Worship of heavenly bodies

The worship of heavenly bodies is the veneration of

The most notable instances of this are

The related term astrolatry usually implies polytheism. Some Abrahamic religions prohibit astrolatry as idolatrous. Pole star worship was also banned by imperial decree in Heian period Japan.

Etymology

Astrolatry has the suffix -λάτρης, itself related to λάτρις latris, "worshipper" or λατρεύειν latreuein, "to worship" from λάτρον latron, "payment".

Ancient and medieval Near East

Mesopotamia

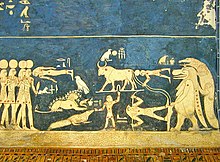

Babylonian astronomy from early times associates stars with deities, but the identification of the heavens as the residence of an anthropomorphic pantheon, and later of monotheistic God and his retinue of angels, is a later development, gradually replacing the notion of the pantheon residing or convening on the summit of high mountains. Archibald Sayce (1913) argues for a parallelism of the "stellar theology" of Babylon and Egypt, both countries absorbing popular star-worship into the official pantheon of their respective state religions by identification of gods with stars or planets.[1]

The Chaldeans, who came to be seen as the prototypical astrologers and star-worshippers by the Greeks, migrated into Mesopotamia c. 940–860 BCE.[2] Astral religion does not appear to have been common in the Levant prior to the Iron Age, but becomes popular under Assyrian influence around the 7th-century BCE.[3] The Chaldeans gained ascendancy, ruling Babylonia from 608 to 557 BCE.[4] The Hebrew Bible was substantially composed during this period (roughly corresponding to the period of the Babylonian captivity).

Egypt

Astral cults were probably an early feature of religion in

One of the most notable examples of astral worship in ancient Egypt is the goddess Sopdet, identified with the star Sirius.[8] Sopdet's rising coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile, a crucial event that sustained Egyptian agriculture. The goddess was venerated as a harbinger of the inundation, marking the beginning of a new agricultural cycle and symbolizing fertility and renewal. This connection between Sopdet and the Nile flood underscores the profound link between celestial phenomena and earthly prosperity in ancient Egyptian culture. She was known to the Greeks as Sothis.

Sopdet is the consort of

Sabians

Among the various religious groups which in the 9th and 10th centuries CE came to be identified with the mysterious Sabians mentioned in the Quran (sometimes also spelled 'Sabaeans' or 'Sabeans', but not to be confused with the Sabaeans of South Arabia),[15] at least two groups appear to have engaged in some kind of star worship.

By far the most famous of these two are the

Apart from the Sabians of Harran, there were also various religious groups living in the

Asia

China

Heaven worship is a

Heaven worship is closely linked with ancestor veneration and polytheism, as the ancestors and the gods are seen as a medium between Heaven and man. The Emperor of China, also known as the "Son of Heaven", derived the Mandate of Heaven, and thus his legitimacy as ruler, from his supposed ability to commune with Heaven on behalf of his nation.[29][30]

Star worship was widespread in Asia, especially in Mongolia

The Sanxing (Chinese: 三星; lit. 'Three Stars') are the gods of the three stars or constellations considered essential in Chinese astrology and mythology: Jupiter, Ursa Major, and Sirius. Fu, Lu, and Shou (traditional Chinese: 福祿壽; simplified Chinese: 福禄寿; pinyin: Fú Lù Shòu; Cantonese Yale: Fūk Luhk Sauh), or Cai, Zi and Shou (財子壽) are also the embodiments of Fortune (Fu), presiding over planet Jupiter, Prosperity (Lu), presiding over Ursa Major, and Longevity (Shou), presiding over Sirius.[37]

During the Tang dynasty, Chinese Buddhism adopted Taoist Big Dipper worship, borrowing various texts and rituals which were then modified to conform with Buddhist practices and doctrines. The cult of the Big Dipper was eventually absorbed into the cults of various Buddhist divinities, Myōken being one of these.[38]

Japan

Star worship was also practiced in Japan.[39][40][41] Japanese star worship is largely based on Chinese cosmology.[42] According to Bernard Faure, "the cosmotheistic nature of esoteric Buddhism provided an easy bridge for cultural translation between Indian and Chinese cosmologies, on the one hand, and between Indian astrology and local Japanese folk beliefs about the stars, on the other".[42]

Originally an 11th-century Buddhist temple dedicated to Myōken, converted into a Shinto shrine during the Meiji period.

