Harry Chauvel

Sir Harry Chauvel | |

|---|---|

Anzac Mounted Division (1916) (1914–15)1st Division (1915–16) New Zealand and Australian Division (1915) 1st Light Horse Brigade | |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | (France) |

The son of a

Promoted to

In 1919, Chauvel was appointed Inspector General, the Army's most senior post. He was forced to maintain an increasingly hollow structure by politicians intent on cutting expenditure. He was concurrently Chief of the General Staff from 1923 until his retirement in 1930. In November 1929, he became the first Australian to be promoted to the rank of general. During the Second World War, he was recalled to duty as Inspector in Chief of the Volunteer Defence Corps.

Early life

Henry George Chauvel was born in

Following a

Chauvel's unit was called up in March 1891 during the

On 9 September 1896, Chauvel transferred to the Queensland Permanent Military Forces with the rank of captain in the

Boer War

In July 1899, the

In the reorganisation that followed, the Queensland Mounted Infantry became part of Major General

On 1 January 1901, the colonies of Australia federated to form the Commonwealth of Australia. When Chauvel returned to Australia on 17 January, he found that during his absence he had become an officer in the newly formed Australian Army. A force of 14,000 troops was assembled for the opening of the first Federal Parliament on 9 May 1901 in Melbourne; Chauvel was selected as brigade major of the mounted contingent, his first Federal posting. He became Staff Officer, Northern Military District, based at Townsville, Queensland, in July. In 1902, Chauvel was appointed to command of the 7th Commonwealth Light Horse, a unit newly raised for service in South Africa,[14] with the local rank of lieutenant colonel.[15] Departing from Brisbane on 17 May 1902, the 7th Commonwealth Light Horse arrived at Durban on 22 June, three weeks after the war ended. It therefore re-embarked for Brisbane, where it was disbanded. Chauvel remained in South Africa for a few weeks in order to tour the battlefields. On returning to Australia he became Staff Officer, Northern Military District once more. He was promoted to the brevet rank of lieutenant colonel in December 1902.[14]

In 1903, Hutton, now

Chauvel knew Keith Jopp of

First World War

War Office

Chauvel was promoted to

Gallipoli

Chauvel began training his brigade upon arrival in Egypt. He was noted for insisting on high standards of dress and bearing from his troops.

Chauvel arrived on 12 May 1915 and took over the critical sector, which included Pope's Hill and Quinn's, Courtney's and Steele's Posts, from Colonel

On 9 July 1915, Chauvel was promoted to

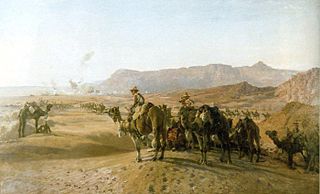

Sinai

Anzac Mounted Division

Chauvel assumed command of the newly formed

Chauvel was no hard-riding gambler against odds. Like Alva, he could on occasion ignore the ardent enthusiasm of his officers and bide his time. Always cool, and looking far enough ahead to see the importance of any particular fight in its proper relation to the war as a whole, he was brave enough to break off an engagement if it promised victory only at what he considered an excessive cost to his men and horses. He fought to win, but not at any price. He sought victory on his own terms. He always retained, even in heated moments of battle, when leaders are often careless of life, a very rare concern for the lives of his men and his horses.

— Henry Gullett official Australian historian[41]

For the

In his report to the War Office on the battle, Murray passed lightly over the part played by the

Desert Column

In October 1916 Major General Sir

Chauvel gained another important success in the

However, Chauvel continued to be concerned about the lack of recognition for Australian and New Zealand troops and on 28 September 1917 wrote:

The point is now that, during the period covered by Sir Archibald's Despatch of 1–3–17, the Australia and New Zealand Troops well know that, with the exception of the 5th Mounted Brigade and some Yeomanry Companies of the I.C.C., they were absolutely the only troops engaged with the enemy on this front and yet they see that they have again got a very small portion indeed of the hundreds of Honours and Rewards (including mentions in Despatches) that have been granted. My Lists when commanding the A. & N.Z. Mounted Division, were modest ones under all the circumstances and in that perhaps I am partly to blame but, as you will see by attached list, a good many of my recommendations were cut out and in some cases those recommended for decorations were not even mentioned in Despatches. I am well aware that it is difficult to do anything now to right this, but consider that the Commander–in–Chief [Allenby] should know that there is a great deal of bitterness over it.

