaneous sources reveal that, upon his expulsion, Guðrøðr attempted to garner royal support in England and Scotland. For example, the English Pipe rolls record that, in 1158, the sheriffs of Worcester and Gloucester received allowances for payments made to Guðrøðr for arms and equipment.[103] Guðrøðr may have arrived in England by way of Wales. The English Crown's recent use of naval forces off the Gwynedd coast, as well as Guðrøðr's own familial links with the king himself, may account for the Guðrøðr's attempts to secure English assistance.[104] In any case, Guðrøðr was unable to gain Henry II's help, and the latter proceeded to busy himself in Normandy.[105] Guðrøðr next appears on record in Scotland, the following year, when he witnessed a charter of Malcolm to Kelso Abbey.[106] The fact that the Scottish Crown had faced opposition from Somairle in 1153 could suggest that Malcolm was sympathetic to Guðrøðr's plight.[107] Although the latter was certainly honourably treated by the Scots, as revealed by his prominent place amongst the charter's other witnesses, he was evidently unable to secure military support against Somairle.[108]

It is uncertain why Guðrøðr did not turn to his grandfather, Fergus, for aid. One possibility is that the defeat of the Gallovidian fleet in 1154 severely weakened the latter's position in Galloway. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that Galloway endured a bitter power struggle later that decade.[108][note 7] According to the twelfth- to thirteenth-century Chronicle of Holyrood, Malcolm overcame certain "confederate enemies" in Galloway in 1160.[111] Although the exact identities of these opponents are unknown, it is possible that this source documents a Scottish victory over an alliance between Somairle and Fergus.[112] Before the end of the year, Fergus retired to Holyrood Abbey,[113] and Somairle came into the king's peace.[114] Although the concordat between the Scottish Crown and Somairle may have taken place after the Malcolm's subjugation of Somairle and Fergus, an alternate possibility is that the agreement was concluded in the context of Somairle having aided the Scots in their overthrow of Fergus.[115] Somairle's deal with Scottish Crown may also have been undertaken not only in an effort to ensure that his own authority in the Isles was recognised by Malcolm, but to limit any chance of Guðrøðr receiving future royal support from the Scots.[116]

Having failed to secure substantial support in England and Scotland, Guðrøðr appears to have turned to Ingi, his nominal Norwegian overlord.

Return to the Isles

Somairle was slain in an unsuccessful invasion of mainland Scotland in 1164.[131] The declaration in the fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Annals of Ulster, of Somairle's forces being drawn from Argyll, Kintyre, Dublin, and the Isles, reveals the climax of Somairle's authority and further confirms his usurpation of power from Guðrøðr.[132] Despite the record preserved by the Icelandic annals—that Guðrøðr regained the kingship of the Isles in 1160—it appears that Guðrøðr made his actual return to the region after Somairle's fall.[133] Although it is possible that Dubgall was able to secure power following his father's demise,[134] it is evident from the Chronicle of Mann that the kingship was seized by Guðrøðr's brother, Rǫgnvaldr, before the end of the year.[135] Almost immediately afterwards, Guðrøðr is said by the same source to have arrived on Mann, ruthlessly overpowered his brother, having him mutilated and blinded.[136] Guðrøðr thereafter regained the kingship,[137] and the realm was divided between the Crovan dynasty and the Meic Somairle,[138] in a partitioning that stemmed from Somairle's strike against Guðrøðr in 1156.[139][note 8]

In an entry dated 1172, the chronicle states that Mann was invaded by a certain Ragnall mac Echmarcacha, a man who slaughtered a force of Manx coast-watchers before being slain himself in a later engagement on the island. Although the chronicle claims that Ragnall was of "royal stock",

Another possibility is that Ragnall's attack was somehow related to events in northern Ireland, where the Meic Lochlainn lost hold of the Cenél nEógan kingship to

King of Dublin

For a brief duration of his career, Guðrøðr appears to have possessed the kingship of Dublin. The chronology of his rule is unclear, however, as surviving sources concerning this episode are somewhat contradictory.[157] According to the Chronicle of Mann, the Dubliners invited Guðrøðr to rule over them as king in the third year of his reign in the Isles.[158] If correct, such an arrangement would have almost certainly provoked Muirchertach, the Dubliners' Irish overlord.[159][note 11] In fact, the chronicle reveals that Muirchertach indeed took exception to such overtures, and marched on Dublin with a massive host before forming up at "Cortcelis". Whilst in control of Dublin, Guðrøðr and the defending Dubliners are stated to have repulsed a force of three thousand horsemen under the command of a certain Osiblen. After the latter's fall, Muirchertach and his remaining host retired from the region.[158]

The chronicle's version of events appears to be corroborated by the Annals of Ulster. Unlike the previous source, however, this one dates the episode to 1162. Specifically, Muirchertach's forces are recorded to have devastated the Ostman lands of "Magh Fitharta" before his host of horsemen were repulsed.

In the winter of 1176/1177, the chronicle reveals that Guðrøðr was formally married to Muirchertach's granddaughter, Findguala Nic Lochlainn, in a ceremony conducted under the auspices of the visiting

There may be reason to suspect that Guðrøðr's defeat to Somairle was partly enabled by an alliance between Muirchertach and Somairle.

Opposed to the English in Ireland

Later in his reign, Guðrøðr again involved himself in the affairs of Dublin.

According to the twelfth-century

The successive deaths of Diarmait and Ascall left a power vacuum in Dublin that others sought to fill. Almost immediately after Ascall's fall, for example, Ruaidrí had the English-controlled town besieged.

Aligned with the English in Ireland

According to the Chronicle of Northampton, Guðrøðr attended the coronation of Henry II's teenage son,

In 1177, John led an invasion of Ulaid (an area roughly encompassing what is today

Although the promise of maritime military support could well have motivated John to align himself with Guðrøðr,

Ecclesiastical activities

There is reason to regard Óláfr, like his Scottish counterpart David, as a reforming monarch.

The ecclesiastical jurisdiction within Guðrøðr's kingdom was the

It may have been in the context of this ecclesiastical crisis in the Isles that Guðrøðr undertook his journey to Norway in 1152. Guðrøðr's overseas objective, therefore, may have been to secure the patronage of a Scandinavian

Despite the ecclesiastical reorientation, the next Bishop of the Isles known from Manx sources was consecrated by

The next known bishop was Reginald, a Norwegian who witnessed the bitter struggles between Guðrøðr and Somairle, and who seems to have died in about 1170.

Death and descendants

According to the Chronicle of Mann, Guðrøðr had four children: Affrica, Rǫgnvaldr, Ívarr, and

Many anecdotes about him worthy of being remembered could be told, which for brevity's sake we have omitted.

— a less-than-illuminative excerpt from the Chronicle of Mann concerning Guðrøðr.[293]

Guðrøðr died on 10 November 1187 on St Patrick's Isle.[294] The fact that Guðrøðr and his son, Óláfr svarti, are recorded to have died on this islet could indicate that it was a royal residence.[295][note 23] In any case, the following year Guðrøðr was finally laid to rest on Iona,[130] an island upon which the oldest intact building is St Oran's Chapel.[298] Certain Irish influences in this building's architecture indicate that it dates to about the mid twelfth century.[299] The chapel could well have been erected by Óláfr or Guðrøðr.[129][note 24] Certainly, their family's remarkable ecclesiastical activities during this period suggest that patronage of Iona is probable.[300]

Upon Guðrøðr's death the chronicle claims that he left instructions for his younger son, Óláfr svarti, to succeed to the kingship since he had been born "in lawful wedlock".

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Guðrøðr Óláfsson | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- patronyms in English secondary sources: Godfrey mac Aulay,[19] Godhfhraidh mac Amhlaoibh,[3] Godred Olafsson,[20] Godred Óláfsson,[21] Gofhraidh mac Amhlaíbh,[6] Gofraid Mac Amlaíb,[22] Gofraid mac Amlaíb,[23] Gofraidh mac Amhlaoibh,[24] Guðrøð Óláfsson,[12] Guðrǫðr Óláfsson,[13] Guðröðr Óláfsson,[25] Guðrøðr Óláfsson,[26] and Guðrøðr Ólafsson.[27] Guðrøðr has also been accorded an epithet: Godred the Black.[28]

- Robert de Torigni, Abbot of Mont Saint-Michel.[34] Henry II's mother was Matilda, daughter of Henry I.[35] The Chronica notes that Guðrøðr and Henry II were related by blood through Matilda, stating in Latin: "Est enim prædictus rex consanguineus regis Anglorum ex parte Matildis imperatricis matris suæ" ("For the aforesaid king is the cousin of the English king on the side of Matilda the empress, his mother").[34]

- ^ According to the chronicle, Haraldr had been castrated by at some point in the late 1090s. If correct, it would seem that the Haraldssonar were at least in their fifties when they confronted their uncle,[60] a man who must have been at least in his late fifties.[61]

- ^ The inscription of the vessel may date to about the time of the Crovan dynasty, possibly from about the eleventh- to the thirteenth century.[71] The vessel appears to be similar to those that appear on seals borne by members of the dynasty.[73] Members of the dynasty known to have borne seals include: Guðrøðr himself,[74] (Guðrøðr's son) Rǫgnvaldr,[75] and (Óláfr svarti's son) Haraldr.[76] Evidence of Guðrøðr's seal stems from his 1154 charter of confirmation to Furness, which states: "in order that this licence... may be firmly observed in my kingdom, I have strengthened it by the authority of my seal affixed to the present charter".[77] No seal used by a member of the dynasty survives today.[78]

- Gall Gaidheil of Arran, Kintyre, Mann, and the territory of Scotland.[83]

- ^ The chronicle dates the battle to the year 1156. Since the start of a new year in the Julian calendar is 25 March, the year of the battle in the Gregorian calendar is 1157.[93] Whatever the year, the weather conditions must have been particularly good to permit a naval battle at this time of season.[94]