The cult of Myōken is thought to have been brought into Japan during the 7th century by immigrants (toraijin) from Goguryeo and Baekje. During the reign of Emperor Tenji (661–672), the toraijin were resettled in the easternmost parts of the country; as a result, Myōken worship spread throughout the eastern provinces.[43]

By the Heian period, pole star worship had become widespread enough that imperial decrees banned it for the reason that it involved "mingling of men and women", and thus caused ritual impurity. Pole star worship was also forbidden among the inhabitants of the capital and nearby areas when the imperial princess (Saiō) made her way to Ise to begin her service at the shrines. Nevertheless, the cult of the pole star left its mark on imperial rituals such as the emperor's enthronement and the worship of the imperial clan deity at Ise Shrine.[44] Worship of the pole star was also practiced in Onmyōdō, where it was deified as Chintaku Reifujin (鎮宅霊符神).[45]

Myōken worship was particularly prevalent among clans based in eastern Japan (the modern

The Americas

Celestial objects hold a significant place within

Heavenly bodies held spiritual wisdom. The

Indigenous American cultures encapsulate a holistic worldview that acknowledges the interplay of humanity, nature, and the cosmos. Oral traditions transmitted cosmic stories, infusing mythologies, songs, and ceremonies with cosmic significance.[52] These narratives emphasized the belief that the celestial realm offered insights into origins and purpose.[49]

Judaism

The Hebrew Bible contains repeated reference to astrolatry. Deuteronomy 4:19, 17:3 contains a stern warning against worshipping the Sun, Moon, stars or any of the heavenly host. Relapse into worshipping the host of heaven, i.e. the stars, is said to have been the cause of the fall of the kingdom of Judah in II Kings 17:16. King Josiah in 621 BCE is recorded as having abolished all kinds of idolatry in Judah, but astrolatry was continued in private (Zeph. 1:5; Jer. 8:2, 19:13). Ezekiel (8:16) describes sun-worship practised in the court of the temple of Jerusalem, and Jeremiah (44:17) says that even after the destruction of the temple, women in particular insisted on continuing their worship of the "Queen of Heaven".[58]

Christianity

Crucifixion darkness is an episode described in three of the canonical gospels in which the sky becomes dark during the day, during the crucifixion of Jesus as a sign of his divinity.[59][60][61]

Augustine of Hippo criticized sun- and star-worship in De Vera Religione (37.68) and De civitate Dei (5.1–8). Pope Leo the Great also denounced astrolatry and the cult of Sol Invictus, which he contrasted with the Christian nativity.[citation needed]

Islam

Astrolatry is mentioned in the

Muhammad's teachings, as documented in Hadith literature, reflect his commitment to monotheism and opposition to idolatry.[66] Academic studies in Islamic theology and comparative religion affirm the contrast between Islamic monotheism and the practice of astrolatry.[67] Islamic scholars and researchers underline that the focus of Islamic spirituality remains centered on the worship of God alone, with no association of divinity to any created entities, including celestial bodies.[68]

Thelema

| Part of a series on |

| Thelema |

|---|

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2024) |

See also

- Archeoastronomy

- Astraea

- Astraeus

- Astronomy and religion

- Astrological age

- Astrotheology

- Babylonian astrology

- Behenian fixed star

- Body of light

- Ceremonial magic

- Decan

- Eosphorus

- Hellenistic astrology

- History of astrology

- History of astronomy

- Lunar station

- Magic and religion

- Natural theology

- Nature worship

- Pantheon

- Planets in astrology

- Pleiades in folklore and literature

- Religious cosmology

- Renaissance magic

- Royal stars

- Seven Heavens

- Sidereal compass rose

- Stars in astrology

- Sky father

- Star people

- Stellar deities

- Venusian deities

Notes

- ^ On the Sabians of Harran, see further Dozy & de Goeje (1884); Margoliouth (1913); Tardieu (1986); Tardieu (1987); Peters (1990); Green (1992); Fahd (1960–2007); Strohmaier (1996); Genequand (1999); Elukin (2002); Stroumsa (2004); De Smet (2010).

