HMS King George V (1911)

A postcard of King George V underway, about 1913

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | King George V |

| Namesake | King George V |

| Builder | HM Dockyard, Portsmouth |

| Cost | £1,961,096 |

| Laid down | 16 January 1911 |

| Launched | 9 October 1911 |

| Commissioned | 16 November 1912 |

| Decommissioned | 26 October 1926 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, December 1926 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 25,420 long tons (25,830 t) (normal) |

| Length | 594 ft 4 in (181.2 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 89 ft 1 in (27.2 m) |

| Draught | 28 ft 8 in (8.7 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 5,910 nmi (10,950 km; 6,800 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 869–1,114 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS King George V was the

After the war, King George V became flagship of the Home Fleet and then of the

Design and description

The King George V-class ships were designed as enlarged and improved versions of the preceding

The ships of the King George V class were powered by two sets of

Armament and armour

Like the Orion class, the King George Vs were equipped with 10

The King George V-class ships were protected by a

Modifications

A

Construction and career

King George V, named after the reigning

First World War

Between 17 and 20 July 1914, King George V took part in a test

Bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby

The Royal Navy's

The screening forces of each side blundered into each other during the early morning darkness of 16 December in heavy weather. The Germans got the better of the initial exchange of fire, severely damaging several British destroyers, but von Ingenohl, commander of the High Seas Fleet, ordered his ships to turn away, concerned about the possibility of a massed attack by British destroyers in the dawn's light. A series of miscommunications and mistakes by the British allowed Hipper's ships to avoid an engagement with Beatty's forces.[20]

1915–1916

Retubing of the ship's starboard condenser took from late December to 4 January 1915. Jellicoe's ships, including King George V, conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January west of the

The Grand Fleet conducted sweeps into the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering any German vessels. During 11–14 June, the fleet conducted gunnery practice and battle exercises west of Shetland[22] and more training off Shetland beginning on 11 July. The 2nd BS conducted gunnery practice in the Moray Firth on 2 August and then returned to Scapa Flow. On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea and conducted gunnery drills. Throughout the rest of the month, the Grand Fleet conducted numerous training exercises. The ship, together with the majority of the Grand Fleet, conducted another sweep into the North Sea from 13 to 15 October. Almost three weeks later, King George V participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney during 2–5 November and repeated the exercise at the beginning of December.[23] Warrender was relieved by Vice-Admiral Sir Martyn Jerram on 16 December.[24]

The Grand Fleet sortied in response to an attack by German ships on British light forces near Dogger Bank on 10 February 1916, but it was recalled two days later when it became clear that no German ships larger than a destroyer were involved. The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February; Jellicoe had intended to use the

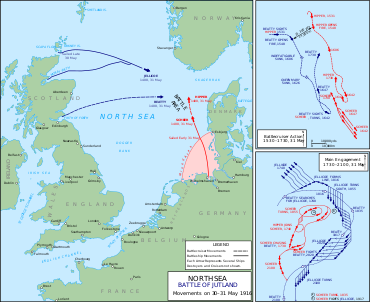

Battle of Jutland

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the High Seas Fleet, composed of sixteen dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts and supporting ships, departed the Jade Bight early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Hipper's five battlecruisers. Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[27]

On 31 May, King George V, under the command of

Subsequent activity

The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German

In April 1918, the High Seas Fleet again sortied, to attack British convoys to Norway. They enforced strict wireless silence during the operation, which prevented Room 40 cryptanalysts from warning the new commander of the Grand Fleet, Admiral Beatty. The British only learned of the operation after an accident aboard the battlecruiser SMS Moltke forced her to break radio silence to inform the German commander of her condition. Beatty then ordered the Grand Fleet to sea to intercept the Germans, but he was not able to reach the High Seas Fleet before it turned back for Germany.[32] The ship was present at Rosyth, Scotland, when the High Seas Fleet surrendered there on 21 November[33] and she remained part of the 2nd Battle Squadron through 1 March 1919.[34]

Postwar activities

By 1 May, King George V had been assigned to the

King George V recommissioned on 31 October and sailed for the Mediterranean. In February 1921, together with the dreadnought

In January 1923, the ship returned home and became a gunnery training ship at

Notes

Citations

- ^ Burt, pp. 169–70

- ^ a b c Burt, p. 176

- ^ Parkes, p. 538

- ^ Burt, pp. 176, 179

- ^ Burt, pp. 175–76

- ^ Brooks, p. 168; Burt, p. 170

- ^ Friedman, p. 199

- ^ Burt, pp. 170, 179–80

- ^ Silverstone, p. 247

- ^ Colledge, p. 188

- ^ Preston, p. 30

- His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 February 1913. p. 269. Retrieved 29 March 2017.

- ^ Burt, p. 186

- ^ von Hase, pp. 35, 40, 49, 58

- ^ Burt, p. 188

- ^ Massie, p. 19

- ^ Preston, p. 32

- ^ Burt, p. 183; Goldrick, p. 156; Jellicoe, pp. 167–168, 173

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 28–30

- ^ Goldrick, pp. 200–214

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 185, 190–191, 194–196, 206, 211–212

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 217–219, 221–222

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 228, 234–235, 243, 246, 250, 253, 257–258

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c" (PDF). National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. February 1915. p. 5. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 270–271, 275, 279–280, 284, 286

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 286–290

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- ^ Corbett, frontispiece map and p. 428

- ^ Campbell, pp. 204, 208

- ^ Halpern 1995, pp. 330–332

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c" (PDF). National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. March 1917. p. 5. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ Halpern 1995, pp. 418–420

- ^ a b c Burt, p. 187

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. 1 March 1919. p. 10. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Supplement to the Monthly Navy List Showing the Organisation of the Fleet, Flag Officer's Commands, &c". National Library of Scotland. Admiralty. 1 May 1919. pp. 5, 12. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "The Navy List" (PDF). National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 December 1919. pp. 694, 707. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "The Navy List" (PDF). National Library of Scotland. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 18 October 1920. pp. 695–6, 707a, 712–13. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Burt, p. 187; Halpern 2011, pp. 304, 345, 378, 385

Bibliography

- Brooks, John (1996). "Percy Scott and the Director". In McLean, David; Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 150–170. ISBN 0-85177-685-X.

- ISBN 1-55750-315-X.

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-863-8.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8.

- ISBN 1-870423-50-X.

- ISBN 978-1-84832-225-7.

- Goldrick, James (2015). Before Jutland: The Naval War in Northern European Waters, August 1914–February 1915. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-349-9.

- ISBN 978-1-4094-2756-8.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- OCLC 13614571.

- ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.

- von Hase, Georg, Commander (1921). Kiel and Jutland. London: Skeffington and Son. )