— Chauvel to EEF General Staff[57]

Chauvel appended 32 names of soldiers he recommended for awards that had been ignored. Two New Zealanders recommended for a Bar to their Distinguished Service Orders (DSO) were not even mentioned in despatches and an outstanding Australian regimental commander recommended for the CMG was also not even mentioned in despatches, while a brigade commander and a staff officer Chauvel recommended for DSOs received mentions.[57]

Palestine

In January 1917, a second mounted division – the

In the First Battle of Gaza in March 1917, Chauvel's mission was similar to Rafa and Magdhaba, but on a larger scale. He enveloped the Turkish position at Gaza while the British 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division and 54th (East Anglian) Infantry Division attempted to capture it.[60] When this failed, Chetwode ordered Chauvel to attempt to capture Gaza from the rear. Chauvel successfully improvised a late afternoon assault on Gaza that captured the town despite the barriers of high cactus hedges and fierce enemy opposition, entering it after dark, only to have an out-of-touch Dobell order the mounted troops to withdraw, despite Chauvel's protests. This time his brigadiers at the front, Generals Ryrie and Chaytor, although they believed that Gaza could be held, felt compelled to obey, as they could not see the whole battle. All guns, including captured ones were hauled away, as were all unwounded prisoners, the wounded and even the dead.[61] Chauvel ensured that wounded Turkish prisoners that were unfit to make the march to Deir al-Balah were each left with a full water bottle.[62]

Dobell launched the

Two weeks before Allenby arrived, Chauvel attended an awards ceremony:

Mick Bruxner ... was the first recipient and you should have seen his face when he realised he was going to be kissed ... Irwin of the 1st Regiment is a very tall man and had to have his head pulled down and they ... say that he kissed the old General back. I cannot say as I was having such a job keeping my countenance that I was pretending to read something I had in my hand."

— Chauvel letter to his wife 12 June 1917[68]

Desert Mounted Corps

When Chauvel learned that the Desert Column was to be renamed the 2nd Cavalry Corps he requested

Although some British thought that Allenby should replace Chauvel with a British officer, Allenby retained him in command. However he overrode Chauvel's own preference to appoint a Royal Horse Guards officer, Brigadier General Richard Howard-Vyse, known as "Wombat", as Chauvel's chief of staff. Chauvel thus, on 2 August 1917, became the first Australian to permanently command a corps.[69] A "brass-bound brigadier" was quoted as saying, "Fancy giving the command of the biggest mounted force in the world's history to an Australian."[70] On being told of the appointments, in a letter dated 12 August 1917 Chetwode wrote to congratulate Chauvel, "I cannot say how much I envy you the command of the largest body of mounted men ever under one hand – it is my own trade – but Fate has willed it otherwise."[67][Note 1] At Romani Chauvel had been a battleground commander who led from the front while Chetwode, relying on the phone had been deciding to retreat at the victory at Rafa. Chetwode's "arms length" style of command also impacted the First Battle of Gaza.[71]

In the

Chauvel, however, was still disappointed with the failure to destroy the Turkish army. The Turks had fought hard, forcing the commitment of the Desert Mounted Corps in heavy action before the moment for a sweeping pursuit came. When it did, the men and horses were too tired and could not summon the required energy.

In September 1918, Chauvel was able to effect a secret redeployment of two of his mounted divisions.[82] Allenby launched a surprise attack on the enemy and won the Battle of Megiddo. He then followed up this victory with one of the fastest pursuits in military history – 167 km in only three days.[83] This time he succeeded in destroying the Turkish army. The Desert Mounted Corps moved across the Golan Heights and captured Damascus on 1 October. Between 19 September and 2 October, the Australian Mounted Division lost 21 killed and 71 wounded, and captured 31,335 Turkish prisoners.[84] To restore calm in the city, Chauvel ordered a show of force. Lieutenant Colonel T. E. Lawrence later lampooned this as a "triumphal entry" but it was actually a shrewd political stroke,[85] freeing Chauvel's forces to advance another 300 km to Aleppo, which was captured on 25 October. Five days later, Turkey surrendered.[86] For this victory, Chauvel was again mentioned in despatches.[87]

Chauvel was obliged to remain in the Middle East due to the situation in

Later life

Between the wars

Chauvel's AIF appointment was terminated on 9 December 1919, and the next day he was appointed Inspector General, the Army's most senior post,

