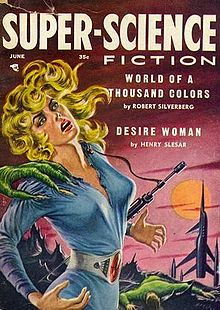

Henry Slesar

Henry Slesar | |

|---|---|

Mysteries | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 2 |

Henry Slesar (June 12, 1927 – April 2, 2002) was an American

Life

Henry Slesar was born in

It has been claimed that the term "coffee break" was coined by Slesar and that he was also the person behind

After

Afterwards, he opened his own agency.Slesar was married three times: to Oenone Scott, 1953–1969; to Jan Maakestad, 1970–1974; and to Manuela[4] Jone in 1974.[5] He had one daughter and one son.

Pseudonyms

In addition to writing chiefly under his own name, Slesar published under several pseudonyms, particularly on early short stories. These included:

- Clyde Mitchell – a Ziff Davis "house pseudonym" used by some science fiction and fantasy authors in Amazing Stories and Fantastic, which were edited by Paul W. Fairman. (Authors publishing as Clyde Mitchell include Robert Silverberg, Randall Garrett, Harlan Ellison, and others.) Slesar used the Mitchell name for "The Monster Died at Dawn" in Amazing Stories (November, 1956), and "A Kiss for the Conqueror" in Fantastic (February, 1957).

- O. H. Leslie – Slesar chose this name, which he used from 1956 to 1964, again for Paul Fairman as well as other magazines.

- In Amazing Stories he published such stories as "Marriages Are Made in Detroit" (December 1956), "Reluctant Genius"[8] (January 1957), "No Room in Heaven" (June 1957), and "The Anonymous Man" (July 1957), "The Seven Eyes of Jonathan Dark" (January 1959).

- In Fantastic he published such stories as "Death Rattle" (December 1956), "My Robot" (February 1957), "Abe Lincoln—Android" (April 1957), "The Marriage Machine" (July 1957), and "Inheritance" (August 1957).

- Ivar Jorgensen – This pseudonym, a house name, was also used by Robert Silverberg, Randall Garrett, Harlan Ellison, Howard Browne, and Paul Fairman himself. Slesar's use of the name appeared in Fantastic for "Coward's Death" (December 1956) and "Tailor-Made Killers" (August 1957).

- E. K. Jarvis – another Ziff Davis house name, also used by Robert Silverberg, Harlan Ellison, Paul W. Fairman, Robert Bloch, and Robert Moore Williams. Slesar used it for "Get Out of Our Skies!"[9] in Amazing Stories (December 1957).

- Lawrence Chandler – Another Ziff Davis house name, shared by Howard Browne, Slesar used it for "Tool of the Gods" in Fantastic (November 1957).

- Sley Harson – Nearly an anagram of Slesar's name, he used it in collaboration with his friend Harlan Ellison. Together they published "Sob Story" in The Deadly Streets (Ace Books, 1958).

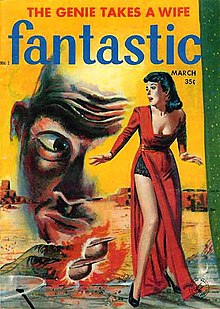

- Gerald Vance – Another Ziff Davis house name; shared by William P. McGivern, Rog Phillips, Robert Silverberg and Randall Garrett. Slesar sold the story "The Lavender Talent" to Paul Fairman at Fantastic (March 1958).

- Jeff Heller – A pen name he used when collaborating with his friend, M*A*S*H writer Jay Folb.[1]

- Eli Jerome - A pen name derived from the first names of his two brothers-in-law, the husbands of his sister Doris Greenberg and his sister Lillian Gleich. Used in stories in Alfred Hitchcock collections and 2 teleplays on Alfred Hitchcock Presents ("Party Line" and "One Grave Too Many", both 1960).

Other house names Slesar employed were Jay Street, John Murray, and Lee Saber.

After 1958, he wrote chiefly under his own name.

