Han Chinese

漢族; 汉族 | |

|---|---|

A Han Chinese couple wearing hanfu (2013) | |

| Total population | |

| 1.4 billion[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| People's Republic of China 1,285,001,720[2] Irreligious, Chinese folk religion (including Taoism, ancestral worship, Confucianism and others), Mahayana Buddhism Minority Christianity,[33] Islam[34] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bai • Hui Other Sino-Tibetan peoples |

| Han Chinese | |

|---|---|

BUC | Háng-cŭk |

The Han Chinese or Han people[b] are an East Asian ethnic group native to Greater China. They are the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 17.5% of the global population.

The Han Chinese are the largest ethnic group in China—including

Originating from Northern China, the Han Chinese trace their ancestry to the Huaxia, a confederation of agricultural tribes that lived along the Yellow River.[41][42][43] They had their origins along the Central Plains around the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River in Northern China.[44][45][46][43] These confederation of tribes were the ancestors of the modern Han Chinese people as well as the progenitors of Chinese civilization.[47]

The term "Huaxia" was used by the ancient Chinese philosopher Confucius's contemporaries, during the Warring States era, to elucidate the shared ethnicity of all Chinese;[48] Chinese people called themselves Hua Ren.[49] Within the course of the Warring States period led to the emergence of the early discernible consciousness of the Zhou-era Chinese referring to themselves as being Huaxia (literally, "the beautiful grandeur"), which was distinctively used to adumbrate a "civilized" culture in contrast to what were perceived as "barbaric" towards the adjacent and adjoining vicinities bordering the Zhou Kingdoms that were inhabited by different non-Han Chinese peoples around them.[50][45][51][52] People of Han Chinese ancestry who possess foreign citizenship of a different country are commonly referred as Hua people (华人; 華人; Huárén) or Huazu (华族; 華族; Huázú). The two respective aforementioned terms are applied solely to those with a Han ethnic background that is semantically distinct from Zhongguo Ren (中国人; 中國人) which has connotations and implications limited to being citizens and nationals of China, especially with regards to people of non-Han Chinese ethnicity.[53][54][39]

The Huaxia tribes in Northern China continuously expanded into Southern China over the past two millennia, via military conquests and colonisation.[55][56] Huaxia culture spread southward from its northern heartland in the Yellow River Basin into the south, absorbing various non-Han ethnic groups that became sinicised over the centuries at various points in Chinese history.[57][56][45]

The name "Han people" first appeared during the era of the Northern and Southern Dynasties, and was inspired by the Han dynasty, which is considered to be one of the first golden ages in Chinese history. As a unified and cohesive empire, Han China emerged as the center of East Asian geopolitical influence at the time, projecting much of its hegemony onto its East Asian neighbours and was comparable with the contemporary Roman Empire in population size, geographical and cultural reach.[58][59][60][61] The Han dynasty's prestige and prominence influenced many of the ancient Huaxia to identify themselves as "The People of Han."[50][62][63][64][65] To this day, the Han Chinese have since taken their ethnic name from this dynasty and the Chinese script is referred to as "Han characters."[59][66][64]

Names

The name Han was derived from the name of the

The Han dynasty's founding emperor,

Prior to the Han dynasty, ancient Chinese scholars used the term Huaxia (華夏; 华夏; Huá Xià) in texts to describe China proper, while the Chinese populace were referred to as either the "various Hua" (諸華; 诸华, Zhūhuá) or the "various Xia" (诸夏; 諸夏, Zhūxià). This gave rise to a term commonly used nowadays by Overseas Chinese as an ethnic identity for the Chinese diaspora – Huaren (華人; 华人; Huá Rén, "ethnic Chinese people"), Huaqiao (华侨; 華僑; Huáqiáo, "the Chinese immigrant" meaning Overseas Chinese)[39] as well as a literary name for China – Zhonghua (中華; 中华; Zhōnghuá, "Central China").[40] Zhonghua refers more to Chinese culture, although it may also be seen as equivalent to Zhonghua minzu.[53] Some Overseas Chinese communities use Huaren or Huaqiao instead of Zhongguoren (中國人; 中国人), which has limited connotations and implications that are applied solely to those with ethnic Han ancestry while "Chinese" or Zhongguo Ren (中國人; 中国人) refers to any Chinese citizen and national regardless of their ethnic origins, due to their differing political views about the state.[54]

Among some southern Han Chinese varieties such as Cantonese, Hakka and Minnan, a different term exists – Tang Chinese (Chinese: 唐人; pinyin: Táng Rén, literally "the people of Tang"), derived from the later Tang dynasty, regarded as another golden age and high point in Chinese civilization. The term is used in everyday colloquial discourse and is also an element in one of the words for Chinatown: "street of the Tang people" (Chinese: 唐人街; pinyin: Táng Rén Jiē; Jyutping: tong4 jan4 gaai1).[72] The phrase Huá Bù, 華埠; 华埠 is also used to denote the same area.

Subgroups

Across China's vast geographical expanse, the Han Chinese can be divided into various subgroups based on their respective cultural, ethnic, genetic, linguistic, and regional features.[73][74] The historical migrations that have occurred throughout China's vast geographical expanse over the last three millennia has engendered the evolution, emergence, and encapsulation in the diverse multiplicity of assorted Han Chinese ethnic subsidiary groups found throughout the various regions of modern China today.[73][74][75][76][77]

Distribution

China

The vast majority of Han Chinese – over 1.2 billion – live in the People's Republic of China (PRC), where they constitute about 90% of its overall population.[78] Han Chinese in China have been a culturally, economically and politically dominant majority vis-à-vis the non-Han minorities throughout most of China's recorded history.[79][80] Han Chinese are almost the majority in every Chinese province, municipality and autonomous region except for the autonomous regions of Xinjiang (38% or 40% in 2010) and Tibet Autonomous Region (8% in 2014), where Uighurs and Tibetans are the majority, respectively.