In February 1920, Chauvel was promoted to the substantive rank of lieutenant general, back-dated to 31 December 1919. In January 1920, he chaired a committee to examine the future structure of the army. The committee's recommendations proved to be next to impossible to implement in the face of defence cuts that were imposed in 1920 and 1922.[99] On Lieutenant General Brudenell White's retirement as Chief of the General Staff in 1923, that post was divided into two, with Chauvel becoming 1st Chief of the General Staff as well as Inspector General, while Brigadier General Thomas Blamey became 2nd Chief of the General Staff.[100] Chauvel also served as Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee, being the senior of the three service chiefs.[101] In November 1929, he became the first Australian to be promoted to the rank of general.[1] He attempted to maintain the Army's structure in the face of short-sighted politicians intent on cutting expenditure. As a result, the Army became increasingly hollow, retaining the form of a large force without the substance. When conscription was abolished by Prime Minister James Scullin's government in 1929, it was left up to Chauvel to attempt to make the new volunteer system work. He finally retired in April 1930.[102]

Chauvel's sons Ian and Edward resigned their commissions in the Australian Army in 1930 and 1932 respectively, and accepted commissions in cavalry regiments of the

The dedication of the

Second World War and legacy

During the

Chauvel was given a state funeral service at

Portraits of Chauvel are held by the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, the Naval and Military Club in Melbourne, and the Imperial War Museum in London. A portrait by George Washington Lambert is in the possession of the family. Chauvel is commemorated in a bronze plaque in St Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne. His sword is in Christ Church, South Yarra, his uniform in the Australian War Memorial, and his saddle is kept by the 1st Armoured Regiment in South Australia. There is also a memorial window in the chapel of the Royal Military College, Duntroon.[1] Chauvel Street in North Ryde, Sydney is named in his honour.[109]

Chauvel's daughter Elyne Mitchell wrote a number of non-fiction works about her father and his corps. In his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom, T. E. Lawrence provided a wildly inaccurate version of Chauvel.[110] Charles Bean noted that "this wise, good and considerate commander was far from the stupid martinet that readers of Lawrence's Seven Pillars of Wisdom might infer."[111] Lawrence confessed that "little of his book was strict truth though most of it was based on fact."[112]

Chauvel's nephew Charles Chauvel became a well-known film director, whose films included Forty Thousand Horsemen (1940), about the Battle of Beersheba.

Harry Chauvel was portrayed in film: by

See also

- Jean Chauvel (Ambassadeur de France)

Notes

- ^ Murat's Reserve Cavalry in 1805 had been 22,000 while Bessieres' Reserve Cavalry in 1809 had been 29,000, both larger than Chauvel's 20,000. Hill notes the war establishment of a mounted division in July 1917 was 7,991, so Chauvel would have commanded about 24,000. He also notes the reference to "Forty Thousand Horsemen" in the name of a film directed by Charles Chauvel, (Chauvel's nephew) was a myth. [Hill 1978 pp. 119–20, note]

Citations

- ^ ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 3

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 1

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 4–6

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 6–7

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 8–9

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 10–12

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 14–16

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 17–20

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 22–20

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 30

- ^ "No. 27305". The London Gazette. 16 April 1901. p. 2607. mentioned in despatches (Boer War)

- ^ "No. 27306". The London Gazette. 19 April 1901. p. 2699. Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG)

- ^ a b Hill 1978, pp. 30–31

- ^ "No. 27583". The London Gazette. 4 August 1903. p. 4905. Commander, 7th Commonwealth Light Horse

- ^ a b c Hill 1978, pp. 33–37

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 40–42

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 42

- ^ "First World War Service Record – Henry George Chauvel". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 42–46

- ^ Bean 1921, p. 138

- ^ Bean 1921, p. 118

- ^ Bean 1921, p. 216

- ^ Bean 1921, pp. 599–600

- ^ Bean 1924, pp. 116–117

- ^ Bean 1924, pp. 200–201

- ^ Bean 1924, pp. 248–253

- ^ Bean 1924, pp. 206–229

- ^ "No. 29354". The London Gazette (Supplement). 5 November 1915. p. 11001. mentioned in despatches (Quinn's Post)

- ^ "No. 29224". The London Gazette. 9 July 1915. p. 6707. appointment to Brigadier General

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 58

- ^ "No. 29455". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 January 1916. p. 1207. mentioned in despatches (August offensive)

- ^ Bean 1929, p. 44

- ^ "No. 29664". The London Gazette (Supplement). 13 July 1916. p. 6942. mentioned in despatches (Gallipoli evacuation)