Career

In 1955, he published his first

He wrote a series of stories about a criminal named Ruby Martinson for Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine—"The First Crime of Ruby Martinson" (September, 1957), "Ruby Martinson, Ex-Con" (June, 1958), "Ruby Martinson, Cat Burglar" (June, 1959), "Ruby Martinson’s Great Fur Robbery" (May, 1962). He also penned the screenplay for the 1965 film Two on a Guillotine, which was based on one of his stories.

His first novel-length work was 20 Million Miles to Earth, a 1957

In 1974, he won an

He wrote mainly science-fiction scripts for the CBS Radio Mystery Theater during the 1970s.[11]

In 1983, Procter & Gamble wanted to replace him as the head writer for The Edge of Night, but ABC/ABC Daytime kept him. After his eventual replacement as head writer by Lee Sheldon, the network named him and Sam Hall the new head writers of its soap opera One Life to Live, but he left that show after only one year. He was later the head writer of the CBS Daytime series Capitol.

His last novel was Murder at Heartbreak Hospital (

Other late works included "interactive mystery serial" stories for MysteryNet.com, which invited readers to contribute their ideas.

Bibliography

Novels

- The Gray Flannel Shroud. New York: Random House, 1959. (Series: A Random House mystery)

- Enter Murderers. New York: Random House, 1960. (Series: A Random House mystery)

- The Bridge of Lions. New York: Macmillan, 1963.

- The Thing at the Door. New York: Random House, 1974. (ISBN 0-394-49007-X)

- Murder at Heartbreak Hospital. Chicago, Ill.: Academy Chicago Publishers, 1998.

Short fiction

- Collections

- Clean Crimes and Neat Murders: Alfred Hitchcock's Hand Picked Selection of Stories by Henry Slesar. Introduction by Alfred Hitchcock. New York: Avon, 1960.

- Cover title: A Bouquet of Clean Crimes and Neat Murders.

- Spine title: Alfred Hitchcock Presents Clean Crimes and Neat Murders.

- A Crime for Mothers and Others. New York, N.Y.: Avon, 1962.

- Murders Most Macabre. New York, N.Y.: Avon, 1986. (paperback; ISBN 0-380-89975-2)

- Death on Television: The Best of Henry Slesar's Alfred Hitchcock Stories. Edited by ISBN 0-809-31500-9)

- Stories[14]

| Title | Year | First published | Reprinted/collected | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deuce | 1991 | |||

| Examination Day | 1985 | |||

| The dinner party | 2001 | "The dinner party". F&SF. 100 (1): 59–65. January 2001. | ||

| The museum | 2000 | Slesar, Henry (March 2000). "The museum". F&SF. 98 (3): 128–140. |

- "A Cry from the Penthouse" (1959) – Originally published in Playboy, November, 1959. Anthologized in: Alfred Hitchcock Presents Stories for Late at Night, 1961 and AHP: More Stories for Late at Night, 1962.

- "A God Named Smith" (1957) – Originally published in ISBN 978-1-61287-078-6.

- "Abe Lincoln – Android" (1957) – As by O. H. Leslie. Originally published in Fantastic, April, 1957. Anthologized in: Great Science Fiction, No. 6, 1967.

- "Bats" (1989) – The Further Adventures of ISBN 0-553-28270-0.

- "Before the Talent Dies" (1957) – Originally published in ISBN 0-451-13201-7.

- "Behind the Screen" (1993) – The Further Adventures of ISBN 0-553-28624-2.

- "Brother Robot" (1958) – Originally published in ISBN 0-451-15926-8.

- "Chief" (1960) – The 6th Annual of the Year's Best S-F, 1961, ed. ISBN 0-380-50773-0; and others.

- "Cop for a Day" (1957) – Originally published in Manhunt, January 1957. Anthologized in: The Young Oxford Book of Nasty Endings, 1997, ed. Dennis Pepper, ISBN 0-19-278151-0.

- Slesar, Henry (January 1957). "Dream Town". Project Gutenberg EBook. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- "Ersatz" (1967) – Dangerous Visions, 1967, ed. Harlan Ellison.

- "Examination Day" (1958) – Originally published in ISBN 0-06-623842-0.

- "40 Detectives Later" – in 100 Menacing Little Murder Stories, 1998, ed. ISBN 0-7607-0854-1.

