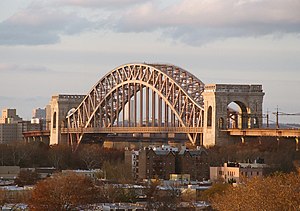

Hell Gate Bridge

Hell Gate Bridge | |

|---|---|

12.5 kV 60 Hz AC catenary (Northeast Corridor only) | |

| History | |

| Architect | Henry Hornbostel |

| Designer | Gustav Lindenthal |

| Constructed by | American Bridge Inc. |

| Fabrication by | American Bridge Company |

| Construction start | 1912 |

| Construction end | 1916 |

| Opened | March 9, 1917[1] |

| Location | |

| |

The Hell Gate Bridge (originally the New York Connecting Railroad Bridge) is a railroad bridge in New York City, New York, United States. The bridge carries two tracks of Amtrak's Northeast Corridor and one freight track between Astoria, Queens, to Port Morris, Bronx, via Randalls and Wards Islands. Its main span is a 1,017-foot (310 m) steel through arch across Hell Gate, a strait of the East River that separates Wards Island from Queens. The bridge also includes several approach viaducts and two spans across smaller waterways. Including approaches, the bridge is 17,000 feet (5,200 m) long. It is one of the few rail connections from Long Island, of which Queens is part, to the rest of the United States.[a]

The New York Connecting Railroad (NYCR) was formed in 1892 to build the bridge, linking New York and the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) with New England and the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad (NH). A cantilever bridge across Hell Gate was proposed in 1900, but the plan was changed to a through-arch bridge after repeated delays. Construction was overseen by the engineers Gustav Lindenthal, Othmar Ammann, and David B. Steinman and architect Henry Hornbostel. The bridge was dedicated on March 9, 1917, and was the world's longest steel arch bridge until the Bayonne Bridge opened in 1931. Various proposals to modify the bridge in the 1920s were unsuccessful. The bridge was renovated in the 1990s following three decades of deterioration.

The main span is a

Development

Planning

At the end of the 19th century, there was no direct rail connection between

1890s progress

The

By the beginning of 1899, the NYCR had received estimates for a bridge connecting Port Morris in the Bronx, Randalls Island, Wards Islands, and Astoria in Long Island.[12] The 800-foot-long (240 m), 150-foot-high (46 m) bridge was to connect the New York Central Railroad and NH lines in the Bronx with the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) and South Brooklyn Railway lines on Long Island.[12][13] A state senator introduced a bill in February 1899 to incorporate the Wards Island Bridge Company to construct the bridge.[8] The following month, the NYCR's directors held a meeting with New York Central's directors about the construction of the line.[13] The New York Central expressed interest in the planned Hell Gate Bridge, as the railroad intended to use it for both passenger and freight traffic.[14]

Cantilever plan

The New York State Legislature passed a bill in April 1900, authorizing the NYCR to build a bridge from the Port Morris station in the Bronx to the

By October 1900, grading of land for the bridge and its approach viaducts had commenced, and public hearings about the bridge were being hosted.

Work on the belt line was about to begin by early 1902,

Arch plan

The PRR hired New York City bridge commissioner Gustav Lindenthal as its consulting structural engineer in 1904.[2][18] To avoid hospitals on Wards Island, the viaduct needed to curve north immediately upon reaching Wards Island;[41] this ruled out the original cantilever design, which required a straight "anchor span".[42][43] Instead, Lindenthal first considered a continuous truss bridge, a suspension bridge, and a cantilever bridge across Hell Gate.[18][44] After rejecting all three designs, Lindenthal studied designs for a spandrel arch and a cantilever arch,[18][45] both of which would be cheaper than either the suspension or cantilever proposals.[41] The crescent-arch design would be thicker at its crown than at either end, while the spandrel-arch design would be thicker at its ends than at the crown.[45][46] Although the crescent-arch design required less steel, Lindenthal liked the design of the spandrel arch because it appeared sturdier and because it complemented his designs for masonry towers at either end.[46] Ultimately, he chose a modified form of the spandrel-arch design.[2][47] His assistant Othmar Ammann wrote that the arch design would allow the bridge to serve as a figurative portal to the Port of New York and New Jersey.[48]

In early 1905, the PRR sent engineers and workers to make borings for the bridge's foundation in Astoria.[49] Work on the bridge's superstructure was delayed because the New York City Board of Aldermen would not approve several aspects of the franchise,[50] prompting an unsuccessful proposal to remove the aldermen's ability to grant franchises.[51] Among other things, the aldermen wanted the bridge to use electric power exclusively, provide space for vehicles and pedestrians, and allow the city to add utility wires to the bridge.[52] New York Governor Frank W. Higgins signed a bill in mid-1905, allowing the start of construction to be postponed by several months.[53] That November, the NYCR asked the Rapid Transit Commission to renew its application for a franchise, citing delays from the Board of Aldermen. The negotiations over the franchise sometimes turned contentious,[54] but the PRR ultimately was promised a franchise from the city in December 1906.[55] By then, the bridge was planned to fit four tracks, though only two would be used initially.[56] The original two-track plan had been changed after the architects found that the cost of converting a two-track bridge to four tracks would be much higher than the upfront cost of a four-track bridge.[57]

The New York City Board of Estimate approved the NYCR's franchise in February 1907.[58] Rea submitted plans for the arch bridge in May 1907 to the city's Municipal Art Commission.[59] The arch would have a clear span of 1,000 feet (300 m), the longest of its kind in the world, and would carry two passenger tracks and two freight tracks. The remainder of the bridge would be a viaduct made of reinforced concrete and steel plate girders.[59][60] The plans were drawn up by consulting engineer Gustav Lindenthal and architects Palmer and Hornbostel.[60][61] That June, the Rapid Transit Commission voted to amend the NYCR's franchise.[62] The franchise allowed the NYCR to construct a viaduct across Wards Island, placing the railroad in possible conflict with the New York State Hospital Commission, which had leased the island from the city,[63] although the hospital commission ultimately did allow engineers to survey the island.[64] The Municipal Art Commission rejected the original bridge plans in July 1907 as "not artistic".[65]

Land acquisition and finalization of plans

During the late 1900s, the NH and PRR acquired land for the bridge's right-of-way.[66] The first house in the bridge's right-of-way was relocated at the beginning of 1908.[67] The Pennsylvania Railroad announced in December 1908 that, as soon as Pennsylvania Station in Manhattan was completed, the railroad would begin constructing the bridge.[68][69] The bridge was to cost up to $20 million.[69] By early 1909, the NH had acquired all of the necessary land for the Bronx approach, while the PRR was still acquiring land in Queens for both the passenger and freight lines.[66] The PRR agreed to buy the last piece of land for the Queens approach that July,[70] at which point the cost of the bridge had increased to $25 million.[71] The NYCR's engineers prepared new plans for the main span's piers the same year.[72] That December, the PRR and NH agreed to share the cost of the bridge's construction.[73] The Hell Gate Bridge was to be the fifth bridge across the East River (after the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro bridges), as well as the first built by a private company rather than the city government.[74]