- ^ "No. 29438". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 January 1916. p. 564. Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB)

- ^ Gullett 1923, p. 58

- ^ Gullett 1923, p. 68

- ^ "No. 29763". The London Gazette (Supplement). 25 September 1916. p. 9341. mentioned in despatches (defence of Suez Canal)

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 70–71

- ^ a b Hill 1978, pp. 82–83

- ^ Gullett 1923, p. 63

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 74–77

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 167–169

- ^ Gullett 1923, p. 173

- ^ Gullett 1923, p. 191

- ^ Gullett 1923, p. 184

- ^ Gullett 1923, p. 192

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 94

- ^ "No. 29845". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 December 1916. p. 11807. mentioned in despatches (Battle of Romani)

- ^ Gullett 1923, p. 207

- ^ MacMunn & Falls 1928, p. 203

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 214–228

- ^ Gullett 1923, p. 228

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 90–93

- ^ "No. 29909". The London Gazette. 18 January 1917. p. 749. Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG)

- ^ "No. 30169". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 July 1917. p. 6772. mentioned in despatches (Battle of Magdhaba)

- ^ a b Hill 1978, p. 122

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 255–257

- ^ Falls & MacMunn 1930, pp. 273–4

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 264–265

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 277–286

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 105

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 302–307

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 334–335

- ^ a b Gullett 1923, pp. 361–365

- ^ Cutlack 1941, pp. 63–4

- ^ a b c Hill 1978, p. 118

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 116

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 118–123

- ^ Paterson 1934, p. 120

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 119–20

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 345–351

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 363–367

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 394–402

- ^ "No. 30480". The London Gazette (Supplement). 15 January 1918. p. 937. mentioned in despatches (Beersheba)

- ^ "No. 30492". The London Gazette (Supplement). 25 January 1918. p. 1195. mentioned in despatches (Beersheba)

- ^ "No. 30624". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 April 1918. p. 4409. Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB)

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 439–444

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 651–657

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 142–145

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 639–641

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 688–692

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 693–712

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 761–772

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 181–182

- ^ Gullett 1923, pp. 776–779

- ^ "No. 31138". The London Gazette. 21 January 1919. p. 1164. mentioned in despatches (Damascus and Aleppo)

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 190–196

- ^ "No. 31395". The London Gazette. 9 June 1919. p. 7422. Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG)

- ^ "No. 31393". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 June 1919. p. 7398. Croix de Guerre avec Palme

- ^ "No. 31002". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 November 1918. p. 13273. Order of the Nile

- ^ "No. 31498". The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 August 1919. p. 10194. mentioned in despatches (commander of the Desert Mounted Corps)

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 196

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 199

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 218

- ^ Wood 2006, pp. 57–58

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 214

- ^ Long 1952, p. 5

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 200–203

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 207–209

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 215

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 217–219

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 222–223

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 223

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 225–226

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 222

- ^ Hill 1978, pp. 228–229

- The Argus, p. 3, 6 March 1945

- ^ "Origins of the Street Names of the City of Ryde" (PDF). The Ryde District Historical Society. 7 October 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 224

- ^ Bean 1948, p. 321

- ^ Hill 1978, p. 181

References

- OCLC 52501250

- —— (1924), Volume II – The Story of ANZAC from 4 May 1915, to the Evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula, OCLC 458675365

- —— (1929), Volume III – The Australian Imperial Force in France 1916, OCLC 7978099

- —— (1948), Gallipoli Mission, Canberra: Australian War Memorial, OCLC 23255870

- Cutlack, Frederic Morley (1941), The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War, 1914–1918, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, vol. VIII (11th ed.), Canberra: Australian War Memorial, OCLC 220900299

- Falls, Cyril; MacMunn, George (1930), Military Operations Egypt & Palestine from the Outbreak of War With Germany to June 1917, Official History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence, vol. 1, London: HM Stationery Office, OCLC 610273484

- OCLC 463492101

- OCLC 5003626

- OCLC 3134176

- MacMunn, George; OCLC 152077308

- OCLC 223273391

- Wood, James (2006), Chiefs of the Australian Army: Higher Command of the Australian Military Forces 1901–1914, Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military History Publications, OCLC 225200296

External links

- His introduction to The New Zealanders in Sinai and Palestine

- Chauvel at www.aif.adfa.edu.au

- "Boer War and First World War Service Record – Henry George Chauvel". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- Monument Australia – plaque at St Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne

- Virtual War Memorial Australia