- Slesar, Henry (January 1957). "Heart". Project Gutenberg EBook. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- "I Now Pronounce You ISBN 0-553-28568-8.

- "Job Offer" (1959) – Originally published in ISBN 0-517-60669-0.

- "Legacy of Terror" (1958) – Originally published in Amazing Science Fiction Stories, November, 1958. Anthologized in: Satan's Pets, 1972, ed. Vic Ghidalia.

- "Lost Dog" (1958) – Originally published in Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, February, 1958. Anthologized in: Alfred Hitchcock Presents: Stories My Mother Never Told Me, 1963, ed. Alfred Hitchcock.

- "Murder Delayed" (1962) – Games Killers Play, 1968, ed. Alfred Hitchcock.

- "My Father, The Cat" (1957) – Originally published in ISBN 0-451-45061-2); and others.

- "My Mother the Ghost" (1965) – Originally published in ISBN 0-385-11416-8.

- "Personal Interview" (1957) – Originally published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine Including Black Mask Magazine, December 1957.

- "Prez" (1982) – Terrors, 1982, ed. ISBN 0-86721-138-5.

- "Speak" (1965) – First published in ISBN 0-7607-0118-0.

- "The Candidate" (1961) – Originally published in ISBN 0-19-278151-0; and others.

- "The Fifty-third Card" (1990) – The Further Adventures of The Joker, 1990, ed. Martin H. Greenberg, ISBN 0-553-28531-9.

- "The Girl Who Found Things" (1973) – Originally published in ISBN 0-87975-506-7.

- "The Goddess of World 21" (1957) – Originally published in Fantastic, March, 1957. Later in The Most Thrilling Science Fiction Ever Told No. 11, Winter 1968.

- "The Haunted Man" (1974) – Twisters, (981, ed. Steve Bowles, ISBN 0-00-671798-5.

- "The Invisible Man Murder Case" (1958) – Originally published in Fantastic, May 1958. Anthologized in: Invisible Men, 1960, ed. Basil Davenport; and in The Seven Deadly Sins of Science Fiction, 1981, ed. Isaac Asimov, Martin H. Greenberg, Charles G. Waugh.

- "The Jam" (1958) – Originally published in ISBN 0-688-10963-2; and others.

- "The Knocking in the Castle" (1964) – Originally published in Fantastic Stories of Imagination, November, 1964. Anthologized in: The Hell of Mirrors, 1965, ed. Peter Haining.

- "The Mad Killer" (1957) – Originally published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine Including Black Mask Magazine, June 1957.

- "The Movie-Makers" (1956) – Originally published in ISBN 0-8008-3197-7.

- "The Moving Finger Types" (1968) – Originally published in ISBN 1-56865-524-X.

- "The Old Man" (1962) – Microcosmic Tales, 1980, ed. Joseph D. Olander, Martin H. Greenberg, Isaac Asimov, ISBN 1-56731-065-6.

- "The Phantom of the Soap Opera" (1989) – Phantoms, 1989, ed. Rosalind M. Greenberg, Martin H. Greenberg, (DAW Collectors #778), ISBN 0-88677-348-2.

- "The Return of the Moresbys" (1964) – Haunted America: Star-Spangled Supernatural Stories, 1991, ed. Marvin Kaye.

- "The Right Kind of House" (1957) – Originally published in Haunted Houses: The Greatest Stories, 1997, ed. Martin H. Greenberg, ISBN 0-7607-0854-1.

- "The Secret Formula" (1957) – Originally published in Playboy, October, 1957.

- "The Secret of Marracott Deep" (1957) – Originally published in ISBN 978-1-61287-008-3.

- "The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Ross" (1961) – Originally published in ISBN 1-56731-065-6.

- "The Show Must Go On" (1957) – Originally published in ISBN 978-1-61287-028-1.

- "The Stuff" (1961) — Originally published in Galaxy Science Fiction, August 1961.

- "The Success Machine" (1957) – Originally published in Amazing Stories, September, 1957. Later appeared in Science Fiction Greats, Winter 1969, and in Fantastic, July, 1979.