By early 1910, the plans for the arch's piers were being revised,[75] and surveyors were studying the route of the bridge and its approaches.[76] The plans for the steelwork were revised the same year to accommodate a heavier type of trackbed.[77] The PRR, NH, and LIRR were concurrently finalizing contracts for the construction of the NYCR line, which had commenced in mid-1910.[78] The revised plans for the main span were not submitted to the Municipal Art Commission until early 1911,[79] and a contract for the bridge's steel had still not been awarded.[80] The PRR took title to the last remaining land lots in Queens in June 1911.[81] By the end of the year, the designs for the Bronx Kill and Little Hell Gate spans were still being revised,[82] and land condemnation for the bridge was nearly finished.[83] Lindenthal estimated in late 1911 that the bridge would cost $18 million and be completed in 1914.[84][85] The Municipal Art Commission ultimately approved the revised plans.[86]

Construction

Initial contracts

Excavations for the Astoria end of the main span, across Hell Gate, commenced in March 1911,

Work formally commenced on the Bronx and Queens approach viaducts in July 1912, and work on the foundations of the main span's towers began that September,

In November 1912, a New York Supreme Court justice enjoined the contractors from erecting abutments on Wards Island.[103][64] The operators of the Manhattan Psychiatric Center claimed that patients would be disturbed by loud noises, both during construction and after the bridge opened,[64] but the city government claimed that the hospital's lease of the island had expired.[104] The injunction was lifted in January 1913,[105] when the State Supreme Court ruled that the law permitting the bridge's construction overrode the law that restricted railroads above the grounds of a hospital.[86]

Pier construction

The construction of piers on Randalls and Wards Islands and in Queens began in February 1913.[94] Derricks were used to construct the concrete piers under the Bronx Kill, Randalls Island, Little Hell Gate, and Wards Island spans. The foundations of the Bronx Kill span's piers were constructed using caissons, since the underlying layer of rock was nearly 100 feet (30 m) deep.[101] The foundations of the Little Hell Gate span's piers were built in open cofferdams due to the shallowness of that strait.[106] The contractor built a dock on Wards Island to load and unload material. Derricks carried solid materials from the dock to a conveyor belts, which in turn led to covered storage bins, while cement was poured down a chute to a cement house next to the storage bins. Sand, stone, and cement from the bins were dumped into "charging cars" and carried to a mixing plant, where the material was mixed into concrete.[42] Elevators were used to transport concrete to the top of each pier.[96][86]

By July 1913, some of the piers and retaining walls for the Bronx and Queens viaducts had been constructed, and contractors had installed temporary plants on Randalls and Wards Islands.[96][107] The next month, the PRR and NH announced that the NYCR would issue a $30 million mortgage and $11 million in bonds to fund the construction of the Hell Gate Bridge and associated lines;[108] the railroads had spent $8.6 million to date on the bridge.[109] The bonds were issued later that year.[110] During a site visit in mid-1914, a local civic group noted that a temporary span had been finished across Bronx Kill and that piers were being built within the riverbed of Little Hell Gate.[111] The main span's towers had reached the height of the deck by the end of 1914, while almost all of the other piers had been completed by then.[112]

Steelwork and completion

Steel girders and plates for the Little Hell Gate and Bronx Kill spans were being installed by late 1914.[112] The girders under the two center tracks were installed first. Afterward, the center tracks were laid, and a derrick car and a locomotive crane were placed on opposite spans. The derrick car delivered girders that had already been riveted together, and the locomotive crane installed the girders for the outer tracks.[113] The arched main span above Hell Gate was technically challenging because Hell Gate was a navigable waterway, and the arch could not be constructed using falsework.[42][44] Consequently, massive temporary backstays were built behind both of the Hell Gate towers to cantilever the two pieces of the arch.[101][114][115] To accommodate the backstays, the tops of the towers and some adjacent piers could not be completed until after the Hell Gate span was finished.[114][116] After the backstays were constructed, movable derricks were installed atop the backstays.[117]

One thousand workers and 40 engineers began installing the steelwork of the arch in November 1914;[118] many of the laborers were Mohawk Native American ironworkers from Quebec and upstate New York.[119] Work proceeded in two sections from either shore toward the middle of Hell Gate.[118][120] The main span consisted of 23 panels,[118] which were installed by the derricks atop the backstays.[117] The panels were composed of steel pieces that weighed as much as 185 short tons (165 long tons; 168 t).[43][121] The steel pieces were manufactured off-site[102] and, at the time, were among the heaviest steel pieces ever manufactured.[122] Each piece was delivered to the site via car floats, then transported up via derricks.[117] To counteract sagging caused by the weight of the panels, both halves of the bridge occasionally had to be adjusted.[101] The project as a whole was declared half-finished in July 1915.[118] The last pieces of the lower chord were installed during the week of September 28 to October 4, 1915,[123][124] and both halves were officially joined on October 1.[102][125] The gap between the two parts of the arch was just 5⁄16 inch (7.9 mm).[102][123] The extreme precision was attributed to the level of detail in the engineering drawings,[116] as well as the use of highly precise surveying tools made by the W. & L. E. Gurley Company.[126]

The completion of the arch made the Hell Gate span the longest steel arch in the world.[125][120] The hydraulic jacks were removed from the towers,[122] and the backstays were disassembled and reused in the approach viaducts.[115][123] Workers began driving 400,000 rivets into the arched span;[123] Lindenthal claimed that they were among the largest rivets ever used.[102] Due to cold weather, the upper chord of the arch could not be riveted together until May 1916.[102] Locomotive cranes constructed the remaining portions of the viaducts.[2] By mid-October 1916, the PRR and NH anticipated that passenger service would commence at the beginning of 1917.[127] Finishing touches were placed on the bridge during late 1916.[128] In total, the bridge cost $18.5 million.[129] Before the bridge's official opening, police forces patrolled it to prevent sabotage during World War I.[130]

Operational history

Opening

The first train ran across the bridge at a dedication ceremony on March 9, 1917,[131][1] on a track constructed for the occasion.[132] The Hell Gate Bridge was not complete; workers were still laying tracks,[132] and the line was not electrified.[133] Intercity passenger trains began running on April 1[134] with the rerouting of the NH's Federal Express via the bridge.[135] The Hell Gate span was the world's longest steel arch bridge until the Bayonne Bridge, between New York and New Jersey, was completed in 1931.[136][137] Its completion enabled passengers to travel the length of the Northeast Corridor without having to transfer to a ferry.[6] Ammann initially estimated that the bridge would be mostly used by freight trains, because capacity constraints at Pennsylvania Station limited the bridge's two passenger tracks to 80 trains a day, and because most NH trains were planned to continue running to Grand Central.[138]

