Guttural R

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2015) |

Guttural R is the phenomenon whereby a

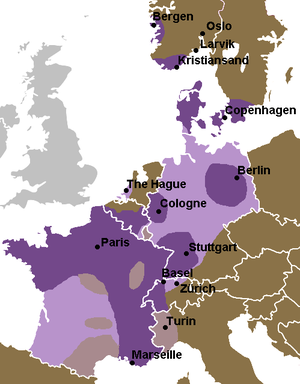

The guttural realization of a lone rhotic consonant is typical in most of what is now France, French-speaking Belgium, most of Germany, large parts of the Netherlands, Denmark, the southern parts of Sweden and southwestern parts of Norway. It is also frequent in Flanders, eastern Austria, Yiddish (and hence Ashkenazi Hebrew), and among all French and some German speakers in Switzerland.

Outside of central Europe, it also occurs as the normal pronunciation of one of two rhotic phonemes (usually replacing an older

Romance languages

French

The r letter in French was historically pronounced as a trill, as was the case in Latin and as is still the case in Italian and Spanish. In Northern France, including Paris, the

The alveolar trill was still the common sound of r in Southern France and in Quebec at the beginning of the 20th century, having been gradually replaced since then, due to Parisian influence, by the uvular pronunciation. The alveolar trill is now mostly associated, even in Southern France and in Quebec, with older speakers and rural settings.[citation needed]

The alveolar trill is still used in French singing in classical choral and opera. It is also used in other French speaking countries as well as on French oversea territories such as French Polynesia due to the influence of the indigenous languages which use the trill.

Portuguese

Standard versions of

- ⟨r⟩ represents a trill when written ⟨rr⟩ between vowels; at the beginning of a word; or following /n/, /l/, /s/, or /ʒ/. Examples: carro, rua, honrar, Israel.

- ⟨r⟩ represents a flap elsewhere, i.e. following a vowel or following any consonant other than /n/, /l/, /s/, or /ʃ/. Examples: caro, quatro, quarto, mar.

In the 19th century, the

retain the alveolar trill. In the rural regions, the alveolar trill is still present, but because most of the country's population currently lives in or near the cities and owing to the mass media, the guttural [ʀ] is now dominant in Portugal.A common realization of the word-initial /ʀ/ in the Lisbon accent is a voiced uvular fricative trill [

The dialect of the fishermen of

In Africa, the classical alveolar trill is mostly still dominant, due to separate development from European Portuguese.

In Brazil, the normal pronunciation of ⟨rr⟩ is voiceless, either as a voiceless velar fricative [x], voiceless uvular fricative [χ] or a voiceless glottal fricative [h].[5] In many dialects, this voiceless sound not only replaces all occurrences of the traditional trill, but is also used for all ⟨r⟩ that is not followed by a vowel (i.e. when at the end of a syllable, which uses a flap in other dialects). The resulting distribution can be described as:

- A flap [ɾ] only for single ⟨r⟩ and only when it occurs either between vowels or between a preceding consonant (other than /n/, /l/, /s/, or /ʃ/) and a following vowel. Examples: caro, quatro.

- A voiceless fricative [x] [χ] or [h] everywhere else: when written ⟨rr⟩; at the beginning of a word; at the end of a word; before a consonant; after /n/, /l/, /s/, or /ʃ/. Examples: carro, rua, honrar, Israel, quarto, mar.