Hong Kong and Macau

Han Chinese also constitute the majority in both of the special administrative regions of the PRC – about 92.2% and 88.4% of the population of Hong Kong and Macau, respectively.[81][82][failed verification] The Han Chinese in Hong Kong and Macau have been culturally, economically and politically dominant majority vis-à-vis the non-Han minorities.[83][84]

Southeast Asia

Nearly 30 to 40 million people of Han Chinese descent live in Southeast Asia.

Taiwan

There are over 22 million people of Han Chinese ancestry in living in Taiwan.[88] At first, these migrants chose to settle in locations that bore a resemblance to the areas they had left behind in mainland China, regardless of whether they arrived in the north or south of Taiwan. Hoklo immigrants from Quanzhou settled in coastal regions and those from Zhangzhou tended to gather on inland plains, while the Hakka inhabited hilly areas.

Clashes and tensions between the two groups over land, water, ethno-racial, and cultural differences led to the relocation of some communities and over time, varying degrees of intermarriage and assimilation took place. In Taiwan, Han Chinese (including both the earlier Han Taiwanese settlers and the recent mainland Chinese that arrived in Taiwan with Chiang Kai-shek in 1949) constitute over 95% of the population. They have also been a politically, culturally and economically dominant majority vis-à-vis the non-Han indigenous Taiwanese peoples.[84][83]

Others

The total overseas Chinese population worldwide number some 60 million people.[89][90][91] Overseas Han Chinese have settled in numerous countries across the globe, particularly within the Western World where nearly 4 million people of Han Chinese descent live in the United States (about 1.5% of the population),[92] over 1 million in Australia (5.6%)[14][failed verification] and about 1.5 million in Canada (5.1%),[93][94][failed verification] nearly 231,000 in New Zealand (4.9%),[20][failed verification] and as many as 750,000 in Sub-Saharan Africa.[95]

History

The Han Chinese have a rich history that spans thousands of years, with their historical roots dating back to the days of

Prehistory

The prehistory of the Han Chinese is closely intertwined with both archaeology, biology, historical textual records and mythology. The ethnic stock to which the Han Chinese originally trace their ancestry from were confederations of late

Writers during the

Although study of this period of history is complicated by the absence of contemporary records, the discovery of archaeological sites has enabled a succession of Neolithic cultures to be identified along the Yellow River. Along the central reaches of the Yellow River were the Jiahu culture (c. 7000 to 6600 BCE), the Yangshao culture (c. 5000 to 3000 BCE) and the Longshan culture (c. 3000 to 2000 BCE). Along the lower reaches of the river were the Qingliangang culture (c. 5400 to 4000 BCE), the Dawenkou culture (c. 4300 to 2500 BCE) and the Yueshi culture (c. 1900 to 1500 BCE).

Early history

Early ancient Chinese history is largely legendary, consisting of mythical tales intertwined with sporadic annals written centuries to millennia later. Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian recorded a period following the Battle of Zhuolu, during the reign of successive generations of confederate overlords (

Xia dynasty

The first dynasty to be described in Chinese historical records is the Xia dynasty (c. 2070–1600 BCE), established by Yu the Great after Emperor Shun abdicated leadership to reward Yu's work in taming the Great Flood. Yu's son, Qi, managed to not only install himself as the next ruler, but also dictated his sons as heirs by default, making the Xia dynasty the first in recorded history where genealogical succession was the norm. The civilizational prosperity of the Xia dynasty at this time is thought to have given rise to the name "Huaxia" (simplified Chinese: 华夏; traditional Chinese: 華夏; pinyin: Huá Xià, "the magnificent Xia"), a term that was used ubiquitously throughout history to define the Chinese nation.[110]

Conclusive archaeological evidence predating the 16th century BCE is, however, rarely available. Recent efforts of the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project drew the connection between the Erlitou culture and the Xia dynasty, but scholars could not reach a consensus regarding the reliability of such history.

Shang dynasty

The Xia dynasty was overthrown after the Battle of Mingtiao, around 1600 BCE, by Cheng Tang, who established the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE). The earliest archaeological examples of Chinese writing date back to this period – from characters inscribed on oracle bones used for divination – but the well-developed characters hint at a much earlier origin of writing in China.

During the Shang dynasty, people of the

Zhou dynasty

After the

Imperial history

Qin dynasty

The chaotic Warring States period of the Eastern Zhou dynasty came to an end with the unification of China by the western state of

This dynasty, sometimes phonetically spelt as the "Ch'in dynasty", has been proposed in the 17th century by Martino Martini and supported by later scholars such as Paul Pelliot and Berthold Laufer to be the etymological origin of the modern English word "China".

Han dynasty

The reign of the first imperial dynasty was to be short-lived. Due to the First Emperor's autocratic rule and his massive labor projects, which fomented rebellion among the populace, the Qin dynasty fell into chaos soon after his death. Under the corrupt rule of his son and successor

Three Kingdoms to Tang

The fall of the Han dynasty was followed by an age of fragmentation and several centuries of disunity amid warfare among rival kingdoms. During this time, areas of northern China were overrun by various non-Han nomadic peoples, which came to establish kingdoms of their own, the most successful of which was Northern Wei (established by the Xianbei). From this period, the native population of China proper was referred to as Hanren, or the "People of Han", to distinguish them from the nomads from the steppe. Warfare and invasion led to one of the first great migrations of Han populations in history, as they fled south to the Yangzi and beyond, shifting the Chinese demographic center and speeding up sinicization of the far south. At the same time most of the nomads in northern China came to be sinicized as they ruled over large Chinese populations and adopted elements of their culture and administration. Of note, the Xianbei rulers of Northern Wei ordered a policy of systematic sinicization, adopting Han surnames, institutions and culture, so the Xianbei became Han Chinese.

The Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties saw the continuation of the complete sinicization of the south coast of what is now China proper, including what are now the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong. The later part of the Tang era, as well as the Five Dynasties period that followed, saw continual warfare in north and central China; the relative stability of the south coast made it an attractive destination for refugees.