- ^ The next secular witness listed after Guðrøðr is Fergus' son, Uhtred. Whether the latter was there in defiance of his father—or as a representative of him—is unknown. It is possible that discussion regarding Guðrøðr's plight was one of the factors in Uhtred's attestation.[110]

- ^ At one point, after noting this 1156 segmentation, the chronicle laments the "downfall" of the Kingdom of the Isles from the time Somairle's sons "took possession of it".[140] One possibility is that this statement is evidence that members of the Meic Somairle held a share of the kingdom before their father's demise.[141] It could even be evidence that it was not Somairle who had possessed the partition, but his sons.[142]

- ^ The stone is carved in a Scandinavian style.[145] It is similar to other Manx[146] and Anglo-Scandinavian sculpted stones.[147] It may date to the tenth- or eleventh century.[148]

- ^ Ascall was a member of the Meic Torcaill.[153] If Ragnall was indeed a member of this family, his name could indicate that he was a son of Echmarcach Mac Torcaill,[152] a man who—along with his brother Aralt—witnessed a charter of Diarmait between 1162 and 1166.[154]

- ^ Following Muirchertach's defeat of Toirrdelbach in 1154, and the former's march on Dublin, the Annals of the Four Masters reports that the Dubliners rendered Muirchertach the kingship and gave him one thousand, two hundred cattle.[160]

- Ottar mac meic Ottair, King of Dublin, an Islesmen who had attained the kingship of Dublin in 1142.[182] This act may well have represented a threat to the authority of Guðrøðr's father, and the prospects of Guðrøðr himself.[183] Certainly, the kin-slaying Haraldssonar who slew Óláfr a decade after Ottar's accession were raised in Dublin. Enmity between Þorfinnr and Guðrøðr, therefore, could have been a continuation of hostilities between their respective families.[181]

- ^ Orkney is located in a chain of islands known as the Northern Isles. In Old Norse, these islands were known as Norðreyjar, as opposed to the Isles (the Hebrides and Mann) which were known as Suðreyjar ("Southern Islands").[195]

- ^ According to the Chronicle of Mann, Óláfr svarti was three years old at the time of his parents' marriage in 1176/1177. As such, one possibility is that the liaison between Guðrøðr and Findguala commenced at about the time of siege.[204]

- ^ The marriage is dated to 1180 by the unreliable eighteenth-century Dublin Annals of Inisfallen.[218] Much of the information presented by this source appears to be derived from Expugnatio Hibernica, and it is possible that this is the origin of the marriage-date as well.[219]

- ^ The pictured piece depicts a seated bishop, holding a crozier with two hands, and wearing a chasuble as an outer garment. The simple horned mitre worn by this particular piece may be evidence that it dates to the mid twelfth century, when horns began to be positioned on the front and back, as opposed to the sides of the headdress.[242]

- ^ The diocese is generally called Sodorensis in mediaeval sources.[244] This Latin term is derived from the Old Norse Suðreyjar,[245] and therefore means "of the Southern Isles", in reference to Mann and the Hebrides as opposed to the Northern Isles.[246]

- Haraldr gilli, King of Norway and Bjaðǫk, a woman who seems to have borne a Gaelic name. Eysteinn was eventually recognised as Haraldr gilli's son, and it is conceivable that Eysteinn and Bjaðǫk had powerful relatives who backed their claims. In regard to Guðrøðr, it is possible that his cooperation with Ingi was undertaken in the context of avoiding having to deal with Eysteinn and his seemingly Irish or Hebridean kin.[261]

- ^ Today Niðaróss is known as Trondheim.[264] Of the eleven dioceses, five were centred in Norway and six in colonies overseas (two in Iceland, one in Orkney, one in the Faroe Islands, one in Greenland, and one in the Isles).[262]

- ^ The fact the poem also describes Rǫgnvaldr as a descendant of "Lochlann of the ships", Conn, and Cormac,—all apparent members of the Uí Néill—could indicate that Guðrøðr's apparent marriage to Sadb represents an earlier alliance with Muirchertach.[169]

- ^ It is possible that seat of Manx royal power was located at Peel Castle before the seat moved to Castle Rushen in the thirteenth century.[296] The earliest evidence of ecclesiastical structures on the islet date to the tenth- and eleventh centuries.[297]

- ^ Other potential candidates include Somairle and his son, Ragnall.[128]

Citations

- ^ Dimock (1867) p. 265; Royal MS 13 B VIII (n.d.).

- ^ Coira (2012); Stephenson (2008); Barrow (2006); Boardman (2006); Brown (2004); Bartlett (1999); McDonald (1997); McDonald (1995).

- ^ a b Coira (2012).

- ^ McDonald (2019); Crawford, BE (2014); Sigurðsson; Bolton (2014); Wadden (2014); Downham (2013); Kostick (2013); MacDonald (2013); Flanagan (2010); Jamroziak (2008); Martin (2008); Abrams (2007); McDonald (2007a); Davey, PJ (2006a); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); Hudson (2005); McNamee (2005); Pollock (2005); Duffy (2004a); Duffy (2004b); Duffy (2004d); Sellar (2004); Woolf (2003); Beuermann (2002); Davey, P (2002); Freke (2002); Jennings, AP (2001); Oram (2000); Watt (2000); Thornton (1996); Watt (1994); Oram (1993); McDonald; McLean (1992); Freke (1990); Oram (1988); Power (1986); Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.).

- ^ Rubin (2014).

- ^ a b McLeod (2002).

- ^ Ní Mhaonaigh (2018); Veach (2014); McDonald (2007a); Woolf (2005); Woolf (2004); Duffy (2004b); Woolf (2001); Duffy (1999); Thornton (1996); Duffy (1995); Duffy (1993); Duffy (1992); Duffy (1991).

- ^ Duffy (2007); McDonald (2007a).

- ^ McDonald (2007a); Purcell (2003–2004).

- ^ Flanagan (1977).

- ^ Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.).

- ^ a b Williams, DGE (1997).

- ^ a b Sigurðsson; Bolton (2014).

- ^ Beuermann (2014); Williams, G (2007).

- ^ Ekrem; Mortensen; Fisher (2006).

- ^ Duffy (2005a).

- ^ Veach (2018); Caldwell (2016); McDonald (2016); Rubin (2014); Veach (2014); Downham (2013); MacDonald (2013); Oram (2013); McDonald (2012); Oram (2011); Beuermann (2010); Beuermann (2009); Beuermann (2008); McDonald (2008); Duffy (2007); McDonald (2007a); McDonald (2007b); Woolf (2007); Duffy (2006); Macniven (2006); Power (2005); Salvucci (2005); Duffy (2004b); Thornton (1996); Gade (1994).

- ^ Duffy (2004b); Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.).

- ^ Boardman (2006).

- ^ McDonald (2019); Crawford, BE (2014); Sigurðsson; Bolton (2014); Abrams (2007); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); Hudson (2005); McNamee (2005); Woolf (2003); Beuermann (2002); Jennings, AP (2001); Oram (2000).

- ^ Oram (2000).

- ^ Duffy (1995).

- ^ Ní Mhaonaigh (2018); Veach (2014); Woolf (2005); Duffy (1993); Duffy (1992).

- ^ Duffy (2007); Ó Mainnín (1999).

- ^ Beuermann (2014).

- ^ Caldwell (2016); McDonald (2016); Rubin (2014); Veach (2014); Downham (2013); Oram (2013); McDonald (2012); Beuermann (2010); McDonald (2008); Duffy (2007); McDonald (2007a); McDonald (2007b); Woolf (2007); Duffy (2004b); Gade (1994); Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.).

- ^ Oram (2011); Macniven (2006).

- ^ Kostick (2013).

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; Oram (2011) pp. xv tab. 4, xvi tab. 5; McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1; Williams, G (2007) p. 141 ill. 14; Power (2005) p. 34 tab.; Brown (2004) p. 77 tab. 4.1; Sellar (2000) p. 192 tab. i; McDonald (1997) p. 259 tab.; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 200 tab. ii; Anderson (1922) p. 467 n. 2 tab.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; Oram (2011) pp. xv tab. 4, xvi tab. 5; McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1; Williams, G (2007) p. 141 ill. 14; Sellar (2000) p. 192 tab. i.

- ^ a b McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1.

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 342; Wadden (2014) pp. 31–32; McDonald (2012) p. 157; McDonald (2007b) pp. 66, 75, 154; Anderson (1922) p. 137; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 60–61.

- ^ Oram (1988) pp. 71–72, 79.

- ^ a b Oram (2000) p. 60; Oram (1993) p. 116; Oram (1988) pp. 72, 79; Anderson (1908) p. 245; Lawrie (1910) p. 115 § 6; Howlett (1889) pp. 228–229.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. xiii tab. 2.

- ^ Oram (1988) p. 79.

- ^ Oram (1993) p. 116; Oram (1988) p. 79.

- ^ Oram (1993) p. 116; Oram (1988) p. 80.

- ^ Oram (1988) p. 80.

- ^ Munch; Goss (1874) p. 62; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- ^ Oram (2011) pp. 86–89.

- ^ Beuermann (2012) p. 5; Beuermann (2010) p. 102; Williams, G (2007) p. 145; Woolf (2005); Brown (2004) p. 70; Rixson (2001) p. 85.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. viii, 59, 62–63, 93; Wadden (2014) p. 32; McDonald (2007b) pp. 67, 116; McDonald (1997) p. 60; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Anderson (1922) p. 137; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 60–61.

- ^ Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 156 fig. 1b, 163 fig. 8e.

- ^ Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) p. 198.

- ^ McDonald (2012) pp. 168–169, 182 n. 175; Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 165, 197.

- ^ Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 155, 168–173.

- ^ McDonald (2012) p. 182 n. 175; Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) p. 178.

- ^ Beuermann (2014) p. 85; Oram (2011) p. 113; Oram (2000) p. 73; Anderson (1922) p. 137; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 60–61.