In the three southernmost states, however, the alveolar trill [r] remains frequent, and the distribution of trill and flap is as in Portugal. Some speakers use a guttural fricative instead of a trill, like the majority of Brazilians, but continue to use the flap [ɾ] before consonants (e.g. in quarto) and between vowels (e.g. in caro). Among others, this includes many speakers in the city of

In areas where ⟨r⟩ at the end of a word would be a voiceless fricative, the tendency in colloquial speech is to pronounce this sound very lightly, or omit it entirely. Some speakers may omit it entirely in verb infinitives (amar "to love", comer "to eat", dormir "to sleep") but pronounce it lightly in some other words ending in ⟨r⟩ (mar "sea", mulher "woman", amor "love"). Speakers in Rio often resist this tendency, pronouncing a strong fricative [x] or [χ] at the end of such words. [citation needed]

The voiceless fricative may be partly or fully voiced if it occurs directly before a voiced sound, especially in its weakest form of [h], which is normally voiced to [ɦ]. For example, a speaker whose ⟨rr⟩ sounds like [h] will often pronounce surdo "deaf" as [ˈsuɦdu] or even [ˈsuɦʊdu], with a short epenthetic vowel that mimics the preceding vowel.

Spanish

In most Spanish-speaking territories and regions, guttural or uvular realizations of /r/ are considered a

In the Basque-speaking areas of Spain, the uvular articulation [ʁ] has a higher prevalence among bilinguals than among Spanish monolinguals.[10]

Italian

Guttural realization of /r/ is mostly considered a speech defect in Italian (cf.

Occitan

As with all other Romance languages, the

Breton

Continental West Germanic

The uvular rhotic is most common in

The Frisian languages usually retain an alveolar rhotic.[citation needed]

Dutch and Afrikaans

In modern

Low Saxon

In the

Standard German

Although the first standardized pronunciation dictionary by

In German dialects, the alveolar has survived somewhat more widely than in the standard language, though there are several regions, especially in Central German, where even the broadest rural dialects use a uvular R.[citation needed]

Regardless of whether a uvular or an alveolar pronunciation is used, German post-vocalic "r" is often vocalized to [ (uvular) German.

Yiddish

Yiddish, the traditional language of Ashkenazi Jews in central and eastern Europe, is derived from Middle High German. As such it presumably used the alveolar R at first, but the uvular R then became predominant in many Yiddish dialects. It is unclear whether this happened through independent developments or under influence from modern German (a language widely spoken in large parts of eastern Europe until 1945).

Insular West Germanic

English

Speakers of the traditional English dialect of

The Hiberno-English of northeastern Leinster in Ireland also uses a uvular [ʁ].[23]

North Germanic

Danish and Swedish

The rhotic used in

To some extent in Östergötland and still quite commonly in Västergötland, a mixture of guttural and rolling rhotic consonants (e.g. /ʁ/ and /r/ is used, with the pronunciation depending on the position in the word, the stress of the syllable and in some varieties depending on whether the consonant is geminated. The pronunciation remains if a word that is pronounced with a particular rhotic consonant is put into a compound word in a position where that realization would not otherwise occur if it were part of the same stem as the preceding sound. However, in Östergötland the pronunciation tends to gravitate more towards [w] and in Västergötland the realization is commonly voiced. Common from the time of Gustav III (Swedish king 1771–1792), who was much inspired by French culture and language, was the use of guttural R in the nobility and in the upper classes of Stockholm. This phenomenon vanished in the 1900s. The last well-known non-Southerner who spoke with a guttural R, and did not have a speech defect, was Anders Gernandt, a popular equitation commentator on TV.

Norwegian

Most of Norway uses an

are mutations of [ɾ] and other alveolar or dental consonants, the use of a uvular rhotic means an absence of most retroflex consonants.Icelandic

In Icelandic, the uvular rhotic-like [ʀ] or [ʁ][26] is an uncommon[26] deviation from the normal alveolar trill or flap, and is considered a speech disorder.[27]

Slavic languages

In

Semitic languages

Hebrew

In

].In most forms of

An apparently unrelated uvular rhotic is believed to have appeared in the Tiberian vocalization of Hebrew, where it is believed to have coexisted with additional non-guttural, emphatic articulations of /r/ depending on circumstances.[28]

Yiddish influence

Although an Ashkenazi Jew in the

: 262The alveolar rhotic is still used today in some formal speech, such as radio news broadcasts, and in the past was widely used in television and singing.[citation needed]

Sephardic Hebrew

Many Jewish immigrants to Israel spoke a

Arabic

While most

- pre-modern Baghdadi Arabic.