Song to Qing

The next few centuries saw successive invasions of Han and non-Han peoples from the north. In 1279, the Mongols conquered all of China, becoming the first non-Han ethnic group to do so, and established the Yuan dynasty. The Mongols divided society into four classes, with themselves occupying the top class and Han Chinese into the bottom two classes. Emigration, seen as disloyal to ancestors and ancestral land, was banned by the Song and Yuan dynasties.[114]

Zhu Yuanzhang, who had Han-centered concept of China and regarded expelling "barbarians" and restoring Han people's China as mission, established the Ming dynasty in 1368 after the Red Turban Rebellions. During this period, China referred to the Ming Empire and to the Han people living in them, and non-Han communities were separated from China.[115]

Early

Republic history

The Han nationalist revolutionary Sun Yat-sen made Han Chinese superiority a basic tenet of the Chinese revolution in the early 1900s.[119] In Sun's revolutionary philosophy, the Han identity is exclusively possessed by the so-called civilized Hua Xia people originating from the Central Plains who were former subjects of the Celestial empire and espousers of Confucianism.[118] Restoring Chinese rule to the Han majority was one of the motivations for supporters of the 1911 Revolution.[120]

Mao Zedong was critical of Han chauvinism.[117] In the latter half of the 20th century, official policy marked Han chauvinism as anti-Marxist.[119] Today, the tension between Han Chinese and ethnic minorities is compounded by China's contemporary ethnicpolicies.[118]

Culture and society

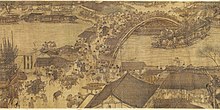

Chinese civilization is one of the world's oldest and most complex

The Han Chinese also share a distinct set of cultural practices, traditions, and beliefs that have evolved over centuries. Traditional Han customs, art, dietary habits, literature, religious beliefs, and value systems have not only deeply influenced Han culture itself, but also the cultures of its East Asian neighbors as well.

Language

Han Chinese speak various forms of the Chinese language that are descended from a common early language;[121] one of the names of the language groups is Hanyu (simplified Chinese: 汉语; traditional Chinese: 漢語), literally the "Han language". Similarly, Chinese characters, used to write the language, are called Hanzi (simplified Chinese: 汉字; traditional Chinese: 漢字) or "Han characters".

In the late imperial period, more than two-thirds of the Han Chinese population used a variant of Mandarin Chinese as their native tongue.[121] However, there was a larger variety of languages in certain areas of Southeast China, like Shanghai, Guangzhou and Guangxi.[121] Since the Qin dynasty, which standardized the various forms of writing that existed in China, a standard literary Chinese had emerged with vocabulary and grammar that was significantly different from the various forms of spoken Chinese. A simplified and elaborated version of this written standard was used in business contracts, notes for Chinese opera, ritual texts for Chinese folk religion and other daily documents for educated people.[121]

During the early 20th century, written vernacular Chinese based on Mandarin dialects, which had been developing for several centuries, was standardized and adopted to replace literary Chinese. While written vernacular forms of other varieties of Chinese exist, such as written Cantonese, written Chinese based on Mandarin is widely understood by speakers of all varieties and has taken up the dominant position among written forms, formerly occupied by literary Chinese. Thus, although residents of different regions would not necessarily understand each other's speech, they generally share a common written language, Standard Written Chinese and Literary Chinese (these two writing styles can merge into a 半白半文 writing style).

From the 1950s,

Names

Through China, the notion of hundred surnames (百家姓) is crucial identity point of the Han people.[135]

Fashion

Han Chinese clothing has been shaped through its dynastic traditions as well as foreign influences.[136] Han Chinese clothing showcases the traditional fashion sensibilities of Chinese clothing traditions and forms one of the major cultural facets of Chinese civilization.[137] Hanfu (漢服) or traditional Han clothing comprises all traditional clothing classifications of the Han Chinese with a recorded history of more than three millennia until the end of the Ming Dynasty. During the Qing dynasty, Hanfu clothing was mostly replaced by the Manchu style until the dynasty's fall in 1911, yet Han women continued to wear clothing from Ming dynasty. Manchu and Han fashions of women's clothing coexisted during the Qing dynasty.[138][139] Moreover, neither Taoist priests nor Buddhist monks were required to wear the queue by the Qing; they continued to wear their traditional hairstyles, completely shaved heads for Buddhist monks, and long hair in the traditional Chinese topknot for Taoist priests.[140][141] During the Republic of China period, fashion styles and forms of traditional Qing costumes gradually changed, influenced by fashion sensibilities from the Western World resulting modern Han Chinese wearing Western style clothing as a part of everyday dress.[142][137]

Han Chinese clothing has continued to play an influential role within the realm of traditional East Asian fashion as both the Japanese Kimono and the Korean Hanbok were influenced by Han Chinese clothing designs.[143][144][145][146][147]

Family

Han Chinese families throughout China have had certain traditionally prescribed roles, such as the family head (家長, jiāzhǎng), who represents the family to the outside world and the family manager (當家, dāngjiā), who is in charge of the revenues. Because farmland was commonly bought, sold or mortgaged, families were run like enterprises, with set rules for the allocation (分家, fēnjiā) of pooled earnings and assets.[121]

Han Chinese houses differ from place to place. In Beijing, the whole family traditionally lived together in a large rectangle-shaped house called a

Food

There is no one specific uniform cuisine of the Han Chinese since the culinary traditions and food consumed varies from Sichuan's famously spicy food to Guangdong's dim sum and fresh seafood.[149] Analyses throughout the reaches of Northern and Southern China have revealed their main staple to be rice (more likely to consumed by Southerners) as well as noodles and other wheat-based food items (which are more likely to be eaten by Northerners).[150] During China's Neolithic period, southwestern rice growers transitioned to millet from the northwest, when they could not find a suitable northwestern ecology – which was typically dry and cold – to sustain the generous yields of their staple as well as it did in other areas, such as along the eastern Chinese coast.[151]

Literature

With a rich historical literary heritage spanning over three thousand years, the Han Chinese have continued to push the boundaries that have circumscribed the standards of literary excellence by showcasing an unwaveringly exceptional caliber and extensive wealth of literary accomplishments throughout the ages. The Han Chinese possess a vast catalogue of

Drawing upon their extensive literary heritage rooted in a historical legacy spanning over three thousand years, the Han Chinese have continued to demonstrate a uniformly high level of literary achievement throughout the modern era as the reputation of contemporary Chinese literature continues to be internationally recognized.

