Water

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Water

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Oxidane | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|||

| 3587155 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.028.902 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 117 | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

RTECS number

|

| ||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| H 2O | |||

| Molar mass | 18.01528(33) g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Almost colorless or white crystalline solid, almost colorless liquid, with a hint of blue, colorless gas[3] | ||

| Odor | Odorless | ||

| Density | |||

| Melting point | 0.00 °C (32.00 °F; 273.15 K) [b] | ||

| Boiling point | 99.98 °C (211.96 °F; 373.13 K)[16][b] | ||

| Solubility | Poorly soluble in . | ||

| Vapor pressure | 3.1690 kilopascals or 0.031276 atm at 25 °C[8] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 13.995[9][10][a] | ||

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.995 | ||

Conjugate acid

|

Hydronium H3O+ (pKa = 0) | ||

Conjugate base

|

Hydroxide OH– (pKb = 0) | ||

Thermal conductivity

|

0.6065 W/(m·K)[13] | ||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.3330 (20 °C)[14] | ||

| Viscosity | 0.890 mPa·s (0.890 cP)[15] | ||

| Structure | |||

| Hexagonal | |||

| C2v | |||

Bent

| |||

| 1.8546 D[17] | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

75.385 ± 0.05 J/(mol·K)[16] | ||

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

69.95 ± 0.03 J/(mol·K)[16] | ||

Std enthalpy of (ΔfH⦵298)formation |

−285.83 ± 0.04 kJ/mol[7][16] | ||

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

−237.24 kJ/mol[7] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Drowning Avalanche (as snow) Water intoxication | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | SDS | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Other cations

|

| ||

Related solvents

|

|||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Water (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

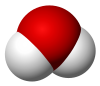

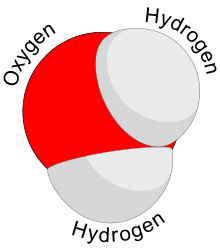

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula H2O. It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless,[c] and nearly colorless chemical substance, and it is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a solvent[19]). It is vital for all known forms of life, despite not providing food energy or organic micronutrients. Its chemical formula, H2O, indicates that each of its molecules contains one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms, connected by covalent bonds. The hydrogen atoms are attached to the oxygen atom at an angle of 104.45°.[20] In liquid form, H2O is also called "Water" at standard temperature and pressure.

Because Earth's environment is relatively close to water's triple point, water exists on Earth as a solid, a liquid, and a gas.[21] It forms precipitation in the form of rain and aerosols in the form of fog. Clouds consist of suspended droplets of water and ice, its solid state. When finely divided, crystalline ice may precipitate in the form of snow. The gaseous state of water is steam or water vapor.

Water covers about 71% of the Earth's surface, with seas and oceans making up most of the water volume (about 96.5%).

Water plays an important role in the

Etymology

The word water comes from Old English wæter, from Proto-Germanic *watar (source also of Old Saxon watar, Old Frisian wetir, Dutch water, Old High German wazzar, German Wasser, vatn, Gothic 𐍅𐌰𐍄𐍉 (wato)), from Proto-Indo-European *wod-or, suffixed form of root *wed- ('water'; 'wet').[27] Also cognate, through the Indo-European root, with Greek ύδωρ (ýdor; from Ancient Greek ὕδωρ (hýdōr), whence English 'hydro-'), Russian вода́ (vodá), Irish uisce, and Albanian ujë.

History

On Earth

One factor in estimating when water appeared on Earth is that water is continually being lost to space. H2O molecules in the atmosphere are broken up by photolysis, and the resulting free hydrogen atoms can sometimes escape Earth's gravitational pull. When the Earth was younger and less massive, water would have been lost to space more easily. Lighter elements like hydrogen and helium are expected to leak from the atmosphere continually, but isotopic ratios of heavier noble gases in the modern atmosphere suggest that even the heavier elements in the early atmosphere were subject to significant losses.[28] In particular, xenon is useful for calculations of water loss over time. Not only is it a noble gas (and therefore is not removed from the atmosphere through chemical reactions with other elements), but comparisons between the abundances of its nine stable isotopes in the modern atmosphere reveal that the Earth lost at least one ocean of water early in its history, between the Hadean and Archean eons.[29][clarification needed]

Any water on Earth during the latter part of its accretion would have been disrupted by the

Geological evidence also helps constrain the time frame for liquid water existing on Earth. A sample of pillow basalt (a type of rock formed during an underwater eruption) was recovered from the Isua Greenstone Belt and provides evidence that water existed on Earth 3.8 billion years ago.[33] In the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt, Quebec, Canada, rocks dated at 3.8 billion years old by one study[34] and 4.28 billion years old by another[35] show evidence of the presence of water at these ages.[33] If oceans existed earlier than this, any geological evidence has yet to be discovered (which may be because such potential evidence has been destroyed by geological processes like crustal recycling). More recently, in August 2020, researchers reported that sufficient water to fill the oceans may have always been on the Earth since the beginning of the planet's formation.[36][37][38]

Unlike rocks, minerals calledProperties

Water (

States

Along with oxidane, water is one of the two official names for the chemical compound H

2O;

Density

Water differs from most liquids in that it becomes less dense as it freezes.[d] In 1 atm pressure, it reaches its maximum density of 999.972 kg/m3 (62.4262 lb/cu ft) at 3.98 °C (39.16 °F), or almost 1,000 kg/m3 (62.43 lb/cu ft) at almost 4 °C (39 °F).[52][53] The density of ice is 917 kg/m3 (57.25 lb/cu ft), an expansion of 9%.[54][55] This expansion can exert enormous pressure, bursting pipes and cracking rocks.[56]

In a lake or ocean, water at 4 °C (39 °F) sinks to the bottom, and ice forms on the surface, floating on the liquid water. This ice insulates the water below, preventing it from freezing solid. Without this protection, most aquatic organisms residing in lakes would perish during the winter.[57]

Magnetism

Water is a diamagnetic material.[58] Though interaction is weak, with superconducting magnets it can attain a notable interaction.[58]

Phase transitions

At a pressure of one

The melting and boiling points depend on pressure. A good approximation for the rate of change of the melting temperature with pressure is given by the Clausius–Clapeyron relation:

where and are the molar volumes of the liquid and solid phases, and is the molar latent heat of melting. In most substances, the volume increases when melting occurs, so the melting temperature increases with pressure. However, because ice is less dense than water, the melting temperature decreases.[51] In glaciers, pressure melting can occur under sufficiently thick volumes of ice, resulting in subglacial lakes.[61][62]