- ^ Oram (2000) p. 73.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 113; Oram (2000) p. 73.

- ^ Beuermann (2014) p. 93 n. 43; Oram (2011) p. 113.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 113; Beuermann (2002) pp. 421–422; Oram (2000) p. 73.

- ^ Rubin (2014) ch. 4 ¶ 18; Downham (2013) p. 172; McDonald (2012) p. 162; Oram (2011) p. 113; Beuermann (2010) pp. 106–107; Ekrem; Mortensen; Fisher (2006) p. 165; Hudson (2005) p. 198; Power (2005) p. 22; Beuermann (2002) p. 419, 419 n. 2; Jennings, AP (2001); Oram (2000) p. 73; Anderson (1922) p. 225; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 62–63.

- ^ Crawford, BE (2014) pp. 70–72; Hudson (2005) p. 198; Johnsen (1969) p. 20; Anderson (1908) p. 245; Lawrie (1910) p. 115 § 6; Howlett (1889) pp. 228–229.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 108.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 113; McDonald (2007b) p. 67; Duffy (2004b).

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 65, 74; Beuermann (2014) p. 85; Downham (2013) p. 171, 171 n. 84; Duffy (2006) p. 65; Sellar (2000) p. 191; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 259; Duffy (1993) pp. 41–42, 42 n. 59; Duffy (1991) p. 60; Oram (1988) pp. 80–81; Anderson (1922) p. 225; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 62–65.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 74; McDonald (2007b) p. 92.

- ^ Beuermann (2002) p. 423.

- ^ Beuermann (2002) p. 423 n. 26.

- ^ Clancy (2008) p. 36; Davey, P (2002) p. 95; Duffy (1993) p. 42; Oram (1988) p. 81; Anderson (1922) pp. 225–226; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b Oram (1988) p. 81.

- ^ a b McDonald (2019) p. 65; Crawford, BE (2014) p. 74; Downham (2013) p. 171; McDonald (2012) p. 162; Oram (2011) p. 113; Abrams (2007) p. 182; McDonald (2007a) p. 66; McDonald (2007b) pp. 67, 85; Duffy (2006) p. 65; Oram (2000) pp. 69–70; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 259; Gade (1994) p. 199; Duffy (1993) p. 42; Oram (1988) p. 81; Anderson (1922) p. 226; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 64–67.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) pp. 27 tab. 1, 58, 67, 85.

- ^ McDonald (2007a) p. 51; Duffy (2007) p. 3; Thornton (1996) p. 95; Duffy (1993) p. 42; Duffy (1992) p. 126.

- ^ Oram (1988) pp. 81, 85–86; Powicke (1978) pp. 45–46.

- ^ Oram (2011) pp. 81–82, 113.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 113.

- ^ McDonald (2007a) p. 59; McDonald (2007b) pp. 128–129 pl. 1; Rixson (1982) pp. 114–115 pl. 1; Cubbon (1952) p. 70 fig. 24; Kermode (1915–1916) p. 57 fig. 9.

- ^ a b McDonald (2012) p. 151; McDonald (2007a) pp. 58–59; McDonald (2007b) pp. 54–55, 128–129 pl. 1; Wilson, DM (1973) p. 15.

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 337; McDonald (2012) p. 151; McDonald (2007b) pp. 120, 128–129 pl. 1.

- ^ McDonald (2007a) pp. 58–60; McDonald (2007b) pp. 54–55; Wilson, DM (1973) p. 15, 15 n. 43.

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 343; McDonald (2007b) p. 204.

- ^ McDonald (2016) pp. 341, 343–344; McDonald (2007b) pp. 56, 79, 204–205, 216, 221; McDonald (1995) p. 131; Rixson (1982) p. 127.

- ^ McDonald (2016) pp. 341, 343; McDonald (2007a) pp. 59–60; McDonald (2007b) pp. 55–56, 128–129 pl. 2, 162, 204–205; McDonald (1995) p. 131; Rixson (1982) pp. 127–128, 146.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 204; Brownbill (1919) pp. 710–711 § 4; Oliver (1861) pp. 13–14; Document 1/14/1 (n.d.).

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 344.

- ^ Duffy (2007) p. 2; O'Byrne (2005a); O'Byrne (2005c); Pollock (2005) p. 14; Duffy (2004c).

- ^ Wadden (2014) pp. 29–31; Oram (2011) pp. 113, 120; McDonald (2008) p. 134; Duffy (2007) p. 2; McDonald (2007a) p. 71; O'Byrne (2005a); O'Byrne (2005b); O'Byrne (2005c); Duffy (2004c); Griffin (2002) pp. 41–42; Oram (2000) p. 73; Duffy (1993) pp. 42–43; Duffy (1992) pp. 124–125.

- ^ Wadden (2014) pp. 18, 29–30, 30 n. 78; Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 1154.11; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 1154.11; Oram (2011) pp. 113, 120; Clancy (2008) p. 34; McDonald (2008) p. 134; Butter (2007) p. 141, 141 n. 121; Duffy (2007) p. 2; McDonald (2007a) p. 71; Pollock (2005) p. 14; Oram (2000) p. 73; Simms (2000) p. 12; Duffy (1992) pp. 124–125.

- ^ Wadden (2014) pp. 30–31; Oram (2011) pp. 113, 120; McDonald (2008) p. 134; Duffy (2007) p. 2; McDonald (2007a) p. 71; McDonald (2007b) p. 118.

- ^ Clancy (2008) p. 34.

- ^ Griffin (2002) p. 42.

- ^ Wadden (2014) p. 34; O'Byrne (2005a); Duffy (2004c); Griffin (2002) p. 42.

- ^ French (2015) p. 23; Duffy (2004c).

- ^ Stevenson (1841) p. 4; Cotton MS Domitian A VII (n.d.).

- ^ Oram (2011) pp. 113–114, 120.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 47; Wadden (2014) p. 32; Downham (2013) p. 172; Woolf (2013) pp. 3–4; Oram (2011) p. 120; Williams, G (2007) pp. 143, 145–146; Woolf (2007) p. 80; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 243–244; Woolf (2004) p. 104; Rixson (2001) p. 85; Oram (2000) pp. 74, 76; McDonald (1997) pp. 52, 54–58; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 259–260, 260 n. 114; Duffy (1993) pp. 40–41; McDonald; McLean (1992) pp. 8–9, 12; Scott (1988) p. 40; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) p. 231; Lawrie (1910) p. 20 § 13; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- ^ McDonald (1997) p. 58; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) p. 231; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- ^ Jónsson (1916) p. 222 ch. 11; AM 47 Fol (n.d.).

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 32, 74; Caldwell (2016) p. 354; McDonald (2012) pp. 153, 161; Oram (2011) p. 120; McDonald (2007a) pp. 57, 64; McDonald (2007b) p. 92; Barrow (2006) pp. 143–144; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 244; Woolf (2004) p. 104; Oram (2000) p. 76; McDonald (1997) pp. 52, 56; Duffy (1993) p. 43; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Scott (1988) p. 40; Rixson (1982) pp. 86–87; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) pp. 231–232; Lawrie (1910) p. 20 § 13; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- ^ Oram (2000) p. 85 n. 127.

- ^ McDonald (1997) p. 56 n. 48.

- ^ McDonald (1997) p. 56.

- ^ McDonald (2012) pp. 153, 161; Oram (2011) p. 121; McDonald (2007a) pp. 57, 64; McDonald (2007b) pp. 92, 113, 121 n. 86; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 244; Woolf (2004) p. 104; Oram (2000) p. 76; McDonald (1997) p. 56; Duffy (1993) p. 43; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Rixson (1982) pp. 86–87, 151; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) p. 239; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- ^ McDonald (2012) pp. 159–161.

- ^ a b McDonald (1997) p. 57.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 121.

- ^ McDonald (1997) p. 57; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196.

- ^ Oram (2000) p. 76; McDonald (1997) p. 57.

- ^ Liber S. Marie de Calchou (1846) pp. III–VII; Diplomatarium Norvegicum (n.d.) vol. 19 § 38; Document 1/5/24 (n.d.).

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 341; Oram (2011) p. 12; Stephenson (2008) p. 12; McDonald (2007b) p. 113; Oram (2000) p. 76; Johnsen (1969) p. 22; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5; Anderson (1922) p. 246 n. 4; Bain (1881) p. 9 §§ 56, 60; Hunter (1844) pp. 155, 168; Diplomatarium Norvegicum (n.d.) vol. 19 § 35.

- ^ a b Oram (2000) p. 76.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 121; Oram (2000) pp. 76–77.

- ^ Taylor (2016) p. 250; Oram (2011) p. 121; Beuermann (2008); McDonald (2007a) p. 57; McDonald (2007b) p. 113; Power (2005) p. 24; Oram (2000) p. 77; Barrow (1995) pp. 11–12; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 12 n. 5; Johnsen (1969) p. 22; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5; Liber S. Marie de Calchou (1846) pp. III–VII; Diplomatarium Norvegicum (n.d.) vol. 19 § 38; Document 1/5/24 (n.d.).

- ^ Beuermann (2009); Beuermann (2008); McDonald (2007b) p. 113.

- ^ a b Oram (2011) pp. 121–122.

- ^ Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 60–61; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- ^ Oram (2000) pp. 79–80.

- ^ Oram (2011) pp. 118–122; Oram (2000) p. 80; Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 136–137, 136 n. 1, 189; Anderson (1922) p. 245.

- ^ Oram (2011) pp. 118–122.

- ^ Oram (2011) pp. 118–119; Oram (2000) p. 80.

- ^ MacInnes (2019) p. 135; MacDonald (2013) p. 30 n. 51; Woolf (2013) p. 5; Oram (2011) pp. 118–119; Beuermann (2008); McDonald (2007b) p. 113; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245; Oram (2000) p. 81; Barrow (1994).