Science and technology

The Han Chinese have made significant contributions to various fields in the advancement and progress of human civilization, including business, culture and society, governance, and science and technology, both historically and in the modern era. They have also played a crucial role in shaping the geopolitical landscape of China and the wider encompassing region of East Asia at large. The invention of paper, printing, the compass and gunpowder are celebrated in Chinese society as the Four Great Inventions.[155] Medieval Han Chinese astronomers were also among the first peoples to record observations of a cosmic supernova in 1054 AD.[156] The work of medieval Chinese polymath Shen Kuo (1031–1095) of the Song dynasty theorized that the sun and moon were spherical and wrote of planetary motions such as retrogradation as well postulating theories for the processes of geological land formation.[156]

Throughout much of history, successive

In the contemporary era, Han Chinese have continued to contribute to the development and growth of modern science and technology. Among such prominently illustrious names that have been honored, recognized, and respected for their historical groundbreaking achievements include

The 1978 Wolf Prize in Physics inaugural recipient and physicist

Other prominent Han Chinese who have made notable contributions the development and growth of modern science and technology include the medical researcher, physician, and virologist

Religion

Chinese folk religion is a set of worship traditions of the ethnic deities of the Han people. It involves the worship of various extraordinary figures in Chinese mythology and history, heroic personnel such as Guan Yu and Qu Yuan, mythological creatures such as the Chinese dragon or family, clan and national ancestors. These practices vary from region to region and do not characterize an organized religion, though many traditional Chinese holidays such as the Duanwu (or Dragon Boat) Festival, Qingming Festival, Zhongyuan Festival and the Mid-Autumn Festival come from the most popular of these traditions.

Taoism, another indigenous Han philosophy and religion, is also widely practiced by the Han in both its folk forms and as an organized religion with its traditions having been a source of vestigial perennial influence on Chinese art, poetry, philosophy, music, medicine, astronomy, Neidan and alchemy, dietary habits, Neijia and other martial arts and architecture. Taoism was the state religion during the Han and Tang eras where it also often enjoyed state patronage under subsequent emperors and successive ruling dynasties.

Confucianism, although sometimes described as a religion, is another indigenous governing philosophy and moral code with some religious elements like ancestor worship. It continues to be deeply ingrained in modern Chinese culture and was the official state philosophy in ancient China during the

During the Han dynasty,

Though Christian influence in China existed as early as the 7th century, Christianity did not gain a significant foothold in China until the establishment of contact with Europeans during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Christian beliefs often had conflicts with traditional Chinese values and customs which eventually resulted in the Chinese Rites controversy and a subsequent reduction in Christian influence in the country. Christianity grew considerably following the First Opium War, after which foreign missionaries in China enjoyed the protection of the Western powers and engaged in widespread proselytizing.[193]

Historical southward migration

Modern Southern Han Chinese – such as the Hoklo, Cantonese, and Hakka – all claim Northern Han Chinese ancestry derived from their forebearers who migrated from Northern China's Yellow River Valley between the 4th to 12th centuries. Hoklo clans living in southeastern coastal China, such as in Chaozhou and Quanzhou–Zhangzhou, originated from northern China's Henan province during the Tang dynasty.[194]

There were several periods of mass migration of Han people to Southeastern and Southern China throughout history.[75] The ancestors of the Cantonese are said to be Northern Han Chinese who moved to Guangdong, while the Yue descendants were the indigenous minorities who practised tattooing, as described in "The Real Yue People" (真越人; zhēn yuèrén) essay by Qu Dajun, a Cantonese scholar who extolled his people's Chineseness.[195]

Northern Vietnam, Guangdong and Yunnan all experienced a major surge in Han Chinese migrants during

The Han Chinese "Eight Great Surnames" were eight noble families who migrated from Northern China to Fujian in Southern China due to the uprising of the five barbarians when the Eastern Jin was founded, the Hu, He, Qiu, Dan, Zheng, Huang, Chen and Lin surnames.[200][201][202][203]

The

Different waves of migration of Han Chinese belonging to the aristocracy from Northern China to the south at different times – with some arriving in the 300s–400s and others in the 800s–900s – resulted in the formation of distinct lineages.

The

The first Ming dynasty emperor

Genetics

The Han Chinese show a close genetic relationship with other modern East Asian populations such as the Koreans and Yamato.[222][223][224][225][226][227][228] A 2018 research paper found that while the Han Chinese are closely related to the Koreans and Yamato in terms of a correlative genetic relationship, they are also easily genetically distinguishable from them. And that the same Han Chinese subgroups are genetically closer to each other relative to their Korean and Yamato counterparts, but are still easily distinguishable from each other.[228] Research published in 2020 found the Yamato Japanese population to be overlapped with that of the northern Han Chinese.[229]

The genetic makeup of the modern Han Chinese is not purely uniform in terms of physical appearance and biological structure due to the vast geographical expanse of China and the migratory percolations that have occurred throughout it over the last three millennia. This has also engendered the emergence and evolution of the diverse multiplicity of assorted Han subgroups found throughout the various regions of modern China today. Comparisons between the Y chromosome single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of modern Northern Han Chinese and 3000 year old Hengbei ancient samples from China's Central Plains show that they are extremely similar to each other, which confirms the genetic continuity bequeathed by the ancient Chinese of Hengbei and the present-day Northern Han Chinese inheritors that currently inhabit it in the contemporary era. These findings demonstrate that the core fundamental structural basis that shaped the genetic makeup of the present-day Northern Han Chinese was already formed three thousand years ago.[231] The reference population for the Chinese used in Geno 2.0 Next Generation is 81% Eastern Asia, 2% Finland and Northern Siberia, 8% Central Asia, and 7% Southeast Asia & Oceania.[232]

