HMS Erin

Erin in the Moray Firth, August 1915

| |

| Name | Reşad V |

| Namesake | Sultan Mehmed V |

| Ordered | 8 June 1911 |

| Builder | Vickers |

| Yard number | 425 |

| Laid down | 6 December 1911 |

| Launched | 3 September 1913 |

| Renamed | Reşadiye |

| Fate | Seized, 31 July 1914 |

| Name | Erin |

| Namesake | Erin |

| Completed | August 1914 |

| Decommissioned | May 1922 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 19 December 1922 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 559 ft 6 in (170.54 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 91 ft 7 in (27.9 m) |

| Draught | 28 ft 5 in (8.7 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 4 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 5,300 nmi (9,800 km; 6,100 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS Erin was a

Aside from a minor role in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 and the inconclusive Action of 19 August the same year, Erin's service during the war generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea. The ship was deemed obsolete after the war; she was reduced to reserve and used as a training ship. Erin served as the flagship of the reserve fleet at the Nore for most of 1920. She was sold for scrap in 1922 and broken up the following year.

Design and description

The design of the Reşadiye class was based on the

Erin was powered by a pair of

Armament and armour

The ship was armed with a

Wartime modifications

Four of the six-pounder guns were removed in 1915–1916, and a

Construction and career

Erin originally was ordered by the

The takeover caused considerable ill will in the Ottoman Empire, where public subscriptions had partially funded the ships. When the Ottoman government had been in a financial deadlock over the budget of the battleships, donations for the Ottoman Navy had come in from taverns, cafés, schools and markets, and large donations were rewarded with a "Navy Donation Medal". The seizure, and the gift of the German

1914–1915

Jellicoe's ships, including Erin, practised gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of the Orkney and

The Grand Fleet conducted sweeps into the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering German vessels. During 11–14 June, the fleet practised gunnery and battle exercises off Shetland from 11 July.

1916–1918

The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February 1916; Jellicoe had intended to use the

Battle of Jutland

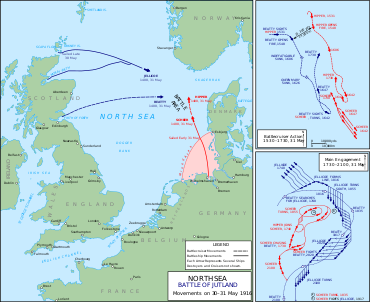

To lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet (Admiral

During the Battle of Jutland on 31 May, Beatty's battlecruisers managed to bait Scheer and Hipper into a pursuit as they fell back upon the main body of the Grand Fleet. After Jellicoe deployed his ships into line of battle, Erin was the fourth from the head of the line.[35] Scheer's manoeuvres after spotting the Grand Fleet were generally away from Jellicoe's leading ships, and the poor visibility hindered their ability to close with the Germans before Scheer could disengage under the cover of darkness. Opportunities to shoot during the battle were rare, and she only fired 6 six-inch shells from her secondary armament. Erin was the only British battleship not to fire her main guns during the battle.[36]

Subsequent activity

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boats during the operation, prompting Jellicoe to decide to not risk the major units of the fleet south of 55° 30' North due to the prevalence of German submarines and mines. The Admiralty concurred and stipulated that the Grand Fleet would not sortie unless the German fleet was attempting an invasion of Britain or that it could be forced into an engagement at a disadvantage.