- The Tigris varieties, a group among the Mesopotamian Arabic in Iraq, for instance in Mosul[30]

- The Jewish and Christian varieties in Baghdad

- The Jewish variety in Algiers

- The variety of Jijel in Algeria[31]

- Some Muslim-urban varieties of Morocco (e.g. in Fes)[32]

- Some Jewish varieties in Morocco.

The uvular /r/ was attested already in vernacular Arabic of the

Ethiopic

In

Akkadian

The majority of Assyriologists deem an alveolar trill or flap the most likely pronunciation of Akkadian /r/ in most dialects. However, there are several indications toward a velar or uvular fricative [ɣ]~[ʁ] particularly supported by John Huehnergard.[37] The main arguments constitute alternations with the voiceless uvular fricative /χ/ (e.g. ruššû/ḫuššû "red"; barmātu "multicolored" (fem. pl.), the spelling ba-aḫ-ma-a-tù is attested).[38] Besides /r/ shows certain phonological parallelisms with /χ/ and other gutturals (especially the glottal stop [ʔ]).[39]

Austronesian

Malayan languages

Guttural R exists among several Malay dialects. While

- Pahang Malay

- Kedah Malay

- Kelantan-Pattani Malay

- Negeri Sembilan Malay

- Sarawak Malay

- Terengganu Malay

- Perak Malay

- Tamiang Malay

- Pontianak Malay

- Palembang Malay

~ Perak Malay and Kedah Malay are the most notable examples.

These dialects mainly use the guttural fricative (

Other Austronesian languages

Other Austronesian languages with similar features are:

- Acehnese

- Alas-Kluet

- Cham

- Minangkabau (closely related to Malay that it might be dialects of the same language)

- Lampung

- Piuma

- Sapediq

- Rinaxekerek

- Sinvaudjan

Other language families

Basque

Khmer

Whereas standard Khmer uses an alveolar trill for /r/, the colloquial Phnom Penh dialect uses a uvular pronunciation for the phoneme, which may be elided and leave behind a residual tonal or register contrast.[40]

Bantu

Sesotho originally used an alveolar trill /r/, which has shifted to uvular /ʀ/ in modern times.[citation needed]

Hill-Maṛia

Rhotic-agnostic guttural consonants written as rhotics

There are languages where certain indigenous guttural consonants came to be written with symbols used in other languages to represent rhotics, thereby giving the superficial appearance of a guttural R without actually functioning as true rhotic consonants.

Inuit languages

The

[ʐ] phoneme, which Greenlandic and Inuktitut do not have.See also

References

Notes

- ^ Map based on Trudgill (1974:220)

- JSTOR 43342245.

- ^ Molière (1670). Le bourgeois gentilhomme. Imprimerie nationale.

Et l'R, en portant le bout de la langue jusqu'au haut du palais, de sorte qu'étant frôlée par l'air qui sort avec force, elle lui cède, et revient toujours au même endroit, faisant une manière de tremblement : Rra. [And the R, placing the tip of the tongue to the height of the palate so that, when it is grazed by air leaving the mouth with force, it [the tip of the tongue] falls down and always comes back to the same place, making a kind trembling.]

- ^ Grønnum (2005:157)

- ^ Navarro-Tomás, T. (1948). "El español en Puerto Rico". Contribución a la geografía lingüística latinoamericana. Río Piedras: Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico, pp. 91-93.

- ^ López-Morales, H. (1983). Estratificación social del español de San Juan de Puerto Rico. México: UNAM.

- ^ López-Morales, H. (1992). El español del Caribe. Madrid: MAPFRE, p. 61.

- ^ Jiménez-Sabater, M. (1984). Más datos sobre el español de la República Dominicana. Santo Domingo: Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo, p. 87.