Y-chromosome

However, the mtDNA of Han Chinese increases in diversity as one looks from northern to southern China, which suggests that the influx of male Han Chinese migrants intermarried with the local female non-Han aborigines after arriving in what is now modern-day Guangdong, Fujian, and other regions of southern China.[246][247] Despite this, tests comparing the genetic profiles of northern Han, southern Han, and non-Han southern natives determined that haplogroups O1b-M110, O2a1-M88 and O3d-M7, which are prevalent in non-Han southern natives, were only observed in some southern Han Chinese (4% on average), but not in the northern Han genetic profile. Therefore, this proves that the male contribution of the southern non-Han natives in the southern Han genetic profile is limited, assuming that the frequency distribution of Y lineages in southern non-Han natives represents that prior to the expansion of Han culture which originated two thousand years ago from the north.[246][76]

In contrast, there is evidence that consistently shows the strong genetic similarities in the Y chromosome haplogroup distribution between the modern southern and northern Han Chinese population, and the result of principal core component analysis indicates that almost all modern Han Chinese populations form a tight cluster in their Y chromosome. However, other biological research findings have also demonstrated that the paternal lineages Y-DNA O-M119,[248] O-P201,[249] O-P203[249] and O-M95[250] are found in both Southern Han Chinese and Southern non-Han minorities, but more commonly in the latter. In fact, these paternal markers are in turn less frequent in northern Han Chinese.[251] Another study puts the Han Chinese into two groups: Northern and southern Han Chinese, and it demonstrates that the core genetic characteristics of the present-day northern Han Chinese was already formed more than three-thousand years ago in the Central Plain area.[252]

The estimated contribution of northern Han to the southern Han is substantial in the paternal ancestral lineages in addition to a geographic cline that exists for its corresponding maternal ancestry. As a result, the northern Han Chinese are the primary benefactors that contributed to the paternal gene pool of the modern southern Han Chinese as a result of the successive migratory waves that have occurred from the north to what is now modern Southern China. However, it is noteworthy that the southward expansion process that occurred two thousand years ago was largely dominated by males, as is shown by a greater contribution to the Y-chromosome than the mtDNA from northern to southern Han. These genetic findings and observations are in concurrence with historical records confirming the continuous and large migratory waves of northern Han Chinese inhabitants escaping dynastic changes, geopolitical upheavals, instability, warfare and famine into what is now today modern Southern China.[253][254][255][207][208][256][257][211][212][213][214][215][216][217][218][219]

Successive waves of Han migration and subsequent intermarriage and cross-cultural dialogue between the northern Han migrants and the non-Han aborigines gave rise to modern Chinese demographics with a dominant Han Chinese super-majority and minority non-Han Chinese indigenous peoples in the south over the past two thousand years.[254] Aside from these large migratory waves, other smaller southward migrations occurred during almost all periods over the past two millennia.[246] A study by the Chinese Academy of Sciences into the gene frequency data of Han sub-populations and ethnic minorities in China, showed that Han sub-populations in different regions are also genetically quite close to the local ethnic non-Han minorities, meaning that in many cases, the blood of ethnic minorities had mixed into Han genetic substrate through varying degrees of intermarriage, while at the same time, the blood of the Han had also mixed into the genetic substrates of the local ethnic non-Han minorities.[258]

A recent, and to date the most extensive, genome-wide association study of the Han population, shows that geographic-genetic stratification from north to south has occurred and centrally placed populations act as the conduit for outlying ones.[259] Ultimately, with the exception in some ethnolinguistic branches of the Han Chinese, such as Pinghua and Tanka people,[260] there is a "coherent genetic structure" found in the entirety of the modern Han Chinese populace.[261]

Typical Y-DNA haplogroups of present-day Han Chinese include Haplogroup O-M122, C, Haplogroup N and Haplogroup Q-M120, and these haplogroups also have been found (alongside some members of Haplogroup N-M231, Haplogroup O-M95, and unresolved Haplogroup O-M175) among a selection of ancient human remains recovered from the Hengbei archeological site in Jiang County, Shanxi Province, China, an area that was part of the suburbs of the capital (near modern Luoyang) during the Zhou dynasty.[262]

Notes

- ^ Of the 710,000 Chinese nationals living in Korea in 2016, 500,000 are ethnic Koreans.

- ^ simplified Chinese: 汉族; traditional Chinese: 漢族; pinyin: Hànzú; lit. 'Han ethnic group' or

simplified Chinese: 汉人; traditional Chinese: 漢人; pinyin: Hànrén; lit. 'Han people'

References

- ISBN 978-1-61069-018-8. Archivedfrom the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- ^ a b CIA Factbook Archived 13 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine: "Han Chinese 91.1%" out of a reported population of 1,410,539,758 (2022 est.)

- ^ "Taiwan snapshot". Archived from the original on 15 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Population structure of Han Chinese in the modern Taiwanese population based on 10,000 participants in the Taiwan Biobank project | Human Molecular Genetics | Oxford Academic". Academic.oup.com. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Overseas Compatriot Affairs Commission, R.O.C." Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "confirmed latest statistics". 2022. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Race Reporting for the Asian Population by Selected Categories: 2010 more information". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "Selected Population Profile in the United States". census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Jumlah dan Persentase Penduduk menurut Kelompok Suku Bangsa" (PDF). media.neliti.com (in Indonesian). Kewarganegaraan, suku bangsa, agama dan bahasa sehari-hari penduduk Indonesia. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Topic: Demographics of Singapore". Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "The World Factbook". Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. "Population by Ethnic Origin by Province". Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Macrohon, Pilar (21 January 2013). "Senate declares Chinese New Year as special working holiday" (Press release). PRIB, Office of the Senate Secretary, Senate of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Australia". 2016 Census QuickStats. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- S2CID 157718431. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "在日华人统计人口达92万创历史新高". www.rbzwdb.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "2011 Census: Ethnic group, local authorities in the United Kingdom". Office for National Statistics. 11 October 2013. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "South America: Peru". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Cittadini Non Comunitari: Presenza, Nuovi Ingressi e Acquisizioni di Cittadinanza: Anni 2015–2016" (PDF). Istat.it. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b "2018 Census totals by topic – national highlights | Stats NZ". Stats.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "BiB – Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung – Pressemitteilungen – Zuwanderung aus außereuropäischen Ländern fast verdoppelt". Bib-demografiie.de (in German). Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Foreign national population in Korea up more than 40% in 5 yrs". Maeil Business News Korea. 8 September 2016. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ "Chinese living in Kingdom more than doubles since '17". 14 September 2018. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ "Argentina-China Relations Archives". Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Chinese Argentines and the Pace of Cultural Integration". 26 July 2011. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Cifras de Población a 1 de enero de 2016 : Estadística de Migraciones 2015 : Adquisiciones de Nacionalidad Española de Residentes 2015" (PDF). Ine.es (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Chinese-Mexicans celebrate repatriation to Mexico". The San Diego Union-Tribune. 23 November 2012. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ "Population by Religion, Sex and Census Year". Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ "Национальный состав населения по субъектам Российской Федерации". Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- .

