Hadda, Afghanistan

Buddhist stupas at Hadda, by William Simpson, 1881.[1] | |

| Coordinates | 34°21′42″N 70°28′15″E / 34.361685°N 70.470752°E |

|---|---|

| Type | Group of Buddhist monasteries |

| History | |

| Founded | 1st century BCE |

| Abandoned | 9th century CE |

Haḍḍa (

Hadda is said to have been almost entirely destroyed in the fighting during the civil war in Afghanistan.

Background

Some 23,000 Greco-Buddhist sculptures, both clay and plaster, were excavated in Hadda during the 1930s and the 1970s. The findings combine elements of

Although the style of the artifacts is typical of the late Hellenistic 2nd or 1st century BCE, the Hadda sculptures are usually dated (although with some uncertainty), to the 1st century CE or later (i.e. one or two centuries afterward). This discrepancy might be explained by a preservation of late Hellenistic styles for a few centuries in this part of the world. However it is possible that the artifacts actually were produced in the late Hellenistic period.

Given the antiquity of these sculptures and a technical refinement indicative of artists fully conversant with all the aspects of Greek sculpture, it has been suggested that Greek communities were directly involved in these realizations, and that "the area might be the cradle of incipient Buddhist sculpture in

The style of many of the works at Hadda is highly Hellenistic, and can be compared to sculptures found at the Temple of Apollo in Bassae, Greece.

The

-

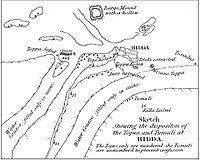

Map of Hadda by Charles Masson, 1841.

-

The village of Hadda, seen from Tapa Shotor in 1976.

Buddhist scriptures

It is believed the oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts-indeed the oldest surviving Indian manuscripts of any kind-were recovered around Hadda. Probably dating from around the 1st century CE, they were written on bark in

Tapa Shotor monastery (2nd century CE)

The earliest structures at Tapa Shotor (labelled "Tapa Shotor I" by archaeologists) date to the

A sculptural group excavated at the Hadda site of

According to Tarzi, Tapa Shotor, with clay sculptures dated to the 2nd century CE, represents the "missing link" between the Hellenistic art of Bactria, and the later stucco sculptures found at Hadda, usually dated to the 3rd-4th century CE.[8] The scultptures of Tapa Shortor are also contemporary with many of the early Buddhist sculptures found in Gandhara.[8]

-

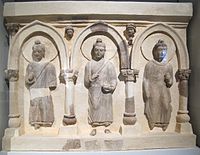

Attendants to the Buddha, Tapa Shotor (Niche V1)

-

Site of Tapa Shotor, with a protective roof.[11]

Chakhil-i-Ghoundi monastery (2nd-3rd century CE)

The Chakhil-i-Ghoundi monastery is dated to the 4th-5th century CE. It is built around the

The decoration of the stupa provides an interesting case of

-

Canopy of the stupa

-

Scene of "The Gift of Dirt", Chakhil-i-Ghoundi Stupa, Gandhara.

-

Wine and dance scene, with people in Hellenistic clothing

Tapa Kalan monastery (4th-5th century CE)

The Tapa Kalan monastery is dated to the 4th-5th century CE. It was excavated by Jules Barthoux.[12]

One of its most famous artifact is an attendant to the Buddha who display manifest Hellenistic styles, the "Genie au Fleur", today in Paris at the Guimet Museum.[13]

-

Buddha statue in Tapa Kalan, Hadda

-

Small stupa decorated with Buddhas, Tapa Kalan, 4th-5th century CE

-

Indo-Corinthian capital, with figure of the Buddha inside acanthus leaves. Tapa Kalan.

-

Buddha with flying Erotes holding a wreath overhead, Tapa Kalan, 3rd century CE

-

Heads, Tapa Kalan.[14]

-

The Great Departure

Bagh-Gai monastery (3rd-4th century CE)

The Bagh-Gai monastery is generally dated to the 3rd-4th century CE.[15] Bagh-Gai has many small stupas with decorated niches.[16]

-

Hadda number 13, Bagh Gai monastery, by Charles Masson, 1842.