In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet sortied against British convoys to Norway. Wireless silence was enforced, which prevented Room 40 cryptanalysts from warning the new commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty. The British only learned of the operation after an accident aboard the battlecruiser SMS Moltke forced her to break radio silence and inform the German commander of her condition. Beatty ordered the Grand Fleet to sea to intercept the Germans, but he was not able to reach the High Seas Fleet before it turned back for Germany.[40] The ship was at Rosyth, Scotland, when the surrendered High Seas Fleet arrived on 21 November and she remained part of the 2nd BS through 1 March 1919.[41][42]

Postwar

Captain

Notes

- ^ Sources disagree on the number of each model of gun mounted on the ship, although everyone agrees that most of the guns fitted were Mk VI guns. Friedman claims that two Mk V guns were mounted and that doing so expedited the completion of the ship. Campbell says that she carried a Mk V gun for a time. Campbell and Friedman state the Mk V guns aboard Erin were provided with reduced powder charges to match the ballistic trajectories of the Mk VI guns.[4] Preston says that they were all Mk VI guns, while Parkes and Silverstone do not identify the exact types.[2][5]

- ^ "Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 20 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

- ^ Sources disagree regarding the initial name of the ship. Langensiepen and Güleryüz, in their history of the Ottoman Navy, state that her only name prior to the British seizure was Reşadiye and Silverstone agrees with them.[13][10]

- ^ In his 1919 book, Jellicoe generally named ships only when they were undertaking individual actions. Usually he referred to the Grand Fleet or by squadrons. Unless otherwise specified, this article assumes that Erin is participating in the activities of the Grand Fleet.[23]

Citations

- ^ Burt, p. 245

- ^ a b c d Preston, p. 36

- ^ a b Burt, p. 248

- ^ Friedman, p. 52; Campbell 1981, p. 97

- ^ Parkes, p. 597; Silverstone, pp. 192, 405

- ^ Burt, pp. 247–248, 252

- ^ Burt, pp. 252–253

- ^ Brooks, p. 168

- ^ Burt, pp. 253, 256

- ^ a b c Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 141

- ^ a b c d e f Burt, p. 256

- ^ Parkes, p. 599

- ^ a b Silverstone, p. 409

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 29

- ^ Hastings, p. 115

- ^ Silverstone, p. 230

- ^ Fromkin, pp. 56–57

- ^ Hough, pp. 143–144

- ^ Fromkin, pp. 68—72

- ^ Fromkin, pp. 58–61, 67–72

- His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1914. p. 312. Archivedfrom the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 129–133

- ^ Jellicoe, p. 129

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 135–137, 143, 156, 158, 163–165, 179, 182–184

- ^ Jellicoe, p. 190

- ^ Monograph No. 12, p. 224

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 194–196, 206, 211–212

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 217–219, 221–222

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 228, 243, 246, 250, 253

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. September 1915. p. 10. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. December 1915. p. 10. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 271, 275, 279–280

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 284, 286–290

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- ^ Corbett, frontispiece map and p. 428

- ^ Campbell 1986, pp. 96, 148, 197–198, 248, 273–274, 346, 358

- ^ Halpern, pp. 330–332

- ^ "Victor Albert Stanley". The Dreadnought Project. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1918. p. 788. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 418–420

- ^ "Operation ZZ". The Dreadnought Project. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. London: Admiralty. 1 March 1919. p. 10. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1919. p. 770. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. 1 May 1919. p. 5. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1919. p. 709. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. January 1920. pp. 707, 770. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 November 1919. p. 770. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. October 1920. pp. 695–6. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Navy List". National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 December 1920. pp. 695–6, 770–1. Retrieved 17 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

References

- Brooks, John (1996). "Percy Scott and the Director". In McLean, David & Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 150–170. ISBN 0-85177-685-X.

- Burt, R. A. (2012) [1986]. British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-053-5.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1981). "British Naval Guns 1880–1945, Number Two". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship V. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 0-85177-244-7.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- ISBN 1-870423-50-X.

- ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8050-0857-9.

- ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- ISBN 978-0-307-59705-2.

- OCLC 914101.

- OCLC 13614571.

- Langensiepen, Bernd & Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy, 1828–1923. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-610-8.

- Monograph No. 12: The Action of Dogger Bank–24th January 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. III. The Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division. 1921. pp. 209–226. OCLC 220734221– via Royal Australian Navy.

- ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.