- ^ "X Censo Nacional de Población y VI de Vivienda 2011, Características Sociales y Demográficas" (PDF). National Institute of Statistics and Census of Costa Rica. July 2012. p. 61. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

Cuadro 23. Costa Rica: Población total por autoidentificación étnica-racial, según provincia, zona y sexo. Chino(a) 9,170

- ^ "Migration and Diversity - CSO - Central Statistics Office". CSO. 30 May 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ISSN 2192-9289

- ^ Measuring Religion in China. 30 August 2023. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ 中華民國國情簡介 [ROC Vital Information]. Executive Yuan (in Chinese (Taiwan)). 2016. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

臺灣住民以漢人為最大族群,約占總人口97%

- ISBN 978-986-04-2302-0. Archived(PDF) from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- ^ "Home" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-9971-69-599-6. Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-306-47754-6.

The name "Han" was derived from the Han River, an upper tributary of the Yangtze River. It was further strengthened by the famous Han Empire (206 BC–220 AD) which lasted for several hundred years when the people began active interactions with the outside world.

- S2CID 156043981.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61069-017-1.

- ^ a b Schliesinger, Joachim (2016). Origin of Man in Southeast Asia 2: Early Dominant Peoples of the Mainland Region. Booksmango. pp. 13–14.

- ISBN 978-1-138-91825-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-674-08846-7.

- ISBN 978-1-59158-294-6.

- OCLC 50755038.

- ISBN 978-1-316-35228-1. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ISBN 978-81-7304-425-0. Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8160-2693-7.

- ^ Schliesinger, Joachim (2016). Origin of Man in Southeast Asia 2: Early Dominant Peoples of the Mainland Region. Booksmango. p. 14.

- ISBN 978-1-10754489-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-135-04635-4. Archivedfrom the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-981-230-110-9. Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ a b Schliesinger, Joachim (2016). Origin of Man in Southeast Asia 2: Early Dominant Peoples of the Mainland Region. Booksmango. pp. 10–17.

- ^ a b Dingming, Wu (2014). A Panoramic View of Chinese Culture. Simon & Schuster.

- ISBN 978-1-61069-017-1.

- ^ Cohen, Warren I. (2000). East Asia At The Center: Four Thousand Years of Engagement With The World. Columbia University Press. p. 59.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61069-017-1.

- ^ Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 119.

- ISBN 978-0-231-15319-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-60384-204-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4408-2864-5.

- ^ a b Eno, R. The Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – A.D. 220) (PDF). Indiana University Press. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ISBN 978-81-8274-611-4.

- ^ a b Schaefer (2008), p. 279.

- ISBN 978-1-4522-6586-5. Archivedfrom the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

Although the term han has its roots in the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), which began around the Yellow River and then spread out, the concept really became nationalized early in this century.

- ^ Hsu, Cho-yun; Lagerwey, John (2012). Y.S. Cheng, Joseph (ed.). China: A Religious State. Columbia University Press. p. 126.

- ^ "Definition of Han by Oxford". Oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- ^ "Definition of Han by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- .

- ^ PMID 17317646.

- ^ PMID 25938511.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- ^ S2CID 4301581.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-135-40500-7. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ CIA Factbook Archived 13 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine: "Han Chinese 91.6%" out of a reported population of 1,384,688,986 billion (July 2018 est.)

- ISBN 978-0-385-72186-8.

- ^ Chua, Amy L. (2000). "The Paradox of Free Market Democracy: Rethinking Development Policy". Harvard International Law Journal. 41: 325. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- Census and Statistics Department. February 2016. p. 37. Archivedfrom the original on 20 November 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- Statistics and Census Service. May 2017. Archivedfrom the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ a b c Chua, Amy L. (2000). "The Paradox of Free Market Democracy: Rethinking Development Policy". Harvard International Law Journal. 41: 328. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-385-72186-8.

- .

- ^ a b Yim, Onn Siong (2005). Y chromosome diversity in Singaporean Han Chinese population subgroups (Master). National University of Singapore. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ Vatikiotis, Michael (12 February 1998). Entrerepeeneurs (PDF). Bangkok: Far Eastern Economic Review. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Taiwan Population (2017) – World Population Review". worldpopulationreview.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ "Chinese education companies scramble to teach Overseas Children to learn Chinese language". GETChina Insights. 2021 [December 2, 2021]. Archived from the original on 15 February 2024. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Zhuang, Guotu (2021). "The Overseas Chinese: A Long History". UNESDOC. p. 24. Archived from the original on 15 February 2024. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- Project MUSE 658015.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables". statcan.gc.ca. 25 October 2017. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada". statcan.gc.ca. 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ China and Africa: Stronger Economic Ties Mean More Migration Archived 29 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine, By Malia Politzer, Migration Information Source, August 2008.

- ^ Roberts, John A.G (2001). A History of China. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 5.

- ^ a b Jacques, Martin (26 October 2012). "A Point Of View: How China sees a multicultural world". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-61069-017-1.

- ISBN 978-90-272-2444-6.

