Han dynasty

Han | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

A map of the Western Han dynasty in 2 AD[1]

| |||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||

• 202–195 BC (first) | Emperor Gaozu | ||||||||||||||

• 141–87 BC | Emperor Wu | ||||||||||||||

• 74–48 BC | Emperor Xuan | ||||||||||||||

• 25–57 AD | Emperor Guangwu | ||||||||||||||

• 189–220 AD (last) | Emperor Xian | ||||||||||||||

Cao Can | |||||||||||||||

• 189–192 AD | Dong Zhuo | ||||||||||||||

• 208–220 AD | Cao Cao | ||||||||||||||

• 220 AD | Cao Pi | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Imperial | ||||||||||||||

| 206 BC | |||||||||||||||

• Battle of Gaixia; Liu Bang proclaimed emperor | 202 BC | ||||||||||||||

| 9–23 AD | |||||||||||||||

• Abdication to Cao Wei | 220 AD | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 50 BC est. (Western Han peak)[2] | 6,000,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| 100 AD est. (Eastern Han peak)[2] | 6,500,000 km2 (2,500,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 2 AD[3] | 57,671,400 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Ban Liang coins and Wu Zhu coins | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||

| Han dynasty | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hanyu Pinyin | Hàn | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

The Han dynasty (

The Han dynasty saw an

The Han dynasty had many conflicts with the

Etymology

According to the

History

Western Han

China's first

At the beginning of the Western Han (

By 196, the Han court had replaced all of these kings with royal Liu family members, with the lone exception of Changsha. The loyalty of non-relatives to the emperor was questioned,[14] and after several insurrections by Han kings—with the largest being the Rebellion of the Seven States in 154—the imperial court began enacting a series of reforms that limited the power of these kingdoms in 145, dividing their former territories into new commanderies under central control.[15] Kings were no longer able to appoint their own staff; this duty was assumed by the imperial court.[16][17] Kings became nominal heads of their fiefs and collected a portion of tax revenues as their personal incomes.[16][17] The kingdoms were never entirely abolished and existed throughout the remainder of Western and Eastern Han.[18]

To the north of

In retaliation, the Xiongnu invaded what is now Shanxi, where they defeated the Han forces at Baideng in 200 BC.[22][23] After negotiations, the heqin agreement in 198 BC nominally held the leaders of the Xiongnu and the Han as equal partners in a royal marriage alliance, but the Han were forced to send large amounts of tribute items such as silk clothes, food, and wine to the Xiongnu.[24][25][26]

Despite the tribute and negotiation between

However, a court conference the following year convinced the majority that a limited engagement at Mayi involving the assassination of the Chanyu would throw the Xiongnu realm into chaos and benefit the Han.[33][34] When this plot failed in 133 BC,[35] Emperor Wu launched a series of massive military invasions into Xiongnu territory. The assault culminated in 119 BC at the Battle of Mobei, when Han commanders Huo Qubing (d. 117 BC) and Wei Qing (d. 106 BC) forced the Xiongnu court to flee north of the Gobi Desert, and Han forces reached as far north as Lake Baikal.[36][37]

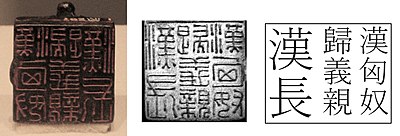

After Wu's reign, Han forces continued to fight the Xiongnu. The Xiongnu leader

In 121 BC, Han forces expelled the Xiongnu from a vast territory spanning the Hexi Corridor to Lop Nur. They repelled a joint Xiongnu-Qiang invasion of this northwestern territory in 111 BC. In that same year, the Han court established four new frontier commanderies in this region to consolidate their control: Jiuquan, Zhangyi, Dunhuang, and Wuwei.[40][41][42] The majority of people on the frontier were soldiers.[43] On occasion, the court forcibly moved peasant farmers to new frontier settlements, along with government-owned slaves and convicts who performed hard labour.[44] The court also encouraged commoners, such as farmers, merchants, landowners, and hired labourers, to voluntarily migrate to the frontier.[45]

Even before the Han's expansion into Central Asia, diplomat

From c. 115 BC until c. 60 BC, Han forces fought the Xiongnu over control of the oasis city-states in the Tarim Basin. The Han was eventually victorious and established the

To pay for his military campaigns and colonial expansion, Emperor Wu

The government monopolies were eventually repealed when a political faction known as the Reformists gained greater influence in the court. The Reformists opposed the Modernist faction that had dominated court politics in Emperor Wu's reign and during the subsequent

Wang Mang's reign and civil war

Wang Zhengjun (71 BC – 13 AD) was first empress, then empress dowager, and finally grand empress dowager during the reigns of the Emperors Yuan (r. 49–33 BC), Cheng (r. 33–7 BC), and Ai (r. 7–1 BC), respectively. During this time, a succession of her male relatives held the title of regent.[68][69] Following the death of Ai, Wang Zhengjun's nephew Wang Mang (45 BC – 23 AD) was appointed regent as Marshall of State on 16 August under Emperor Ping (r. 1 BC – 6 AD).[70]

When Ping died on 3 February 6 AD, Ruzi Ying (d. 25 AD) was chosen as the heir and Wang Mang was appointed to serve as acting emperor for the child.[70] Wang promised to relinquish his control to Liu Ying once he came of age.[70] Despite this promise, and against protest and revolts from the nobility, Wang Mang claimed on 10 January that the divine Mandate of Heaven called for the end of the Han dynasty and the beginning of his own: the Xin dynasty (9–23 AD).[71][72][73]

Wang Mang initiated a series of major reforms that were ultimately unsuccessful. These reforms included outlawing slavery, nationalizing land to equally distribute between households, and introducing new currencies, a change which debased the value of coinage.[74][75][76][77] Although these reforms provoked considerable opposition, Wang's regime met its ultimate downfall with the massive floods of c. 3 AD and 11 AD. Gradual silt buildup in the Yellow River had raised its water level and overwhelmed the flood control works. The Yellow River split into two new branches: one emptying to the north and the other to the south of the Shandong Peninsula, though Han engineers managed to dam the southern branch by 70 AD.[78][79][80]

The flood dislodged thousands of peasant farmers, many of whom joined roving bandit and rebel groups such as the

The Gengshi Emperor (r. 23–25 AD), a descendant of Emperor Jing (r. 157–141 BC), attempted to restore the Han dynasty and occupied Chang'an as his capital. However, he was overwhelmed by the Red Eyebrow rebels who deposed, assassinated, and replaced him with the puppet monarch Liu Penzi.[83][84] Gengshi's distant cousin Liu Xiu, known posthumously as Emperor Guangwu (r. 25–57 AD), after distinguishing himself at the Battle of Kunyang in 23 AD, was urged to succeed Gengshi as emperor.[85][86]

Under Guangwu's rule the Han Empire was restored. Guangwu made Luoyang his capital in 25 AD, and by 27 AD his officers Deng Yu and Feng Yi had forced the Red Eyebrows to surrender and executed their leaders for treason.[86][87] From 26 until 36 AD, Emperor Guangwu had to wage war against other regional warlords who claimed the title of emperor; when these warlords were defeated, China reunified under the Han.[88][89]

The period between the foundation of the Han dynasty and Wang Mang's reign is known as the Western Han (traditional Chinese: 西漢; simplified Chinese: 西汉; pinyin: Xīhàn) or Former Han (traditional Chinese: 前漢; simplified Chinese: 前汉; pinyin: Qiánhàn) (206 BC – 9 AD). During this period the capital was at Chang'an (modern Xi'an). From the reign of Guangwu the capital was moved eastward to Luoyang. The era from his reign until the fall of Han is known as the Eastern Han or Later Han (25–220 AD).[90]

Eastern Han

The Eastern Han (traditional Chinese: 東漢; simplified Chinese: 东汉; pinyin: Dōnghàn), also known as the Later Han (後漢; 后汉; Hòuhàn), formally began on 5 August AD 25, when Liu Xiu became Emperor Guangwu of Han.[91] During the widespread rebellion against Wang Mang, the state of Goguryeo was free to raid Han's Korean commanderies; Han did not reaffirm its control over the region until AD 30.[92]

The

During the turbulent reign of Wang Mang, China lost control over the Tarim Basin, which was conquered by the Northern Xiongnu in AD 63 and used as a base to invade the Hexi Corridor in

