Halszkaraptor

| Halszkaraptor | |

|---|---|

| |

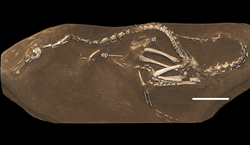

Holotype specimen

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Halszkaraptorinae |

| Genus: | †Halszkaraptor Cau et al., 2017 |

| Type species | |

| †Halszkaraptor escuilliei Cau et al., 2017

| |

Halszkaraptor (

The type specimen (

History of discovery

The

The holotype, MPC D-102/109, was found in a layer of orange sandstone of the Bayn Dzak Member of the Djadochta Formation, dating from the late Campanian, about seventy-five million years old. It consists of a relatively complete skeleton with skull. In 2017, the fossil was not further prepared. Work by the fossil dealers had at that point generally exposed the left side of the skeleton. The synchrotron revealed that the bones continued into the rock and that the piece was probably not a chimaera, an artificial assembly of bones of disparate species, though the top of the snout had been restored with plaster and some elements had been reattached to the rock by glue. The skeleton is largely articulated and not compressed. It represents a subadult individual, about one year old.[1]

The

Description

Halszkaraptor was about the size of a

Furthermore, a unique combination is present of traits that in themselves are not unique. The external bony nostril is situated behind the main body of the premaxilla, the point where it connects to the front branch of the maxilla. The descending branch of the postorbital bone is rod-shaped. The number of vertebrae of the neck and back totals twenty-two. Only the seventh, eighth and ninth neck vertebrae have pleurocoels, pneumatic depressions on their sides. The transition between the tail base and the middle tail is situated at the seventh to eighth vertebra. The third finger is longer than the second finger.[1]

Skull

The snout, though elongated, is transversely expanded in front, creating a spoon-shaped profile in top view. It is also flat, and its width is 180% of its height. The top profile in side view is hollow. The expanded area consists of a relatively long premaxilla. This bone is internally excavated by a system of air chambers. From a larger chamber in the rear, neurovascular channels permeate the entire bone, not just the sides as in

Postcranial skeleton

The

On the front neck, the neural spines, normally rectangular plates, have been reduced to a low ridge; more to behind they have disappeared. At the first five neck vertebrae, the postzygapophyses have no separating space in between them but are fused into a single lobe. With other basal maniraptoriforms these rear joint processes are sometimes connected by a plate, but in that case the bony shelf is notched by a postspinal fossa causing a concave profile in top view; in Halszkaraptor this groove is absent and the profile is convex. The neck ribs are short, no longer than the vertebral bodies. The back vertebrae are not pneumatised. The tail is not stiffened by long zygapophyses or chevrons as in derived eudromaeosaurs. The tail base is rather short in that the transition point to the middle tail, where the transverse processes cease to exist, is at the eighth vertebra. The transition is also very gradual in morphology. The neural spines of the front tail are already strongly reduced: only the first three vertebrae possess them and they are formed like low bumps.[1]

Classification

Halszkaraptor was placed in the Dromaeosauridae in 2017. A new clade Halszkaraptorinae was coined, containing Halszkaraptor and its close relatives Hulsanpes and Mahakala. The cladogram below is based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted in 2017 by Cau et al. using updated data from the Theropod Working Group. The analysis showed that Halszkaraptorinae was the basalmost known dromaeosaurid group. Halszkaraptor occupied a basal position within Halszkaraptorinae, as the sister group of a clade formed by Hulsanpes and Mahakala.[1]

Paleobiology

Andrea Cau argues that Halszkaraptor had characteristics that allowed it to spend time both in water and on land, including strong hindlimbs for running and smaller flipper-like forelimbs for swimming. The short tail would have brought the

Other researchers have either disagreed with or merely followed Cau's interpretation. In 2019, Brownstein argued that the features noted for Halszkaraptor do not directly support its ability to swim. He also suggested that this dinosaur may be a basal dromaeosaur with transitional features,[2] although Cau rebutted his claims a year later.[4] In 2021, Hone and Holtz noted that since Halszkaraptor and many modern aquatic birds with no flattened unguals is said to be semi-aquatic, having flattened unguals like Spinosaurus do not necessarily suggest that the animal can swim; they didn't propose their own view on this dinosaur's potential ability to swim.[6] In 2022, Fabbri and his colleagues argued against a semi-aquatic ecology for Halszkaraptor, noting that it had low bone density, a trait not observed in semi-aquatic animals.[3] In response, Cau has pointed out on his blog that swans similarly have low bone density yet have adaptations for semi-aquatic feeding.[7]

See also

References

- ^ S2CID 4471941. Supplementary Information

- ^ PMID 31712644.

- ^ S2CID 247630374.

- ^ PMID 32140312.

- ^ https://bmcecolevol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12862-024-02222-5

- hdl:1903/28570.

- ^ Cau, Andrea (26 March 2022). "Theropoda: L'impatto della densità ossea di Halszkaraptor sulla sua ecologia". Retrieved 28 March 2023.

External links

Media related to Halszkaraptor at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Halszkaraptor at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Halszkaraptor at Wikispecies

Data related to Halszkaraptor at Wikispecies- 3D skeletal model of Halszkaraptor escuilliei at Sketchfab