- ^ Woolf (2013) p. 5.

- ^ Woolf (2013) pp. 5–6; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245.

- ^ Storm (1899) p. 629.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 121; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 244–245; Oram (2000) p. 77; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 111.

- ^ a b c Finlay; Faulkes (2015) pp. 228–229 ch. 17; McDonald (2012) p. 162; Hollander (2011) p. 784 ch. 17; Beuermann (2010) p. 112, 112 n. 43; McDonald (2007b) p. 113; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245; Power (2005) p. 24; Salvucci (2005) p. 182; Beuermann (2002) pp. 420–421 n. 8; Oram (2000) p. 77; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5; Anderson (1922) pp. 248–249; Jónsson (1911) pp. 609–610 ch. 17; Storm (1899) pp. 629–630 ch. 17; Unger (1868) pp. 772–773 ch. 17; Laing (1844) pp. 293–294 ch. 17.

- ^ Storm (1977) pp. 116 § iv, 322 § viii, 475 § x; Johnsen (1969) p. 22; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5; Anderson (1922) p. 246; Vigfusson (1878) p. 360; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 516.

- ^ a b Beuermann (2010) p. 112.

- ^ Antonsson; Crumplin; Conti (2007) p. 202.

- ^ Ghosh (2011) p. 206.

- ^ Ghosh (2011) p. 206; Beuermann (2010) p. 112.

- ^ Beuermann (2002) p. 421 n. 10.

- ^ McDonald (2012) p. 156; Power (2005) p. 28; McDonald (1997) p. 246; Ritchie (1997) p. 101.

- ^ McDonald (2012) p. 156; Power (2005) p. 28; McDonald (1997) p. 246; Ritchie (1997) pp. 100–101; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) pp. 245 § 12, 249–250 § 12.

- ^ a b McDonald (2012) p. 156; Bridgland (2004) p. 89; McDonald (1997) pp. 62, 246; Ritchie (1997) pp. 100–101; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 250 § 12.

- ^ a b McDonald (2012) p. 156; Power (2013) p. 66; Power (2005) p. 28.

- ^ a b McDonald (2016) p. 343; Beuermann (2014) p. 91; Power (2013) p. 66; McDonald (2012) pp. 153, 155; McDonald (2007b) p. 70, 201; Power (2005) p. 28; Duffy (2004b).

- ^ Jennings, A (2017) p. 121; Oram (2011) p. 128; McDonald (2007a) p. 57; McDonald (2007b) pp. 54, 67–68, 85, 111–113; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) p. 189; Duffy (1999) p. 356; McDonald (1997) pp. 61–62; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150; Duffy (1993) p. 31; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1164.4; Oram (2011) p. 128; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1164.4; Oram (2000) p. 76; Duffy (1999) p. 356; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Anderson (1922) pp. 253–254.

- ^ Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 128.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 46, 48; Oram (2011) pp. 128–129; McDonald (2007b) pp. 67–68, 85; Anderson (1922) pp. 258–259; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 74–75.

- ^ Oram (2011) pp. 128–129; McDonald (2007a) p. 57; McDonald (2007b) pp. 67–68, 85; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150; Anderson (1922) pp. 258–259; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 74–75.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 85; Duffy (2004b).

- ^ Sellar (2004); McDonald (1997) pp. 70–71; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150.

- ^ McDonald (1997) pp. 70–71; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 150, 260.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. viii, 32; Coira (2012) pp. 57–58 n. 18; McDonald (1997) p. 60; Duffy (1993) p. 43; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Anderson (1922) p. 232; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- ^ McDonald (1997) p. 60; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197.

- ^ Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197.

- ^ Mac Lean (1985a) pp. 439–440; Mac Lean (1985b) pls. 88a–88b; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 212 § 95 figs. a–b; Reports of District Secretaries (1903) p. 305 fig.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 70; Mac Lean (1985a) p. 440; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) pp. 212–213 § 95; Kermode (1915–1916) p. 61; Reports of District Secretaries (1903) p. 306.

- ^ Mac Lean (1985a) pp. 439–440; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) pp. 212–213 § 95.

- ^ McDonald (2012) p. 155; McDonald (2007b) p. 70; Mac Lean (1985a) p. 439.

- ^ Mac Lean (1985a) pp. 439–440; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 21.

- ^ Mac Lean (1985a) p. 440; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 21.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 46, 48; McDonald (2007b) pp. 85–86, 85 n. 88; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150; Duffy (1993) p. 61, 61 n. 69; Anderson (1922) p. 305; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 76–79.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) pp. 85–86.

- ^ Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 150, 260–261, 260 n. 121.

- ^ a b c Duffy (1993) p. 61.

- ^ Downham (2013) p. 178 tab.

- ^ Duffy (1993) pp. 45, 61; Duffy (1992) pp. 128–129; Butler (1845) pp. 50–51 § 69.

- ^ a b Oram (2000) p. 105.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 85 n. 88; Duffy (1993) p. 61, 61 n. 69.

- ^ a b Duffy (2007) pp. 3–4; Oram (2000) pp. 74–75; Duffy (1993) p. 44; Duffy (1992) pp. 126–128.

- ^ a b Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) pp. 145–146; Downham (2013) pp. 166, 171–172; McDonald (2008) p. 134; Duffy (2007) p. 3; McDonald (2007a) p. 52; Oram (2000) pp. 74–75; Duffy (1993) pp. 43–45; Duffy (1992) pp. 126–127; Duffy (1991) p. 67; Anderson (1922) p. 230–231; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 66–69.

- ^ Oram (2000) p. 75; Duffy (1992) p. 126.

- ^ Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) §§ 1154.12, 1154.13; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) §§ 1154.12, 1154.13; Duffy (1993) p. 42.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1162.4; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1162.4; Duffy (2007) pp. 3–4; Oram (2000) p. 75; Duffy (1993) p. 44; Duffy (1992) p. 128.

- ^ Duffy (1993) p. 44; Duffy (1992) p. 128.

- ^ Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 1162.11; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 1162.11; Duffy (2007) p. 4; Oram (2000) p. 75; Duffy (1993) p. 44; Duffy (1992) p. 128.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1162.5; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1162.5; Duffy (1993) p. 45.

- ^ Duffy (2007) p. 4; Duffy (1993) pp. 44–45; Duffy (1992) p. 128.

- ^ Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) p. 157 fig. 2a, 163 fig. 8d, 187 fig. 14.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 64; McDonald (2016) p. 342; Beuermann (2014) p. 93, 93 n. 45; Wadden (2014) pp. 32–33; Downham (2013) p. 172, 172 n. 86; Flanagan (2010) p. 195, 195 n. 123; Duffy (2007) p. 4; McDonald (2007a) p. 52; McDonald (2007b) pp. 68, 71, 171, 185; Oram (2000) p. 109 n. 24; Watt (2000) p. 24; McDonald (1997) pp. 215–216; Duffy (1993) p. 58; Duffy (1992) p. 127 n. 166; Flanagan (1989) p. 103; Power (1986) p. 130; Flanagan (1977) p. 59; Anderson (1922) pp. 296–297; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 76–77; Haddan; Stubbs (1873) p. 247.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 60; Flanagan (2010) p. 195; McDonald (2007a) p. 52; McDonald (2007b) p. 71; Martin (2008) p. 135; Pollock (2005) p. 16 n. 76; Flanagan (1989) p. 103; Anderson (1922) p. 297 n. 1.

- ^ a b Wadden (2014) p. 33.

- ^ Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) p. 146; Duffy (1992) p. 128 n. 166.

- ^ Pollock (2005) p. 16 n. 76.

- ^ Downham (2013) p. 172; Duffy (2007) p. 4.

- ^ Oram (2000) pp. 74–75.

- ^ Oram (2011) pp. 113–114, 120; Oram (2000) pp. 74–76.

- ^ Oram (2000) p. 75; McDonald (1997) pp. 55–56.

- ^ Duffy (2007) pp. 2–3; Pollock (2005) p. 14, 14 n. 69; Oram (2000) p. 75; Duffy (1999) p. 356; Duffy (1993) pp. 31, 42–43.

- ^ Duffy (2007) p. 3; McDonald (1997) pp. 55–56; Duffy (1993) p. 43.

- ^ McDonald (1997) pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b Oram (2011) p. 128; Oram (2000) p. 76.

- ^ Williams, G (2007).

- ^ a b Downham (2013) pp. 171–172.

- ^ Downham (2013) pp. 171–172; Oram (2000) pp. 67, 76; Duffy (1993) pp. 40–41; Duffy (1992) pp. 121–122.

- ^ Downham (2013) pp. 171–172; Oram (2000) p. 67.

- ^ French (2015) p. 27; Simms (1998) p. 56.

- ^ McDonald (2008) p. 134; Duffy (2007) p. 6; Duffy (2004b).

- ^ Flanagan (2004b); Flanagan (2004c).

- ^ Duffy (2007) pp. 4–5.

- ^ Crooks (2005a); Flanagan (2004b).

- ^ Flanagan (2004a); Flanagan (2004b); Duffy (1998) pp. 78–79; Duffy (1992) p. 131.

- ^ Flanagan (2004a); Duffy (1998) pp. 78–79.

- ^ Duffy (1998) p. 79; Duffy (1992) pp. 131–132.

- ^ Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 161 fig. 6c, 184 fig. 11, 189 fig. 16.

- ^ Downham (2013) p. 157 n. 1; McDonald (2008) p. 135; Duffy (2007) p. 5; Duffy (2005b) p. 96; Purcell (2003–2004) p. 285; Duffy (1998) p. 79; Duffy (1993) pp. 46, 60; Duffy (1992) p. 132; Wright; Forester; Hoare (1905) pp. 213–215 (§ 17); Dimock (1867) pp. 256–258 (§ 17).

- ^ Downham (2013) p. 157 n. 1.

- ^ McDonald (2012) p. 152.