At the

Ban Chao (d. AD 102) enlisted the aid of the Kushan Empire, which controlled territory across South and Central Asia, to subdue Kashgar and its ally Sogdiana.[105][106] When a request by Kushan ruler Vima Kadphises (r. c. 90 – c. 100 AD) for a marriage alliance with the Han was rejected in AD 90, he sent his forces to Wakhan (modern-day Afghanistan) to attack Ban Chao. The conflict ended with the Kushans withdrawing because of lack of supplies.[105][106] In AD 91, the office of Protector General of the Western Regions was reinstated when it was bestowed on Ban Chao.[107]

Foreign travellers to the Eastern Han empire included

A

When Empress Dowager Deng died,

Students from the

Following Huan's death, Dou Wu and the Grand Tutor

Under

End of the Han dynasty

The Partisan Prohibitions were repealed during the

Zhang Lu's rebellion, in what is now northern Sichuan and southern Shaanxi, was not quelled until 215 AD.[146] Zhang Jue's massive rebellion across eight provinces was annihilated by Han forces within a year; however, the following decades saw much smaller recurrent uprisings.[147] Although the Yellow Turbans were defeated, many generals appointed during the crisis never disbanded their assembled militia forces and used these troops to amass power outside of the collapsing imperial authority.[148]

General-in-chief He Jin (d. 189 AD), half-brother to Empress He (d. 189 AD), plotted with Yuan Shao (d. 202 AD) to overthrow the eunuchs by having several generals march to the outskirts of the capital. There, in a written petition to Empress He, they demanded the eunuchs' execution.[149] After a period of hesitation, Empress He consented. When the eunuchs discovered this, however, they had her brother He Miao (何苗) rescind the order.[150] The eunuchs assassinated He Jin on 22 September 189.

Yuan Shao then besieged Luoyang's Northern Palace while his brother Yuan Shu (d. 199 AD) besieged the Southern Palace. On September 25 both palaces were breached and approximately two thousand eunuchs were killed.[151][152] Zhang Rang had previously fled with Emperor Shao (r. 189 AD) and his brother Liu Xie—the future Emperor Xian of Han (r. 189–220 AD). While being pursued by the Yuan brothers, Zhang committed suicide by jumping into the Yellow River.[153]

General Dong Zhuo (d. 192 AD) found the young emperor and his brother wandering in the countryside. He escorted them safely back to the capital and was made Minister of Works, taking control of Luoyang and forcing Yuan Shao to flee.[154] After Dong Zhuo demoted Emperor Shao and promoted his brother Liu Xie as Emperor Xian, Yuan Shao led a coalition of former officials and officers against Dong, who burned Luoyang to the ground and resettled the court at Chang'an in May 191 AD. Dong Zhuo later poisoned Emperor Shao.[155]

Dong was killed by his adopted son Lü Bu (d. 198 AD) in a plot hatched by Wang Yun (d. 192 AD).[156] Emperor Xian fled from Chang'an in 195 AD to the ruins of Luoyang. Xian was persuaded by Cao Cao (155–220 AD), then Governor of Yan Province in modern western Shandong and eastern Henan, to move the capital to Xuchang in 196 AD.[157][158]

Yuan Shao challenged Cao Cao for control over the emperor. Yuan's power was greatly diminished after Cao defeated him at the Battle of Guandu in 200 AD. After Yuan died, Cao killed Yuan Shao's son Yuan Tan (173–205 AD), who had fought with his brothers over the family inheritance.[159][160] His brothers Yuan Shang and Yuan Xi were killed in 207 AD by Gongsun Kang (d. 221 AD), who sent their heads to Cao Cao.[159][160]

After Cao's defeat at the naval

Culture and society

Social class

In the hierarchical social order, the emperor was at the apex of Han society and government. However, the emperor was often a minor, ruled over by a regent such as the empress dowager or one of her male relatives.[165] Ranked immediately below the emperor were the kings who were of the same Liu family clan.[17][166] The rest of society, including nobles lower than kings and all commoners excluding slaves, belonged to one of twenty ranks (ershi gongcheng 二十公乘).

Each successive rank gave its holder greater pensions and legal privileges. The highest rank, of full

By the Eastern Han period, local elites of unattached scholars, teachers, students, and government officials began to identify themselves as members of a larger, nationwide

Farmers, more specifically small landowner–cultivators, were ranked just below scholars and officials in the social hierarchy. Other agricultural cultivators were of a lower status, such as

State-registered merchants, who were forced by law to wear white-colored clothes and pay high commercial taxes, were considered by the gentry as social parasites with a contemptible status.[178][179] These were often petty shopkeepers of urban marketplaces; merchants such as industrialists and itinerant traders working between a network of cities could avoid registering as merchants and were often wealthier and more powerful than the vast majority of government officials.[179][180]

Wealthy landowners, such as nobles and officials, often provided lodging for retainers who provided valuable work or duties, sometimes including fighting bandits or riding into battle. Unlike slaves, retainers could come and go from their master's home as they pleased.[181] Physicians, pig breeders, and butchers had fairly high social status, while occultist diviners, runners, and messengers had low status.[182][183]

Marriage, gender, and kinship

Right: a dog figurine found in a Han tomb wearing a decorative dog collar, indicating their domestication as pets.[184] Dog figurines are a common archaeological find in Han tombs,[185] while it is also known from written sources that the emperor's imperial parks had kennels for keeping hunting dogs.[186]

The Han-era family was

Marriages were highly ritualized, particularly for the wealthy, and included many important steps. The giving of betrothal gifts, known as bridewealth and dowry, were especially important. A lack of either was considered dishonorable and the woman would have been seen not as a wife, but as a concubine.[190] Arranged marriages were typical, with the father's input on his offspring's spouse being considered more important than the mother's.[191][192]

Monogamous marriages were also normal, although nobles and high officials were wealthy enough to afford and support concubines as additional lovers.[193][194] Under certain conditions dictated by custom, not law, both men and women were able to divorce their spouses and remarry.[195][196] However, a woman who had been widowed continued to belong to her husband's family after his death. In order to remarry, the widow would have to be returned to her family in exchange for a ransom fee. Her children would not be allowed to go with her.[190]

Right image: A Han pottery female dancer in silk robes

Apart from the passing of noble titles or ranks,

Women were expected to obey the will of their father, then their husband, and then their adult son in old age. However, it is known from contemporary sources that there were many deviations to this rule, especially in regard to mothers over their sons, and empresses who ordered around and openly humiliated their fathers and brothers.[201] Women were exempt from the annual corvée labor duties, but often engaged in a range of income-earning occupations aside from their domestic chores of cooking and cleaning.[202]

The most common occupation for women was weaving clothes for the family, for sale at market, or for large textile enterprises that employed hundreds of women. Other women helped on their brothers' farms or became singers, dancers, sorceresses, respected medical physicians, and successful merchants who could afford their own silk clothes.[203][204] Some women formed spinning collectives, aggregating the resources of several different families.[205]

Education, literature, and philosophy

The early Western Han court simultaneously accepted the philosophical teachings of

Unlike the original ideology espoused by

The Imperial University grew in importance as the student body grew to over 30,000 by the 2nd century CE.

Some important texts were created and studied by scholars. Philosophical works written by

Law and order

Han scholars such as Jia Yi (201–169 BC) portrayed the Qin as a brutal regime. However, archaeological evidence from Zhangjiashan and Shuihudi reveal that many of the statutes in the Han law code compiled by Chancellor Xiao He (d. 193 BC) were derived from Qin law.[233][234][235]

Various cases for rape, physical abuse, and murder were prosecuted in court. Women, although usually having fewer rights by custom, were allowed to level civil and criminal charges against men.

Acting as a judge in lawsuits was one of the many duties of the

Food

The most common staple crops consumed during Han were

Clothing

The types of clothing worn and the materials used during the Han period depended upon social class. Wealthy folk could afford

Religion, cosmology, and metaphysics

Families throughout Han China made ritual sacrifices of animals and food to deities, spirits, and ancestors at

In addition to his many other roles, the emperor acted as the highest priest in the land who made sacrifices to Heaven, the main deities known as the Five Powers, and spirits of mountains and rivers known as shen.[256] It was believed that the three realms of Heaven, Earth, and Mankind were linked by natural cycles of yin and yang and the five phases.[257][258][259][260] If the emperor did not behave according to proper ritual, ethics, and morals, he could disrupt the fine balance of these cosmological cycles and cause calamities such as earthquakes, floods, droughts, epidemics, and swarms of locusts.[260][261][262]

It was believed that immortality could be achieved if one reached the lands of the Queen Mother of the West or Mount Penglai.[263][264] Han-era Daoists assembled into small groups of hermits who attempted to achieve immortality through breathing exercises, sexual techniques, and the use of medical elixirs.[265]

By the 2nd century AD, Daoists formed large hierarchical religious societies such as the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice. Its followers believed that the sage-philosopher Laozi (fl. 6th century BC) was a holy prophet who would offer salvation and good health if his devout followers would confess their sins, ban the worship of unclean gods who accepted meat sacrifices, and chant sections of the Daodejing.[266]

Buddhism

Government and politics

Central government

In Han government, the emperor was the supreme judge and lawgiver, the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and sole designator of official nominees appointed to the top posts in central and local administrations; those who earned a 600-bushel salary-rank or higher.[271][272] Theoretically, there were no limits to his power.