The Clausius-Clapeyron relation also applies to the boiling point, but with the liquid/gas transition the vapor phase has a much lower density than the liquid phase, so the boiling point increases with pressure.[63] Water can remain in a liquid state at high temperatures in the deep ocean or underground. For example, temperatures exceed 205 °C (401 °F) in Old Faithful, a geyser in Yellowstone National Park.[64] In hydrothermal vents, the temperature can exceed 400 °C (752 °F).[65]

At

Triple and critical points

On a pressure/temperature phase diagram (see figure), there are curves separating solid from vapor, vapor from liquid, and liquid from solid. These meet at a single point called the triple point, where all three phases can coexist. The triple point is at a temperature of 273.16 K (0.01 °C; 32.02 °F) and a pressure of 611.657 pascals (0.00604 atm; 0.0887 psi);[69] it is the lowest pressure at which liquid water can exist. Until 2019, the triple point was used to define the Kelvin temperature scale.[70][71]

The water/vapor phase curve terminates at 647.096 K (373.946 °C; 705.103 °F) and 22.064 megapascals (3,200.1 psi; 217.75 atm).

Phases of ice and water

The normal form of ice on the surface of Earth is

The details of the chemical nature of liquid water are not well understood; some theories suggest that its unusual behaviour is due to the existence of two liquid states.[53][80][81][82]

Taste and odor

Pure water is usually described as tasteless and odorless, although

Color and appearance

Pure water is

In nature, the color may also be modified from blue to green due to the presence of suspended solids or algae.

In industry, near-infrared spectroscopy is used with aqueous solutions as the greater intensity of the lower overtones of water means that glass cuvettes with short path-length may be employed. To observe the fundamental stretching absorption spectrum of water or of an aqueous solution in the region around 3,500 cm−1 (2.85 μm)[88] a path length of about 25 μm is needed. Also, the cuvette must be both transparent around 3500 cm−1 and insoluble in water; calcium fluoride is one material that is in common use for the cuvette windows with aqueous solutions.

The Raman-active fundamental vibrations may be observed with, for example, a 1 cm sample cell.

Aquatic plants, algae, and other photosynthetic organisms can live in water up to hundreds of meters deep, because sunlight can reach them. Practically no sunlight reaches the parts of the oceans below 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) of depth.

The refractive index of liquid water (1.333 at 20 °C (68 °F)) is much higher than that of air (1.0), similar to those of alkanes and ethanol, but lower than those of glycerol (1.473), benzene (1.501), carbon disulfide (1.627), and common types of glass (1.4 to 1.6). The refraction index of ice (1.31) is lower than that of liquid water.

Molecular polarity

In a water molecule, the hydrogen atoms form a 104.5° angle with the oxygen atom. The hydrogen atoms are close to two corners of a tetrahedron centered on the oxygen. At the other two corners are

Other substances have a tetrahedral molecular structure, for example

Water is a good polar

Many organic substances (such as

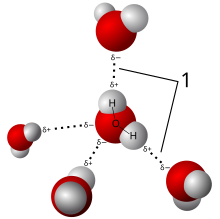

Hydrogen bonding

Because of its polarity, a molecule of water in the liquid or solid state can form up to four

These bonds are the cause of water's high surface tension[94] and capillary forces. The capillary action refers to the tendency of water to move up a narrow tube against the force of gravity. This property is relied upon by all vascular plants, such as trees.[citation needed]

Self-ionization

Water is a weak solution of hydronium hydroxide—there is an equilibrium 2H

2O ⇌ H

3O+

+ OH−

, in combination with solvation of the resulting hydronium and hydroxide ions.

Electrical conductivity and electrolysis

Pure water has a low

Liquid water can be split into the elements hydrogen and oxygen by passing an electric current through it—a process called electrolysis. The decomposition requires more energy input than the heat released by the inverse process (285.8 kJ/mol, or 15.9 MJ/kg).[96]

Mechanical properties

Liquid water can be assumed to be incompressible for most purposes: its compressibility ranges from 4.4 to 5.1×10−10 Pa−1 in ordinary conditions.[97] Even in oceans at 4 km depth, where the pressure is 400 atm, water suffers only a 1.8% decrease in volume.[98]

The

Reactivity

Metallic elements which are more

On Earth

Hydrology is the study of the movement, distribution, and quality of water throughout the Earth. The study of the distribution of water is hydrography. The study of the distribution and movement of groundwater is hydrogeology, of glaciers is glaciology, of inland waters is limnology and distribution of oceans is oceanography. Ecological processes with hydrology are in the focus of ecohydrology.

The collective mass of water found on, under, and over the surface of a planet is called the hydrosphere. Earth's approximate water volume (the total water supply of the world) is 1.386 billion cubic kilometres (333 million cubic miles).[23]

Liquid water is found in bodies of water, such as an ocean, sea, lake, river, stream, canal, pond, or puddle. The majority of water on Earth is seawater. Water is also present in the atmosphere in solid, liquid, and vapor states. It also exists as groundwater in aquifers.

Water is important in many geological processes. Groundwater is present in most

Water cycle

The water cycle (known scientifically as the hydrologic cycle) is the continuous exchange of water within the

Water moves perpetually through each of these regions in the water cycle consisting of the following transfer processes:

- evaporation from oceans and other water bodies into the air and transpiration from land plants and animals into the air.

- precipitation, from water vapor condensing from the air and falling to the earth or ocean.

- runofffrom the land usually reaching the sea.

Most water vapors found mostly in the ocean returns to it, but winds carry water vapor over land at the same rate as runoff into the sea, about 47

.Water runoff often collects over watersheds flowing into rivers. Through erosion, runoff shapes the environment creating river valleys and deltas which provide rich soil and level ground for the establishment of population centers. A flood occurs when an area of land, usually low-lying, is covered with water which occurs when a river overflows its banks or a storm surge happens. On the other hand, drought is an extended period of months or years when a region notes a deficiency in its water supply. This occurs when a region receives consistently below average precipitation either due to its topography or due to its location in terms of latitude.