- ^ Duffy (2005b) p. 96; Duffy (1998) p. 79; Duffy (1992) p. 132, 132 n. 184.

- ^ Duffy (1992) p. 132, 132 n. 184.

- ^ Duffy (2007) p. 5; Duffy (1992) p. 132.

- ^ Song of Dermot and the Earl (2011) pp. 165, 167 (§§ 2257–2272); McDonald (2008) pp. 135–136, 135–136 n. 24; Duffy (2007) p. 5; Song of Dermot and the Earl (2010) pp. 164, 166 (§§ 2257–2272); Duffy (1992) p. 132; Wright; Forester; Hoare (1905) pp. 219–221 (§ 21); Dimock (1867) pp. 263–265 (§ 21).

- ^ Duffy (2007) pp. 5–6; Purcell (2003–2004) p. 287; Duffy (1992) p. 132.

- ^ McDonald (2012) p. 160; Barrett (2004).

- ^ O'Byrne (2005) p. 469; Duffy (1992) p. 132.

- ^ a b Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) pp. 145–146, 146 n. 80; Wyatt (2018) p. 797; Wyatt (2009) p. 391; McDonald (2008) pp. 134, 136; Duffy (2007) p. 6; McDonald (2007a) pp. 52, 63, 70; Pollock (2005) p. 15; Power (2005) p. 37; Purcell (2003–2004) p. 288, 288 n. 59; Gillingham (2000) p. 94; Duffy (1993) pp. 46–47, 59–60; Duffy (1992) pp. 132–133; Duffy (1991) p. 60; Wright; Forester; Hoare (1905) pp. 221–222 (§ 22); Dimock (1867) pp. 265–266 (§ 22).

- ^ Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) p. 146; Anderson (1922) pp. 296–297; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b Kostick (2013) ch. 6 ¶ 88.

- ^ Duffy (2007) p. 7; O'Byrne (2005) p. 469; Duffy (1993) p. 47; Duffy (1992) p. 133.

- ^ Downham (2013) p. 157.

- ^ Duffy (2005b) p. 96; Flanagan (2004a); Simms (1998) p. 57.

- ^ Strickland (2016) pp. 86, 357 n. 61.

- ^ Strickland (2016) p. 86.

- ^ Strickland (2016) p. 357 n. 61.

- ^ McDonald (2008) pp. 135–136; McDonald (2007a) p. 52; McDonald (2007b) pp. 124–125; Duffy (1992) p. 133; Duffy (1991) p. 60.

- ^ McDonald (2008) p. 136; McDonald (2007b) p. 125.

- ^ Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) pp. 145–146; Veach (2018) p. 167; McDonald (2008) p. 136; McDonald (2007b) p. 125; Duffy (2005a); Duffy (2004a); Oram (2000) p. 105; Power (1986) p. 130.

- ^ McDonald (2008) pp. 136–137; Crooks (2005b); Duffy (2005a); Duffy (2004a).

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 60; McDonald (2007b) p. 126; Duffy (1995) p. 25, n. 167; Duffy (1993) p. 58.

- ^ McDonald (2008) pp. 137–138; McDonald (2007b) pp. 126–127; Duffy (1996) p. 7.

- ^ Veach (2014) pp. 56–57; McDonald (2008) p. 136; McDonald (2007b) p. 126; Duffy (2005a); Duffy (2004a); Duffy (1995) p. 25 n. 167; Duffy (1993) p. 58, 58 n. 53; Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.) p. 11 § 2.5.9.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 126; Duffy (1995) p. 25 n. 167.

- ^ McDonald (2008) p. 137; McDonald (2007b) pp. 126–127; Duffy (1995) p. 25; Duffy (1993) p. 58; Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.) pp. 10–12 §§ 2.5.8–2.5.10.

- ^ McDonald (2008) p. 137; McDonald (2007b) pp. 126–127.

- ^ Wadden (2014) p. 37, 37 n. 107; Duffy (2005a); Pollock (2005) p. 18; Oram (2000) p. 105; Duffy (1995) p. 24; Duffy (1993) p. 73; Stubbs (1871) p. 25; Riley (1853) p. 404.

- ^ Oram (2011) pp. 155–156; Pollock (2005) p. 18; Oram (2000) p. 105; Duffy (1993) pp. 72–73.

- ^ Munch; Goss (1874) p. 76; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 338; Oram (2000) p. 105; Duffy (1995) pp. 25–26; Duffy (1993) p. 58; Davies (1990) p. 52; Power (1986) p. 130.

- ^ Duffy (1995) pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) pp. 145–146; McDonald (2008) pp. 137–138; McDonald (2007b) p. 127; Duffy (1995) pp. 25–26; Duffy (1993) pp. 58–59; Duffy (1991) pp. 67–68.

- ^ Pollock (2005) p. 16.

- ^ Martin (2008) p. 135.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 127; Duffy (1991) pp. 67–68.

- ^ Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) p. 145.

- ^ Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 100–101; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- ^ McDonald (2007b) pp. 66, 192; Davey, PJ (2006a); Woolf (2001).

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 68.

- ^ Crawford, DKE (2016) p. 107; McDonald (2007b) pp. 68, 204; McIntire (1943) p. 5; Brownbill (1919) pp. 710–711 § 4; Oliver (1861) pp. 13–14; Document 1/14/1 (n.d.).

- ^ Beuermann (2014) p. 91; McDonald (2007b) pp. 68, 196; Duffy (1993) p. 57; McIntire (1943) p. 6; Wilson, J (1915) pp. 72–73 § 43; Document 1/14/2 (n.d.).

- ^ Barrow (1980) p. 158 n. 70; Wilson, J (1915) pp. 72–73 § 43, 73 n. 7; Document 1/14/2 (n.d.); Gilchrist (n.d.).

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 196.

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 343; Beuermann (2014) p. 93 n. 45; McDonald (2007b) p. 68; McDonald (1997) p. 218; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 76–77.

- ^ Jamroziak (2011) p. 82; Jamroziak (2008) pp. 32–33; McDonald (2007b) pp. 68, 196, 219; Duffy (1993) p. 57; McIntire (1943) pp. 5–6; McIntire (1941) pp. 170–171; Grainger; Collingwood (1929) pp. 94–95 § 265a; Document 1/14/3 (n.d.).

- ^ Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 157 fig. 2i, 188 fig. 15, 192 tab. 5.

- ^ Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson 2009 pp. 157 fig. 2i, 188 fig. 15, 192 tab. 5, 192–193, 197 tab. 8; Power (2005) p. 37 n. 37.

- ^ Woolf (2003) pp. 171, 180.

- ^ Davey, PJ (2008) p. 1 n. 3; Davey, PJ (2006a); Davey, PJ (2006b).

- ^ Lowe (1988) p. 33.

- ^ Beuermann (2012) pp. 4–5; Davey, PJ (2008) p. 1 n. 3; Davey, PJ (2006a); Davey, PJ (2006b).

- ^ Woolf (2003) pp. 171–172.

- ^ Beuermann (2012) pp. 4–5; Beuermann (2002) pp. 425–426.

- ^ Beuermann (2002) pp. 425–428.

- ^ Beuermann (2002) p. 428.

- ^ Beuermann (2002) pp. 428–429.

- ^ MacDonald (2013) p. 37.

- ^ Watt (2003) p. 399 map 20.1; Woolf (2003) p. 177; Barrell (2002) p. xxiv map 3.

- ^ McDonald (2012) p. 182 n. 175; Power (2005) p. 23; Beuermann (2002).

- ^ Power (2005) p. 23.

- ^ Ekrem; Mortensen; Fisher (2006) p. 163; Helle (2003) p. 376.

- ^ Sayers (2004).

- ^ Power (2005) p. 25; Sayers (2004).

- ^ Antonsson; Crumplin; Conti (2007) p. 203; Power (2005) p. 23.

- ^ Power (2005) pp. 22–23, 22 n. 21.

- ^ Power (2005) pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Ekrem; Mortensen; Fisher (2006) p. 167; Rekdal (2003–2004) p. 257; Helle (2003) p. 377; Orfield (2002) p. 135.

- ^ Ekrem; Mortensen; Fisher (2006) p. 167 n. 57; Power (2005) p. 25; Rekdal (2003–2004) p. 257; Woolf (2003) p. 174; Watt (2000) pp. 11–12; Haddan; Stubbs (1873) pp. 229–230; Diplomatarium Norvegicum (n.d.) vol. 8 § 1.

- ^ Helle (2003) p. 377.

- ^ Beuermann (2002) p. 432.

- ^ Ekrem; Mortensen; Fisher (2006) p. 163; Helle (2003) p. 377.

- ^ Davey, PJ (2006a); Davey, PJ (2006b); Bartlett (1999) p. 823.

- ^ a b Munch; Goss (1874) p. 114; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- ^ Woolf (2003) p. 174.

- ^ Watt (1994) p. 117.

- ^ Woolf (2003) pp. 174–175; Watt (1994) p. 117.

- ^ Woolf (2003) p. 175; Watt (1994) pp. 117–118.

- ^ Beuermann (2002) p. 431.

- ^ McDonald (1997) p. 207.

- ^ Crawford, BE (2014) pp. 70–71; Watt (1994) pp. 117–118.

- ^ Crawford, BE (2014) pp. 70–72; Beuermann (2010) pp. 102–103, 103 n. 10, 106, 106 n. 32; McDonald (2007b) p. 135; Power (2005) p. 22, 22 n. 22; Anderson (1908) p. 245; Lawrie (1910) pp. 114–115 § 6; Howlett (1889) pp. 228–229.

- ^ MacDonald (2013) p. 32.

- ^ Beuermann (2014) p. 93; MacDonald (2013) pp. 31–32; Beuermann (2012) p. 5; Watt (1994) pp. 113, 118.

- ^ MacDonald (2013) p. 32, 32 n. 56.

- ^ Beuermann (2014) p. 93.