- ^ Walter de Gruyter, 2003

- ^ Romano A. (2013). "A preliminary contribution to the study of phonetic variation of /r/ in Italian and Italo-Romance". In: L. Spreafico & A. Vietti (eds.), Rhotics. New data and perspectives. Bolzano/Bozen: BU Press, 209–225 [1] Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ De Taal van Overijssel. Over de taal van Steenwijk.

- ^ De Taal van Overijssel. Over de taal van Kampen.

- ^ De Taal van Overijssel. Over de taal van Zwolle.

- ^ De Taal van Overijssel. Over de taal van Deventer

- ISBN 978-90-6697-228-5

- ISBN 978-90-6697-228-5.

- ^ Wells, J.C. 1982. Accents of English 2: The British Isles. Cambridge University Press. Page 368

- ^ Survey of English Dialects, Heddon-on-the-Wall, Northumberland

- ^ Survey of English Dialects, Ebchester, County Durham

- ^ Millennium Memory Bank, Alnwick, Northumberland

- ^ Millennium Memory Bank, Butterknowle, County Durham

- ISBN 978-0-521-85299-9. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ^ Chambers, J.K. and Trudgill, P. (1998): Dialectology. Cambridge University Press, p. 173f.

- ^ "Spreiing av skarre-r-en". Språkrådet (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ a b Kristín María Gísladóttir (2014). "Framburður MND-veikra á Íslandi" (PDF). p. 22.

- ^ "Skýrsla um stöðu barna og ungmenna með tal- og málþroskaröskun" (PDF). 2012. p. 17.

- ^ Khan, Geoffrey (1995), The Pronunciation of reš in the Tiberian Tradition of Biblical Hebrew, in: Hebrew Union College Annual, Vol.66, p.67-88.

- ^ ISBN 978-1403917232.

- ^ Otto Jastrow (2007), Iraq, in: The Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, Vol. 2, p.414-416

- ^ Philippe Marçais (1956), Le Parler Arabe de Djidjelli (Nord Constantinois, Algérie), Paris, 16–17; cf. also Marcel Cohen (1912), Le Parler Arabe des Juifs d’Alger (= Collection linguistique 4), Paris, p.27

- ^ Georges-Séraphin Colin (1987), Morocco (The Arabic Dialects), in: E. J. Brill’s First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913–1936, Vol. 6, Leiden, 599

- ^ Farida Abu-Haidar (1991), Christian Arabic of Baghdad (= Semitica Viva 7), Wiesbaden, p.9-10.

- ^ Otto Jastrow (1979), Zur arabischen Mundart von Mosul, in: Zeitschrift für arabische Linguistik, Vol. 2., p.38.

- ^ Edward Ullendorf (1955), The Semitic Languages of Ethiopia, London, p.124-125.

- ^ Edward Lipiński (1997), Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar (= Orientalia Lovaniensa Analecta 80), Leuven, p.132-133.

- ^ John Huehnergard and Christopher Woods (2004), Akkadian and Eblaite, in: Roger D. Woodard Roger (ed.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World’s Ancient Languages, Cambridge, p.230-231.

- ^ Wolfram von Soden (1995), Grundriß der akkadischen Grammatik (= Analecta Orientalia 33), Rom, p.44 (§ 35); see also Benno Landsberger (1964), Einige unerkannt gebliebene oder verkannte Nomina des Akkadischen, in: Die Welt des Orients 3/1, p.54.

- ^ John Huehnergard (2013), Akkadian e and Semitic Root Integrity, in: Babel und Bibel 7: Annual of Ancient Near Eastern, Old Testament and Semitic Studies (= Orientalia et Classica 47), p.457 (note 45); see also Edward L. Greenstein (1984), The Phonology of Akkadian Syllable Structure, in: Afroasiatic Linguistics 9/1, p.30.

- ISBN 0-226-76288-2.

- ISBN 978-1-139-43533-8.

Works cited

- Fougeron, Cecile; Smith, Caroline L (1993), "Illustrations of the IPA:French", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 23 (2): 73–76, S2CID 249404451

- ISBN 87-500-3865-6

- S2CID 145148233