Water resources

Water resources are natural resources of water that are potentially useful for humans,[102] for example as a source of drinking water supply or irrigation water. Water occurs as both "stocks" and "flows". Water can be stored as lakes, water vapor, groundwater or aquifers, and ice and snow. Of the total volume of global freshwater, an estimated 69 percent is stored in glaciers and permanent snow cover; 30 percent is in groundwater; and the remaining 1 percent in lakes, rivers, the atmosphere, and biota.[103] The length of time water remains in storage is highly variable: some aquifers consist of water stored over thousands of years but lake volumes may fluctuate on a seasonal basis, decreasing during dry periods and increasing during wet ones. A substantial fraction of the water supply for some regions consists of water extracted from water stored in stocks, and when withdrawals exceed recharge, stocks decrease. By some estimates, as much as 30 percent of total water used for irrigation comes from unsustainable withdrawals of groundwater, causing groundwater depletion.[104]

Seawater and tides

Seawater contains about 3.5% sodium chloride on average, plus smaller amounts of other substances. The physical properties of seawater differ from fresh water in some important respects. It freezes at a lower temperature (about −1.9 °C (28.6 °F)) and its density increases with decreasing temperature to the freezing point, instead of reaching maximum density at a temperature above freezing. The salinity of water in major seas varies from about 0.7% in the Baltic Sea to 4.0% in the Red Sea. (The Dead Sea, known for its ultra-high salinity levels of between 30 and 40%, is really a salt lake.)

Effects on life

From a biological standpoint, water has many distinct properties that are critical for the proliferation of life. It carries out this role by allowing organic compounds to react in ways that ultimately allow replication. All known forms of life depend on water. Water is vital both as a solvent in which many of the body's solutes dissolve and as an essential part of many metabolic processes within the body. Metabolism is the sum total of anabolism and catabolism. In anabolism, water is removed from molecules (through energy requiring enzymatic chemical reactions) in order to grow larger molecules (e.g., starches, triglycerides, and proteins for storage of fuels and information). In catabolism, water is used to break bonds in order to generate smaller molecules (e.g., glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids to be used for fuels for energy use or other purposes). Without water, these particular metabolic processes could not exist.

Water is fundamental to both photosynthesis and respiration. Photosynthetic cells use the sun's energy to split off water's hydrogen from oxygen.[105] In the presence of sunlight, hydrogen is combined with CO

2 (absorbed from air or water) to form glucose and release oxygen.[106] All living cells use such fuels and oxidize the hydrogen and carbon to capture the sun's energy and reform water and CO

2 in the process (cellular respiration).

Water is also central to acid-base neutrality and enzyme function. An acid, a hydrogen ion (H+

, that is, a proton) donor, can be neutralized by a base, a proton acceptor such as a hydroxide ion (OH−

) to form water. Water is considered to be neutral, with a

Aquatic life forms

Earth's surface waters are filled with life. The earliest life forms appeared in water; nearly all fish live exclusively in water, and there are many types of marine mammals, such as dolphins and whales. Some kinds of animals, such as amphibians, spend portions of their lives in water and portions on land. Plants such as kelp and algae grow in the water and are the basis for some underwater ecosystems. Plankton is generally the foundation of the ocean food chain.

Aquatic vertebrates must obtain oxygen to survive, and they do so in various ways. Fish have

-

Some of the biodiversity of a coral reef

-

Some marine diatoms – a key phytoplankton group

-

Squat lobster and Alvinocarididae shrimp at the Von Damm hydrothermal field survive by altered water chemistry.

Effects on human civilization

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

Civilization has historically flourished around rivers and major waterways;

Health and pollution

Water fit for human consumption is called drinking water or potable water. Water that is not potable may be made potable by filtration or distillation, or by a range of other methods. More than 660 million people do not have access to safe drinking water.[107][108]

Water that is not fit for drinking but is not harmful to humans when used for swimming or bathing is called by various names other than potable or drinking water, and is sometimes called

Water reclamation is the process of converting wastewater (most commonly sewage, also called municipal wastewater) into water that can be reused for other purposes. There are 2.3 billion people who reside in nations with water scarcities, which means that each individual receives less than 1,700 cubic metres (60,000 cu ft) of water annually. 380 billion cubic metres (13×1012 cu ft) of municipal wastewater are produced globally each year.[109][110][111]

Freshwater is a renewable resource, recirculated by the natural

In developing countries, 90% of all municipal wastewater still goes untreated into local rivers and streams.[113] Some 50 countries, with roughly a third of the world's population, also suffer from medium or high water scarcity and 17 of these extract more water annually than is recharged through their natural water cycles.[114] The strain not only affects surface freshwater bodies like rivers and lakes, but it also degrades groundwater resources.

Human uses

Agriculture

The most substantial human use of water is for agriculture, including irrigated agriculture, which accounts for as much as 80 to 90 percent of total human water consumption.[116] In the United States, 42% of freshwater withdrawn for use is for irrigation, but the vast majority of water "consumed" (used and not returned to the environment) goes to agriculture.[117]

Access to fresh water is often taken for granted, especially in developed countries that have built sophisticated water systems for collecting, purifying, and delivering water, and removing wastewater. But growing economic, demographic, and climatic pressures are increasing concerns about water issues, leading to increasing competition for fixed water resources, giving rise to the concept of peak water.[118] As populations and economies continue to grow, consumption of water-thirsty meat expands, and new demands rise for biofuels or new water-intensive industries, new water challenges are likely.[119]

An assessment of water management in agriculture was conducted in 2007 by the

Water scarcity is also caused by production of water intensive products. For example, cotton: 1 kg of cotton—equivalent of a pair of jeans—requires 10.9 cubic meters (380 cu ft) water to produce. While cotton accounts for 2.4% of world water use, the water is consumed in regions that are already at a risk of water shortage. Significant environmental damage has been caused: for example, the diversion of water by the former Soviet Union from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers to produce cotton was largely responsible for the disappearance of the Aral Sea.[122]

-

Water requirement per tonne of food product

-

Water distribution in subsurface drip irrigation

-

Irrigation of field crops

As a scientific standard

On 7 April 1795, the gram was defined in France to be equal to "the absolute weight of a volume of pure water equal to a cube of one-hundredth of a meter, and at the temperature of melting ice".[123] For practical purposes though, a metallic reference standard was required, one thousand times more massive, the kilogram. Work was therefore commissioned to determine precisely the mass of one liter of water. In spite of the fact that the decreed definition of the gram specified water at 0 °C (32 °F)—a highly reproducible temperature—the scientists chose to redefine the standard and to perform their measurements at the temperature of highest water density, which was measured at the time as 4 °C (39 °F).[124]

The

Natural water consists mainly of the isotopes hydrogen-1 and oxygen-16, but there is also a small quantity of heavier isotopes oxygen-18, oxygen-17, and hydrogen-2 (deuterium). The percentage of the heavier isotopes is very small, but it still affects the properties of water. Water from rivers and lakes tends to contain less heavy isotopes than seawater. Therefore, standard water is defined in the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water specification.