References

Citations

- ^ Sayce (1913), pp. 237ff.

- ^ Oppenheim & Reiner (1977).

- ^ Cooley (2011), p. 287.

- ^ Beaulieu (2018), pp. 4, 12, 178.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 12.

- ^ Wilkinson 2003, p. 90.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2003, p. 91.

- ^ Redford (2001).

- ^ Hill (2016).

- ^ a b Wilkinson (2003), p. 167.

- ^ Wilkinson (2003), p. 211.

- ^ Wilkinson (2003), p. 127.

- ^ Wilkinson (2003), p. 168.

- ^ Ritner (1993).

- ^ On the Sabians generally, see De Blois (1960–2007); De Blois (2004); Fahd (1960–2007); Van Bladel (2009).

- ^ De Blois (1960–2007).

- ^ Van Bladel (2009), p. 68; cf. p. 70.

- ^ Van Bladel (2009), p. 65. A genealogical table of Thabit ibn Qurra's family is given by De Blois (1960–2007). On some of his descendants, see Roberts (2017).

- ^ Hjärpe (1972) (as cited by Van Bladel (2009), pp. 68–69).

- ^ Van Bladel (2009), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Van Bladel (2009), p. 70.

- ^ Van Bladel (2017), pp. 14, 71. On the Mesopotamian Marshes in the early Islamic period, see pp. 60–69.

- Elchasaites, whom other scholars see as Mandaeans.

- ^ Van Bladel (2017), pp. 71–72.

- ^ Translation by Van Bladel (2017), p. 71.

- ^ Hämeen-Anttila (2006), pp. 46–52.

- ^ Lü & Gong (2014), p. 71.

- ^ Yao & Zhao (2010), p. 155.

- ^ Fung (2008), p. 163.

- ^ Lü & Gong (2014), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Heissig (1980), pp. 82–4.

- ^ Yu & Lancaster (1989), p. 58.

- ^ Schafer (1977), p. 221.

- ^ Gillman (2010), p. 108.

- ^ Master of Silent Whistle Studio (2020), p. 211, n.16.

- ^ Liu Kwang-ching, “Socioethics as Orthodoxy,” in Liu Kwang-ching, ed., Orthodoxy In Late Imperial China (Berkeley, 1990), 53-100:60.

- ^ (in Chinese) 福禄寿星 Archived 2006-07-22 at the Wayback Machine. British Taoist Association.

- ^ Orzech, Sørensen & Payne (2011), pp. 238–239.

- ^ Bocking (2006).

- ^ Goto (2020).

- ^ Rambelli & Teeuwen (2003).

- ^ a b Faure (2015), p. 52.

- ^ "妙見菩薩と妙見信仰". 梅松山円泉寺. Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ Rambelli & Teeuwen (2003), pp. 35–36, 164–167.

- ^ Friday (2017), p. 340.

- ^ "千葉神社". 本地垂迹資料便覧 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ "千葉氏と北辰(妙見)信仰". Chiba City Official Website (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ "妙見菩薩「開運大野妙見大菩薩」". 日蓮宗 法華道場 光胤山 本光寺 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- ^ a b c Bucko (1998).

- ^ Valencius (2013).

- ^ a b Jones (2015).

- ^ a b Spence (1990).

- ^ Means (2016).

- ^ Goodman (2017).

- ^ Lockett (2018).

- ^ La Vere (1998), p. 7.

- ^ Cobo (1990), pp. 25–31.