-

Sculpture from Bagh-Gai

-

Decorative panel, Bagh-Gai monastery

Tapa-i Kafariha Monastery (3rd-4th century CE)

The Tapa-i Kafariha Monastery is generally dated to the 3rd-4th century CE. It was excavated in 1926–27 by an expedition led by Jules Barthoux as part of the French Archaeological Delegation to Afghanistan.

-

Hadda number 9, Tepe Kafariha, by Charles Masson, 1842.

-

Niche with the seated Boddhisatva Shakyamuni, Tapa-i Kafariha. Metropolitan Museum of Art.[17]

-

Door casing: Life of the Buddha.Musée Guimet

-

Atlas, on the base of a stupa, Tapa-i Kafariha.[18]

Tapa Tope Kalān monastery (5th century CE)

This large stupa is about 200 meters to the northeast of the modern city of Hadda. Masson called it "Tope Kalān" (Hadda 10), Barthoux "Borj-i Kafarihā", and it is now designated as "Tapa Tope Kalān".[19]

The stupa at Tope Kalan contained deposits of over 200 mainly silver coins, dating to the 4th-5th century CE. The coins included Sasanian issues of

-

Ruins of the stupa (Hadda 10)

-

Kidaritecoins from Tapa Kalan (Hadda 10)

-

Small decorative stupa at Hadda 10

Gallery

-

Polychrome Buddha, 2nd century CE, Hadda.

-

"Laughing boy" from Hadda.

-

Man with helmet, Tapa Kalan, Hadda, 3rd-4th century CE

-

Hadda Buddha fragment, 3rd-4th century CE

-

Hadda statue, 3-4th century CE

-

Head of Buddha, probably from Hadda, ca. 5th–6th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art.[21]

References

- S2CID 163368506.

- ISBN 0-691-03680-2)

- ^ Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 143.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 158.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ISBN 9788186030486.

- ^ Vanleene, Alexandra. "Tapa-e Shotor". Hadda Archeo Data Base. ArcheoDB, 2021.

- ^ See image Archived 2012-07-31 at archive.today

- ^ a b Tarzi, Zémaryalai. "Le site ruiné de Hadda": 62 ff.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ISBN 978-1-58839-224-4.

- ^ Boardman, George. The Greeks in Asia. pp. Greeks and their arts in India.

- ^ Tarzi, Zémaryalai. "Le site ruiné de Hadda".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Vanleene, Alexandra. "Tapa Tope Kalān". Hadda Archeo DB.

- ^ See image Archived 2013-01-03 at archive.today

- ^ "Photograph". RMN.

- JSTOR 43474661.

- ISBN 978-90-04-18400-8.

- ISBN 978-1-58839-224-4.

- ^ "Photograph". RMN.

- ^ Vanleene, Alexandra. "Tapa Tope Kalān". Hadda Archeo DB.

- .

- ^ "Head of Buddha, Afghanistan (probably Hadda), 5th–6th century". Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

![Head of a Buddha or Bodhisattva, facing (4th-5th century), probably Hadda, Tapa Shotor.[9][10]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Head_of_a_Buddha_or_Bodhisattva%2C_facing_%285th-6th_century%29%2C_probably_Hadda%2C_Tapa_Shotor.jpg/151px-Head_of_a_Buddha_or_Bodhisattva%2C_facing_%285th-6th_century%29%2C_probably_Hadda%2C_Tapa_Shotor.jpg)

![Site of Tapa Shotor, with a protective roof.[11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Wykopaliska_buddyjskie_-_Hadda_-_001545s.jpg/200px-Wykopaliska_buddyjskie_-_Hadda_-_001545s.jpg)

![Heads, Tapa Kalan.[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/HaddaTypes.JPG/200px-HaddaTypes.JPG)

![Niche with the seated Boddhisatva Shakyamuni, Tapa-i Kafariha. Metropolitan Museum of Art.[17]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c9/MET_DP123393.jpg/200px-MET_DP123393.jpg)

![Atlas, on the base of a stupa, Tapa-i Kafariha.[18]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/62/GandharanAtlas.JPG/200px-GandharanAtlas.JPG)

![Head of Buddha, probably from Hadda, ca. 5th–6th century. Metropolitan Museum of Art.[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/64/MET_DP264118_%28cropped%29.jpg/98px-MET_DP264118_%28cropped%29.jpg)