In mid-1917, NYCR applied for permission to issue $1.5 million in bonds to finish the bridge.[139] The bridge started carrying other routes in late 1917, such as the PRR's Colonial Express, the Washington-Bar Harbor Express,[140] and a short-lived St. Louis–Pittsburgh–Boston route.[141] Commuter services continued to run to Grand Central Terminal.[142][143] Though the bridge only carried rail traffic when it opened, it could also be adapted for pedestrian and car traffic.[144] By the end of 1917, all four tracks were complete,[145][146] and freight trains began running across the bridge in January 1918.[147] At the time, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote that the bridge would be able to accommodate 240 freight cars daily.[148] The passenger tracks were also electrified by 1918.[149]

During World War I, when the federal government took control of railroad lines in the U.S., the New York Central began using the Hell Gate Bridge,[150] allowing Long Island merchants to send products[151] The bridge was carrying only four passenger trains per day by September 1918, amid the war.[143] The media wrote that, due to its low use, the bridge's construction cost was unlikely to be recouped.[143][152] As late as 1919, the bridge was still carrying very limited passenger service because of wartime restrictions that diverted train traffic.[153] The New York Central stopped using the bridge in November 1920 after the PRR and NH raised the bridge's freight-transport fees,[154] and the New York Central began using car floats to Long Island instead.[150][151]

1920s proposals

When the

Meanwhile, the

In early 1926, the Port Authority asked the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to allow all freight trains on the bridge.[176] The PRR and NH again opposed the move,[177] and the PRR argued that allowing other railroads' trains on the bridge would discourage railroads from improving routes used by competitors.[178] ICC examiners recommended opening the bridge only to freight trains toward Long Island;[179][180] at the time, traffic to Long Island constituted 88 percent of the island's freight traffic volume.[181] The Port Authority continued to advocate for allowing all railroads to use the bridge in both directions.[179][182] The freight tracks were electrified in 1927.[183][184] The Port Authority also asked the ICC to lower the fees charged on freight trains using the bridge. The ICC ruled in 1928 that the railroads were not required to lower their rates but that they were required to allow other railroads to use the bridge during emergencies or when other routes were congested.[185]

1930s to 1960s

By 1932, residents of Long Island were advocating for the construction of a second rail link between their island and the Bronx, due to the lack of direct freight service to eastern Long Island via the Hell Gate Bridge.[186] The same year, the ICC hosted hearings over whether to run passenger trains over the bridge between eastern Long Island and New England;[187] the ICC ultimately rejected a Long Island–New England passenger train as impractical, inconvenient, and of little benefit.[188] In 1934, the NH put up its share of the bridge as collateral for a $6 million loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation; the NH was allowed to take back its portion of the bridge even if the RFC foreclosed on the loan.[189]

During World War II, in 1940, officials disarmed a live bomb under the Hell Gate Bridge.[190] The bridge's economic value made it a target of Operation Pastorius, a Nazi sabotage plan,[191] which was thwarted in 1942.[192] The NYCR began leasing out land around the bridge's approach viaducts to nearby property owners in the 1940s.[193] The property owners paid an annual fee and were obliged to maintain the land.[193][194] Additionally, passengers had to pay a surcharge on tickets for train trips that used the bridge, unless they were traveling to or from New York City; the surcharge had raised an estimated $20.9 million for the bridge from 1920 to 1950.[195] The surcharge prompted investigations from the ICC in the mid-1940s and again in 1951,[196] but the surcharge was upheld both times.[197]

Train traffic in the U.S. started to decrease in the mid-20th century as a result of increased automobile usage. This adversely affected both of the NYCR's co-owners and caused the bridge to fall into disrepair.

1970s to 1990s

The New Jersey car float was closed for an extended period during the 1970s, making the Hell Gate Bridge the only way for freight trains to get to and from Long Island during that time.[206][207] One of the bridge's freight tracks was abandoned during that decade as well.[198] The lack of rail crossings of the Hudson River, to the west, also meant that freight trains from Long Island had to detour to upstate New York just to travel west or south.[207] Freight trains from the west also had to make several tight turns to reach the Hell Gate Bridge.[208] New York state voters approved a bond issue in 1974, which provided $250 million for numerous upgrades to New York City's railroads.[209] The upgrades included modifications to allow double-stack freight trains to use the Hell Gate Bridge, thereby reducing the need for cargo trucks to travel through the city.[209][210]

Amtrak took over the bridge itself, and the passenger services that used it, in the 1970s,[211] while Conrail began operating additional freight trains during the same decade.[212][198] Vandals frequently threw rocks from the bridge and set fires, which had prompted Penn Central, and later Amtrak, to increase security on the bridge.[211] By the late 1970s, debris was falling from the approach viaducts.[194][213] Due to poor drainage, water had seeped through the viaducts, causing rocks to come loose.[214] City councilman Peter Vallone Sr. and U.S. representative Mario Biaggi advocated for Amtrak to repair the viaducts, saying the conditions threatened local residents' lives.[214] Amtrak started repairing the viaducts in 1978 but paused the repairs the next year.[215] When the project resumed in 1980,[216] workers added welded steel plates on the trackbeds to prevent objects from falling.[217] Even after the repairs were finished, local residents continued to express concerns about the viaduct's structural integrity.[218][219] Additionally, the bridge's paint was peeling off by the late 1980s.[220][221] Sources disagree on whether the bridge had last been repainted in 1939[222] or whether it had never been repainted at all;[219][221] in either case, Amtrak's own vice president said the bridge should have been repainted three times in the previous half-century.[222]

Vallone asked the federal government to fix the bridge after falling debris broke a car's window in 1988.[213] Vallone and U.S. senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan requested that Amtrak devise a plan for repairing the bridge,[223] though Amtrak officials denied that there was deterioration.[222][224] The New York Times described the bridge in 1991 as "a flaking and crumbling symbol of urban decay and decline".[225] Moynihan convened a United States Senate hearing in 1990 after attempting to contact Amtrak officials about the bridge; at the hearing, Amtrak officials testified that the bridge did not need repainting.[213][226] The officials also estimated the cost of repainting at $43 million, though Moynihan disputed these estimates.[213] By then, city officials had issued several warnings to pedestrians and drivers about the bridge's safety.[227] The United States Congress allocated $55 million to renovate the bridge in late 1991,[225][228] which included $42 million for repainting and $13 million for structural improvements.[229] In exchange, the New York State Department of Transportation had to provide matching funds for 20 percent of the federal allocation. At the time, 20 Amtrak trains used the bridge every day.[229]

Workers began renovating the bridge in April 1992;

2000s to present

In the first decade of the 21st century, the bridge carried around 41 passenger trains per weekday, as well as less frequent freight-train service.[233] Debris still fell from the bridge's approach viaducts due to both vandalism and general neglect,[239][240] and Vallone said in 2001 that the paint had started to peel off.[241][242] Security on the bridge was increased following the September 11 attacks.[243] In 2002, state government officials announced plans to spend $11.8 million to replace the bridge's freight track so it could support heavier trains.[244] After Peter Vallone Jr. was elected to his father's city council seat, the younger Vallone also unsuccessfully requested that Amtrak repaint the bridge throughout much of the 2000s.[220][245] Following further reports of cracks and falling debris,[246] Amtrak workers installed steel plates on the trackbed in the mid-2000s.[247] Amtrak proposed raising rental fees for the land under the bridge's approach viaducts in 2006, in some cases as much as 100,000 percent.[193] Following further lobby from the younger Vallone, Amtrak agreed to repair parts of the approach in 2008.[248]