- "Victory Parade" (1957) – Originally published in ISBN 0-688-41723-X.

- "Who Am I?" (1956) – Originally published in ISBN 978-1-893887-48-0.

- "Blackmailer" (1952) – Originally published in The Saint Mystery Magazine August 1952.

- "The Percent of Murder" (1958) - Originally published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine September 1958.

- "Not The Running Type" (1959) – Originally published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine January 1959.

- "The Horse That Was Not For Sale" (1964) – Originally published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine May 1964

- "The Haunted Man" (1974) – Originally published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine April 1974

- "The Memory Expert" (1974) – Originally published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine August 1974

- "The Bottle" (1986) – Originally published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine August 1986

- "Death in the First Edition" (1992) – Originally published by Waddington Games for the Clue Mystery Jigsaw Puzzle series

- "Whosit's Disease" (1962) – Originally published in ISBN 0-450-01297-2.

Plays

- The Veil. Studio City, CA: Players Press, 1997. (ISBN 0887342612)

Radio plays

- CBS radio mystery dramas (Numbers are show numbers)

- 0001 The Old Ones Are Hard to Kill

- 0002 The Return of the Moresbys

- 0004 Lost Dog

- 0014 The Girl Who Found Things

- 0015 The Chinaman Button

- 0019 Deadly Honeymoon

- 0021 The Ring of Truth

- 0032 After the Verdict

- 0045 The Horse That Wasn't for Sale

- 0047 A Choice of Witnesses

- 0058 Sea of Troubles

- 0070 The Locked Room

- 0071 The Murder Museum

- 0075 Men Without Mouths

- 0093 The Trouble with Ruth

- 0103 A Bargain in Blood

- 0110 Where Fear Begins

- 0126 The Hit Man

- 0134 The Final Vow

- 0135 The Hands of Mrs. Mallory

- 0138 The Case of M.J.H.

- 0149 Thicker than Water

- 0159 The Doll

- 0162 The Last escape

- 0169 Bury Me Again

- 0257 My Own Murder

- 0275 The Rise and Fall of the Fourth Reich

- 0303 The Slave

- 0329 Welcome for a Dead Man

- 0389 Promise to Kill

- 0429 You Owe Me a Death

- 0618 Jobo

- 0658 A God Named Smith

- 0663 The Night We Died

- 1038 The Movie Makers

- 1051 Prisoner of the Machines

- 1075 Kitty

- 1086 Two of a Kind

- 1089 The Bluff

- 1103 Murder Preferred

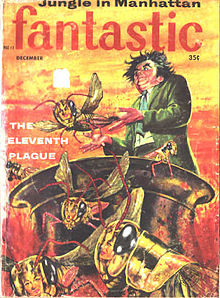

- 1136 The Eleventh Plague

- 1317 Shelter

- 1388 I Hate Harold

Teleplays

Most of the teleplays written for Alfred Hitchcock Presents were based on Slesar's own stories.

- "A Crime for Mothers", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, January 24, 1961 (Season 6, Episode 16), starring Claire Trevor and Patricia Smith.

- "A Woman's Help", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, March 28, 1961 (Season 6, Episode 24), starring Antoinette Bower.

- "Blood Bargain", for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, October 25, 1963 (Season 2, Episode 5), starring Richard Kiley.

- "Burglar Proof", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, February 27, 1962 (Season 7, Episode 21), starring Paul Hartman.

- "Cop for a Day", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, October 31, 1961 (Season 7, Episode 4), starring Walter Matthau and Glenn Cannon.

- "Final Vow" for, The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, October 25, 1962 (Season 1, Episode 6), starring Carol Lynley.

- "I Saw the Whole Thing", for The Alfred Hitchcock Hour, October 11, 1962 (Season 1, Episode 4), starring John Forsythe.

- "Laurie Marie", for The Name of the Game, December 19, 1969 (Season 2, Episode 13); teleplay written with David P. Harmon.

- "Ma Parker", for Batman, October 6, 1966 (Season 2, Episode 10).

- "Most Likely to Succeed", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, May 8, 1962 (Season 7, Episode 31).