- ISBN 978-3-662-51507-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-32305-3.

- S2CID 156043981.

- ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ "Common traits bind Jews and Chinese". Asia Times. 10 January 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ISBN 978-0-7591-0458-7.

- ^ Stuart-Fox, Martin (2003). A Short History of China and Southeast Asia: Tribute, Trade and Influence. Allen & Unwin (published 1 November 2003). p. 21.

- ISBN 978-0-7656-1823-8.

- PMID 18270655.

- ISBN 978-0-7914-0460-7, archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2021, retrieved 5 October 2020

- ISBN 978-0-470-82604-1.

- ^ a b Theobald, Ulrich. "The Feudal State of Wu 吳 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". Chinaknowledge.de. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "China The Zhou Period". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Clayton D. Brown Research on Chinese History: Ethnology, Archaeology, and Han Identity". Claytonbrown.org. Archived from the original on 18 January 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-7546-1793-8. Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ a b Yonglin Jiang (2018). "Thinking About the 'Ming China' Anew: The Ethnocultural Space In A Diverse Empire-With Special Reference to the 'Miao Territory'" (pdf). Bryn Mawr College. Archived from the original on 7 February 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- S2CID 162684575.

- ^ a b Ian Buruma (February 2022). "The Great Wall of Steel". Harper's Magazine. Archived from the original on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Weiying Wu (2023). "Han-Nationalism Throughout the Ages" (pdf). Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on 15 February 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b "Han Chauvinism/Exceptionalism: The Problem with it". The SAIS Observer. 7 April 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Revolution of 1911". China Daily. 27 July 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cohen, Myron L. "Late Imperial China and Its Legacies". Kinship, Contract, Community, And State: Anthropological Perspectives on China. pp. 41–45, 50.

- ISBN 978-1846143106.

- ISBN 978-1594205460.

- ^ Walker, Hugh Dyson (2012). East Asia: A New History. AuthorHouse. p. 2.

- ISBN 978-0674064010.

- JSTOR 20038053.

- ISBN 978-9812295941.

- ISBN 978-1567205251.

- ISBN 978-1594205460.

- ISBN 978-0231153195.

- ISBN 978-0415670029.

- ISBN 9783319718859. Archivedfrom the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- PMID 35369161.

- ISBN 9781610690188. Archivedfrom the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Surnames and Han Chinese Identity Archived 22 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine, University of Washington

- ISBN 978-1-59265-019-4.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4196-4893-9.

- ISBN 978-7-104-00359-5.

- ISBN 978-1-59265-019-4. Archivedfrom the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

Men's clothing in the Qing Dyansty consisted for the most part of long silk gowns and the so-called "Mandarin" jacket, which perhaps achieved their greatest popularity during the latter Kangxi Period to the Yongzheng Period. For women's clothing, Manchu and Han systems of clothing coexisted.

- ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9. Archivedfrom the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Gerolamo Emilio Gerini (1895). "Chŭlăkantamangala: Or, The Tonsure Ceremony as Performed in Siam". The Bangkok Times. pp. 11–. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- ^ Mei Hua, Chinese Clothing, Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 133–34

- ISBN 978-0-525-24574-2, archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020, retrieved 21 May 2020

- ISBN 978-0-87654-598-0.

- ISBN 978-0-295-98155-0.

- ISBN 978-0-7591-2150-8. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ Montgomery County Public Schools Foreign Language Department (August 2006). Si-he-yuan. Montgomery County Public Schools. pp. 1–8. Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ "十大经典川菜 你吃过哪些?". 阿波罗新闻网 (in Chinese (China)). 18 November 2014. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- JSTOR 2642652.

- ^ Sagart, Laurent (January 2008). "The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia: A linguistic and archaeological model". Past Human Migrations in East Asia: Matching: 137. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ Julia Lovell (5 February 2016). "'The Big Red Book of Modern Chinese Literature,' Edited by Yunte Huang". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Kevin (23 August 2015). "2015 Hugo Award Winners Announced". The Hugo Awards. Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ "HCAA 2016 Winners". Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ISBN 978-1138826700.

- ^ ISBN 978-1291208917.

- ^ Ferguson, Ben (7 October 2009). "'Master of Light' awarded Nobel Prize". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Qian Xuesen". The Daily Telegraph. 22 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Chien-Shiung Wu". National Women's Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 22 May 2014. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ O'Connor, J J; Robertson, E F. "Chern biography: Shiing-shen Chern". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Sanders, Robert (6 December 2004). "Renowned mathematician Shiing-Shen Chern, who revitalized the study of geometry, has died at 93 in Tianjin, China". Berkeley News. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Interview with Shiing Shen Chern" (PDF). Notices of the MS. 45 (7). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 January 2024.

- S2CID 122548419.

- ^ "Taking the Long View: The Life of Shiing-shen Chern". zalafilms.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "The Wolf Prize in Agriculture". Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Obituary Yuan Longping". The Economist. Vol. 439 Number 9247. 29 May 2021. p. 86. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Bradsher, Keith; Buckley, Chris (23 May 2021). "Yuan Longping, Plant Scientist Who Helped Curb Famine, Dies at 90". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ^ "Dr. Monty Jones and Yuan Longping". World Food Prize. 2004. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ "CCTV-"杂交水稻之父"袁隆平" ["Father of hybrid rice" Yuan Longping]. China Central Television. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- .

- PMID 21079590.

- PMID 22608086.

- PMID 21151123.

- ^ "Dr David Ho, Man of the Year". Time. 30 December 1996. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ Knapp, Alex (27 August 2020). "The Inside Story Of Biotech's Barnum And His Covid Cures". Forbes. Archived from the original on 25 November 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ^ a b Light, Leti McNeill (2015). "Visions of Progress and Courage [Dr. Patrick Soon-Shiong — Medical Visionary Award]" (print and online). U Magazine (Spring): 42f. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- S2CID 25795725.