The bridge's paint continued to fade during the 2010s.[220] Local residents also requested that Amtrak add more lighting to the bridge, which was illuminated at night by a small number of lights below the deck.[234][249] By early 2016, several local politicians were advocating for Amtrak to repaint the bridge in advance of its centennial, citing the fact that various parts of the spans had become discolored.[250] That year, Amtrak increased rental fees for the land under the bridge from tens of dollars to as much as $40,000 a year.[251] The railroad reversed the rent increases following outcry from local residents.[252] The Greater Astoria Historical Society, in conjunction with Amtrak, celebrated the centennial of the bridge's opening in 2017.[253][254] As part of Penn Station Access, in the 2020s, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) upgraded the Hell Gate Line to accommodate the Metro-North Railroad's New Haven Line; this required long-term interruptions to bridge traffic.[233]

Description

The Hell Gate Bridge was originally known as the New York Connecting Railroad Bridge

The Hell Gate Bridge is used exclusively as a railroad bridge, carrying passenger trains traveling between New York Penn Station and the Bronx, as well as freight trains heading between Queens and the Bronx.[266][267] The Hell Gate Bridge parallels the Hell Gate and Bronx Kill legs of the Robert F. Kennedy (formerly Triborough) Bridge to the west.[268] The span across Hell Gate is oriented roughly from northwest to southeast, while the other two spans are oriented from northeast to southwest.[269] The bridge was built with provisions for an upper level if the need arose.[138] The entire bridge required 90,000 short tons (80,000 long tons; 82,000 t) of steel and 460,000 cubic yards (350,000 m3; 12,000,000 cu ft) of concrete.[94][270][271] The decks of each span are all made of concrete panels, which carry track beds with ballast; this was intended to reduce noise pollution.[272] The February 2005 issue of Discover magazine estimated that, if humans were to disappear, the bridge could last for at least a millennium; most other bridges would fall in about 300 years.[273]

Main span

The main span is a spandrel arch across the Hell Gate strait,[46] flanked by large stone towers on either bank of the strait.[99][274] When the main span was completed, it was sometimes referred to specifically as the Hell Gate Bridge[256] or as the East River Arch Bridge.[225]

Arch and deck

The main span measures 1,017 feet (310 m) long between the outer faces of the masonry "towers" on either side of Hell Gate.

The span is a two-hinged arch; there are hinges at the springing points of the arch (at the bases of the towers on either side of Hell Gate).[2][117][263] The arch's beams run along the north and south sides of a 60-foot-wide (18 m) deck.[42][276] On either side of the deck is an upper chord, with an inverted U-shaped cross section, and a lower chord, with a box-shaped cross section.[277] The two chords are 140 feet (43 m) apart at either shore of Hell Gate, narrowing to 40 feet (12 m) apart at the middle of the river.[42][276] Each lower chord ranges in thickness from approximately 7 to 11 feet (2.1 to 3.4 m),[263][277] and the thickest sections of the lower chord are divided into two compartments.[101][121] The upper chord is thinner and functions like a stiffening truss.[263] The upper chord is shaped like a hump,[47][86] both for structural reinforcement and for esthetic purposes.[47] It reaches a maximum height of 300 feet (91 m)[278] or 305 feet (93 m) above mean high water.[2][274][279] Beams run vertically and diagonally between the upper and lower chords.[117][276] There is also transverse bracing between the upper chords and lower chords on either side of the bridge.[280]

Eight stringers run parallel to, and under, the tracks for the entire length of the deck. Four additional stringers were intended to support unbuilt walkways or trolley tracks on either side.[121][280] These are intersected by 24 transverse floor beams. Sixteen of the transverse beams are suspended from the lower chord, while the other eight beams are riveted to the vertical trusses between the lower and upper chords.[121] Additional girders are used to stabilize the floor of the deck.[281]

Towers

Hornbostel was responsible for the towers on either shore of Hell Gate, which were designed to resemble castle keeps.[2] They measure 220 feet (67 m) high and are made of concrete; the towers are clad with Maine granite above ground level.[99] At the bases of each tower are two 500,000-pound (230,000 kg) cast-steel hinges, one for each of the lower chords.[102] The Queens tower sits atop a layer of rock 20 feet (6.1 m) below the ground.[99][86] The layer of rock under the Wards Island tower is substantially deeper, descending more than 100 feet (30 m), and sits atop a deep caisson foundation.[100][99] At ground level, the towers have a cross section of 104 by 140 feet (32 by 43 m).[100][96] Each tower has a "shoulder", upon which the lower chords rest, and the towers' dimensions shrink above this shoulder.[86]

The upper portions of each tower are hollow and contain staircases.[233][282] Steel girders inside the towers support the tracks,[282] but the towers are otherwise largely ornamental.[233] The upper section of each tower contains archways on all four sides. There are also loophole-like openings flanking the tracks. The tops of the towers are surrounded by parapets.[2][282] Space for railroad equipment, such as switch tower machinery, was provided on the roof of each tower.[256]

Randalls and Wards Islands viaducts

Northwest of the Hell Gate span, the viaduct curves about 90 degrees to the northeast,

The viaduct ramps down as it continues north from Wards Island to Randalls Island.[106] The original plans for the piers called for them to be made for steel lattices.[2][60] The metal piers were changed to concrete both because the Municipal Art Commission disapproved of the steel-lattice design,[256] and because there were concerns that prisoners and psychiatric patients could escape by climbing the trestles. In addition, when the plans for the piers were changed in 1914, metal had become more expensive than concrete.[2]

Little Hell Gate Bridge

The bridge is supported by three piers, which are skewed because they follow the former course of Little Hell Gate. Each pier is composed of a reinforced concrete arch held up by two circular columns. The portion of each pier below the former strait's water level is made of granite.

Bronx Kill span

A 350-foot (110 m) fixed truss bridge crosses the Bronx Kill strait.