- ^ Seligsohn (1906).

- ^ Matthew 27:45

- ^ Mark 15:33

- ^ Luke 23:44

- ^ Rosenberg 1972.

- ^ Brown (2015).

- ^ Qur'an 112:1-4.

- ^ Esack (2002).

- ^ Turner (2006).

- ^ Nasr (2003).

- ^ Smith (1998).

- ^ Crowley (2004).

- ^ Crowley (1991).

Works cited

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2018). A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1405188999.

- Bocking, B. (2006). Dolce, Lucia (ed.). "The Worship of Stars in Japanese Religious Practice". Special Double Issue of Culture and Cosmos: A Journal of the History of Astrology and Cultural Astronomy. 10 (1–2). Bristol: Culture and Cosmos. ISSN 1368-6534.

- Brown, Jonathan A. C. (2015). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications.

- Bucko, Raymond A. (1998). The Lakota Ritual of the Sweat Lodge: History and Contemporary Practice. University of Nebraska Press.

- Cobo, Father Berrnabe (1990). Hamilton, Roland (ed.). Inca Religion and Customs. Translated by Roland Hamilton. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292738546.

- Cooley, J. L. (2011). "Astral Religion in Ugarit and Ancient Israel". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 70 (2): 281–287. S2CID 164128277.

- ISBN 1-56184-028-9.

- Crowley, Aleister (2004). The Book of the Law: Liber Al Vel Legis. Red Wheel Weiser. ISBN 978-1578633081.

- De Blois, François (1960–2007). "Ṣābiʾ". In .

- De Blois, François (2004). "Sabians". In .

- De Smet, Daniel (2010). "Le Platon arabe et les Sabéens de Ḥarrān. La 'voie diffuse' de la transmission du platonisme en terre d'Islam". Res Antiquae. 7: 73–86. ISBN 978-2-87457-034-6.

- OCLC 935749094.

- Elukin, Jonathan (2002). "Maimonides and the Rise and Fall of the Sabians: Explaining Mosaic Laws and the Limits of Scholarship". Journal of the History of Ideas. 63 (4): 619–637. JSTOR 3654163.

- Esack, Farid (2002). The Qur'an: A Short Introduction. Oneworld Publications.

- Fahd, Toufic (1960–2007). "Ṣābiʾa". In .

- Faure, B. (2015). The Fluid Pantheon: Gods of Medieval Japan. Vol. 1. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824857028.

- ISBN 9781351692021.

- Fung, Yiu-ming (2008). "Problematizing Contemporary Confucianism in East Asia". In Richey, Jeffrey (ed.). Teaching Confucianism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198042563.

- Genequand, Charles (1999). "Idolâtrie, astrolâtrie, et sabéisme". Studia Islamica. 89 (89): 109–128. JSTOR 1596088.

- Gillman, D. (2010). The Idea of Cultural Heritage. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521192552.

- Goodman, R. (2017). Lakota Star Knowledge: Studies in Lakota Stellar Theology. SGU Publishing. ISBN 978-0998950501.

- Goto, Akira (2020). Cultural Astronomy of the Japanese Archipelago: Exploring the Japanese Skyscape. United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-0367407988.

- Green, Tamara M. (1992). The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran. Religions in the Graeco-Roman World. Vol. 114. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09513-7.

- ISBN 978-90-04-15010-2.

- Heissig, Walther (1980). The Religions of Mongolia. Translated by Geoffrey Samuel. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520038578.

- Hill, J. (2016). "Sopdet". Ancient Egypt Online. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Hjärpe, Jan (1972). Analyse critique des traditions arabes sur les Sabéens harraniens (PhD diss.). University of Uppsala.

- Jones, David M. (2015). The Inca World: Ancient People & Places. Thames & Hudson.

- La Vere, D. (1998). Life Among the Texas Indians: The WPA Narratives. College Station: Texas A & M University Press. ISBN 978-1603445528.