For drinking

The

Healthy kidneys can excrete 0.8 to 1 liter of water per hour, but stress such as exercise can reduce this amount. People can drink far more water than necessary while exercising, putting them at risk of water intoxication (hyperhydration), which can be fatal.[128][129] The popular claim that "a person should consume eight glasses of water per day" seems to have no real basis in science.[130] Studies have shown that extra water intake, especially up to 500 milliliters (18 imp fl oz; 17 U.S. fl oz) at mealtime, was associated with weight loss.[131][132][133][134][135][136] Adequate fluid intake is helpful in preventing constipation.[137]

An original recommendation for water intake in 1945 by the Food and Nutrition Board of the

Specifically, pregnant and breastfeeding women need additional fluids to stay hydrated. The US

Humans require water with few impurities. Common impurities include metal salts and oxides, including copper, iron, calcium and lead,

The single largest (by volume) freshwater resource suitable for drinking is Lake Baikal in Siberia.[143]

Washing

Washing is a method of cleaning, usually with water and soap or detergent. Washing and then rinsing both body and clothing is an essential part of good hygiene and health. [citation needed]

Often people use soaps and detergents to assist in the

People wash themselves, or bathe periodically for religious ritual or therapeutic purposes[144] or as a recreational activity.

In

More frequent is washing of just the hands, e.g. before and after preparing food and eating, after using the toilet, after handling something dirty, etc. Hand washing is important in reducing the spread of germs.[147][148] Also common is washing the face, which is done after waking up, or to keep oneself cool during the day. Brushing one's teeth is also essential for hygiene and is a part of washing.

'Washing' can also refer to the washing of clothing or other cloth items, like bedsheets, whether by hand or with a washing machine. It can also refer to washing one's car, by lathering the exterior with car soap, then rinsing it off with a hose, or washing cookware.

Transportation

Maritime transport can be realized over any distance by boat, ship, sailboat or

Chemical uses

Water is widely used in chemical reactions as a

Heat exchange

Water and steam are a common fluid used for

In the nuclear power industry, water can also be used as a neutron moderator. In most nuclear reactors, water is both a coolant and a moderator. This provides something of a passive safety measure, as removing the water from the reactor also slows the nuclear reaction down. However other methods are favored for stopping a reaction and it is preferred to keep the nuclear core covered with water so as to ensure adequate cooling.

Fire considerations

Water has a high heat of vaporization and is relatively inert, which makes it a good

Use of water in fire fighting should also take into account the hazards of a steam explosion, which may occur when water is used on very hot fires in confined spaces, and of a hydrogen explosion, when substances which react with water, such as certain metals or hot carbon such as coal, charcoal, or coke graphite, decompose the water, producing water gas.

The power of such explosions was seen in the Chernobyl disaster, although the water involved in this case did not come from fire-fighting but from the reactor's own water cooling system. A steam explosion occurred when the extreme overheating of the core caused water to flash into steam. A hydrogen explosion may have occurred as a result of a reaction between steam and hot zirconium.

Some metallic oxides, most notably those of

Recreation

Humans use water for many recreational purposes, as well as for exercising and for sports. Some of these include swimming,

Water industry

The

Drinking water is often collected at

The distribution of drinking water is done through

Reducing usage by using drinking (potable) water only for human consumption is another option. In some cities such as Hong Kong, seawater is extensively used for flushing toilets citywide in order to conserve freshwater resources.

Municipal and

-

A water-carrier in India, 1882. In many places where running water is not available, water has to be transported by people.

-

A manual water pump in China

-

Water purification facility

Industrial applications

Many industrial processes rely on reactions using chemicals dissolved in water, suspension of solids in water

Water is used in

Pressurized water is used in water blasting and water jet cutters. High pressure water guns are used for precise cutting. It works very well, is relatively safe, and is not harmful to the environment. It is also used in the cooling of machinery to prevent overheating, or prevent saw blades from overheating.

Water is also used in many industrial processes and machines, such as the steam turbine and heat exchanger, in addition to its use as a chemical solvent. Discharge of untreated water from industrial uses is pollution. Pollution includes discharged solutes (chemical pollution) and discharged coolant water (thermal pollution). Industry requires pure water for many applications and uses a variety of purification techniques both in water supply and discharge.

Food processing

Boiling, steaming, and simmering are popular cooking methods that often require immersing food in water or its gaseous state, steam.[154] Water is also used for dishwashing. Water also plays many critical roles within the field of food science.

Solutes in water also affect water activity that affects many chemical reactions and the growth of microbes in food.[156] Water activity can be described as a ratio of the vapor pressure of water in a solution to the vapor pressure of pure water.[155] Solutes in water lower water activity—this is important to know because most bacterial growth ceases at low levels of water activity.[156] Not only does microbial growth affect the safety of food, but also the preservation and shelf life of food.

According to a report published by the Water Footprint organization in 2010, a single kilogram of beef requires 15 thousand liters (3.3×103 imp gal; 4.0×103 U.S. gal) of water; however, the authors also make clear that this is a global average and circumstantial factors determine the amount of water used in beef production.[159]

Medical use

Distribution in nature

In the universe

Much of the universe's water is produced as a byproduct of star formation. The formation of stars is accompanied by a strong outward wind of gas and dust. When this outflow of material eventually impacts the surrounding gas, the shock waves that are created compress and heat the gas. The water observed is quickly produced in this warm dense gas.[162]

On 22 July 2011, a report described the discovery of a gigantic cloud of water vapor containing "140 trillion times more water than all of Earth's oceans combined" around a quasar located 12 billion light years from Earth. According to the researchers, the "discovery shows that water has been prevalent in the universe for nearly its entire existence".[163][164]

Water has been detected in interstellar clouds within the Milky Way.[165] Water probably exists in abundance in other galaxies, too, because its components, hydrogen, and oxygen, are among the most abundant elements in the universe. Based on models of the formation and evolution of the Solar System and that of other star systems, most other planetary systems are likely to have similar ingredients.

Water vapor

Water is present as vapor in:

- Atmosphere of the Sun: in detectable trace amounts[166]

- Atmosphere of Mercury: 3.4%, and large amounts of water in Mercury's exosphere[167]

- Atmosphere of Venus: 0.002%[168]

- Earth's atmosphere: ≈0.40% over full atmosphere, typically 1–4% at surface; as well as that of the Moon in trace amounts[169]

- Atmosphere of Mars: 0.03%[170]

- Atmosphere of Ceres[171]

- Atmosphere of Jupiter: 0.0004%[172] – in ices only; and that of its moon Europa[173]

- ]

- Atmosphere of Uranus – in trace amounts below 50 bar

- Atmosphere of Neptune – found in the deeper layers[175]

- Extrasolar planet atmospheres: including those of HD 189733 b[176] and HD 209458 b,[177] Tau Boötis b,[178] HAT-P-11b,[179][180] XO-1b, WASP-12b, WASP-17b, and WASP-19b.[181]

- Stellar atmospheres: not limited to cooler stars and even detected in giant hot stars such as Betelgeuse, Mu Cephei, Antares and Arcturus.[180][182]

Liquid water

Liquid water is present on Earth, covering 71% of its surface.