The Bronx Kill span was planned as a double-leaf bascule drawbridge, although the Bronx Kill was not a navigable waterway even at the time of the bridge's construction. As such, the piers under the span had space for drawbridge machinery,[284] and the span had a clearance below of 63 feet (19 m).[86] Underneath the Bronx Kill span is the Hell Gate Pathway, which continues underneath the Randalls and Wards Islands viaducts.[287]

Approach viaducts

The height of the arch above Hell Gate required that the line be placed on an elevated viaduct between Long Island City and Port Morris. The viaduct is almost entirely composed of steel and concrete, except for small segments at either end, where the line is carried on an embankment with retaining walls.[269] The steel viaduct is carried on approximately 150 concrete piers.[271]

Bronx viaduct

In the Bronx, the Hell Gate Bridge has an approach viaduct measuring 4,356 feet (1,328 m) long

From the Bronx Kill north to 132nd Street, the four-track-wide viaduct consists of plate girders, which rest on concrete piers. Each pier is less than 50 feet (15 m) tall and has an arched opening at the base.[284] The Hell Gate Pathway runs underneath the arches.[287] The viaduct splits into two ramps north of 132nd Street, each with space for two tracks.[284] Between 132nd and 138th Street, the ramps are largely supported by rectangular concrete piers.[284] The plate girders run parallel to each other, under the tracks, and are intersected perpendicularly by I-beams, which support the concrete-and-ballast trackbeds above.[290] The western ramp crosses over the Port Morris Branch's former eastern pair of tracks from 132nd to 133rd Street and is supported by large steel cross-girders.[290] Between 138th and 142nd streets, the line is carried on an embankment measuring 900 feet (270 m) long.[284]

Queens viaduct

The Queens approach viaduct descends at a grade of no more than 0.72 percent and is carried over local streets.[269][258] It ranges from 110 to 30 feet (33.5 to 9.1 m) above ground.[258] The section west of 29th Street measures 2,868 feet (874 m) long and was originally known as the Long Island viaduct.[117] The western viaduct is very similar to those above Randalls and Wards Islands, but the piers of the use shallow foundations due to the presence of gravel and sand under the viaduct. The gravel and sand could not accommodate loads of more than 3 short tons per square foot (29 t/m2), so the Queens viaduct is supported by especially wide concrete piers.[99]

The section from 29th to 44th Street

East of 44th Street, the viaduct ends, and the line descends onto an embankment.[258][291] The passenger and freight tracks branch off in western Queens, past the end of the viaduct.[57]

Usage

The bridge carries two

Services

Passenger rail

The bridge's two western tracks are part of the

In 1962, a regional transportation committee proposed running commuter rail trains from Connecticut to New York Penn Station via the Hell Gate Bridge,[202] in advance of the 1964 New York World's Fair.[303] The proposal was again studied in 1969[304] and 1973,[203] but the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) initially dismissed the commuter-rail plan as infeasible.[305] A plan to run some New Haven Line trains over the bridge was again proposed in the 1990s;[306] the main obstacle to the plan was a lack of track space at Penn Station.[238] The MTA studied the plan in 2000s as part of the Penn Station Access project, along with new stations on the Hell Gate Line in the Bronx.[307][308] Amtrak and the MTA reached an agreement regarding track usage rights in 2019,[309][310] and construction on Penn Station Access commenced in 2022, after the completion of East Side Access freed up space at Penn Station.[311] As of 2023[update], New Haven Line trains were expected to begin running to Penn Station in 2028.[312]

There have been proposals for the bridge to carry

Freight rail

On the eastern side of the bridge is the New York Connecting Railroad's single-track line, which links New York City and Long Island to the North American mainland.

Electrification

As completed, none of the bridge's four tracks had electrification.[133] Although the passenger tracks were electrified by 1918,[149] some steam locomotives continued to travel across the bridge through the 1920s.[316] Freight trains had to switch between electric and steam-powered locomotives at Oak Point Yard.[317] The New York State Legislature passed the Kaufman Act in 1923, mandating the electrification of all railways in New York City, including the freight routes on the Hell Gate Bridge, by January 1, 1926.[318] The freight tracks were still not electrified in late 1925,[175] but the NH was allowed to continue using the bridge[319] and was given until mid-1928 to fully electrify the line.[320] Electric freight service began in July 1927.[183] As a result of electrification, freight trains from Bay Ridge could travel as far east as Cedar Hill Yard in New Haven, Connecticut, without stopping.[184][317] The freight route was de-electrified in 1969, and the overhead wire above the freight tracks was removed.[205]

The passenger tracks were originally electrified using a 11 kV, 25 Hz

While NH trains were capable of operating on third rail power through the East River Tunnels to Penn Station, there was no third rail on the bridge.[138][149] Overhead catenary poles are instead installed along the length of the Hell Gate Bridge.[327] Power is supplied by substations along the Hell Gate Line. During the winter, the catenary wires could be defrosted by increasing the current coming from the substations.[328]

Fees and surcharges

Fees were originally charged on freight trains that used the Hell Gate Bridge. For instance, in the 1910s, the New Haven Railroad charged a fee of three cents for every 100 pounds (45 kg) of cargo that was transported via the bridge, a fee that was raised to five cents after World War I.[150]

During World War I, passengers began paying a fee on trips that used the bridge.[329] The surcharge, imposed on all passengers who were not departing or arriving at New York Penn Station, was originally 75 cents but was raised to 90 cents in 1920. To avoid the surcharge, passengers transiting through New York City frequently chose to buy a ticket from their original departure point to Penn Station, then another from Penn Station to their destination.[196] This prompted a complaint in 1945, in which a traveler claimed that the fee was discriminatory;[330] an ICC examiner recommended that the PRR and NH stop charging the fee,[329][331] but the ICC rejected the recommendation.[332] The ICC launched another inquiry into the surcharge in 1951.[195][196] ICC commissioner J. Monroe Johnson recommended in 1954 that the surcharge either be applied to all rail trips or be abolished entirely,[333] but the ICC also rejected the proposal.[197]

Impact

Critical reception

When the bridge was being built, The New York Times wrote that the bridge's abutments would dwarf the buildings on Wards Islands but that "it will give the idea of lightness and symmetry as well as almost immovable strength".[97] Hornbostel said the main span would "form a veritable triumphal arch at the northerly entrance of the Port of New York",[86] while the Railway Gazette called the project "second in interest only to the Quebec Bridge" due to its length.[334] After the main arch was completed, a writer for the New-York Tribune said: "Perhaps never in human history has a mechanical triumph of such magnitude been launched with so little fanfare",[122] while Outlook magazine described it as being "of interest in both the scientific world and in the world of transportation".[120] A writer for The American Architect magazine said in 1920 that "there is something picturesque about the long viaduct leading to Hell Gate Bridge".[335]

A 1972 almanac described the Hell Gate Bridge as one of 84 "notable modern bridges" across the world.[336] Jeffrey Kroessler and Nina Rappaport, the authors of the 1990 book Historic Preservation in Queens, described the Hell Gate Bridge as one of 35 structures in Queens that they believed were worth designating as official New York City landmarks.[337] At the end of the 20th century, the Engineering News-Record wrote that, "Its name notwithstanding, Hell Gate Bridge over the East River in New York City is considered to be one of the world's most beautiful bridges."[263]

In 2004, Joe Greenstein of Trains magazine described Amtrak passengers' view from the bridge as the "spectacular reward for enduring the cramped chaos of Penn Station",[338] but that the bridge was rarely noticed by those on the ground.[243] A writer for the same magazine called the Hell Gate Bridge "one of the most impressive and important railroad structures in America" in 2007.[339] At the bridge's centennial, Greater Astoria Historical Society director Bob Singleton called the Hell Gate Bridge "a school for 20th-century bridge making" and attributed the bridge's relative obscurity to the fact that it did not accommodate vehicles or pedestrians.[253] According to Amtrak's deputy chief structural engineer, Jim Richter, the bridge was "a great symbol of the railroad".[340]