- ^ Freke (2002) p. 442; Freke (1990) p. 113.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 77; McDonald (2007b) pp. 70, 123; Anderson (1922) pp. 313, 363–364; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 78–81.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 60; Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) p. 146; Flanagan (2010) p. 195 n. 123; McDonald (2007b) pp. 27 tab. 1; 71; Anderson (1922) pp. 296–297, 313–314; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 76–79.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 78; McDonald (2008) p. 134; McDonald (2007b) pp. 72–73; Duffy (2004d); Clancy; Márkus (1998) pp. 237, 239; Skene (1890) pp. 410–427.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 77; McDonald (2007b) p. 70.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 77; McDonald (2007b) p. 71.

- ^ Oram (1988) p. 100.

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 342; McDonald (1997) pp. 215–216.

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 338; Valante (2010); McDonald (2007b) pp. 27 tab. 1; 75; Brownbill (1919) p. 711 § 5; Oliver (1861) pp. 17–18; Document 1/15/1 (n.d.).

- ^ Power (2005) p. 34 tab.; Anderson (1922) p. 467 n. 2 tab.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) pp. 78, 189; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 116–117.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) pp. 78, 190; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 84–85.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 68; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 66–67.

- ^ McDonald (2007b) p. 70; Duffy (2004b); Freke (2002) p. 442.

- ^ Crawford, DKE (2016) p. 105; Freke (2002) p. 442; Freke (1990) p. 113.

- ^ Freke (1990) p. 118.

- ^ Freke (2002) p. 441.

- ^ Ritchie (1997) p. 101; Power (2013) p. 65; McDonald (2012) p. 156; Power (2005) p. 28.

- ^ Power (2013) p. 65; Power (2005) p. 28; Ritchie (1997) p. 101; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 249 § 12.

- ^ McDonald (2016) p. 343; McDonald (2012) pp. 155–156.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 24, 66, 77; Beuermann (2014) p. 87; Oram (2011) pp. 156, 169; Flanagan (2010) p. 195 n. 123; McDonald (2007b) pp. 70–71, 94, 170; Duffy (2004d); Broderick (2003); Oram (2000) p. 105; Anderson (1922) pp. 313–314; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 78–79.

- ^ McDonald (2019) p. 66; McDonald (2007b) pp. 68–69.

- ^ Oram (2011) p. 156.

- ^ McDonald (2019) pp. 24, 46, 48, 66, 77; Oram (2011) pp. 156, 169; Flanagan (2010) p. 195 n. 123; McDonald (2007b) pp. 70–71, 94, 170; Duffy (2004d); Oram (2000) pp. 105, 124; McDonald (1997) p. 85; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 260; Anderson (1922) pp. 313–314; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 78–79.

- ^ Oram (2013).

- ^ Oram (2013); Woolf (2007) p. 81.

- ^ Beuermann (2014) p. 87; Oram (2013); Woolf (2007) pp. 80–81; McNamee (2005); Brown (2004) pp. 76–78; Duffy (2004d).

- ^ McDonald (2012) p. 150

- ^ Oram (2000), p. 69

- ^ a b c Hollister (2004).

References

Primary sources

- "AM 47 Fol (E) – Eirspennill". Skaldic Project. n.d. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- OL 7115802M.

- Anderson, AO, ed. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Vol. 2. London: Oliver and Boyd.

- Anderson, MO; Anderson, AO, eds. (1938). A Scottish Chronicle Known as the Chronicle of Holyrood. Publications of the Scottish History Society. Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (3 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013a. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013b. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- Bain, J, ed. (1881). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House. .

- Brownbill, J, ed. (1919). The Coucher Book of Furness Abbey. Vol. 2, pt. 3. Chetham Society.

- Butler, R, ed. (1845). Registrum Prioratus Omnium Sanctorum juxta Dublin. Dublin: Irish Archæological Society. OL 23221596M.

- ISBN 0-86241-787-2.

- "Cotton MS Domitian A VII". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- "Cotton MS Julius A VII". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

- "Diplomatarium Norvegicum". Dokumentasjonsprosjektet. n.d. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- "Document 1/5/24". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- "Document 1/14/1". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- "Document 1/14/2". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- "Document 1/14/3". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- "Document 1/15/1". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- Finlay, A; Faulkes, A, eds. (2015). Snorri Sturluson: Heimskringla. Vol. 3. London: ISBN 978-0-903521-93-2.

- Flateyjarbok: En Samling af Norske Konge-Sagaer med Indskudte Mindre Fortællinger om Begivenheder i og Udenfor Norse Same Annaler. Vol. 3. Oslo: P.T. Mallings Forlagsboghandel. 1868. OL 23388689M.

- Grainger, F; Collingwood, WG, eds. (1929). The Register and Records of Holm Cultram. Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society Record Series. Kendal: T Wilson & Son – via British History Online.

- Clarendon Press.

- Hollander, LM, ed. (2011) [1964]. Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway. Austin, TX: OL 25845717M.

- Howlett, R, ed. (1889). Chronicles of the Reigns of Stephen, Henry II, and Richard I. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 4. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Hunter, J, ed. (1844). The Great Rolls of the Pipe for the Second, Third, and Fourth Years of the Reign of King Henry the Second, A.D. 1155, 1156, 1157, 1158. London: OL 19528190M.

- OL 25104622M.

- Jónsson, F, ed. (1916). Eirspennill: Am 47 Fol. Oslo: Julius Thømtes Boktrykkeri. OL 18620939M.

- Lawrie, AC, ed. (1910). Annals of the Reigns of Malcolm and William, Kings of Scotland, A.D. 1153–1214. OL 7217114M.

- Liber S. Marie de Calchou: Registrum Cartarum Abbacie Tironensis de Kelso, 1113–1567. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. 1846.

- Manx Society.

- Oliver, JR, ed. (1861). Monumenta de Insula Manniæ; or, A Collection of National Documents Relating to the Isle of Man. Vol. 2. Douglas, IM: Manx Society.

- ISBN 0-19-822256-4. Archived from the originalon 20 June 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- H. G. Bohn.

- "Royal MS 13 B VIII". British Library. n.d. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- Skene, WF (1890). Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: David Douglas.

- OL 13505351M.

- Storm, G, ed. (1899). Norges Kongesagaer. Vol. 2. Oslo: I.M. Stenersens Forlag.

- ISBN 82-7061-192-1.

- Stubbs, W, ed. (1871). Chronica Magistri Rogeri de Houedene. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 4. Longman & Co.

- "Song of Dermot and the Earl". Corpus of Electronic Texts (27 April 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "Song of Dermot and the Earl". Corpus of Electronic Texts (24 February 2011 ed.). University College Cork. 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (29 August 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (15 August 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- OL 18762756M.

- Vigfusson, G, ed. (1878). Sturlunga Saga Including the Islendinga Saga of Lawman Sturla Thordsson and Other Works. Vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Wilson, J, ed. (1915). The Register of the Priory of St. Bees. Publications of the Surtees Society. Durham: Andrews & Co.

- Wright, T; Forester, T; Hoare, RC, eds. (1905). The Historical Works of Giraldus Cambrensis. London: George Bell & Sons.

Secondary sources

- Abrams, L (2007). "Conversion and the Church in the Hebrides in the Viking Age". In Smith, BB; Taylor, S; Williams, G (eds.). West Over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: ISSN 1569-1462.

- Antonsson, H; Crumplin, S; Conti, A (2007). "A Norwegian in Durham: An Anatomy of a Miracle in Reginald of Durham's Libellus de Admirandis Beati Cuthberti". In Smith, BB; Taylor, S; Williams, G (eds.). West Over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 195–226. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments. Vol. 4. ISBN 0-11-491728-0.

- ISBN 978-1-13905573-4.

- Barrell, ADM (2002) [1995]. The Papacy, Scotland and Northern England, 1342–1378. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44182-X.

- Barrett, J (2004). "Swein Asleiffson (d. 1171?)". required.)

- ISBN 0-19-822473-7.

- Barrow, GWS (1994). "The Date of the Peace between Malcolm IV and Somerled of Argyll". ISSN 0036-9241.

- Barrow, GWS (1995). "Witnesses and the Attestation of Formal Documents in Scotland, Twelfth–Thirteenth Centuries". The Journal of Legal History. 16 (1): 1–20. ISSN 0144-0365.

- Barrow, GWS (2006). "Skye From Somerled to A.D. 1500" (PDF). In Kruse, A; Ross, A (eds.). Barra and Skye: Two Hebridean Perspectives. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 140–154. ISBN 0-9535226-3-6. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- Beuermann, I (2002). "Metropolitan Ambitions and Politics: Kells-Mellifont and Man & the Isles". ISSN 0332-1592.

- Beuermann, I (2008). "Review of RA McDonald, Manx Kingship in its Irish Sea Setting, 1187–1229: King Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty". H-Albion. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- Beuermann, I (2009). "Review of RA McDonald, Manx Kingship in its Irish Sea Setting, 1187–1229: King Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty". JSTOR 40270527.

- Beuermann, I (2010). "'Norgesveldet?' South of Cape Wrath? Political Views Facts, and Questions". In ISBN 978-82-519-2563-1.

- Beuermann, I (2012). The Norwegian Attack on Iona in 1209–10: The Last Viking Raid?. Iona Research Conference, 10 to 12 April 2012. pp. 1–10. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- Beuermann, I (2014). "No Soil for Saints: Why was There No Native Royal Martyr in Man and the Isles". In Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 81–95. ISSN 1569-1462.

- ISBN 978-0-85976-631-9.

- Bridgland, N (2004). "The Medieval Church in Argyll". In Omand, D (ed.). The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Broderick, G (2003). "Tynwald: A Manx Cult-Site and Institution of Pre-Scandinavian Origin?". Studeyrys Manninagh. ISSN 1478-1409. Archived from the originalon 7 February 2009.

- ISBN 0748612386.

