Hanbali school

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

| Part of a series on Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

The Hanbali school or Hanbalism (

Like the other Sunni schools, it primarily derives

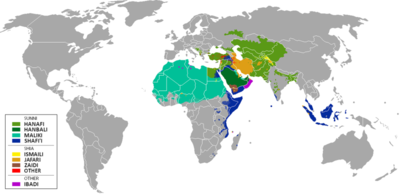

It is found primarily in the countries of

With the rise of the 18th-century conservative

One who ascribes to the Hanbali school is called a Hanbali, Hanbalite or Hanbalist (

History

Like Al-Shafi'i and

Ibn Hanbal never composed an actual systematic legal theory on his own, and was against setting up juristic superstructures. He devoted himself to the task of collection and

Relations with the

According to

At some point between the 10th and 12th centuries, the Hanbali scholars began adopting the term “Salafi". The influential 13th century Hanbali theologian

Now most of the followers of this religion are present in different countries such as Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Oman.[30][31][32]

Principles

Sources of law

Like all other schools of Sunni Islam, the Hanbali school holds that the two primary sources of Islamic law are the

Ibn Hanbal rejected the possibility of religiously binding consensus (Ijma), as it was impossible to verify once later generations of Muslims spread throughout the world,

Ibn Hanbal's strict standards of acceptance regarding the sources of Islamic law were probably due to his suspicion regarding the field of Usul al-Fiqh, which he equated with speculative theology (kalam).[38] While demanding strict application of Qur'an and Hadith, Hanbali Fiqh is nonetheless flexible in areas not covered by Scriptures. In issues where the Qur'an and the Hadiths were ambiguous or vague; the Hanbali Fuqaha (jurists) engaged in Ijtihad to derive rulings. Additionally, the Hanbali madh'hab accepted the Islamic principle of Maslaha ('public interest') in solving the novel issues.[39] In the modern era, Hanbalites have branched out and even delved into matters regarding the upholding (Istislah) of public interest (Maslaha) and even juristic preference (Istihsan), anathema to the earlier Hanbalites as valid methods of determining religious law.

Theology

| Part of a series on Aqidah |

|---|

|

|

Including:

|

Ibn Hanbal taught that the Qur'an is uncreated due to Muslim belief that it is the word of

Distinct rulings

Purity (tahara)

Ablution (wudu')

- Saying "with the name of God" (bi-smi llāh) is necessary, but waived if one forgets or is ignorant.

- It is obligatory and a pillar (rukn) to wash the mouth and nose, and is not waived.

- It is obligatory and a pillar to wipe the entire head, including the ears, and is not waived. Wiping the neck is not recommended.

- It is recommended to lengthen the whiteness that will appear on the Day of Judgement by washing to the top of the arms and shins.

- Impurities, such as blood, pus, and vomit, nullify ablution if they come out the body in large amounts, but not small amounts. If they come out the front or back private parts, it nullifies it regardless of the amount. Also, urine and stool nullify it regardless of the amount and where it came out from.

- Light sleep when standing or sitting does not nullify ablution.

- Touching someone of the opposite sex with any part of the body nullifies ablution if done with lust (shahwah). The hair, teeth, and nails are not included.

- Touching the front or back private part with the hand nullifies ablution. The testicles are not included.

- Wind passing from the woman's front private part nullifies ablution.

- Eating camel meat nullifies ablution, whether raw or cooked. All other parts, such as its fat, liver, or pancreas, do not.

- Washing the dead nullifies ablution.

- Apostasy nullifies ablution.

Impurities (najasa)

- A minimum of three wipes is obligatory to cleanse the impurity after relieving oneself, and any less will not suffice. If there is still impurity after that, more wipes must be used until the effect is achieved. Microscopic amounts are excused.

- Washing the hands three times is obligatory after awakening from a night's sleep. Naps during the day are not included.

- Impurities must be washed seven times with water to be rendered pure. Nothing can cleanse impurities except purifying (ṭahūr) water.

- Transforming one substance into another does not render it pure, even if it changes its chemical properties, except alcohol (khamr).

- If an impurity falls into pure (ṭāhir) water less than two qullahs in volume, all of it is rendered impure (najis). If it is more than two qullahs, it remains pure. If the liquid the impurity falls into is other than water, it will be rendered impure regardless of the amount.

- Semen (madī) is pure.

- Blood, pus, vomit, pre-ejaculate fluid (madhī), and white discharge after urinating (wadī) are impure. However, a small amount of blood and pus is excused.

- Cat hair and saliva are pure.

- All seafood is generally pure and permissible.

- Pigs, dogs, donkeys, predators larger than a cat, birds with talons, and all animals derived from them are all impure and impermissible.

- Leather from unslaughtered animals is impure, even if tanned.

- Rennet from unslaughtered animals is impure and impermissible.

- Vinegar made with human intervention is impure and impermissible, but pure and permissible if formed naturally.

Prayer (salah)

Standing (qiyam)

- It is recommended to grasp (qabd) the hands below the navel, as stated in Kashshaf al-Qina' by Ibrahim an-Nakha'i, and other scholars among the predecessors(salaf).