Water ice

Water is present as ice on:

- Mars: under the regolith and at the poles.[192][193]

- Earth–Moon system: mainly as ice sheets on Earth and in Lunar craters and volcanic rocks[194] NASA reported the detection of water molecules by NASA's Moon Mineralogy Mapper aboard the Indian Space Research Organization's Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft in September 2009.[195]

- Ceres[196][197][198]

- Jupiter's moons: Europa's surface and also that of Ganymede[199] and Callisto[200][201]

- Saturn: in the Enceladus[204]

- Pluto–Charon system[202]

And is also likely present on:

Exotic forms

Water and other

Water and planetary habitability

The existence of liquid water, and to a lesser extent its gaseous and solid forms, on Earth are vital to the existence of life on Earth as we know it. The Earth is located in the habitable zone of the Solar System; if it were slightly closer to or farther from the Sun (about 5%, or about 8 million kilometers), the conditions which allow the three forms to be present simultaneously would be far less likely to exist.[211][212]

Earth's

The surface temperature of Earth has been relatively constant through

The state of water on a planet depends on ambient pressure, which is determined by the planet's gravity. If a planet is sufficiently massive, the water on it may be solid even at high temperatures, because of the high pressure caused by gravity, as it was observed on exoplanets Gliese 436 b[213] and GJ 1214 b.[214]

Law, politics, and crisis

This section needs to be updated. (June 2022) |

Water politics is politics affected by water and water resources. Water, particularly fresh water, is a strategic resource across the world and an important element in many political conflicts. It causes health impacts and damage to biodiversity.

Access to safe drinking water has improved over the last decades in almost every part of the world, but approximately one billion people still lack access to safe water and over 2.5 billion lack access to adequate sanitation.[215] However, some observers have estimated that by 2025 more than half of the world population will be facing water-based vulnerability.[216] A report, issued in November 2009, suggests that by 2030, in some developing regions of the world, water demand will exceed supply by 50%.[217]

1.6 billion people have gained access to a safe water source since 1990.[218] The proportion of people in developing countries with access to safe water is calculated to have improved from 30% in 1970[219] to 71% in 1990, 79% in 2000, and 84% in 2004.[215]

A 2006 United Nations report stated that "there is enough water for everyone", but that access to it is hampered by mismanagement and corruption.

The authors of the 2007 Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture cited poor governance as one reason for some forms of water scarcity. Water governance is the set of formal and informal processes through which decisions related to water management are made. Good water governance is primarily about knowing what processes work best in a particular physical and socioeconomic context. Mistakes have sometimes been made by trying to apply 'blueprints' that work in the developed world to developing world locations and contexts. The Mekong river is one example; a review by the International Water Management Institute of policies in six countries that rely on the Mekong river for water found that thorough and transparent cost-benefit analyses and environmental impact assessments were rarely undertaken. They also discovered that Cambodia's draft water law was much more complex than it needed to be.[222]

In 2004, the UK charity WaterAid reported that a child dies every 15 seconds from easily preventable water-related diseases, which are often tied to a lack of adequate sanitation.[223][224]

Since 2003, the

Organizations concerned with water protection include the

In culture

Religion

Water is considered a purifier in most religions. Faiths that incorporate ritual washing (

In Christianity,

In Zoroastrianism, water (āb) is respected as the source of life.[234]

Philosophy

The Ancient Greek philosopher

The theory of the

Some traditional and popular

Folklore

"Living water" features in Germanic and Slavic folktales as a means of bringing the dead back to life. Note the Grimm fairy-tale ("The Water of Life") and the Russian dichotomy of living and dead water. The Fountain of Youth represents a related concept of magical waters allegedly preventing aging.

Art and activism

Painter and activist

To mark the 10th anniversary of access to water and sanitation being declared a human right by the UN, the charity WaterAid commissioned ten visual artists to show the impact of clean water on people's lives.[247][248]

Dihydrogen monoxide parody

'Dihydrogen monoxide' is a technically correct but rarely used

Music

The word "Water" has been used by many Florida based rappers as a sort of catchphrase or adlib. Rappers who have done this include BLP Kosher and Ski Mask the Slump God.[250] To go even further some rappers have made whole songs dedicated to the water in Florida, such as the 2023 Danny Towers song "Florida Water".[251] Others have made whole songs dedicated to water as a whole, such as XXXTentacion, and Ski Mask the Slump God with their hit song "H2O".

See also

- Outline of water – Overview of and topical guide to water

- Water (data page) – Chemical data page for water is a collection of the chemical and physical properties of water.

- Aquaphobia – Persistent and abnormal fear of water

- Human right to water and sanitation – Human right recognized by the United Nations General Assembly in 2010

- Hydroelectricity – Electricity generated by hydropower

- Marine current power – Extraction of power from ocean currents

- Marine energy – Energy stored in the waters of oceans

- Mpemba effect – Natural phenomenon that hot water freezes faster than cold

- Oral rehydration therapy – Type of fluid replacement used to prevent and treat dehydration

- Osmotic power – Energy available from the difference in the salt concentration between seawater and river water

- Properties of water – Physical and chemical properties of pure water

- Thirst – Craving for potable fluids experienced by animals

- Tidal power – Technology to convert the energy from tides into useful forms of power

- Water pinch analysis

- Wave power – Transport of energy by wind waves, and the capture of that energy to do useful work

- Catchwater – Runoff catching or channeling device

Notes

- ^ A commonly quoted value of 15.7 used mainly in organic chemistry for the pKa of water is incorrect.[11][12]

- ^ a b Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), used for calibration, melts at 273.1500089(10) K (0.000089(10) °C, and boils at 373.1339 K (99.9839 °C). Other isotopic compositions melt or boil at slightly different temperatures.

- ^ see the taste and odor section

- ^ Other substances with this property include bismuth, silicon, germanium and gallium.[51]

References

- ^ "naming molecular compounds". www.iun.edu. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

Sometimes these compounds have generic or common names (e.g., H2O is "water") and they also have systematic names (e.g., H2O, dihydrogen monoxide).

- ^ "Definition of Hydrol". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ .

- doi:10.18434/T4D303. Archivedfrom the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ Lide 2003, Properties of Ice and Supercooled Water in Section 6.