- Butter, R (2007). Cill- Names and Saints in Argyll: A Way Towards Understanding the Early Church in Dál Riata? (PhD thesis). Vol. 1. University of Glasgow.

- Caldwell, DH (2016). "The Sea Power of the Western Isles of Scotland in the Late Medieval Period". In Barrett, JH; Gibbon, SJ (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph. Milton Park, Abingdon: ISSN 0583-9106.

- Caldwell, DH; Hall, MA; Wilkinson, CM (2009). "The Lewis Hoard of Gaming Pieces: A Re-examination of Their Context, Meanings, Discovery and Manufacture". Medieval Archaeology. 53 (1): 155–203. S2CID 154568763.

- Clancy, TO (2008). "The Gall-Ghàidheil and Galloway" (PDF). ISSN 2054-9385.

- Coira, MP (2012). By Poetic Authority: The Rhetoric of Panegyric in Gaelic Poetry of Scotland to c. 1700. Edinburgh: ISBN 978-1-78046-003-1.

- Crawford, BE (2014). "The Kingdom of Man and the Earldom of Orkney—Some Comparisons". In Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T (eds.). Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 65–80. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Crawford, DKE (2016). "St Patrick and St Maughold: Saints' Dedications in the Isle of Man". E-Keltoi. 8: 97–158. ISSN 1540-4889.

- Crooks, P (2005a). "Mac Murchada, Diarmait". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 299–302. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Crooks, P (2005b). "Ulster, Earldom of". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 496–497. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- OL 24831804M.

- Davey, P (2002). "At the Crossroads of Power and Cultural Influence: Manx Archaeology in the High Middle Ages" (PDF). In Davey, P; Finlayson, D; Thomlinson, P (eds.). Mannin Revisited: Twelve Essays on Manx Culture and Environment. Edinburgh: The Scottish Society for Northern Studies. pp. 81–102. ISBN 0-9535226-2-8.

- Davey, PJ (2006a). "Christianity in the Celtic Countries [3] Isle of Man". In ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Davey, PJ (2006b). "Sodor and Man, The Diocese of". In Koch, JT (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 1618–1619. ISBN 1-85109-445-8.

- Davey, PJ (2008). "Eleven Years of Archaeological Research at Rushen Abbey, 1998 to 2008" (PDF). Monastic Research Bulletin. 14.

- ISBN 0-521-38069-3.

- Downham, C (2013). "Living on the Edge: Scandinavian Dublin in the Twelfth Century". No Horns on Their Helmets? Essays on the Insular Viking-age. Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Scandinavian Studies. Aberdeen: Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies and The Centre for Celtic Studies, ISSN 2051-6509.

- Duffy, S (1991). "The Bruce Brothers and the Irish Sea World, 1306–29". Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies. 21: 55–86.

- Duffy, S (1992). "Irishmen and Islesmen in the Kingdoms of Dublin and Man, 1052–1171". JSTOR 30007421.

- Duffy, S (1993). Ireland and the Irish Sea Region, 1014–1318 (PhD thesis). hdl:2262/77137.

- Duffy, S (1995). "The First Ulster Plantation: John de Courcy and the Men of Cumbria". In Berry, T; Frame, R; Simms, K (eds.). Colony and Frontier in Medieval Ireland: Essays Presented to J.F. Lydon. London: ISBN 1-85285-122-8.

- Duffy, S (1996). "Ulster and the Irish Sea Region in the Twelfth Century" (PDF). Group for the Study of Irish Historic Settlement. 6: 5–7. ISSN 1393-0966.

- Duffy, S (1998). "Ireland's Hastings: The Anglo-Norman Conquest of Dublin". In ISSN 0954-9927.

- Duffy, S (1999). "Ireland and Scotland, 1014–1169: Contacts and Caveats". In ISBN 1-85182-489-8.

- Duffy, S (2004a). "Courcy, John de (d. 1219?)". required.)

- Duffy, S (2004b). "Godred Crovan (d. 1095)". required.)

- Duffy, S (2004c). "Mac Lochlainn, Muirchertach (d. 1166)". required.)

- Duffy, S (2004d). "Ragnvald (d. 1229)". required.)

- Duffy, S (2005a). "Courcy, John de". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 108–1109. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Duffy, S (2005b). "Town and Crown: The Kings of England and Their City of Dublin". In ISSN 0269-6967.

- Duffy, S (2006). "The Royal Dynasties of Dublin and the Isles in the Eleventh Century". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Dublin. Vol. 7. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 51–65. ISBN 1-85182-974-1.

- Duffy, S (2007). "The Prehistory of the Galloglass". In Duffy, S (ed.). The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0.

- S2CID 189977430.

- Ekrem, I; Mortensen, LB; Fisher, P, eds. (2006). Historia Norwegie. Copenhagen: ISBN 87-635-0612-2.

- Flanagan, MT (1977). "Hiberno-Papal Relations in the Late Twelfth Century". JSTOR 25487421.

- Flanagan, MT (1989). Irish Society, Anglo-Norman Settlers, Angevin Kingship: Interactions in Ireland in the Late Twelfth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822154-1.

- Flanagan, MT (2004a). "Clare, Richard fitz Gilbert de, Second Earl of Pembroke (c.1130–1176)". doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5447. Retrieved 27 November 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- Flanagan, MT (2004b). "Mac Murchada, Diarmait (c.1110–1171)". required.)

- Flanagan, MT (2004c). "Ua Conchobair, Ruaidrí [Rory O'Connor] (c.1116–1198)". required.)

- Flanagan, MT (2010). The Transformation of the Irish Church in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Forte, A; ISBN 978-0-521-82992-2.

- Freke, D (1990). "History". In Robinson, V; McCarroll, D (eds.). The Isle of Man: Celebrating a Sense of Place. Liverpool: ISBN 0-85323-036-6.

- Freke, D (2002). "Conclusions". In Freke, D (ed.). Excavations on St Patrick's Isle, Peel, Isle of Man 1982–88: Prehistoric, Viking, Medieval and Later. Centre for Manx Studies Monographs (series vol. 2). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 437–448.

- French, NE (2015). "Dublin, 1160–1200: Part One". JSTOR 24616064.

- Gade, KE (1994). "1236: Órækja Meiddr ok Heill Gerr" (PDF). In Tómasson, S (ed.). Samtíðarsögur: The Contemporary Sagas. Forprent. Reykjavík: Stofnun Árna Magnússona. pp. 194–207.

- Ghosh, S (2011). Kings' Sagas and Norwegian History: Problems and Perspectives. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. ISSN 1569-1462.

- "Gilchrist, Foster-Brother of King Godred". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371. n.d. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

- ISBN 0-85115-732-7.

- Griffin, PC (2002). The Mac Lochlainn High-Kingship in Late Pre-Norman Ireland (PDF) (PhD thesis). Trinity College, Dublin.

- ISBN 0-521-47299-7.

- required.)

- ISBN 978-0-19-516237-0.

- Jamroziak, E (2008). "Holm Cultram Abbey: A Story of Success?". Northern History. 45 (1): 27–36. S2CID 159643490.

- Jamroziak, E (2011). Survival and Success on Medieval Borders: Cistercian Houses in Medieval Scotland and Pomerania From the Twelfth to the Late Fourteenth Century. Medieval Texts and Cultures of Northern Europe. Turnhout: ISBN 978-2-503-53307-0.

- Jennings, A (2017). "Three Scottish Coastal Names of Note: Earra-Ghàidheal, Satíriseið, and Skotlandsfirðir". In Worthington, D (ed.). The New Coastal History: Cultural and Environmental Perspectives From Scotland and Beyond. Cham: ISBN 978-3-319-64090-7.

- Jennings, AP (2001). "Man, Kingdom of". In ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- JSTOR 25528786.

- S2CID 223924724.

- Kostick, C (2013). Strong Bow: The Norman Invasion of Ireland (EPUB). Dublin: ISBN 978-1-84717-607-3.

- Lowe, C (1988). Early Ecclesiastical Sites in the Northern Isles and Isle of Man: An Archaeological Field Survey (PhD thesis). Vol. 1. Durham University.

- MacDonald, IG (2013). Clerics and Clansmen: The Diocese of Argyll between the Twelfth and Sixteenth Centuries. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Macdonald, P; McQuillan, L; Young, T (n.d.). Data Structure Report: Geophysical Survey and Excavation at Dundrum Castle, County Down, 2012 and 2013 (PDF). Vol. 1.

- MacInnes, IA (2019). "'A Somewhat too Cruel Vengeance was Taken for the Blood of the Slain': Royal Punishment of Rebels, Traitors, and Political Enemies in Medieval Scotland, c.1100–c.1250". In Tracy, L (ed.). Treason: Medieval and Early Modern Adultery, Betrayal, and Shame. Explorations in Medieval Culture. Leiden: Brill. pp. 119–146. LCCN 2019017096.

- Mac Lean, DG (1985a). Early Medieval Sculpture in the West Highlands and Islands of Scotland (PhD thesis). Vol. 1. hdl:1842/7273.

- Mac Lean, DG (1985b). Early Medieval Sculpture in the West Highlands and Islands of Scotland (PhD thesis). Vol. 2. University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/7273.

- Macniven, A (2006). The Norse in Islay: A Settlement Historical Case-Study for Medieval Scandinavian Activity in Western Maritime Scotland (PhD thesis). University of Edinburgh. hdl:1842/8973.

- ISBN 978-0-19-821755-8.

- McDonald, RA (1995). "Images of Hebridean Lordship in the Late Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries: The Seal of Raonall Mac Sorley". Scottish Historical Review. 74 (2): 129–143. JSTOR 25530679.

- McDonald, RA (1997). The Kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's Western Seaboard, c. 1100–c. 1336. Scottish Historical Monographs. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 978-1-898410-85-0.

- McDonald, RA (2007a). "Dealing Death From Man: Manx Sea Power in and around the Irish Sea, 1079–1265". In Duffy, S (ed.). The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 45–76. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0.