However, state organs with competing interests and institutions such as the court conference (tingyi 廷議)—where ministers were convened to reach a majority consensus on an issue—pressured the emperor to accept the advice of his ministers on policy decisions.[273][274] If the emperor rejected a court conference decision, he risked alienating his high ministers. Nevertheless, emperors sometimes did reject the majority opinion reached at court conferences.[275]

Below the emperor were his

The Chancellor, whose title had changed in 8 BC to Minister over the Masses, was chiefly responsible for drafting the government budget. The Chancellor's other duties included managing provincial registers for land and population, leading court conferences, acting as judge in lawsuits, and recommending nominees for high office. He could appoint officials below the salary-rank of 600 bushels.[278][279]

The Imperial Counselor's chief duty was to conduct disciplinary procedures for officials. He shared similar duties with the Chancellor, such as receiving annual provincial reports. However, when his title was changed to Minister of Works in 8 BC, his chief duty became the oversight of public works projects.[280][281]

The Grand Commandant, whose title was changed to Grand Marshal in 119 BC before reverting to Grand Commandant in 51 AD, was the irregularly posted commander of the military and then regent during the Western Han period. In the Eastern Han era he was chiefly a civil official who shared many of the same censorial powers as the other two Councilors of State.[282][283]

Ranked below the Three Councillors of State were the Nine Ministers, who each headed a specialized ministry. The Minister of Ceremonies (Taichang 太常) was the chief official in charge of religious rites, rituals, prayers, and the maintenance of ancestral temples and altars.[284][285][286] The Minister of the Household (Guang lu xun 光祿勳) was in charge of the emperor's security within the palace grounds, external imperial parks, and wherever the emperor made an outing by chariot.[284][287]

The Minister of the Guards (Weiwei 衛尉) was responsible for securing and patrolling the walls, towers, and gates of the imperial palaces.

The Minister of the Imperial Clan (Zongzheng 宗正) oversaw the imperial court's interactions with the empire's nobility and extended imperial family, such as granting fiefs and titles.[296][297] The Minister of Finance (da sìnong 大司農) was the treasurer for the official bureaucracy and the armed forces who handled tax revenues and set standards for units of measurement.[298][299] The Minister Steward (Shaofu 少府) served the emperor exclusively, providing him with entertainment and amusements, proper food and clothing, medicine and physical care, valuables and equipment.[298][300]

Local government

The Han empire, excluding kingdoms and marquessates, was divided, in descending order of size, into political units of

The heads of provinces, whose official title was changed from Inspector to Governor and vice versa several times during Han, were responsible for inspecting several commandery-level and kingdom-level administrations.[304][305] On the basis of their reports, the officials in these local administrations would be promoted, demoted, dismissed, or prosecuted by the imperial court.[306]

A governor could take various actions without permission from the imperial court. The lower-ranked inspector had executive powers only during times of crisis, such as raising militias across the commanderies under his jurisdiction to suppress a rebellion.[301]

A commandery consisted of a group of counties, and was headed by an administrator.[301] He was the top civil and military leader of the commandery and handled defense, lawsuits, seasonal instructions to farmers, and recommendations of nominees for office sent annually to the capital in a quota system first established by Emperor Wu.[307][308][309] The head of a large county of about 10,000 households was called a Prefect, while the heads of smaller counties were called chiefs, and both could be referred to as magistrates.[310][311] A Magistrate maintained law and order in his county, registered the populace for taxation, mobilized commoners for annual corvée duties, repaired schools, and supervised public works.[311]

Kingdoms and marquessates

Kingdoms—roughly the size of

However, in 145 BC, after several insurrections by the kings, Emperor Jing removed the kings' rights to appoint officials whose salaries were higher than 400 bushels.[313] The Imperial Counselors and Nine Ministers (excluding the Minister Coachman) of every kingdom were abolished, although the Chancellor was still appointed by the central government.[313]

With these reforms, kings were reduced to being nominal heads of their fiefs, gaining a personal income from only a portion of the taxes collected in their kingdom.[17] Similarly, the officials in the administrative staff of a full marquess's fief were appointed by the central government. A marquess's Chancellor was ranked as the equivalent of a county Prefect. Like a king, the marquess collected a portion of the tax revenues in his fief as personal income.[310][315]

Until the reign of Emperor Jing of Han, the Han emperors had great difficulties controlling their vassal kings, who often switched allegiances to the Xiongnu whenever they felt threatened by imperial centralization of power. The seven years of Gaozu's reign featured defections by three vassal kings and one marquess, who then aligned themselves with the Xiongnu. Even imperial princes controlling fiefdoms would sometimes invite a Xiongnu invasion in response to the Emperor's threats. The Han moved to secure a treaty with the Xiongnu, aiming to clearly divide authority between them. The Han and Xiongnu now held one another out as the "two masters" with sole dominion over their respective peoples; they cemented this agreement with a marriage alliance (heqin), before eliminating the rebellious vassal kings in 154 BC. This prompted some of the Xiongnu vassals to swap allegiances to the Han, starting in 147. Han court officials were initially hostile to the idea of disrupting the status quo by expanding into Xiongnu territory in the steppe. The surrendered Xiongnu were integrated into a parallel military and political structures loyal to the Han emperor, a step toward a potential Han challenge to the superiority of Xiongnu cavalry in steppe warfare. This also brought the Han into contact with the interstate trade networks through the Tarim Basin in the far northwest, allowing for the Han's expansion from a regional state to a universalist, cosmopolitan empire achieved in part through further marriage alliances with the Wusun, another steppe power.[316]

Military

At the beginning of the Han dynasty, every male commoner aged twenty-three was liable for conscription into the military. The minimum age was reduced to twenty following the reign of Emperor Zhao (r. 87–74).[317] Conscripted soldiers underwent one year of training and one year of service as non-professional soldiers. The year of training was spent in one of three branches of the armed forces: infantry, cavalry, or navy. Prior to the abolition of much of the conscription system after 30 AD, soldiers could be called up for future service following the completion of their terms. They had to continue training regularly to maintain their skills, and were subject to annual inspections of their military readiness.[318][319] The year of active service was served either on the frontier, in a king's court, or in the capital under the Minister of the Guards. A small professional army was stationed near the capital.[318][319]

During the Eastern Han, conscription could be avoided if one paid a commutable tax. The Eastern Han court favored the recruitment of a volunteer army.[320] The volunteer army comprised the Southern Army (Nanjun 南軍), while the standing army stationed in and near the capital was the Northern Army (Beijun 北軍).[321] Led by Colonels (Xiaowei 校尉), the Northern Army consisted of five regiments, each composed of several thousand soldiers.[322][323] When central authority collapsed after 189 AD, wealthy landowners, members of the aristocracy/nobility, and regional military-governors relied upon their retainers to act as their own personal troops.[324]

During times of war, the volunteer army was increased, and a much larger militia was raised across the country to supplement the Northern Army. In these circumstances, a general (jiangjun 將軍) led a division, which was divided into regiments led by a colonel or major (sima 司馬). Regiments were divided into companies and led by captains. Platoons were the smallest units.[322][325]

Economy

Currency

The Han dynasty inherited the

In 144 BC Emperor Jing abolished private minting in favor of central-government and commandery-level minting; he also introduced a new coin.[327] Emperor Wu introduced another in 120 BC, but a year later he abandoned the ban liangs entirely in favor of the wuzhu coin, weighing 3.2 g (0.11 oz).[328] The wuzhu became China's standard coin until the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD). Its use was interrupted briefly by several new currencies introduced during Wang Mang's regime until it was reinstated in 40 AD by Emperor Guangwu.[329][330][331]

Since commandery-issued coins were often of inferior quality and lighter weight, the central government closed commandery mints and monopolized the issue of coinage in 113 BC. This central government issuance of coinage was overseen by the Superintendent of Waterways and Parks, this duty being transferred to the Minister of Finance during the Eastern Han.[331][332]

Taxation and property

Aside from the landowner's

The widespread circulation of coin cash allowed successful merchants to invest money in land, empowering the very social class the government attempted to suppress through heavy commercial and property taxes.[336] Emperor Wu even enacted laws which banned registered merchants from owning land, yet powerful merchants were able to avoid registration and own large tracts of land.[337][338]