- ^ a b c Anatolievich KR. "Properties of substance: water". Archived from the original on 2 June 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2014.

- ^ Lide 2003, Vapor Pressure of Water From 0 to 370 °C in Sec. 6.

- ^ Lide 2003, Chapter 8: Dissociation Constants of Inorganic Acids and Bases.

- ^ Weingärtner et al. 2016, p. 13.

- ^ "What is the pKa of Water". University of California, Davis. 9 August 2015. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- .

- ISSN 0047-2689.

- ^ Lide 2003, 8—Concentrative Properties of Aqueous Solutions: Density, Refractive Index, Freezing Point Depression, and Viscosity.

- ^ Lide 2003, 6.186.

- ^ a b c d Water in Linstrom, Peter J.; Mallard, William G. (eds.); NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg (MD)

- ^ Lide 2003, 9—Dipole Moments.

- ^ GHS: PubChem 962 Archived 2023-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- U.S. Department of the Interior. 20 June 2019. Archivedfrom the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ "10.2: Hybrid Orbitals in Water". Chemistry LibreTexts. 18 March 2020. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ Butler J. "The Earth – Introduction – Weathering". University of Houston. Archived from the original on 30 January 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

Note that the Earth environment is close to the triple point and that water, steam and ice can all exist at the surface.

- ^ U.S. Department of the Interior. 13 November 2019. Archivedfrom the original on 9 June 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2022.

- ^ a b Gleick, P.H., ed. (1993). Water in Crisis: A Guide to the World's Freshwater Resources. Oxford University Press. p. 13, Table 2.1 "Water reserves on the earth". Archived from the original on 8 April 2013.

- UNEP.

- PMID 17035955.

- PMID 25136111.

- ^ "Water (v.)". www.etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ISSN 0019-1035.

- S2CID 119079927.

- S2CID 4413525.

- S2CID 6909122.

- PMID 11259665.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-642-27833-4

- ISSN 0012-821X.

- ISSN 0301-9268.

- S2CID 221342529. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- EurekAlert!. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- EurekAlert!. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- S2CID 4319774.

- ^ "ANU - Research School of Earth Sciences - ANU College of Science - Harrison". Ses.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 21 June 2006. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "ANU - OVC - MEDIA - MEDIA RELEASES - 2005 - NOVEMBER - 181105HARRISONCONTINENTS". Info.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "A Cool Early Earth". Geology.wisc.edu. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ Chang K (2 December 2008). "A New Picture of the Early Earth". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- USGS. Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-321-77565-8.

- ISBN 978-0-321-77565-8.

- OCLC 37341352. Archived from the original(PDF) on 26 July 2011.

- ^ PubChem. "Water". National Center for Biotechnology Information. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ a b Belnay L. "The water cycle" (PDF). Critical thinking activities. Earth System Research Laboratory. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-662-53207-2. Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "What is Density?". Mettler Toledo. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- ^ from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-534-39597-1.

- ISBN 978-981-4338-96-7.

- S2CID 131395533.

- ^ Wiltse B. "A Look Under The Ice: Winter Lake Ecology". Ausable River Association. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- ^ hdl:11299/90865. Archivedfrom the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ Wells S (21 January 2017). "The Beauty and Science of Snowflakes". Smithsonian Science Education Center. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- OCLC 960758611.

- S2CID 4423510.

- ^ Davies B. "Antarctic subglacial lakes". AntarcticGlaciers. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-495-12671-3. Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Peaco J. "Yellowstone Lesson Plan: How Yellowstone Geysers Erupt". Yellowstone National Park: U.S. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Brahic C. "Found: The hottest water on Earth". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. "High Altitude Cooking and Food Safety" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Pressure Cooking – Food Science". Exploratorium. 26 September 2019. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Allain R (12 September 2018). "Yes, You Can Boil Water at Room Temperature. Here's How". Wired. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ISBN 92-822-2213-6. Archived(PDF) from the original on 14 August 2017.

- ^ "9th edition of the SI Brochure". BIPM. 2019. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- .

- PMID 15827975.

- .

- S2CID 4427815.

- PMID 30770019.

- ^ Sokol J (12 May 2019). "A Bizarre Form of Water May Exist All Over the Universe". Wired. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- S2CID 138877465.

- (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2023. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- PMID 23251779.

- PMID 28652327.

- from the original on 5 March 2024. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ISBN 978-0198570035.

- ISBN 978-3642663161

- from the original on 2 October 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ISBN 0-471-16394-5.

- ^ Ball 2001, p. 168

- ^ Franks 2007, p. 10

- ^ "Physical Chemistry of Water". Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ Ball 2001, p. 169

- .

- ISBN 978-0-13-250882-7. Archivedfrom the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "Heat capacity water online". Desmos (in Russian). Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2022.

- from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- .

- ^ UK National Physical Laboratory, Calculation of absorption of sound in seawater Archived 3 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Online site, last accessed on 28 September 2016.

- ^ Gleick PH, ed. (1993). Water in Crisis: A Guide to the World's Freshwater Resources. Oxford University Press. p. 15, Table 2.3. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013.

- ISBN 978-981-4338-96-7.

- ^ "water resource". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- ISBN 0-19-507627-3.

- .

- ^ "Catalyst helps split water: Plants". AskNature. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ISBN 0-521-64497-6. Archivedfrom the original on 5 October 2023. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

- ^ "On Water". European Investment Bank. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Jammi R (13 March 2018). "2.4 billion Without Adequate Sanitation. 600 million Without Safe Water. Can We Fix it by 2030?". World Bank Group. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ "Wastewater resource recovery can fix water insecurity and cut carbon emissions". European Investment Bank. Archived from the original on 29 August 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ "International Decade for Action 'Water for Life' 2005–2015. Focus Areas: Water scarcity". United Nations. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ "The State of the World's Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ "World Health Organization. Safe Water and Global Health". World Health Organization. 25 June 2008. Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- OCLC 49204666.

- OCLC 231965991.

- ^ "Water withdrawals per capita". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ "WBCSD Water Facts & Trends". Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- doi:10.3133/cir1441. Archivedfrom the original on 28 April 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ United Nations Press Release POP/952 (13 March 2007). "World population will increase by 2.5 billion by 2050". Archived 27 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- A Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture. Earthscan/IWMI, 2007.

- ^ Chartres, C. and Varma, S. (2010) Out of water. From Abundance to Scarcity and How to Solve the World's Water Problems. FT Press (US).