Effect on development and commerce

When the Hell Gate Bridge and the NYCR line were proposed, the Brooklyn Times reported that the bridge and line would shift New York City's freight rail traffic from Manhattan to Brooklyn,[341] and PRR president Alexander Cassatt said the project would be second only to the Panama Canal in its impact on trade.[342] The bridge would also enable residents of towns along the New Haven railroad to commute to Penn Station,[343] at a time when the railroad used Grand Central Terminal to access Manhattan.[26] The New-York Tribune wrote in 1908 that, "for the first time in the history of this city, [there will be] an all-rail route through New York between New England and the South".[344] After work had begun, The New York Times called the bridge and the NYCR line "one of the greatest improvements under way toward the industrial development of Queens",[345] while the Sun said the bridge would increase Long Island's population and economy by making Queens into an industrial hub.[346] The Times also predicted in 1913 that the bridge's completion would increase real-estate values in western Queens and the South Bronx.[96]

When the bridge was completed, various houses and other buildings were constructed underneath the bridge's approach viaduct, particularly in Queens.[347] The Brooklyn Daily Eagle predicted that the completion of the bridge, along with the proposed Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel, would reduce shipping times to and from Brooklyn by a full day.[348] The Railway Age Gazette similarly predicted that freight rail would benefit most from the Hell Gate Bridge.[152] When the bridge opened, business owners negotiated for space near LIRR yards in western Queens, owing to these yards' proximity to the bridge.[127]

Influence and media

Railway Age wrote in 1955 that the Hell Gate Bridge had signified "the advent of steel arch construction" for railroad bridges.[349] Its design influenced the designs of others around the world.[198] The Sydney Harbour Bridge in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, was heavily influenced by the Hell Gate Bridge.[340][350] The engineer in charge of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, John Bradfield, had surveyed the Hell Gate Bridge while trying to come up with designs for the Sydney crossing.[350] The design of the Tyne Bridge in Newcastle upon Tyne, England, was derived from the Sydney Harbour Bridge and, by extension, the Hell Gate Bridge.[285][350] The McKees Rocks Bridge near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was also modeled on the Hell Gate Bridge.[351]

When the bridge was completed, the architect Hugh Ferriss drew a cover for the Queens Chamber of Commerce's monthly magazine Queensborough, which depicted the main span.[145] The main span was depicted in movies such as the 1973 film Serpico[352] and the 1991 film Queens Logic,[352][353] as well as TV shows such as Orange Is the New Black.[354] The bridge's name inspired the name of the 2000 film Under Hellgate Bridge by Michael Sergio.[355] In addition, the bridge has inspired works of art such as Hell Gate, a 28-foot-long (8.5 m) model of the main span by the artist Chris Burden.[356] The New York Botanical Garden's annual Christmas train show also includes a replica of the Hell Gate Bridge.[357]

See also

- List of bridges and tunnels in New York City

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in New York

- Rail freight transportation in New York City and Long Island

References

Notes

- ^ New York New Jersey Rail, LLC.[296]

- ^ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle gives a slightly different measurement of 87 to 90 feet (27 to 27 m).[86]

- ^ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle gives a slightly different measurement of 22 spans, measuring 80 feet (24 m) long.[86]

- ^ The Railway Age Gazette refers to this segment as running between "Lawrence Street and Stemler Street".[291] These streets have respectively been renamed 29th and 44th streets.[292]

Citations

- ^ ISBN 9780988691605.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Oviatt-Lawrence, Alice (February 22, 2024). "Engineering History". Structure magazine. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ ProQuest 1114484502.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ New York (State). Legislature. Senate (1914). Documents of the Senate of the State of New York. p. 448. Archived from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 570854593.

- from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Trunk Railroad Bridge Assured". Times Union. May 4, 1900. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Thrall & Billington 2008, p. 6.

- ^ ProQuest 570918041.

- from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 570809112.

- ProQuest 570822938.

- ProQuest 126796918.

- ^ ProQuest 535410650.

- ^ a b Ammann 1918, pp. 1654–1656.

- ^ a b "Transportation Problems". The Sun. March 21, 1909. p. 50. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Ammann 1918, p. 1659.

- ProQuest 570933874.

- ^ from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024; "Work on Connecting Road". The Brooklyn Citizen. April 12, 1902. p. 1. Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 2577-9397. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com; "Jacobs' Tunnel Plan Solves the Problem". Times Union. December 12, 1901. p. 1. Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Immense Railway Plan Behind Franchise for a Few Miles of Track". The Port Chester Journal. July 2, 1903. p. 6. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Penn. Tunnel Means Much to Long Island". Times Union. December 17, 1902. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024; "Plans Complete for the Great Ten-Million-Dollar Bridge and Viaduct to be Built Across Hell Gate". The Evening World. February 11, 1903. p. 6. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com; "Hell Gate Bridge Boom for Brooklyn". The Brooklyn Citizen. February 10, 1903. p. 1. Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 2577-9397. Archived from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com; "Pennsylvania Bridge Now". The Sun. June 12, 1903. p. 9. Archivedfrom the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 571528184.

- ^ from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ProQuest 571463832.

- ^ a b Ammann 1918, p. 1668.

- ^ a b c d e f Railway Age Gazette 1914, p. 890.

- ^ ProQuest 502726608.

- ^ a b Ammann 1918, p. 1663.

- ^ a b Ammann 1918, p. 1669.

- ^ a b c Thrall & Billington 2008, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c Thrall & Billington 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Ammann 1918, p. 1664.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024; "Talk of Veto for Aldermen Bill". The Standard Union. May 26, 1905. p. 3. Archivedfrom the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 571703067; "Connecting R. R. Fight Before R. T. Commission". The Brooklyn Citizen. November 17, 1905. p. 7. Archivedfrom the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "N. Y. C. R. R. Bills Signed". The Brooklyn Citizen. June 3, 1905. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 571688286.

- ISSN 1941-0646. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com; "Connecting R. R. Is Assured". The Sun. December 22, 1906. p. 1. Archivedfrom the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Ammann 1918, p. 1656.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 144742323.

- ^ ProQuest 866183708.

- ^ Mills, William Wirt (1908). Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels and terminals in New York City. Moses King. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 129229094.

- ^ from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 2577-9397. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com; "Bridge Plans Not Artistic". Times Union. July 29, 1907. p. 3. Archivedfrom the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ISSN 2577-9397. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com; "Bridge Will Be Longest in World". Press and Sun-Bulletin. December 21, 1908. p. 1. Archivedfrom the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 25, 2024. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- from the original on February 28, 2024. Retrieved February 28, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 28, 2024. Retrieved February 28, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Ammann 1918, p. 1672.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Hell Gate Bridge Begun". The Sun. March 24, 1911. p. 5. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 145129401.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 895747481.

- ^ a b "Greatest of All Railroad Bridges at Hell Gate a Link in New England-Western Railroad Route". Times Union. December 16, 1911. p. 18. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com; "Big Contract Will Furnish Work Here". Star-Gazette. November 4, 1911. p. 2. Archivedfrom the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ ProQuest 128359243.

