Gwalior Fort

| Gwalior Fort | |

|---|---|

| Madhya Pradesh,

Fort | |

| Site information | |

| Owner |

|

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 6th century, The modern-day fort, consisting a defensive structure and two palaces was built by King Man Singh Tomar,[1] later renovated by Scindia ruler under the Supervision of General Sardar Surve in 1916 |

| In use | Yes |

| Materials | Sandstone and lime mortar |

| Battles/wars | Numerous |

| Events | Numerous |

The Gwalior Fort, commonly known as the Gwālīyar Qila, is a

The present-day fort consists of a defensive structure and two main palaces, "Man Mandir" and

Etymology

The word Gwalior is derived from one of the names for Gwalipa.[5] According to legend, Gwalipa cured the local chieftain Suraj Sen of leprosy, and in gratitude, Suraj Sen founded the city of Gwalior in his name.[6]

Topography

-

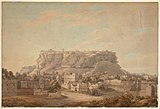

Gwalior Fort seen from the Residency. 10 December 1868.

-

Gwalior Fort map 1911 (click to see details)

The fort is built on an outcrop of

History

The exact period of Gwalior Fort's construction is uncertain.[8] According to a local legend, the fort was built by a local king named Suraj Sen in 3 CE. He was cured of leprosy, when a sage named Gwalipa offered him the water from a sacred pond, which now lies within the fort. The grateful king constructed a fort and named it after the sage. The sage bestowed the title Pal ("protector") upon the king and told him that the fort would remain in his family's possession, as long as they bear this title. 83 descendants of Suraj Sen Pal controlled the fort, but the 84th, named Tej Karan, lost it.[1]

The inscriptions and monuments found within what is now the fort campus indicate that it may have existed as early as the beginning of the 6th century.

The fort definitely existed by the 10th century, when it is first mentioned in the historical records. The

In 1398, the fort came under the control of the

Within a decade, the

There were frequent changes in the control of the fort between the

Structures

The fort and its premises are well maintained and house many historic monuments including palaces, temples and water tanks. There are also a number of palaces (mahal) including the Man mandir, the Gujari, the Jahangir, the Karan, and the Shah Jahan.[26] The fort covers an area of 3 square kilometres (1.2 sq mi) and rises 11 metres (36 ft). Its rampart is built around the edge of the hill, connected by six

There are two gates: one on the northeast side with a long access ramp and the other on the southwest. The main entrance is the ornate Elephant gate (Hathi Pul). The other is the Badalgarh Gate. The Man Mandir palace or citadel is located at the northeast end of the fort. It was built in the 15th century and refurbished in 1648. The water tanks or reservoirs of the fort could provide water to a 15,000 strong garrison, the number required to secure the fort.[citation needed]

The second

Major Monuments

Jain temples

Siddhachal Jain Temple Caves were built in 7th to 15th century. There are eleven Jain temples inside Gwalior fort dedicated to the Jain Tirthankaras. On the southern side are 21 temples cut into the rock with intricately carved of the tirthankaras. Tallest Idol is image of Rishabhanatha or Adinatha, the 1st Tirthankara, is 58 feet 4 inches (17.78 m) high.[29][30][31]

Main Temple

Urvahi

The entire area of Gwalior fort is divided into five groups namely Urvahi, Northwest, Northeast, Southwest and the Southeast areas. In the Urvahi area 24 idols of Tirthankar in the padmasana posture, 40 in the kayotsarga posture and around 840 idols carved on the walls and pillars are present. The largest idol is a 58 feet 4 inches high idol of Adinatha outside the Urvahi gate and a 35 feet high idol of Suparshvanatha in the Padmasana in Paththar-ki bavadi (stone tank) area.[32]

Gopachal

There are around 1500 idols on the

Here is a very beautiful and miraculous[

Main colossus of this Kshetra is Parsvanatha's, 42 feet high and 30 feet wide. Together with the place of precept by Bhagwan Parsvanath. This is also the place where Shri 1008 Supratishtha Kevali attained nirvana. There are 26 Jain temples more on this hill.[33]

Mughal Invasion: In 1527, Babur army attacked Gwalior Fort and de-faced these statues.[30] In spite of invasion the early Jaina sculptures of Gwalior have survived in fairly good condition so that their former splendour is not lost.

Teli ka mandir

The Teli ka Mandir is a Hindu temple built by the Pratihara emperor Mihira Bhoja.[35][36]

It is the oldest part of the fort and has a blend of south and north

Garuda monument

Close to the Teli ka Mandir temple is the

Sahastrabahu (Sas-Bahu) temple

The

, it is pyramidal in shape, built of red sandstone with several stories of beams and pillars but no arches.Gurdwara Data Bandi Chhor

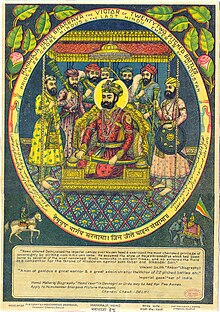

Gurdwara Data Bandi Chhor was built during 1970s and 1980s at the place where 6th

Palace

Man mandir palace

The Man mandir palace was built by the King of Tomar Dynasty – Maharaja Man Singh in 15th century. Man Mandir is often referred as a Painted Palace because the painted effect of the Man Mandir Palace is due to the use of styled tiles of turquoise, green and yellow used extensively in a geometric pattern.[citation needed]

Hathi Pol

The Hathi Pol gate (or Hathiya Paur), located on the southeast, leads to the Man mandir palace. It is the last of a series of seven gates. It is named for a life-sized statue of an elephant (hathi) that once adorned the gate.[citation needed] The gate was built in stone with cylindrical towers crowned with cupola domes. Carved parapets link the domes.