- ^ Chapagain AK, Hoekstra AY, Savenije HH, Guatam R (September 2005). "The Water Footprint of Cotton Consumption" (PDF). IHE Delft Institute for Water Education. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- germinal an 3 (7 April 1795). Archived 25 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. quartier-rural.org

- ^ here "L'Histoire Du Mètre, La Détermination De L'Unité De Poids" Archived 25 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. histoire.du.metre.free.fr

- ^ "Re: What percentage of the human body is composed of water?" Archived 25 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine Jeffrey Utz, M.D., The MadSci Network

- ^ "Healthy Water Living". BBC Health. Archived from the original on 1 January 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2007.

- OCLC 50554808.

- PMID 4021781.

- S2CID 28370290.

- S2CID 2256436. Archived from the original(PDF) on 22 February 2019.

- S2CID 24899383.

- ^ "Drink water to curb weight gain? Clinical trial confirms effectiveness of simple appetite control method". Science Daily. 23 August 2010. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- S2CID 27561994.

- PMID 19661958.

- PMID 24179891.

- S2CID 12265434.

- ^ "Water, Constipation, Dehydration, and Other Fluids". Archived 4 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Science Daily. Retrieved on 28 September 2015.

- ^ Food and Nutrition Board, National Academy of Sciences. Recommended Dietary Allowances. National Research Council, Reprint and Circular Series, No. 122. 1945. pp. 3–18.

- ISBN 978-0-309-09169-5. Archivedfrom the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- ^ "Water: How much should you drink every day?". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ Conquering Chemistry (4th ed.), 2008

- OCLC 32308337.

- ISBN 978-1-84545-177-6.

- ISBN 978-1-85973-630-2.

- ^ "Eco-Friendly Cleaning Cloth and Toilet Papers". SimplyNatural. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ISBN 9780721625973.

Douching is commonly practiced in Catholic countries. The bidet ... is still commonly found in France and other Catholic countries.

- ^ CDC: Why Wash Your Hands?

- ^ Clean Hands, Thomas Osborne, M.D.

- ^ You Probably Wash Your Hair Way Too Much retrieved 6 October 2012

- ^ Infections in Obstetrics and Gynecology: Textbook and Atlas retrieved 6 October 2012, Eiko Petersen - pages 6–13

- ISBN 9780415153102.

- ^ "Water Use in the United States", National Atlas. Archived 14 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Material Safety Data Sheet: Quicklime" (PDF). Lhoist North America. 6 August 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ Duff LB (1916). A Course in Household Arts: Part I. Whitcomb & Barrows. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-387-69939-4. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8342-1234-3. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Map showing the rate of hardness in mg/L as Calcium carbonate in England and Wales" (PDF). DEFRA Drinking Water Inspectorate. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Water hardness". US Geological Service. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY (December 2010). The green, blue and grey water footprint of farm animals and animal products, Value of Water (PDF) (Report). Research Report Series. Vol. 1. UNESCO – IHE Institute for Water Education. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ "ALMA Greatly Improves Capacity to Search for Water in Universe". Archived from the original on 23 July 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and Neufeld, David, Johns Hopkins Universityquoted in: "Discover of Water Vapor Near Orion Nebula Suggests Possible Origin of H20 in Solar System (sic)". The Harvard University Gazette. 23 April 1998. Archived from the original on 16 January 2000. "Space Cloud Holds Enough Water to Fill Earth's Oceans 1 Million Times". Headlines@Hopkins, JHU. 9 April 1998. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 21 April 2007. "Water, Water Everywhere: Radio telescope finds water is common in universe". The Harvard University Gazette. 25 February 1999. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 19 September 2010. (archive link)

- ^ a b Clavin W, Buis A (22 July 2011). "Astronomers Find Largest, Most Distant Reservoir of Water". NASA. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2011.

- ^ a b Staff (22 July 2011). "Astronomers Find Largest, Oldest Mass of Water in Universe". Space.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- ISBN 978-0-06-185448-4. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- S2CID 27696504. Archived from the original(PDF) on 7 March 2019.

- ^ "MESSENGER Scientists 'Astonished' to Find Water in Mercury's Thin Atmosphere". Planetary Society. 3 July 2008. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- (PDF) from the original on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- .

- ISBN 978-3-642-32762-9. Archivedfrom the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- S2CID 4448395.

- (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Cook JR, Gutro R, Brown D, Harrington J, Fohn J (12 December 2013). "Hubble Sees Evidence of Water Vapor at Jupiter Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- S2CID 2954801. Archived from the original(PDF) on 18 February 2020.

- S2CID 36248590.

- ^ Water Found on Distant Planet Archived 16 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine 12 July 2007 By Laura Blue, Time

- ^ Water Found in Extrasolar Planet's Atmosphere Archived 30 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine – Space.com

- S2CID 8463125.

- ^ Clavin W, Chou F, Weaver D, Villard, Johnson M (24 September 2014). "NASA Telescopes Find Clear Skies and Water Vapor on Exoplanet". NASA. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-481-9984-6. Archivedfrom the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ "Hubble Traces Subtle Signals of Water on Hazy Worlds". NASA. 3 December 2013. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ a b Andersson, Jonas (June 2012). Water in stellar atmospheres "Is a novel picture required to explain the atmospheric behavior of water in red giant stars?" Archived 13 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine Lund Observatory, Lund University, Sweden

- ^ Herschel Finds Oceans of Water in Disk of Nearby Star Archived 19 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Nasa.gov (20 October 2011). Retrieved on 28 September 2015.

- ^ "JPL". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Archived from the original on 4 June 2012.

- ^ Lloyd, Robin. "Water Vapor, Possible Comets, Found Orbiting Star", 11 July 2001, Space.com. Retrieved 15 December 2006. Archived 23 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NASA Confirms Evidence That Liquid Water Flows on Today's Mars". NASA. 28 September 2015. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Platt J, Bell B (3 April 2014). "NASA Space Assets Detect Ocean inside Saturn Moon". NASA. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Bibcode:2013LPI....44.2454D. Archived(PDF) from the original on 23 March 2014. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Tritt CS (2002). "Possibility of Life on Europa". Milwaukee School of Engineering. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2007.

- ^ Dunham, Will. (3 May 2014) Jupiter's moon Ganymede may have 'club sandwich' layers of ocean | Reuters Archived 3 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine. In.reuters.com. Retrieved on 28 September 2015.

- ^ Carr M (1996). Water on Mars. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 197.

- S2CID 4373206.

- ^ Versteckt in Glasperlen: Auf dem Mond gibt es Wasser – Wissenschaft – Archived 10 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine Der Spiegel – Nachrichten

- ^ Water Molecules Found on the Moon Archived 27 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, NASA, 24 September 2009

- (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- S2CID 17758979.