The small landowner-cultivators formed the majority of the Han tax base; this revenue was threatened during the latter half of Eastern Han when many peasants fell into debt and were forced to work as farming tenants for wealthy landlords.[339][340][341] The Han government enacted reforms in order to keep small landowner-cultivators out of debt and on their own farms. These reforms included reducing taxes, temporary remissions of taxes, granting loans, and providing landless peasants temporary lodging and work in agricultural colonies until they could recover from their debts.[62][342]

In 168 BC, the land tax rate was reduced from one-fifteenth of a farming household's crop yield to one-thirtieth,[343][344] and later to one-hundredth of a crop yield for the last decades of the dynasty. The consequent loss of government revenue was compensated for by increasing property taxes.[344]

The labor tax took the form of conscripted labor for one month per year, which was imposed upon male commoners aged fifteen to fifty-six. This could be avoided in Eastern Han with a commutable tax, since hired labor became more popular.[318][345]

Private manufacture and government monopolies

In the early Western Han, a wealthy salt or iron industrialist, whether a semi-autonomous king or wealthy merchant, could boast funds that rivaled the imperial treasury and amass a peasant workforce numbering over 1000. This kept many peasants away from their farms and denied the government a significant portion of its land tax revenue.[346][347] To eliminate the influence of such private entrepreneurs, Emperor Wu nationalized the salt and iron industries in 117 BC and allowed many of the former industrialists to become officials administering the state monopolies.[348][349][350] By Eastern Han times, the central government monopolies were repealed in favor of production by commandery and county administrations, as well as private businessmen.[348][351]

Liquor was another profitable private industry nationalized by the central government in 98 BC. However, this was repealed in 81 BC and a property tax rate of two coins for every 0.2 litres (0.053 US gal) was levied for those who traded it privately.[352][353] By 110 BC, Emperor Wu also interfered with the profitable trade in grain when he eliminated speculation by selling government stores of grain at a lower price than that demanded by merchants.[62] Apart from Emperor Ming's creation of a short-lived Office for Price Adjustment and Stabilization, which was abolished in 68 AD, central-government price control regulations were largely absent during the Eastern Han.[354]

Science and technology

The Han dynasty was a unique period in the development of premodern Chinese science and technology, comparable to the level of

Writing materials

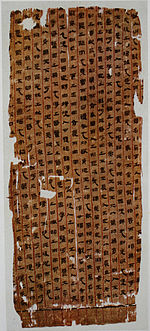

In the 1st millennium BC, typical ancient Chinese writing materials were

The oldest known Chinese piece of hempen paper dates to the 2nd century BC.[363][358] The standard papermaking process was invented by Cai Lun (AD 50–121) in 105.[364][365] The oldest known surviving piece of paper with writing on it was found in the ruins of a Han watchtower that had been abandoned in AD 110, in Inner Mongolia.[366]

Metallurgy and agriculture

Right image: A pair of Eastern-Han iron scissors

Evidence suggests that blast furnaces, that convert raw iron ore into pig iron, which can be remelted in a cupola furnace to produce cast iron by means of a cold blast and hot blast, were operational in China by the late Spring and Autumn period (722–481 BC).[367][368] The bloomery was nonexistent in ancient China; however, the Han-era Chinese produced wrought iron by injecting excess oxygen into a furnace and causing decarburization.[369] Cast iron and pig iron could be converted into wrought iron and steel using a fining process.[370][371]

The Han dynasty Chinese used bronze and iron to make a range of weapons, culinary tools, carpenters' tools, and domestic wares.[372][373] A significant product of these improved iron-smelting techniques was the manufacture of new agricultural tools. The three-legged iron seed drill, invented by the 2nd century BC, enabled farmers to carefully plant crops in rows instead of sowing seeds by hand.[374][375][376] The heavy moldboard iron plow, also invented during the Han dynasty, required only one man to control it with two oxen to pull it. It had three plowshares, a seed box for the drills, a tool which turned down the soil and could sow roughly 45,730 m2 (11.3 acres) of land in a single day.[377][378]

To protect crops from wind and drought, the grain intendant Zhao Guo (趙過) created the alternating fields system (daitianfa 代田法) during Emperor Wu's reign. This system switched the positions of ridges and furrows between growing seasons.[379] Once experiments with this system yielded successful results, the government officially sponsored it and encouraged peasants to use it.[379] Han farmers also used the pit field system (aotian 凹田) for growing crops, which involved heavily fertilized pits that did not require plows or oxen and could be placed on sloping terrain.[380][381] In the southern and small parts of central Han-era China, paddy fields were chiefly used to grow rice, while farmers along the Huai River used transplantation methods of rice production.[382]

Structural and geotechnical engineering

Right image: A painted ceramic architectural model—found in an Eastern-Han tomb at Jiazuo, Henan province—depicting a fortified manor with towers, a courtyard, verandas, tiled rooftops, dougong support brackets, and a covered bridge extending from the third floor of the main tower to the smaller watchtower.[384]

Right image: A Han-dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) era pottery model of a granary tower with windows and balcony placed several stories above the first-floor courtyard; Zhang Heng (78–139 AD) described the large imperial park in the suburbs of Chang'an as having tall towers where archers would shoot stringed arrows from the top in order to entertain the Western Han emperors.[385]

Timber was the chief building material during the Han dynasty; it was used to build palace halls, multi-story residential towers and halls, and single-story houses.[386] Because wood decays rapidly, the only remaining evidence of Han wooden architecture is a collection of scattered ceramic roof tiles.[386][387] The oldest surviving wooden halls in China date to the Tang dynasty (618–907).[388] Architectural historian Robert L. Thorp points out the scarcity of Han-era archeological remains, and claims that often unreliable Han-era literary and artistic sources are used by historians for clues about lost Han architecture.[389]

Though Han wooden structures decayed, some Han-dynasty ruins made of brick, stone, and

The courtyard house is the most common type of home portrayed in Han artwork.[386] Ceramic architectural models of buildings, like houses and towers, were found in Han tombs, perhaps to provide lodging for the dead in the afterlife. These provide valuable clues about lost wooden architecture. The artistic designs found on ceramic roof tiles of tower models are in some cases exact matches to Han roof tiles found at archeological sites.[397]

Over ten Han-era underground tombs have been found, many of them featuring archways, vaulted chambers, and domed roofs.[398] Underground vaults and domes did not require buttress supports since they were held in place by earthen pits.[399] The use of brick vaults and domes in aboveground Han structures is unknown.[399]

From Han literary sources, it is known that wooden-trestle beam bridges, arch bridges, simple suspension bridges, and floating pontoon bridges existed in Han China.[400] However, there are only two known references to arch bridges in Han literature.[401] There is only one relief sculpture dated to the Han period that depicts an arch bridge; it is located in Sichuan province.[402]

-

A pair of stone-carved que (闕) located at the temple of Mount Song in Dengfeng. (Eastern Han dynasty.)

-

A pair of Han period stone-carved que (闕) located at Babaoshan, Beijing.

Mechanical and hydraulic engineering

Han-era mechanical engineering comes largely from the choice observational writings of sometimes-disinterested Confucian scholars who generally considered scientific and engineering endeavors to be far beneath them.[408] Professional artisan-engineers (jiang 匠) did not leave behind detailed records of their work.[409][d] Han scholars, who often had little or no expertise in mechanical engineering, sometimes provided insufficient information on the various technologies they described.[410] Nevertheless, some Han literary sources provide crucial information.