Other views on where to place them do exist in the school, due to conflicting narrations from Ahmad:

- Above the navel and below the chest[42]

- On the navel

- A choice wherever to place them

- Letting them hang free (ṣadl)

- Grasping them in obligatory prayers, but letting them hang free in voluntary prayers

- Reciting another al-Fatihahis recommended and not obligatory.

- It is recommended to look at the place of prostration when standing and throughout the entire prayer, except the testimony.

Bowing (ruku')

- It is recommended to raise the hands (rafʿ al-yadayn) when going into bowing and rising from it.[42]

- It is obligatory to recite the remembrance, "Glory be to my Lord, the Most Great" (subḥāba rabbiya l-ʿaẓīm), once, and recommended to do so three or more times.

- When standing after bowing, it is obligatory to recite the remembrance, "Our Lord, to you is all praise" (rabbanā laka l-ḥamd). One has a choice whether to grasp the hands like before or not.[43]

Prostration (sujud)

- The fingers should be closed together and facing the direction of prayer(qiblah), including the thumb, and the tips should be align with the top of the shoulders.

- It is obligatory to recite the remembrance, "Glory be to my Lord, the Most High" (subḥāba rabbiya l-aʿlā), once, and recommended to do so three or more times.

Sitting (jalsa)

- It is obligatory to recite the supplication, "Lord, forgive me" (rabbi ghfir lī) once, and recommended to do so three or more times.

Testimony of faith (tashahhud)

- The little and ring fingers of the right hand should be folded in, a circle should be made with the middle finger and thumb, and the index finger should be pointed when saying the name of God (Allāh).[42][44][45]

- It is recommended to look at the finger.

- It is permissible to raise the hands when rising.

- Peace and salutations upon Muhammad and extra supplications are only done in the sitting of the final testimony.

- It is recommended to sit in the outstretched (at-tawarruk) position in the sitting of the final testimony when the prayer has more than one.

Greeting of peace (taslim)

- Two are obligatory and pillars which are not waived. The exact wording must be used: "All peace be on you and the mercy of God" (as-salāmu ʿalaykum wa-raḥmatu llāh). It is not permissible to omit a single letter, not even the definite article al-, or to replace alaykum with alayk.[46]

Voluntary prayers

Odd prayer (salah al-witr)

- It is recommended to pray two cycles (rakʿatayn) consecutively, and then separately. It is recommended to recite the special supplication (qunūt) after bowing, while raising the hands.[46] However, other ways to perform it are permissible.

- After reciting the special supplication, it is recommended to raise the hands when going into prostration.

Congregational prayer

- In the absence of a valid excuse, it is obligatory for adult men to pray in congregation rather than individually.[47]

Other

- Most Hanbali scholars consider admission in a court of law to be indivisible, that is, a plaintiff may not accept some parts of a defendant's testimony while rejecting other parts. This position is also held by the Zahiri school, though opposed by the Hanafi and Maliki schools.[48]

Reception

The Hanbali school is now accepted as the fourth of the mainstream Sunni schools of law. It has traditionally enjoyed a smaller following than the other schools. In the earlier period, Sunni jurisprudence was based on four other schools:

Historically, the school's legitimacy was not always accepted. Muslim exegete

Eventually, the

Differences with other Sunni schools

al-Madina.[citation needed ]

Sanad (transmission chain) is not a widely known figure. In doing so, he was aided by his vast historical knowledge.[citation needed ]

By the end of the classical era, the other three remaining schools had codified their laws into comprehensive jurisprudential systems; enforcing them far and wide. However, the Hanbalis stood apart from the other three madh'habs; by insisting on referring directly back to the Qur’an and Sunnah, to arrive at legal rulings. They also opposed the codification of Sharia (Islamic law) into a comprehensive system of jurisprudence; considering the Qur'an and Hadith to be the paramount sources.[56] Relationship with Sufismheretical innovations in religion; the Hanbali school of Sunni law had a very intimate relationship with Sufism throughout Islamic history.[57]

There is evidence that many early medieval Hanbali scholars were very close to the Sufi martyr and saint Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah.[63] Both these men, sometimes considered to be completely anti-Sufi in their leanings, were actually initiated into the Qadiriyya order of the celebrated mystic and saint Abdul Qadir Gilani,[63] who was himself a renowned Hanbali Faqih. As the Qadiriyya Tariqah is often considered to be the largest and most widespread Sufi order in the world, with many branches spanning from Turkey to Pakistan, one of the largest Sufi branches is effectively founded on Hanbali school.[58] Other prominent Hanbalite scholars who praised Sufism include Ibn 'Aqil, Ibn Qudamah, Ibn Rajab al-Hanbali, Muhammad Ibn ‘Abd al-Wahhab, etc.[64]

Although Muhammad Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab is sometimes regarded as a denier of Sufism, both he and his early disciples acclaimed List of Hanbali scholars

See alsoReferences

Further reading

External links

|