The first attempt to cure type 1 diabetes by pancreas transplantation was done at the University of Minnesota, in Minneapolis, on December 17, 1966… [This] opened the door to a period, between the mid-[1970s] to mid-[1980s] where only segmental pancreatic grafts were used... In the late [1970s] – early [1980s], three major events… boosted the development of pancreas transplantation… [At] the Spitzingsee meetings, participants had the idea to renew the urinary drainage technique of the exocrine secretion of the pancreatic graft with segmental graft and eventually with whole pancreaticoduodenal transplant. That was clinically achieved during the mid-[1980s] and remained the mainstay technique during the next decade. In parallel, the Swedish group developed the whole pancreas transplantation technique with enteric diversion. It was the onset of the whole pancreas reign. The enthusiasm for the technique was rather moderated in its early phase due to the rapid development of liver transplantation and the need for sharing vascular structures between both organs, liver and pancreas. During the modern era of immunosuppression, the whole pancreas transplantation technique with enteric diversion became the gold standard… [for SPK, PAK, PTA].

- ^ Thomas Chang, Professor of Physiology | About McGill – McGill University Archived 27 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Mcgill.ca. Retrieved on 2012-05-25.

- ^ The Governor General of Canada > Honours > Recipients > Thomas Ming Swi Chang Archived 6 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine. Gg.ca. Retrieved on 2020-03-03.

- ^ "Min Chueh Chang". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ "Chang Min-Chueh". Britannica Online for Kids. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Maugh II, Thomas (2 December 1987). "Discovered Human Growth Hormone: Choh Hao Li, 74; Endocrinologist at UC". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ "Choh Hao Li". National Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Wright, Pearce (11 December 2001). "Joe Hin Tjio The man who cracked the chromosome count". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (7 December 2001). "Joe Hin Tjio, 82; Research Biologist Counted Chromosomes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "News from the National Academies". National Academy of Sciences. 4 January 2007. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ "Dr. Yuan-Cheng 'Bert' Fung". National Academy of Engineering. 2007. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ "Consensus during the Cold War: back to Alma-Ata". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86 (10): 737–816. October 2008. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012.

- ^ "China's village doctors take great strides". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 86 (12): 909–88. December 2008. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008.

- ^ Anderlini, Jamil (7 November 2014). "The rise of Christianity in China". www.ft.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- S2CID 148800029.

- ISBN 978-0-8028-2975-7.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-2857-7. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-4128-3248-9. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Nicolas Olivier Tackett. "The Transformation of Medieval Chinese Elites (850–1000 C.E.)" (PDF). History.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ISBN 978-90-04-17585-3. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-7607-1973-2. Archivedfrom the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7607-1976-3. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ISBN 978-9047429463. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ISBN 978-3643903297. Archivedfrom the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ISBN 0804742618. Archivedfrom the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ISBN 0824823338. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ISBN 978-962-996-227-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ISBN 978-962-996-227-2. Archivedfrom the original on 29 December 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-674-00249-4. Archivedfrom the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-9811016370. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ a b "Six Dynasties". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 4 December 2008. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Entenmann, Robert Eric (1982). Migration and settlement in Sichuan, 1644-1796. Harvard University. p. 14. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ISBN 978-9004355248. Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0231528184. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1615301096. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ a b Chinese journal of international law, Volume 3. 2004. p. 631. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1588438119. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1442277892. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ ISBN 978-1461633112. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ ISBN 113942551X. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ a b Herklots, Geoffrey Alton Craig (1932). The Hong Kong Naturalist, Volumes 3-4. Newspaper Enterprise Limited. p. 120. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ ISBN 0759104581. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ISBN 080475148X. Archivedfrom the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ISBN 068413943X. Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- PMID 8751859.

- PMID 25029633.

- PMID 33292737.

- from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- PMID 28164156.

- PMID 29636655.

- ^ PMID 29636655.

- PMID 32355288.

- S2CID 28730957.

- PMID 25938511.

- ^ Reference Populations - Geno 2.0 Next Generation . (2017). The Genographic Project. Retrieved 15 May 2017, from link. Archived 7 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- PMID 21505448.

- ^ Rui-Jing Gan, Shang-Ling Pan, Laura F. Mustavich, Zhen-Dong Qin, Xiao-Yun Cai, Ji Qian, Cheng-Wu Liu, Jun-Hua Peng, Shi-Lin Li, Jie-Shun Xu, Li Jin, Hui Li, and The Genographic Consortium, "Pinghua population as an exception of Han Chinese’s coherent genetic structure." J Hum Genet (2008) 53:303–313. DOI 10.1007/s10038-008-0250-x

- ^ PMID 11481588.

- ^ S2CID 6559289.

- ^ PMID 16489223.

- PMID 35462161.

- ^ PMID 24965575.

- S2CID 221359145.

- PMID 32635262.

- from the original on 2 March 2024. Retrieved 2 March 2024.

- PMID 15793703.

- ^ PMID 36973821.

- ^ PMID 19088127.

- ^ S2CID 4301581. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 March 2009.

- PMID 18212820.

- PMID 18482451.

- ^ PMID 20207712.

- PMID 6114819.

- PMID 21505448.

- PMID 25938511.

- ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- ^ S2CID 4301581.

- ^ Crawford, Dorothy H.; Rickinson, Alan; Johannessen, Ingolfur (2014). Cancer Virus: The story of Epstein-Barr Virus. Oxford University Press (published 14 March 2014). p. 98.

- ^ Entenmann, Robert Eric (1982). Migration and settlement in Sichuan, 1644-1796. Harvard University. p. 14. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ISBN 978-9004355248. Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- S2CID 1924085.

- PMID 19944401.

- PMID 5092429.

- PMID 18270655.

- PMID 25938511.

Further reading

- Yuan, Haiwang (2006). The Magic Lotus Lantern and Other Tales from the Han Chinese. Westport, Conn.: Libraries Unlimited. OCLC 65820295.

- ISBN 978-0984590988.

- Joniak-Lüthi, Agnieszka (2015). The Han: China's Diverse Majority. Washington, DC: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295741789(paperback: 2017).

External links

![]() Media related to Han Chinese people at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Han Chinese people at Wikimedia Commons