- ^ Carey B (7 September 2005). "Largest Asteroid Might Contain More Fresh Water than Earth". SPACE.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2006.

- New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- .

- S2CID 9492520. Archived from the original(PDF) on 12 April 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-59223-579-7.

- .

- S2CID 21932253. (supporting online material, table S1)

- Bibcode:1998A&A...330..375G.

- ^ "Dirty Snowballs in Space". Starryskies. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- .

- ^ NASA, "MESSENGER Finds New Evidence for Water Ice at Mercury's Poles Archived 30 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine", NASA, 29 November 2012.

- (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Weird water lurking inside giant planets Archived 15 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, New Scientist, 1 September 2010, Magazine issue 2776.

- ^ Ehlers, E., Krafft, T, eds. (2001). "J.C.I. Dooge. "Integrated Management of Water Resources"". Understanding the Earth System: compartments, processes, and interactions. Springer. p. 116.

- ^ "Habitable Zone". The Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy and Spaceflight. Archived from the original on 23 May 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2007.

- ^ Shiga D (6 May 2007). "Strange alien world made of "hot ice"". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ Aguilar, David A. (16 December 2009). "Astronomers Find Super-Earth Using Amateur, Off-the-Shelf Technology". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ a b "MDG Report 2008" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- S2CID 152322295.

- ^ "Charting Our Water Future: Economic frameworks to inform decision-making" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "The Millennium Development Goals Report". Archived 27 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations, 2008

- ISBN 978-0-521-01068-9. Archived from the original(PDF) on 25 July 2013.

- ^ UNESCO, (2006), "Water, a shared responsibility. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2". Archived 6 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Welle, Katharina; Evans, Barbara; Tucker, Josephine; and Nicol, Alan (2008). "Is water lagging behind on Aid Effectiveness?" Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Search Results". International Water Management Institute (IWMI). Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ Burrows G (24 March 2004). "Clean water to fight poverty". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 February 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ a b c "Home | UN World Water Development Report 2023". www.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "UN World Water Development Report 2023". www.rural21.com. 29 March 2023. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "UN warns 'vampiric' water use leading to 'imminent' global crisis". France 24. 22 March 2023. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "New UN report paints stark picture of huge changes needed to deliver safe drinking water to all people". ABC News. 22 March 2023. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "World Water Day". United Nations. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "About". World Oceans Day Online Portal. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-61168-955-6.

Water plays a role in other Christian rituals as well. ... In the early days of Christianity, two to three centuries after Christ, the lavabo (Latin for "I wash myself"), a ritual handwashing vessel and bowl, was introduced as part of Church service.

- ^ Chambers's encyclopædia, Lippincott & Co (1870). p. 394.

- ISBN 1-58768-013-0.

- Encyclopedia Iranica. Archivedfrom the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Lindberg, D. (2008). The beginnings of western science: The European scientific tradition in a philosophical, religious, and institutional context, prehistory to A.D. 1450 (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Tao Te Ching. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010 – via Internet Sacred Text Archive Home.

- ^ "Guanzi : Shui Di". Chinese Text Project. Archived 6 November 2014 at archive.today. Retrieved on 28 September 2015.

- ^ Vartanian H (3 October 2011). "Manhattan Cathedral Explores Water in Art". Hyperallergic. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Kowalski JA (6 October 2011). "The Cathedral of St. John the Divine and The Value of Water". huffingtonpost.com. Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 6 August 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Foster F. "The Value of Water at St John the Divine". vimeo.com. Sara Karl. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Miller T. "The Value of Water Exhibition". UCLA Art Science Center. Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Madel R (6 December 2017). "Through Art, the Value of Water Expressed". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Cotter M (4 October 2011). "Manhattan Cathedral Examines 'The Value of Water' in a New Star-Studded Art Exhibition". Inhabitat. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Think About Water". Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Basia Irland". Archived from the original on 14 October 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "Influential Figures Dr. Charlotte Cote". Tseshaht First Nation [c̓išaaʔatḥ]. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "10 years of the human rights to water and sanitation". United Nations. UN – Water Family News. 27 February 2020. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "Water is sacred': 10 visual artists reflect on the human right to water". The Guardian. 4 August 2020. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "dihydrogen monoxide". March 2018. Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "What Does Water Mean In Rap? (EXPLAINED)". Lets Learn Slang. 27 December 2021. Archived from the original on 6 August 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ Danny Towers, DJ Scheme & Ski Mask the Slump God (Ft. Luh Tyler) – Florida Water, archived from the original on 6 August 2023, retrieved 6 August 2023

Works cited

- Ball P (2001). Life's matrix : a biography of water. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-520-23008-8.

- Franks F (2007). Water : a matrix of life (2nd ed.). Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84755-234-1.

- Lide DR (2003). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. ISBN 978-0-8493-0484-2. Archivedfrom the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- Weingärtner H, Teermann I, Borchers U, Balsaa P, Lutze HV, Schmidt TC, et al. (2016). "Water, 1. Properties, Analysis, and Hydrological Cycle". ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

Further reading

- Debenedetti, PG., and HE Stanley, "Supercooled and Glassy Water", Physics Today 56 (6), pp. 40–46 (2003). Downloadable PDF (1.9 MB) Archived 1 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Gleick, PH., (editor), The World's Water: The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources. Island Press, Washington, D.C. (published every two years, beginning in 1998.) The World's Water, Island Press Archived 26 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Jones OA, Lester JN, Voulvoulis N (2005). "Pharmaceuticals: a threat to drinking water?". Trends in Biotechnology. 23 (4): 163–167. PMID 15780706.

- Journal of Contemporary Water Research & Education Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Postel, S., Last Oasis: Facing Water Scarcity. W.W. Norton and Company, New York. 1992

- Reisner, M., Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its Disappearing Water. Penguin Books, New York. 1986.

- United Nations World Water Development Report Archived 22 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Produced every three years.

- St. Fleur, Nicholas. The Water in Your Glass Might Be Older Than the Sun Archived 15 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. "The water you drink is older than the planet you're standing on." The New York Times (15 April 2016)

External links

- The World's Water Data Page

- FAO Comprehensive Water Database, AQUASTAT

- The Water Conflict Chronology: Water Conflict Database Archived 16 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Water science school (USGS)

- Portal to The World Bank's strategy, work and associated publications on water resources

- America Water Resources Association Archived 24 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Water on the web

- Water structure and science Archived 28 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Why water is one of the weirdest things in the universe", Ideas, BBC, Video, 3:16 minutes, 2019

- The chemistry of water Archived 19 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine (NSF special report)

- The International Association for the Properties of Water and Steam

- H2O: The Molecule That Made Us, a 2020 PBS documentary