For example, in 15 BC the philosopher and poet Yang Xiong described the invention of the belt drive for a quilling machine, which was of great importance to early textile manufacturing.[411] The inventions of mechanical engineer and craftsman Ding Huan are mentioned in the Miscellaneous Notes on the Western Capital.[412] Around AD 180, Ding created a manually operated rotary fan used for air conditioning within palace buildings.[413] Ding also used gimbals as pivotal supports for one of his incense burners and invented the world's first known zoetrope lamp.[414]

Modern archeology has led to the discovery of Han artwork portraying inventions which were otherwise absent in Han literary sources. As observed in Han miniature tomb models, but not in literary sources, the

Modern archeologists have also unearthed specimens of devices used during the Han dynasty, for example a pair of sliding metal

The

The

Zhang also invented a device he termed an "earthquake weathervane" (houfeng didong yi 候風地動儀), which the British sinologist and historian

Mathematics

Three Han mathematical treatises still exist. These are the

One of the Han's greatest mathematical advancements was the world's first use of negative numbers. Negative numbers first appeared in the Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art as black counting rods, where positive numbers were represented by red counting rods.[435] Negative numbers were also used by the Greek mathematician Diophantus around AD 275, and in the 7th-century Bakhshali manuscript of Gandhara, South Asia,[445] but were not widely accepted in Europe until the 16th century.[435]

The Han applied mathematics to various diverse disciplines. In

Astronomy

Mathematics were essential in drafting the astronomical calendar, a lunisolar calendar that used the Sun and Moon as time-markers throughout the year.[448][449] During the spring and autumn periods of the 5th century BC, the Chinese established the Sifen calendar (古四分歷), which measured the tropical year at 365.25 days. This was replaced in 104 BC with the Taichu calendar (太初曆) that measured the tropical year at 365+385⁄1539 (~ 365.25016) days and the lunar month at 29+43⁄81 days.[450] However, Emperor Zhang later reinstated the Sifen calendar.[451]

Han dynasty astronomers made star catalogues and detailed records of comets that appeared in the night sky, including recording the 12 BC appearance of the comet now known as Halley's Comet.[452][453][454][455] They adopted a geocentric model of the universe, theorizing that it was shaped like a sphere surrounding the Earth in the center.[456][457][458] They assumed that the Sun, Moon, and planets were spherical and not disc-shaped. They also thought that the illumination of the Moon and planets was caused by sunlight, that lunar eclipses occurred when the Earth obstructed sunlight falling onto the Moon, and that a solar eclipse occurred when the Moon obstructed sunlight from reaching the Earth.[459] Although others disagreed with his model, Wang Chong accurately described the water cycle of the evaporation of water into clouds.[460]

Cartography, ships, and vehicles

Evidence found in Chinese literature, and archeological evidence, show that cartography existed in China before the Han.[461][462] Some of the earliest Han maps discovered were ink-penned silk maps found amongst the Mawangdui Silk Texts in a 2nd-century-BC tomb.[461][463] The general Ma Yuan created the world's first known raised-relief map from rice in the 1st century.[464] This date could be revised if the tomb of Emperor Qin Shi Huang is excavated and the account in the Records of the Grand Historian concerning a model map of the empire is proven to be true.[465]

Although the use of the

Han dynasty Chinese sailed in a variety of ships different from those of previous eras, such as the

Although ox-carts and chariots were previously used in China, the wheelbarrow was first used in Han China in the 1st century BC.[476][477] Han artwork of horse-drawn chariots shows that the Warring-States-Era heavy wooden yoke placed around a horse's chest was replaced by the softer breast strap.[478] Later, during the Northern Wei (386–534), the fully developed horse collar was invented.[478]

Medicine

Han-era medical physicians believed that the human body was subject to the same forces of nature that governed the greater universe, namely the

For example, since the wood phase was believed to promote the fire phase, medicinal ingredients associated with the wood phase could be used to heal an organ associated with the fire phase.

See also

- Battle of Jushi

- Campaign against Dong Zhuo

- Comparative studies of the Roman and Han empires

- Han Emperors family tree

- Shuanggudui

- Ten Attendants

Notes

- ^ See also Hinsch (2002), pp. 21–22

- ^ See also Needham (1972), p. 112.

- ^ See also Ebrey (1999), p. 76; see Needham (1972), Plate V, Fig. 15, for a photo of a Han-era fortress in Dunhuang, Gansu province that has rammed earth ramparts with defensive crenellations at the top.

- ^ See also Barbieri-Low (2007), p. 36.

References

Citations

- ^ Barnes (2007), p. 63.

- ^ a b Taagepera (1979), p. 128.

- ^ a b Nishijima (1986), pp. 595–596.

- ISBN 978-0-008-28437-4.

- ^ "Han". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins.

- ^ Zhou (2003), p. 34.

- ^ Schaefer (2008), p. 279.

- ^ Bailey (1985), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Loewe (1986), p. 116.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 60–61.

- ^ Loewe (1986), pp. 116–122.

- ^ Davis (2001), pp. 44–46.

- ^ Loewe (1986), p. 122.

- ^ a b Loewe (1986), pp. 122–125.

- ^ Loewe (1986), pp. 139–144.

- ^ a b Bielenstein (1980), p. 106.

- ^ a b c d Ch'ü (1972), p. 76.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 105.

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 175–189, 196–198.

- ^ Torday (1997), pp. 80–81.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 387–388.

- ^ a b Torday (1997), pp. 75–77.

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 190–192.

- ^ Yü (1967), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Morton & Lewis (2005), p. 52.

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 192–195.

- ^ Qingbo (2023).

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 388–389.

- ^ Torday (1997), pp. 77, 82–83.

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 195–196.

- ^ Torday (1997), pp. 83–84.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 389–390.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 389–391.

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 211–214.

- ^ Torday (1997), pp. 91–92.

- ^ Yü (1986), p. 390.

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 237–240.

- ^ Loewe (1986), pp. 196–197, 211–213.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 395–398.

- ^ Chang (2007), pp. 5–8.

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 241–242.

- ^ Yü (1986), p. 391.

- ^ Chang (2007), pp. 34–35.

- ^ Chang (2007), pp. 6, 15–16, 44–45.

- ^ Chang (2007), pp. 15–16, 33–35, 42–43.

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 247–249.

- ^ Morton & Lewis (2005), pp. 54–55.

- ^ Yü (1986), p. 407.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 69.

- ^ Torday (1997), pp. 104–117.

- ^ An (2002), p. 83.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 70.

- ^ Di Cosmo (2002), pp. 250–251.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 390–391, 409–411.

- ^ Chang (2007), p. 174.

- ^ Loewe (1986), p. 198.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 83.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 448–453.

- ^ Wagner (2001), pp. 1–17.

- ^ Loewe (1986), pp. 160–161.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 581–588.

- ^ a b c Ebrey (1999), p. 75.

- ^ Morton & Lewis (2005), p. 57.

- ^ Loewe (1986), pp. 162, 185–206.

- ^ Paludan (1998), p. 41.

- ^ Wagner (2001), pp. 16–19.

- ^ Wang, Li & Zhang (2010), pp. 351–352.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 225–226.

- ^ Huang (1988), pp. 46–48.

- ^ a b c Bielenstein (1986), pp. 227–230.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), pp. 23–24.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b Ebrey (1999), p. 66.

- ^ Hansen (2000), p. 134.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 232–234.

- ^ Morton & Lewis (2005), p. 58.

- ^ Lewis (2007), p. 23.

- ^ a b Hansen (2000), p. 135.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 196.

- ^ a b Bielenstein (1986), pp. 241–244.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 568.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), p. 248.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 197, 560.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 249–250.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 558–560.

- ^ a b Bielenstein (1986), pp. 251–254.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 196–198, 560.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 54–55, 269–270, 600–601.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 254–255.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Knechtges (2010), p. 116.

- ^ Yü (1986), p. 450.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 562, 660.

- ^ Yü (1986), p. 454.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 237–238.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 399–400.

- ^ Psarras (2015), p. 19.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 413–414.

- ^ a b c Yü (1986), pp. 414–415.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 73.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 171.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 405, 443–444.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 444–446.

- ^ Cribb (1978), pp. 76–78.

- ^ a b Torday (1997), p. 393.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 415–416.

- ^ Akira (1998), pp. 248, 251.

- ^ Zhang (2002), p. 75.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 239–240, 497, 590.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 450–451, 460–461.

- ^ Chavannes (1907), p. 185.

- ^ a b Hill (2009), p. 27.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 600.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 460–461.

- ^ An (2002), pp. 83–84.

- ^ a b Ball (2016), p. 153.

- ^ Young (2001), pp. 83–84.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 52.

- ^ Young (2001), p. 29.

- ^ Mawer (2013), p. 38.

- ^ Suárez (1999), p. 92.

- ^ O'Reilly (2007), p. 97.

- ^ Bi (2019).

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 497, 500, 592.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), p. 25.

- ^ Hansen (2000), p. 136.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 280–283.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 499, 588–589.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 283–284.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 123–127.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), p. 284.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 128, 580.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 284–285.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 473–474, 582–583.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 285–286.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 597–598.

- ^ Hansen (2000), p. 141.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 597, 599, 601–602.

- ^ a b Hansen (2000), pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 602.

- ^ Beck (1986), pp. 319–322.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 511.

- ^ Beck (1986), p. 323.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 513–514.

- ^ Ebrey (1986), pp. 628–629.

- ^ Beck (1986), pp. 339–340.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 84.

- ^ Beck (1986), pp. 339–344.

- ^ Beck (1986), p. 344.

- ^ Beck (1986), pp. 344–345.

- ^ Morton & Lewis (2005), p. 62.

- ^ Beck (1986), p. 345.

- ^ Beck (1986), pp. 345–346.