- from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Building Piers for the Connecting Railroad". Times Union. October 26, 1912. p. 3. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Railway Age Gazette 1914, p. 891.

- ^ from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Great Hell Gate Bridge Triumph of Engineering". The Sun. September 26, 1915. p. 26. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "World's Heaviest Bridge Now Spans Hell Gate Tides". New York Herald. January 21, 1917. p. 45. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Doctors in Way of Connecting Railroad". Times Union. November 26, 1912. p. 8. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 2577-9397. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com; "Wards Island Is to Be Bridged". Times Union. January 17, 1913. p. 14. Archivedfrom the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Railway Age Gazette 1914, pp. 889–890.

- ProQuest 129418454.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 193288095.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ISSN 2577-9397. Archived from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com; "Long Island News". Times Union. May 13, 1914. p. 8. Archivedfrom the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Railway Age Gazette 1915, pp. 422–423.

- ^ a b Railway Age Gazette 1915, pp. 423–424.

- ^ a b "Queens Borough". Brooklyn Life. October 9, 1915. p. 24. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Railway Age Gazette 1915, p. 424.

- ^ a b c d "Biggest Bridge Half Finished". Times Union. July 20, 1915. p. 12. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Minthorn, David (August 18, 2002). "Exhibit celebrates Mohawks' high-rise feats". Star-Gazette. p. 28. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 136977172.

- ^ a b c d Railway Age Gazette 1915, p. 423.

- ^ from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 879810718.

- ProQuest 129466847.

- ^ ProQuest 548523866.

- ^ "Gurley company was once the Tiffany of surveying tools". Democrat and Chronicle. April 11, 1994. p. 13. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ProQuest 886551104.

- ^ Ammann 1918, p. 1662.

- from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ProQuest 886556136.

- ^ a b "Big Gang Laying Hell Gate R. R." Times Union. March 10, 1917. p. 8. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Over New Route". The Buffalo Commercial. March 10, 1917. p. 11. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ "Best Places to See NYC's Bridges : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. April 29, 1939. Archived from the original on November 8, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ProQuest 236899975.

- ^ a b c Ammann 1918, p. 1657.

- from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024; "More Hell Gate Trains". Times Union. April 18, 1917. p. 4. Archivedfrom the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 879777097.

- from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 129684267.

- from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "Hell Gate Bridge Plays Part in Troop Movements". Times Union. December 27, 1917. p. 6. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 865340475.

- ProQuest 509896338.

- from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Railway Age 1918, p. 1367.

- ^ from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "Port Authorities' Meeting Revives Hope Boro Will Get Adequate Transfer Lines". Times Union. September 28, 1925. p. 19. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 886557243.

- ProQuest 556721626.

- ProQuest 1112733514.

- ^ "Tri-Boro Bridge is "Uncalled For", Says Lindenthal" (PDF). Greenpoint Daily Star. February 19, 1920. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 19, 2024. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Hell Gate Span as a Vehicular Bridge Is Plan". The Brooklyn Citizen. December 13, 1926. p. 2. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on December 2, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- from the original on November 7, 2018. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- ^ "Port Authority Wants Hell Gate Bridge Put to Use". Times Union. June 20, 1924. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024; "L.I.R.R. Increases Yard Facilities as Probe Starts". Times Union. October 15, 1924. p. 2. Archivedfrom the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1113043882.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ProQuest 873968710.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ ProQuest 1113169584.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ProQuest 511852249.

- ^ ProQuest 557341351.

- ProQuest 1113618392.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024; "Urges Public Right in Hell Gate Span". Times Union. April 15, 1927. p. 11. Archivedfrom the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Railway Electrical Engineer 1928, p. 397.

- ^ ProQuest 896297024.

- from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ProQuest 1114851555.

- from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024; Manning, George H. (August 26, 1933). "Hell Gate Route Asked by Nassau Rejected by I.C.C." The Standard-Star. pp. 1, 2. Archivedfrom the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ProQuest 151278527.

- ISBN 0-1950-9268-6.

- from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c Gannon, Michael (September 1, 2016). "Astoria residents hit with Amtrak hikes". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ ProQuest 1237390911

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Healy, Ryan (February 22, 2016). "The Strange History Of NYC's Mighty Hell Gate". Gothamist. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ProQuest 179078084.

- ^ a b "Superhighway Urged in Place of New Haven's Harlem Line". Mount Vernon Argus. January 31, 1967. p. 17. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISBN 978-1-893122-08-6. Archivedfrom the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ProQuest 278397980.

- ^ a b c Cross Harbor Freight Movement Project in Kings, Queens, Richmond Counties, New York, and Hudson, Union, Middlesex, Essex Counties, New Jersey: Environmental Impact Statement. 2004. p. 10.

- ProQuest 123076962; Morris, Tom (October 18, 1978). "Piggyback Freight Center Eyed". Newsday. pp. 7, 28. Archivedfrom the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ ProQuest 964853600.

- ^ from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ ProQuest 278274630.

- ^ from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Jamieson, Wendell (July 7, 1988). "Debris From Bridge Still Falls on Astoria". Newsday. p. 33. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on January 10, 2015. Retrieved January 10, 2015.

- ^ from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Meeting to Discuss the Fate of Hell Gate Bridge". Newsday. November 2, 1988. p. 34. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 278372662.

- ProQuest 278412942.

- ^ a b "Work set to begin on Hell Gate bridge". Mount Vernon Argus. February 22, 1992. p. 13. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 428480105.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Greenstein 2004, p. 50.

- ^ a b Evelly, Jeanmarie (December 25, 2013). "Astoria Group Wants to Light Up Hell Gate Bridge". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Kern-Jedrychowska, Ewa (August 23, 2012). "Greek Gods to Adorn Hell Gate Bridge in New Mural". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on September 17, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ProQuest 203737509.

- ProQuest 313600816.

- ^ ProQuest 896790519.

- ProQuest 305581470.

- ^ Brownlow, Ron (October 13, 2005). "Falling Rocks Damage Cars Under Hell Gate In Astoria". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ProQuest 305647268.

- ^ Lippincott, E.E. (April 5, 2001). "Pols & Locals: Issues Continue To Plague Hell Gate Bridge". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Greenstein 2004, p. 51.

- ProQuest 896915591.

- ^ Duke, Nathan (December 19, 2009). "Repair Hell Gate: Vallone – QNS.com". QNS.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Bennett, Chuck (August 25, 2006). "Cracks in bridge cause for concern". Newsday. p. 16. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 306014209.