- McDonald, RA (2007b). Manx Kingship in its Irish Sea Setting, 1187–1229: King Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-047-2.

- McDonald, RA (2008). "Man, Ireland, and England: The English Conquest of Ireland and Dublin-Manx Relations". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Dublin. Vol. 8. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 131–149. ISBN 978-1-84682-042-7.

- McDonald, RA (2012). "The Manx Sea Kings and the Western Oceans: The Late Norse Isle of Man in its North Atlantic Context, 1079–1265". In Hudson, B (ed.). Studies in the Medieval Atlantic. The New Middle Ages. New York: ISBN 978-1-137-06239-0.

- McDonald, RA (2016). "Sea Kings, Maritime Kingdoms and the Tides of Change: Man and the Isles and Medieval European Change, AD c1100–1265". In Barrett, JH; Gibbon, SJ (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph. Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 333–349. ISSN 0583-9106.

- McDonald, RA (2019). Kings, Usurpers, and Concubines in the Chronicles of the Kings of Man and the Isles. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. S2CID 204624404.

- McDonald, RA; McLean, SA (1992). "Somerled of Argyll: A New Look at Old Problems". Scottish Historical Review. 71 (1–2): 3–22. JSTOR 25530531.

- McIntire, WT (1941). "A Note on Grey Abbey and Other Religious Foundations on Strangford Lough Affiliated to the Abbeys of Cumberland" (PDF). Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archæological Society. 41: 161–173. doi:10.5284/1032950.

- McIntire, WT (1943). "A Note Upon the Connections of Furness Abbey With the Isle of Man". Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archæological Society. 43: 1–19. doi:10.5284/1032950.

- McLeod, W (2002). "Rí Innsi Gall, Rí Fionnghall, Ceannas nan Gàidheal: Sovereignty and Rhetoric in the Late Medieval Hebrides". ISSN 1353-0089.

- McNamee, C (2005). "Olaf (1173/4–1237)". required.)

- Ní Mhaonaigh, M (2018). "Perception and Reality: Ireland c.980–1229". In Smith, B (ed.). The Cambridge History of Ireland. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–156. ISBN 978-1-107-11067-0.

- ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- O'Byrne, E (2005b). "Ua Conchobair, Ruaidrí (c. 1116–1198)". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 466–471. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- O'Byrne, E (2005c). "Ua Conchobair, Tairrdelbach (1088–1156)". In Duffy, S (ed.). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge. pp. 471–474. ISBN 0-415-94052-4.

- Oram, RD (1988). The Lordship of Galloway, c. 1000 to c. 1250 (PhD thesis). hdl:10023/2638.

- Oram, RD (1993). "A Family Business? Colonisation and Settlement in Twelfth- and Thirteenth-Century Galloway". Scottish Historical Review. 72 (2): 111–145. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Oram, RD (2000). The Lordship of Galloway. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 0-85976-541-5.

- Oram, RD (2011). Domination and Lordship: Scotland 1070–1230. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1496-7. Archived from the originalon 18 June 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Oram, RD (2013) [2012]. Alexander II, King of Scots, 1214–1249. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-907909-05-4.

- Orfield, LB (2002) [1953]. The Growth of Scandinavian Law. Union, NJ: The Lawbook Exchange.

- Ó Mainnín, MB (1999). "'The Same in Origin and in Blood': Bardic Windows on the Relationship between Irish and Scottish Gaels in the Period c. 1200–1650". Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies. 38: 1–52. ISSN 1353-0089.

- Pollock, M (2005). "Rebels of the West, 1209–1216". Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies. 50: 1–30. ISSN 1353-0089.

- Power, R (1986). "Magnus Barelegs' Expeditions to the West". Scottish Historical Review. 65 (2): 107–132. JSTOR 25530199.

- Power, R (2005). "Meeting in Norway: Norse-Gaelic Relations in the Kingdom of Man and the Isles, 1090–1270" (PDF). ISSN 0305-9219.

- Power, R (2013). The Story of Iona: An Illustrated History and Guide. London: Canterbury Press Norwich. ISBN 978-1-84825-556-2.

- Prescott, J (2009). Earl Rögnvaldr Kali: Crisis and Development in Twelfth Century Orkney (MA thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/741.

- Purcell, E (2003–2004). "The Expulsion of the Ostmen, 1169–71: The Documentary Evidence". Peritia. 17–18: 276–294. ISSN 0332-1592.

- Ritchie, A (1997). Iona. London: ISBN 0-7134-7855-1.

- Rixson, D (1982). The West Highland Galley. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-874744-86-6.

- Rixson, D (2001). The Small Isles: Canna, Rum, Eigg and Muck. Edinburgh: Birlinn. OL 3544460M.

- Rekdal, JE (2003–2004). "Vikings and Saints–Encounters Vestan um Haf". Peritia. 17–18: 256–275. ISSN 0332-1592.

- "Reports of District Secretaries" (PDF). Saga-Book of the Viking Club Society for Northern Research. 3: 300–325. 1903.

- Rubin, M (2014). The Middle Ages: A Very Short Introduction (EPUB). ISBN 978-0-19-101955-5.

- Salvucci, G (2005). 'The King is Dead': The Thanatology of Kings in the Old Norse Synoptic Histories of Norway, 1035–1161 (PhD thesis). Durham University.

- Sayers, JE (2004). "Adrian IV (d. 1159)". doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/173. Retrieved 11 September 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- Scott, JG (1988). "The Origins of Dundrennan and Soulseat Abbeys" (PDF). Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society. 63: 35–44. ISSN 0141-1292.

- ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Sellar, WDH (2004). "Somerled (d. 1164)". required.)

- Sigurðsson, JV; Bolton, T, eds. (2014). "Index". Celtic-Norse Relationships in the Irish Sea in the Middle Ages, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 215–223. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Simms, K (1998) [1989]. "The Norman Invasion and the Gaelic Recovery". In OL 22502124M.

- Simms, K (2000) [1987]. From Kings to Warlords. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-784-9.

- Stephenson, D (2008). "Madog ap Maredudd, Rex Powissensium". ISSN 0043-2431.

- Strickland, M (2016). Henry the Young King, 1155–1183. New Haven, CT: LCCN 2016009450.

- Taylor, A (2016). The Shape of the State in Medieval Scotland, 1124–1290. Oxford Studies in Medieval European History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-874920-2.

- Thornton, DE (1996). "The Genealogy of Gruffudd ap Cynan". In Maund, KL (ed.). Gruffudd ap Cynan: A Collaborative Biography. Studies in Celtic History. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 79–108. ISSN 0261-9865.

- Valante, MA (2010). "Review of RA McDonald, Manx Kingship in Its Irish Sea Setting, 1187–1229: King Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan Dynasty". JSTOR 27866810.

- Veach, C (2014). Lordship in Four Realms: The Lacy Family, 1166–1241. Manchester Medieval Studies. Manchester: ISBN 978-0-7190-8937-4.

- Veach, C (2018). "Conquest and Conquerors". In Smith, B (ed.). The Cambridge History of Ireland. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 157–181. ISBN 978-1-107-11067-0.

- Wadden, P (2014). "Cath Ruis na Ríg for Bóinn: History and Literature in Twelfth-Century Ireland". Aiste. 4: 11–44.

- ISSN 0020-157X.

- Watt, DER (2000). Medieval Church Councils in Scotland. Edinburgh: ISBN 0-56708731-X.

- Watt, DER (2003). "Scotland: Religion and Piety". In Rigby, SH (ed.). A Companion to Britain in the Later Middle Ages. Blackwell Companions to British History. Malden, MA: ISBN 0-631-21785-1.

- Williams, DGE (1997). Land Assessment and Military Organisation in the Norse Settlements in Scotland, c.900–1266 AD (PhD thesis). University of St Andrews. hdl:10023/7088.

- Williams, G (2007). "'These People were High-Born and Thought Well of Themselves': The Family of Moddan of Dale". In Smith, BB; Taylor, S; Williams, G (eds.). West Over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. pp. 129–152. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Wilson, DM (1973). "Manx Memorial Stones of the Viking Period" (PDF). Saga-Book. 18: 1–18.

- ISBN 0-19-211696-7.

- Woolf, A (2003). "The Diocese of the Sudreyar". In Imsen, S (ed.). Ecclesia Nidrosiensis, 1153–1537: Søkelys på Nidaroskirkens og Nidarosprovinsens Historie. Tapir Akademisk Forlag. pp. 171–181. ISBN 9788251918732.

- Woolf, A (2004). "The Age of Sea-Kings, 900–1300". In Omand, D (ed.). The Argyll Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 94–109. ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Woolf, A (2005). "The Origins and Ancestry of Somerled: Gofraid mac Fergusa and 'The Annals of the Four Masters'". Mediaeval Scandinavia. 15: 199–213.

- Woolf, A (2007). "A Dead Man at Ballyshannon". In Duffy, S (ed.). The World of the Galloglass: Kings, Warlords and Warriors in Ireland and Scotland, 1200–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 77–85. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0.

- Woolf, A (2013). "The Song of the Death of Somerled and the Destruction of Glasgow in 1153". Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History. 14: 1–11.

- Wyatt, D (2009). Slaves and Warriors in Medieval Britain and Ireland, 800–1200. The Northern World: North Europe and the Baltic c. 400–1700 AD. Peoples, Economics and Cultures. Leiden: Brill. ISSN 1569-1462.

- Wyatt, D (2018). "Slavery and Cultural Antipathy". In Pargas, DA; Roşu, F (eds.). Critical Readings on Global Slavery. Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill. pp. 742–799. ISBN 978-90-04-34661-1.

External links

- "Godred, King of the Isles (d.1187)". People of Medieval Scotland, 1093–1371.

Media related to Guðrøðr Óláfsson at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Guðrøðr Óláfsson at Wikimedia Commons

|}