- ^ Beck (1986), pp. 346–349.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 158.

- ^ Beck (1986), pp. 349–351.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 36.

- ^ a b Beck (1986), pp. 351–352.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Beck (1986), p. 352.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 37.

- ^ Beck (1986), pp. 353–357.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), p. 206.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 66–72.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 105–107.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 552–553.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), p. 16.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), p. 84.

- ^ Ebrey (1986), pp. 631, 643–644.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), p. 80.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 601–602.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 104–111.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 556–557.

- ^ Ebrey (1986), pp. 621–622.

- ^ Ebrey (1974), pp. 173–174.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), p. 112.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 104–105, 119–120.

- ^ a b Nishijima (1986), pp. 576–577.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 114–117.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 127–128.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi (2006), pp. 172–173, 179–180.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 106, 122–127.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 57, 203.

- ^ Eiland (2003), p. 77.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 83.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), pp. 46–47.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 3–9.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Wiesner-Hanks (2011), p. 30.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), p. 35.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), p. 34.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 44–47.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), pp. 40–45.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 37–43.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 6–9.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 17–18.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), p. 17.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 49–59.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 54–56.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), pp. 29, 51, 54, 59–60, 65–68, 70–74, 77–78.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), p. 29.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi (2006), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Loewe (1994), pp. 128–130.

- ^ Kramers (1986), pp. 754–756.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi (2006), pp. 7–8.

- ^ Loewe (1994), pp. 121–125.

- ^ Ch'en (1986), p. 769.

- ^ Kramers (1986), pp. 753–755.

- ^ Loewe (1994), pp. 134–140.

- ^ Kramers (1986), p. 754.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Kramers (1986), p. 757.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), p. 103.

- ISBN 9780521196208.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 513.

- ^ Barbieri-Low (2007), p. 207.

- ^ Huang (1988), p. 57.

- ^ Ch'en (1986), pp. 773–794.

- ^ Hardy (1999), pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b Hansen (2000), pp. 137–138.

- ^ Ebrey (1986), p. 645.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 185.

- ^ Xue (2003), p. 161.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 1049.

- ^ Neinhauser et al. (1986), p. 212.

- ^ Lewis (2007), p. 222.

- ^ Cutter (1989), pp. 25–26.

- ^ Hansen (2000), pp. 117–119.

- ^ Hulsewé (1986), pp. 525–526.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi (2006), pp. 23–24.

- ^ Hansen (2000), pp. 110–112.

- ^ Hulsewé (1986), pp. 523–530.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), p. 82.

- ^ Hulsewé (1986), pp. 532–535.

- ^ Hulsewé (1986), pp. 531–533.

- ^ Hulsewé (1986), pp. 528–529.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 552–553, 576.

- ^ Loewe (1968), pp. 146–147.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 83–85.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 581–583.

- ^ Wang (1982), p. 52.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 53, 206.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 57–58.

- ^ Hansen (2000), pp. 119–121.

- ^ Wang (1982), p. 206.

- ^ a b Hansen (2000), p. 119.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 53, 59–63, 206.

- ^ Loewe (1968), p. 139.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), p. 128.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 30–31.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi (2006), pp. 140–141.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), p. 71.

- ^ Loewe (1994), p. 55.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi (2006), p. 167.

- ^ Sun & Kistemaker (1997), pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Ebrey (1999), pp. 78–79.

- ^ Loewe (1986), p. 201.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 496, 592.

- ^ Loewe (2005), pp. 101–102.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi (2006), pp. 116–117.

- ^ Hansen (2000), p. 144.

- ^ Hansen (2000), pp. 144–146.

- ^ Needham (1972), p. 112.

- ^ a b Demiéville (1986), pp. 821–822.

- ^ Demiéville (1986), p. 823.

- ^ Akira (1998), pp. 247–251.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 1216.

- ^ Wang (1949), pp. 141–143.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 144.

- ^ Wang (1949), pp. 173–177.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 70–71.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 1221.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 7–17.

- ^ Wang (1949), pp. 143–144, 145–146, 177.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 7–8, 14.

- ^ Wang (1949), pp. 147–148.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 8–9, 15–16.

- ^ Wang (1949), p. 150.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 10–13.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 1222.

- ^ Wang (1949), p. 151.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 17–23.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 23–24.

- ^ Loewe (1994), pp. 38–52.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 1223.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 31.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 34–35.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 38.

- ^ Wang (1949), p. 154.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 1223–1224.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 39–40.

- ^ Wang (1949), p. 155.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 41.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 1224.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 43.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 47.

- ^ a b c de Crespigny (2007), p. 1228.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 103.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 551–552.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 90–92.

- ^ Wang (1949), pp. 158–160.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 91.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 1230–1231.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 96.

- ^ Hsu (1965), pp. 367–368.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 1230.

- ^ a b Bielenstein (1980), p. 100.

- ^ a b Hsu (1965), p. 360.

- ^ a b c d Bielenstein (1980), pp. 105–106.

- ^ Loewe (1986), p. 126.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), p. 108.

- ^ Lewis & Hsieh (2017), pp. 32–39.

- ^ Chang (2007), pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c Nishijima (1986), p. 599.

- ^ a b Bielenstein (1980), p. 114.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 564–565, 1234.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 114–115.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 1234.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 117–118.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 132–133.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 116, 120–122.

- ^ a b Nishijima (1986), p. 586.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 586–587.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), p. 587.

- ^ Ebrey (1986), p. 609.

- ^ Bielenstein (1986), pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b Nishijima (1986), pp. 587–588.

- ^ Bielenstein (1980), pp. 47, 83.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 600–601.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), p. 598.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), p. 588.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), p. 601.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), p. 577.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 113–114.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 558–601.

- ^ Ebrey (1974), pp. 173 174.

- ^ Ebrey (1999), pp. 74–75.

- ^ Ebrey (1986), pp. 619–621.

- ^ Loewe (1986), pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b Nishijima (1986), pp. 596–598.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), pp. 564–565.

- ^ Needham (1986c), p. 22.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 583–584.

- ^ a b Nishijima (1986), p. 584.

- ^ Wagner (2001), pp. 1–2.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Wagner (2001), pp. 15–17.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), p. 600.

- ^ Wagner (2001), pp. 13–14.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 605.

- ^ Wang (1982), p. 100.

- ^ Jin, Fan & Liu (1996), pp. 178–179.

- ^ Needham (1972), p. 111.

- ^ a b Needham & Tsien (1986), p. 38.

- ^ Li (1974).

- ^ Loewe (1968), pp. 89, 94–95.

- ^ Tom (1989), p. 99.

- ^ Cotterell (2004), pp. 11–13.

- ^ Buisseret (1998), p. 12.

- ^ Needham & Tsien (1986), pp. 1–2, 40–41, 122–123, 228.

- ^ Day & McNeil (1996), p. 122.

- ^ Cotterell (2004), p. 11.

- ^ Wagner (2001), pp. 7, 36–37, 64–68, 75–76.

- ^ Pigott (1999), pp. 183–184.

- ^ Pigott (1999), pp. 177, 191.

- ^ Wang (1982), p. 125.

- ^ Pigott (1999), p. 186.

- ^ Wagner (1993), p. 336.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 103–105, 122–124.

- ^ Greenberger (2006), p. 12.

- ^ Cotterell (2004), p. 24.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 54–55.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 563–564.

- ^ Ebrey (1986), pp. 616–617.

- ^ a b Nishijima (1986), pp. 561–563.

- ^ Hinsch (2002), pp. 67–68.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 564–566.

- ^ Nishijima (1986), pp. 568–572.

- ^ Ch'ü (1972), pp. 68–69.

- ^ Guo (2005), pp. 46–48.

- ^ Bulling (1962), p. 312.

- ^ a b c Ebrey (1999), p. 76.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 1–40.

- ^ Steinhardt (2004), pp. 228–238.

- ^ Thorp (1986), pp. 360–378.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 1, 30, 39–40, 148–149.

- ^ Chang (2007), pp. 91–92.

- ^ Morton & Lewis (2005), p. 56.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 1–39.

- ^ Steinhardt (2005a), p. 279.

- ^ a b c Liu (2002), p. 55.

- ^ Steinhardt (2005a), pp. 279–280.

- ^ Steinhardt (2005b), pp. 283–284.

- ^ Wang (1982), pp. 175–178.

- ^ a b Watson (2000), p. 108.

- ^ Needham (1986d), pp. 161–188.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 171–172.

- ^ Liu (2002), p. 56.

- ^ a b Loewe (1968), pp. 191–194.

- ^ Wang (1982), p. 105.

- ^ Tom (1989), p. 103.