- ^ Toscano, John (March 26, 2008). "Long Overdue Hell Gate Bridge Repairs Getting Underway". Queens Gazette –. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024; "Amtrak to remove scaffolding – QNS.com". QNS.com. February 8, 2010. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ McRae, Tess (February 20, 2014). "Hell Gate Bridge may go to the light side". Queens Chronicle. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Matua, Angela (March 2, 2016). "Queens officials call for a paint job of Astoria's Hell Gate Bridge – QNS.com". QNS.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024; Ferry, Shannan (March 8, 2016). "Politicians, Local Leaders Call on Amtrak to Repaint Hell Gate Bridge". spectrumlocalnews.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024; Evelly, Jeanmarie (March 1, 2016). "Astoria's Hell Gate Bridge Should Be Repainted for 100th Birthday, Pols Say". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Pilgrim, Lexi (August 26, 2016). "Amtrak". The Real Deal. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024; Evelly, Jeanmarie (August 26, 2016). "Amtrak Hikes Rents For Backyard Spaces From $25 to $25K, Residents Say". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Christian, Lyndsay (November 4, 2016). "Amtrak Reverses Course on Rent Increase for Astoria Residents". Spectrum News NY1. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.Evelly, Jeanmarie (November 7, 2016). "Amtrak Drops Massive Rent Hikes on Backyards of Astoria Homeowners". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Barone, Vincent (March 27, 2017). "Hell Gate Bridge, an Astoria icon, turns 100 years old". amNewYork. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024

- ^ Calisi, Joseph M. (2017). "HELL GATE Hits 100". Passenger Train Journal. White River Productions. pp. 10–11; Evelly, Jeanmarie (March 9, 2017). "Astoria's Hell Gate Bridge Turns 100 This Week". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on December 25, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2011.

- ^ ProQuest 575472191.

- ^ a b "Facts of Longest Bridge in World". The Herald Statesman. October 12, 1915. p. 7. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ammann 1918, p. 1661.

- ^ a b Staff. "Growing a Bridge From Both Ends" Archived April 5, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, p. 769, The Literary Digest, Volume 51, No. 14, October 2, 1915. Accessed July 7, 2016. "The whole length of the structure (arch and two approaches), from abutment on Long Island to abutment in the Bronx, is 17,000 feet, or considerably over three miles."

- ^ a b Ammann 1918, p. 1660.

- from the original on February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Hopkins, Henry J. (1970). A Span of Bridges: An Illustrated History. New York, Praeger. p. 230.

- ^ ProQuest 235664917.

- ProQuest 1327224557.

- ProQuest 547614214.

- ^ a b "Celebrating the Hell Gate Bridge Centennial". Amtrak: History of America's Railroad. March 30, 2017. Archived from the original on February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ Brachfeld, Ben (January 30, 2023). "Dispute between MTA, Amtrak could delay Penn Access megaproject bringing Metro-North to west side". amNewYork. Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Railway Age Gazette 1914, p. 888.

- ^ from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Railway Age Gazette 1914, pp. 888–889.

- ProQuest 879802636.

- ^ Weisman, Alan (February 2005). "Earth Without People: What would happen to our planet if the mighty hand of humanity simply disappeared?". Discover. Archived from the original on March 28, 2023. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d Ammann 1918, p. 1651.

- ^ Hill, J.A.; Sinclair, A. (1922). Railway and Locomotive Engineering ... Angus Sinclair Company. p. 12. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c Ammann 1918, p. 1678.

- ^ a b Railway Age Gazette 1914, pp. 890–891.

- ProQuest 509758823.

- ^ Ammann 1918, pp. 1677–1678.

- ^ a b Ammann 1918, p. 1679.

- ^ Ammann 1918, pp. 1679–1680.

- ^ a b c Ammann 1918, p. 1682.

- ^ a b c Oviatt-Lawrence, Alice (February 22, 2024). "Gustav Lindenthal's Little Hell Gate Rail Bridge". Structure magazine. Archived from the original on February 24, 2024. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Railway Age Gazette 1914, p. 889.

- ^ a b "Tyne Bridge". BBC Inside Out. September 24, 2014. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2016.

Tyne Bridge was designed by Mott, Hay and Anderson... in turn derived its design from the Hell Gate Bridge

- from the original on November 1, 2023. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ a b "Randall's Island Park Highlights". The Hell Gate Pathway : NYC Parks. July 11, 2006. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ProQuest 879783320.

- ^ Ammann 1918, pp. 1660–1661.

- ^ a b Railway Age Gazette 1915, p. 422.

- ^ a b c Railway Age Gazette 1914, p. 892.

- ^ "Queens Table 1: Old Name to New Name". One-Step Webpages by Stephen P. Morse. Archived from the original on December 15, 2023. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Archivedfrom the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Railway Age Gazette 1915, p. 425.

- ^ Railway Age Gazette 1914, pp. 891–892.

- ^ a b c "Railroads in New York – 2016" (PDF). New York State Department of Transportation. January 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ Moody, J. (1926). Moody's Manual of Investments and Security Rating Service. Moody's Investors Service. p. 715. Archived from the original on March 1, 2024. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ProQuest 203891319.

- from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Going the Distance: Transportation Mobility in the New York Metropolitan Region" (PDF). Permanent Citizens Advisory Committee. October 2009. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 4, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Richterman, Anita (September 6, 1979). "Problem Line". Newsday. p. 151. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Good Transit Facilities Assured in Westchester". The Reporter Dispatch. January 15, 1963. p. 45. Archived from the original on March 7, 2024. Retrieved March 7, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ An Assessment of the Transit Service Potential of Inactive Railroad Rights-of-way and Yards Final Report. New York City Department of City Planning. October 1991. pp. 104, 128, 130.

- ISSN 2692-1251. Retrieved March 7, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 203891319.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Penn Station Access Study". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 2009. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ Castillo, Alfonso A. (January 22, 2019). "Metro-North riders will finally get Penn Station access". am New York. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Spivack, Caroline (January 22, 2019). "MTA to build new Metro-North stations linking Bronx to Penn Station". Curbed NY. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ "4 New Metro-North Stations Break Ground in NYC. Here's When They'll Take You to Penn". NBC New York. December 9, 2022. Archived from the original on December 9, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Brachfeld, Ben (January 30, 2023). "Dispute between MTA, Amtrak could delay Penn Access megaproject bringing Metro-North to west side". amNewYork. Archived from the original on January 30, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ISSN 2692-1251. Retrieved March 7, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Guse, Clayton; Nessen, Stephen (February 11, 2023). "Bronx is snubbed as MTA pursues IBX plan". Gothamist. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ProQuest 873956580.

- ^ a b Railway Electrical Engineer 1928, p. 398.

- ProQuest 873955742.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ProQuest 1112994213.

- ^ Railway Electrical Engineer 1928, p. 399.

- ^ Railway Age. Simmons-Boardman. 1928. p. 1099. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ Congressional Symposium, Railroads—1977 and Beyond—Problems and Promises. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1978. p. 61. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ProQuest 877749828.

- ISBN 978-0-7137-1718-1.

- ^ ISSN 0014-1380.

- ^ Railway Age 1918, p. 1368.

- ProQuest 879782454.

- ^ ProQuest 877761189.

- ProQuest 877760385.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ProQuest 879774443.

- ProQuest 1324201984.

- ProQuest 869227099.

- ProQuest 124684948.

- ISSN 2692-1251. Retrieved March 7, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Greenstein 2004, p. 49.

- ProQuest 206643782.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "To Centralize Business Interests on Long Island". Times Union. December 20, 1902. p. 9. Retrieved February 25, 2024 – via newspapers.com.