- Lockett, Chynna (October 3, 2018). "Lakota Star Knowledge-Milky Way Spirit Path". SDPB Radio. South Dallas Public Broadcasting. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Lü, Daji; Gong, Xuezeng (2014). Marxism and Religion. Religious Studies in Contemporary China. Brill. ISBN 978-9047428022.

- OCLC 4993011.

- Master of Silent Whistle Studio (2020). Further Adventures on the Journey to the West. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295747736.

- Means, Binesikwe (September 12, 2016). "For Lakota, Traditional Astronomy is Key to Their Culture's Past and Future". Global Press Journal. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (2003). Islam: Religion, History, and Civilization. HarperOne.

- Oppenheim, A. L.; Reiner, E. (1977). Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226631875.

- Orzech, Charles; Sørensen, Henrik; Payne, Richard, eds. (2011). Esoteric Buddhism and the Tantras in East Asia. Brill. ISBN 978-9004184916.

- ISBN 9780874803426.

- Rambelli, Fabio; Teeuwen, Mark, eds. (2003). Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0415297479.

- Redford, Donald B. (2001). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

- Ritner, Robert K. (1993). The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization. Vol. 54.

- Roberts, Alexandre M. (2017). "Being a Sabian at Court in Tenth-Century Baghdad". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 137 (2): 253–277. doi:10.17613/M6GB8Z.

- Rosenberg, R. A. (1972). "The 'Star of the Messiah' Reconsidered". Biblica. 53 (1): 105–109. JSTOR 42609680.

- Sayce, Archibald Henry (1913). The Religion of Ancient Egypt. Adamant Media Corporation.

- Schafer, E. H. (1977). Pacing the Void : Tʻang Approaches to the Stars. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520033443.

- Seligsohn, M. (1906). "Star-worship". Jewish Encyclopedia– via jewishencyclopedia.com.

- Smith, Jane I. (1998). The World Religions. Cambridge University Press.

- Spence, Lewis (1990). The Myths of Mexico and Peru. Dover Publications.

- OCLC 643711267.

- Reprinted in Strohmaier, Gotthard (2003). Hellas im Islam: Interdisziplinäre Studien zur Ikonographie, Wissenschaft und Religionsgeschichte. Diskurse der Arabistik. Vol. 6. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 167–169. ISBN 978-3-447-04637-4.

- Reprinted in Strohmaier, Gotthard (2003). Hellas im Islam: Interdisziplinäre Studien zur Ikonographie, Wissenschaft und Religionsgeschichte. Diskurse der Arabistik. Vol. 6. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 167–169.

- ISBN 9789042914582.

- .

- ISBN 9783110109245.

- Turner, Colin (2006). Islam: The Basics. Routledge.

- Valencius, Conevery (2013). The Lost History of the New Madrid Earthquakes. University of Chicago Press.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2009). "Hermes and the Ṣābians of Ḥarrān". The Arabic Hermes: From Pagan Sage to Prophet of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 64–118. ISBN 978-0-19-537613-5.

- Van Bladel, Kevin (2017). From Sasanian Mandaeans to Ṣābians of the Marshes. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-33943-9.

- ISBN 0-500-05120-8.

- ISBN 9781847064752.

- Yu, Chai-Shin; Lancaster, Lewis R., eds. (1989). Introduction of Buddhism to Korea: New Cultural Patterns. South Korea: Asian Humanities Press. ISBN 978-0895818881.

Further reading

- Aakhus, P. (2008). "Astral Magic in the Renaissance: Gems, Poetry, and Patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici". Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft. 3 (2): 185–206. S2CID 161829239.

- Albertz, R.; Schmitt, R (2012). Family and Household Religion in Ancient Israel and the Levant. United States: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-1575062327.

- Al-Ghazali, Muhammad (2007). Ihya' Ulum al-Din [Revival of the Religious Sciences]. Dar al-Kotob al-Ilmiyah.