- ^ Ronan (1994), p. 91.

- ^ Loewe (1968), pp. 193–194.

- ^ Fraser (2014), p. 370.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 2, 9.

- ^ Needham (1986c), p. 2.

- ^ Needham (1988), pp. 207–208.

- ^ Barbieri-Low (2007), p. 197.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 99, 134, 151, 233.

- ^ Needham (1986b), pp. 123, 233–234.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 116–119, Plate CLVI.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 281–285.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 283–285.

- ^ Loewe (1968), pp. 195–196.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 183–184, 390–392.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 396–400.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 184.

- ^ Needham (1986c), p. 370.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 89, 110, 342–344.

- ^ Needham (1986a), p. 343.

- ^ a b c d de Crespigny (2007), p. 1050.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 30, 479 footnote e.

- ^ a b Morton & Lewis (2005), p. 70.

- ^ Bowman (2000), p. 595.

- ^ Needham (1986c), p. 479 footnote e.

- ^ Cited in Fraser (2014), p. 375.

- ^ Fraser (2014), p. 375.

- ^ Needham (1986a), pp. 626–631.

- ^ Fraser (2014), p. 376.

- ^ Dauben (2007), p. 212.

- ^ a b c Liu et al. (2003), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Needham (1986a), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Berggren, Borwein & Borwein (2004), p. 27.

- ^ Dauben (2007), pp. 219–222.

- ^ Needham (1986a), p. 22.

- ^ Needham (1986a), pp. 84–86

- ^ Shen, Crossley & Lun (1999), p. 388.

- ^ Straffin (1998), p. 166.

- ^ Needham (1986a), pp. 24–25, 121.

- ^ Needham (1986a), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Teresi (2002), pp. 65–66.

- ^ McClain & Ming (1979), p. 212.

- ^ Needham (1986b), pp. 218–219.

- ^ Cullen (2006), p. 7.

- ^ Lloyd (1996), p. 168.

- ^ Deng (2005), p. 67.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 498.

- ^ Loewe (1994), pp. 61, 69.

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi (2006), pp. 173–175.

- ^ Sun & Kistemaker (1997), pp. 5, 21–23.

- ^ Balchin (2003), p. 27.

- ^ Dauben (2007), p. 214.

- ^ Sun & Kistemaker (1997), p. 62.

- ^ Huang (1988), p. 64.

- ^ Needham (1986a), pp. 227, 414.

- ^ Needham (1986a), p. 468.

- ^ a b c Hsu (1993), pp. 90–93.

- ^ Needham (1986a), pp. 534–535.

- ^ Hansen (2000), p. 125.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 659.

- ^ Needham (1986a), pp. 580–581.

- ^ Needham (1986a), pp. 538–540.

- ^ Nelson (1974), p. 359.

- ^ Turnbull (2002), p. 14.

- ^ Needham (1986d), pp. 390–391.

- ^ Needham (1986d), pp. 627–628.

- ^ Chung (2005), p. 152.

- ^ Tom (1989), pp. 103–104.

- ^ Adshead (2000), p. 156.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman (1998), p. 93.

- ^ Block (2003), pp. 93, 123.

- ^ Needham (1986c), pp. 263–267.

- ^ Greenberger (2006), p. 13.

- ^ a b Needham (1986c), pp. 308–312, 319–323.

- ^ a b Csikszentmihalyi (2006), pp. 181–182.

- ^ Sun & Kistemaker (1997), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Hsu (2001), p. 75.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 332.

- ^ Omura (2003), pp. 15, 19–22.

- ^ Loewe (1994), p. 65.

- ^ Lo (2001), p. 23.

- ^ de Crespigny (2007), p. 1055.

Sources cited

- Adshead, Samuel Adrian Miles (2000), China in World History, London: MacMillan Press, ISBN 978-0-312-22565-0.

- Akira, Hirakawa (1998), A History of Indian Buddhism: From Sakyamani to Early Mahayana, translated by Paul Groner, New Delhi: Jainendra Prakash Jain at Shri Jainendra Press, ISBN 978-81-208-0955-0.

- An, Jiayao (2002), "When glass was treasured in China", in Juliano, Annette L.; Lerner, Judith A. (eds.), Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road, Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 79–94, ISBN 978-2-503-52178-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-11992-4.

- Balchin, Jon (2003), Science: 100 Scientists Who Changed the World, New York: Enchanted Lion Books, ISBN 978-1-59270-017-2.

- ISBN 978-0-415-72078-6.

- Barbieri-Low, Anthony J. (2007), Artisans in Early Imperial China, Seattle & London: University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98713-2.

- Barnes, Ian (2007), Mapping History: World History, London: Cartographica, ISBN 978-1-84573-323-0.

- Beck, Mansvelt (1986), "The fall of Han", in ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Berggren, Lennart; Borwein, Jonathan M.; Borwein, Peter B. (2004), Pi: A Source Book, New York: Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-20571-7.

- Bi, Zhicheng (2019). "Stone Reliefs of the Han Tombs in Shandong Province: Relationship Between Motifs and Composition" (PDF). Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. 368: 175–177.

- ISBN 978-0-521-22510-6.

- ——— (1986), "Wang Mang, the Restoration of the Han Dynasty, and Later Han", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 223–290, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Block, Leo (2003), To Harness the Wind: A Short History of the Development of Sails, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-55750-209-4.

- Bower, Virginia (2005), "Standing man and woman", in Richard, Naomi Noble (ed.), Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines', New Haven and London: ISBN 978-0-300-10797-5.

- Bowman, John S. (2000), Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-11004-4.

- Buisseret, David (1998), Envisioning the City: Six Studies in Urban Cartography, Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-07993-6.

- Bulling, A. (1962), "A landscape representation of the Western Han period", Artibus Asiae, 25 (4): 293–317, JSTOR 3249129.

- Chang, Chun-shu (2007), The Rise of the Chinese Empire: Volume II; Frontier, Immigration, & Empire in Han China, 130 B.C. – A.D. 157, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-11534-1.

- Chavannes, Édouard (1907), "Les pays d'Occident d'après le Heou Han chou" (PDF), T'oung Pao, 8: 149–244, (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022.

- Ch'en, Ch'i-Yün (1986), "Confucian, Legalist, and Taoist thought in Later Han", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 766–806, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Ch'ü, T'ung-tsu (1972), Dull, Jack L. (ed.), Han Dynasty China: Volume 1: Han Social Structure, Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-95068-6.

- Chung, Chee Kit (2005), "Longyamen is Singapore: The Final Proof?", Admiral Zheng He & Southeast Asia, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-981-230-329-5.

- Cotterell, Maurice (2004), The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army, Rochester: Bear and Company, ISBN 978-1-59143-033-9.

- Cribb, Joe (1978), "Chinese lead ingots with barbarous Greek inscriptions", Coin Hoards, 4: 76–78, archived from the original on 16 August 2021, retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mark (2006), Readings in Han Chinese Thought, Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-87220-710-3.

- Cullen, Christoper (2006), Astronomy and Mathematics in Ancient China: The Zhou Bi Suan Jing, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-03537-8.

- Cutter, Robert Joe (1989), The Brush and the Spur: Chinese Culture and the Cockfight, Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong, ISBN 978-962-201-417-6.

- ISBN 978-0-691-11485-9.

- ISBN 978-0-19-514366-9.

- Day, Lance; McNeil, Ian (1996), Biographical Dictionary of the History of Technology, New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-06042-4.

- ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- Demiéville, Paul (1986), "Philosophy and religion from Han to Sui", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 808–872, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Deng, Yingke (2005), Ancient Chinese Inventions, translated by Wang Pingxing, Beijing: China Intercontinental Press (五洲传播出版社), ISBN 978-7-5085-0837-5.

- ISBN 978-0-521-77064-4.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1974), "Estate and family management in the Later Han as seen in the Monthly Instructions for the Four Classes of People", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 17 (2): 173–205, JSTOR 3596331.

- ——— (1986), "The Economic and Social History of Later Han", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 608–648, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ——— (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66991-7.

- Eiland, Murray (2003), "Looking at Ancient Chinese Dogs Looking at Ancient Chinese Dogs", Athena Review, 3 (3): 75–79.

- ISBN 978-0-674-11673-3.

- Fraser, Ian W. (2014), "Zhang Heng 张衡", in Brown, Kerry (ed.), The Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography, Great Barrington: Berkshire Publishing, ISBN 978-1-933782-66-9.

- Greenberger, Robert (2006), The Technology of Ancient China, New York: Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1-4042-0558-1.

- Guo, Qinghua (2005), Chinese Architecture and Planning: Ideas, Methods, and Techniques, Stuttgart and London: Edition Axel Menges, ISBN 978-3-932565-54-0.