Karn mahal

The Karan mahal is another significant monument at Gwalior Fort. The Karn mahal was built by the second king of the Tomar dynasty, Kirti Singh. He was also known as Karn Singh, hence the name of the palace.[citation needed]

Vikram mahal

The Vikram mahal (also known as the Vikram mandir, as it once hosted a temple of

Chhatri of Bhim Singh Rana

This

Museum

The Gujari Mahal now a museum, was built by Raja

Other monuments

There are several other monuments built inside the fort area. These include the Scindia School (Originally an exclusive school for the sons of Indian princes and nobles) that was founded by Madho Rao Scindia in 1897.

Gallery

-

Interior of Jain Temple, Gwalior Fort

-

Pond at Gwalior Fort.

-

View of Gwalior Fort from the north-west. c. 1790

-

The fort bastions.

-

The north room, Man Mandir.

-

Gate of Teli ka Mandir.

-

Gwalior Fort - Morning View

-

Gwalior fort

-

Gurudwara Shri Data Bandi Chhor Shahib

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Paul E. Schellinger & Robert M. Salkin 1994, p. 312.

- ISBN 978-0-14-193742-7.

Other claiming to be Rajput and descent from Solar and lunar lines established themselves as local kings in Western and Central India. Among these were the Chandelas present in 12th century in Bundelkhand, the Tomaras also subject to the earlier Pratiharas ruling in Haryana region near Dhilaka, now Delhi, around 736 AD and later established themselves in Gwalior region

- ^ You Can Visit the World's Oldest Zero at a Temple in India Archived 16 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Smithsonian magazine.

- ISBN 978-1786340634.]

In a temple on the path up to Gwalior Fort [...] where we find a circular zero in the terminal position.

[page needed - ^ Fodor E. et al. "Fodor's India." D. McKay 1971. p. 293. Accessed at Google Books 30 November 2013.]

- ^ William Curtis, Fodor, Eugene, 1905 Fodor's India D. McKay., 1971

- ISBN 978-1108072540Cambridge University Press 2011. p. 65 Accessed at Google Books 30 November 2013.

- ^ a b Konstantin Nossov & Brain Delf 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, p. 59.

- ^ Sisirkumar Mitra 1977, pp. 80–82.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-5503-8.

- ^ a b c Paul E. Schellinger & Robert M. Salkin 1994, p. 314.

- ^ a b c d Torton E. "A gazetteer of the territories under the government of the East-India company, and of the native states on the continent of India, Volume 2" W. H. Allen & Co. 1854.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech, Martyrdom in the Sikh Tradition, Oxford University Press, pages 118-121

- ISBN 978-8170102458, pages 18-19

- ISBN 978-1780762500, pages 48-55

- ^ V. D. Mahajan (1970). Muslim Rule In India. S. Chand, New Delhi, p.223.

- ISBN 9781576073551.

- ^ ISBN 9781441117083.

- ISBN 978-8173802041. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2015.)

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help - ^ The Sikh Review, Volumes 42-43, Issues 491-497. Sikh Cultural Centre. 1994. pp. 15–16.

- ISBN 978-0-19-874557-0.

- ^ a b Tony McClenaghan 1996, p. 131.

- ^ Paul E. Schellinger & Robert M. Salkin 1994, p. 316.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "History Of Gwalior | ग्वालियर का इतिहास". YouTube.

- ^ "Temples of Gwalior" Archived 20 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Kamat's Potpourri Webpage. Accessed 1 December 2013.

- ^ You Can Visit the World's Oldest Zero at a Temple in India Archived 16 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Smithsonian magazine.

- ISBN 978-1786340634.]

In a temple on the path up to Gwalior Fort [...] where we find a circular zero in the terminal position.

[page needed - ISBN 978-81-208-1534-6.

- ^ a b c d Gwalior Fort: Rock Sculptures, A Cunningham, Archaeological Survey of India, pp. 364–370

- ^ Gwalior Fort Archived 15 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Archaeological Survey of India, Bhopal Circle, India (2014)

- ^ "Jain Samaj". Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ^ "jain.org.in". Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- ISBN 978-81-263-1155-2.

- ISBN 978-0-226-53230-1.

- ISBN 978-0-87413-399-8.

- ISBN 0-87413-399-8.

- ^ ASI Report: Gwalior, A Cunningham, pp. 356–359

- ISBN 978-93-5086-199-8.

- ^ Henry Hardy Cole; (Curator of Ancient Monuments, India) (1882). Preservation of National Monuments: Report of the Curator of Ancient Monuments in India (Report). Simla: Government Central Branch Press. p. 17.

- ISBN 978-81-208-1534-6.

- ISBN 978-0-87413-399-8.

Bibliography

- Konstantin Nossov; Brain Delf (2006). Indian Castles 1206–1526 (Illustrated ed.). Osprey. ISBN 1-84603-065-X.

- Paul E. Schellinger; Robert M. Salkin, eds. (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Vol. 5. Routledge/Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1884964046.

- Sisirkumar Mitra (1977). The Early Rulers of Khajurāho. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120819979.

- Tony McClenaghan (1996). Indian Princely Medals. Lancer. ISBN 978-1897829196.

- Tillotson G. H. R. "The Rajput Palaces – The Development of an Architectural Style" Yale University Press. New Haven and London 1987. First edition. Hardback. ISBN 0-300-03738-4

External links

- Interesting Facts About Gwalior Fort

Gwalior Fort travel guide from Wikivoyage

Gwalior Fort travel guide from Wikivoyage