- Ananthaswamy, Anil (14 August 2013). "World's oldest temple built to worship the dog star". New Scientist. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Bender, Herman E. (2017). "The Star Beings and stones: Petroforms and the reflection of Native American cosmology, myth and stellar traditions". Journal of Lithic Studies. 4 (4): 77–116. . Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Casey, Maurice (2014). Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths?. T&T Clark.

- Crowhurst, D. (2021). Stellas Daemonum: The Orders of the Daemons. Red Wheel/Weiser. ISBN 978-1578636914.

- Hill, J. H. (2009) [1895]. Astral Worship. United States: Arc Manor. ISBN 978-1604507119.

- Kim, S. (2019). Shinra Myōjin and Buddhist Networks of the East Asian "Mediterranean". University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824877996.

- McCluskey, S. C. (2000). Astronomies and Cultures in Early Medieval Europe. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521778527.

- Mortimer, J. R. (1896). "Ancient British Star-worship indicated by the Grouping of Barrows". Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological and Polytechnic Society. 13 (2): 201–209. . Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- Pedersen, Hillary Eve (2010). The Five Great Space Repository Bodhisattvas: Lineage, Protection and Celestial Authority in Ninth-Century Japan (PDF) (PhD Thesis). University of Kansas. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- Peters, Ted (2014). "Astrotheology: A Constructive Proposal". Zygon: Journal of Religion & Science. 49 (2): 443–57. .

- S2CID 170507750.

- Reiner, Erica (1995). "Astral Magic in Babylonia". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 85 (4): i-150. JSTOR 1006642.

- Rohrbacher, Peter (2019). "Encrypted Astronomy: Astral Mythologies and Ancient Mexican Studies in Austria, 1910–1945". Revista de Antropologia. 62 (1). Universidade de São Paulo: 140–161. S2CID 151040522.

- Rumor, Maddalena (2020). "Babylonian Astro-Medicine, Quadruplicities and Pliny the Elder". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie & Vorderasiatische Archäologie. 111 (1): 47–76. S2CID 235779490.

- Schaafsma, P. (2015). "The Darts of Dawn: The Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli Venus Complex in the Iconography of Mesoamerica and the American Southwest". Journal of the Southwest. 57 (1): 1–102. S2CID 109601941. Retrieved 2021-12-06.

- Selin, Helaine (2014). Astronomy Across Cultures. Springer My Copy UK. ISBN 978-9401141802.

- Spence, Lewis (1917). "Chapter VIII - Babylonian Star-worship". Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria. Retrieved 2021-12-04 – via wisdomlib.org.

- Springett, B. H. (2016). Secret Sects of Syria. United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 978-1138981546.

- Tanzella-Nitti, Giuseppe (2002). "Sky". Interdisciplinary Encyclopedia of Religion and Science. ISSN 2037-2329.

- Ten Grotenhuis, E. (1998). Japanese Mandalas: Representations of Sacred Geography. University of Hawaii Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0824863111. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- Thompson, Cath (2017). A Handbook of Stellar Magick. West Yorkshire: Hadean Press. ISBN 978-1907881718.

- VanPool, Christine S.; VanPool, Todd L.; Phillips, David A. (Jr.), eds. (2006). Religion in the Prehispanic Southwest. AltaMira Press.

- Walker, Theodore; Wickramasinghe, Chandra (2015). The Big Bang and God: An Astro-Theology. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-1-349-57419-3.

- Wheeler, Brannon M.; Walker, Joel Thomas; Noegel, Scott B., eds. (2003). Prayer, Magic, and the Stars in the Ancient and Late Antique World. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271022574.

- Wrogemann, H. (2019). Intercultural Theology, Volume Three: A Theology of Interreligious Relations. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0830850990.

External links

- The Development, Heyday, and Demise of Panbabylonism by Gary D. Thompson

- Native American Star Lore Dakota and Lakota

- The Star Mandala Archived 2021-12-04 at the Wayback Machine at Kyoto National Museum

- Star Worship in Japan, 28 Constellations (Lunar Mansions, Moon Stations), Pole Star, Big Dipper, Planets, Nine Luminaries