- ISBN 978-0-393-97374-7.

- Hardy, Grant (1999), Worlds of Bronze and Bamboo: Sima Qian's Conquest of History, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-11304-5.

- Hill, John E. (2009), Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries AD, Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge, ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hinsch, Bret (2002), Women in Imperial China, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, ISBN 978-0-7425-1872-8.

- S2CID 146695190.

- Hsu, Elisabeth (2001), "Pulse diagnostics in the Western Han: how mai and qi determine bing", in Hsu, Elisabeth (ed.), Innovations in Chinese Medicine, Cambridge, New York, Oakleigh, Madrid, and Cape Town: Cambridge University Press, pp. 51–92, ISBN 978-0-521-80068-6.

- Hsu, Mei-ling (1993), "The Qin maps: a clue to later Chinese cartographic development", Imago Mundi, 45: 90–100, .

- ISBN 978-0-87332-452-6.

- ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Jin, Guantao; Fan, Hongye; Liu, Qingfeng (1996), "Historical Changes in the Structure of Science and Technology (Part Two, a Commentary)", in Dainian, Fan; Cohen, Robert S. (eds.), Chinese Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, translated by Kathleen Dugan and Jiang Mingshan, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 165–184, ISBN 978-0-7923-3463-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-85558-7.

- Kramers, Robert P. (1986), "The development of the Confucian schools", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 747–756, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9.

- Lewis, Mark Edward; Hsieh, Mei-yu (2017). "Tianxia and the invention of empire in East Asia". In Wang, Ban (ed.). Chinese Visions of World Order: Tianxia, Culture, and World Politics. Duke University Press. pp. 25–48. JSTOR j.ctv11cw3gv.

- Li, Hui-Lin (1974). "An archeological and historical account of cannabis in China". Economic Botany. 28 (4): 437–448. S2CID 19866569.

- Liu, Xujie (2002), "The Qin and Han dynasties", in Steinhardt, Nancy S. (ed.), Chinese Architecture, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 33–60, ISBN 978-0-300-09559-3.

- Liu, Guilin; Feng, Lisheng; Jiang, Airong; Zheng, Xiaohui (2003), "The Development of E-Mathematics Resources at Tsinghua University Library (THUL)", in Bai, Fengshan; Wegner, Bern (eds.), Electronic Information and Communication in Mathematics, Berlin, Heidelberg and New York: Springer Verlag, pp. 1–13, ISBN 978-3-540-40689-1.

- ISBN 978-0-521-55695-8.

- Lo, Vivienne (2001), "The influence of nurturing life culture on the development of Western Han acumoxa therapy", in Hsu, Elisabeth (ed.), Innovation in Chinese Medicine, Cambridge, New York, Oakleigh, Madrid and Cape Town: Cambridge University Press, pp. 19–50, ISBN 978-0-521-80068-6.

- ISBN 978-0-87220-758-5.

- ——— (1986), "The Former Han Dynasty", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 103–222, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ——— (1994), Divination, Mythology and Monarchy in Han China, Cambridge, New York and Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-45466-7.

- ——— (2005), "Funerary Practice in Han Times", in Richard, Naomi Noble (ed.), Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines', New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 23–74, ISBN 978-0-300-10797-5.

- Mawer, Granville Allen (2013), "The Riddle of Cattigara", in Robert Nichols and Martin Woods (ed.), Mapping Our World: Terra Incognita to Australia, Canberra: National Library of Australia, pp. 38–39, ISBN 978-0-642-27809-8.

- McClain, Ernest G.; Ming, Shui Hung (1979), "Chinese cyclic tunings in late antiquity", Ethnomusicology, 23 (2): 205–224, JSTOR 851462.

- Morton, William Scott; Lewis, Charlton M. (2005), China: Its History and Culture (Fourth ed.), New York City: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-141279-7.

- ISBN 978-0-521-05799-8.

- ——— (1986a), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3; Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, Taipei: Caves Books, ISBN 978-0-521-05801-8.

- ——— (1986b), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology; Part 1, Physics, Taipei: Caves Books, ISBN 978-0-521-05802-5.

- ——— (1986c), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology; Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, Taipei: Caves Books, ISBN 978-0-521-05803-2.

- ——— (1986d), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics, Taipei: Caves Books, ISBN 978-0-521-07060-7.

- Needham, Joseph; ISBN 978-0-521-08690-5.

- Needham, Joseph (1988), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 9, Textile Technology: Spinning and Reeling, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-32021-4.

- Neinhauser, William H.; Hartman, Charles; Ma, Y.W.; ISBN 978-0-253-32983-7.

- Nelson, Howard (1974), "Chinese maps: an exhibition at the British Library", The China Quarterly, 58: 357–362, S2CID 154338508.

- Nishijima, Sadao (1986), "The economic and social history of Former Han", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 545–607, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- Omura, Yoshiaki (2003), Acupuncture Medicine: Its Historical and Clinical Background, Mineola: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-42850-5.

- O'Reilly, Dougald J.W. (2007), Early Civilizations of Southeast Asia, Lanham, New York, Toronto, Plymouth: AltaMira Press, Division of Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, ISBN 978-0-7591-0279-8.

- ISBN 978-0-500-05090-3.

- Pigott, Vincent C. (1999), The Archaeometallurgy of the Asian Old World, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, ISBN 978-0-924171-34-5.

- Psarras, Sophia-Karin (2 February 2015), Han Material Culture: An Archaeological Analysis and Vessel Typology, ISBN 978-1-316-27267-1 – via Google Books

- ISBN 978-0-521-32995-8. (an abridgement of Joseph Needham's work)

- S2CID 251690411.

- Schaefer, Richard T. (2008), Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society: Volume 3, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc, ISBN 978-1-4129-2694-2.

- Shen, Kangshen; ISBN 978-0-19-853936-0.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman (2004), "The Tang architectural icon and the politics of Chinese architectural history", The Art Bulletin, 86 (2): 228–254, JSTOR 3177416.

- ——— (2005a), "Pleasure tower model", in Richard, Naomi Noble (ed.), Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines', New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 275–281, ISBN 978-0-300-10797-5.

- ——— (2005b), "Tower model", in Richard, Naomi Noble (ed.), Recarving China's Past: Art, Archaeology, and Architecture of the 'Wu Family Shrines', New Haven and London: Yale University Press and Princeton University Art Museum, pp. 283–285, ISBN 978-0-300-10797-5.

- Straffin, Philip D. Jr (1998), "Liu Hui and the first Golden Age of Chinese mathematics", Mathematics Magazine, 71 (3): 163–181, JSTOR 2691200.

- Suárez, Thomas (1999), Early Mapping of Southeast Asia, Singapore: Periplus Editions, ISBN 978-962-593-470-9.

- Sun, Xiaochun; Kistemaker, Jacob (1997), The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society, Leiden, New York, Köln: Koninklijke Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-10737-3.

- S2CID 147379141.

- ISBN 978-0-684-83718-5.

- Thorp, Robert L. (1986), "Architectural principles in early Imperial China: structural problems and their solution", The Art Bulletin, 68 (3): 360–378, JSTOR 3050972.

- Tom, K.S. (1989), Echoes from Old China: Life, Legends, and Lore of the Middle Kingdom, Honolulu: The Hawaii Chinese History Center of the University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-1285-0.

- Torday, Laszlo (1997), Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History, Durham: The Durham Academic Press, ISBN 978-1-900838-03-0.

- ISBN 978-1-84176-386-6.

- Wagner, Donald B. (1993), Iron and Steel in Ancient China, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-09632-5.

- ——— (2001), The State and the Iron Industry in Han China, Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Publishing, ISBN 978-87-87062-83-1.

- Wang, Yu-ch'uan (1949), "An outline of The central government of the Former Han dynasty", Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 12 (1/2): 134–187, JSTOR 2718206.

- ISBN 978-0-300-02723-5.

- Wang, Xudang; ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1.

- ISBN 978-0-300-08284-5.

- Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. (2011) [2001], Gender in History: Global Perspectives (2nd ed.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-8995-8

- Xue, Shiqi (2003), "Chinese lexicography past and present", in Hartmann, R.R.K. (ed.), Lexicography: Critical Concepts, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 158–173, ISBN 978-0-415-25365-9.

- Young, Gary K. (2001), Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy, 31 BC – AD 305, London & New York: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-24219-6.

- Yü, Ying-shih (1967), Trade and Expansion in Han China: A Study in the Structure of Sino-Barbarian Economic Relations, Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ——— (1986), "Han foreign relations", in Twitchett, Denis; Loewe, Michael (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 377–462, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.