- "The Greatest Mother of Them All", for Batman, October 5, 1966 (Season 2, Episode 9).

- "The Horse Player", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, March 14, 1961 (Season 6, Episode 22), starring Claude Rains.

- "The Last Escape", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, January 31, 1961 (Season 6, Episode 17), starring Keenan Wynn and Jan Sterling.

- "The Last Remains", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, March 27, 1962 (Season 7, Episode 25), starring John Fiedler.

- "The Man in the Mirror", for 77 Sunset Strip, January 13, 1961 (Season 3, Episode 18).

- "The Man with Two Faces", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, December 13, 1960 (Season 6, Episode 11), starring Spring Byington.

- "The Test", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, February 20, 1962 (Season 7, Episode 20), starring Brian Keith and Rod Lauren.

- "The Throwback", for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, February 28, 1961 (Season 6, Episode 20), starring Murray Matheson.

Adaptations

- "A Cry from the Penthouse" – Originally published in Playboy, 1959. Adapted for Markham (Season 1, Episode 52), starring Ray Milland, Jack Weston and Willard Waterman.

- "Bottle Baby" – Originally published in Fantastic, 1957; adapted (uncredited) as the feature film Terror from the Year 5000 (1958).[16]

- "The Day of the Execution" – Appeared in Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine Presents Fifty Years of Crime and Suspense. Adapted by Bernard C. Schoenfeld as "Night of the Execution" for Alfred Hitchcock Presents (Season 3, Episode 13), starring Pat Hingle.

- "Examination Day" – Originally published in Playboy, 1958. Adapted by Philip DeGuere for The Twilight Zone (Season 1, Episode 6), starring Christopher Allport, David Mendenhall, and Elizabeth Norment.

- "40 Detectives Later" – Adapted as Forty Detectives Later for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, 24 April 1960 (Season 5, Episode 28), starring James Franciscus, George Mitchell, and Jack Weston.

- "M Is for the Many" – Originally published in Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, 1957. Adapted as Heart of Gold by James P. Cavanagh for Alfred Hitchcock Presents (Season 3, Episode 4), starring Darryl Hickman.

- "Party Line" – Adapted by Eli Jerome for Alfred Hitchcock Presents (Season 5, Episode 33), starring Judy Canova.

- "Symbol of Authority" – Originally published in Donald Harron, Ernie Kovacs and Michael Landon.

- "The Right Kind of House" – Originally published in Haunted Houses: The Greatest Stories, 1997. Adapted by Robert C. Dennis for Alfred Hitchcock Presents (Season 3, Episode 23), starring Robert Emhardt and Jeanette Nolan.

- "The Self-Improvement of Salvadore Ross" – Originally published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, 1961. Adapted by Jerry McNeely for Twilight Zone, January 17, 1964 (Season 5, Episode 16), starring Don Gordon.

- "The Old Man in the Cave", based on his 1962 story "The Old Man," for Twilight Zone, November 8, 1963 (Season 5, Episode 7); teleplay written by Rod Serling.

Awards and nominations

In 1960, he was awarded the

Death

In 2002, he died of complications due to minor elective surgery.[1]

References

- ^ ISSN 0047-4959.

- ^ a b Schemering, Chris (1988). The Soap Opera Encyclopedia. Ballantine Books. p. 283.

- ^ Lucy, Jim (July 1, 2003). "The Man in the Chair Lives". Electrical Wholesaling. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ a b Hobbs, John (April 15, 2002). "Obituary: Henry Slesar". Variety. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ a b "Detectionary" (PDF). Detectionary. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

Militaire dienst: US Army, 1946–1947.

- ^ "Henry Slesar". Detective-Fiction.com. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ Slesar, Henry (April 17, 2008). "The Delegate from Venus [full text]". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ Slesar, Henry (February 9, 2009). "Reluctant Genius [full text]". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ Slesar, Henry (October 6, 2008). "Get Out of Our Skies! [full text]". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- ^ Schemering, Chris (1988). The Soap Opera Encyclopedia. Ballantine Books. p. 92.

In 1968 veteran mystery writer Henry Slesar became headwriter, beginning a writing stint of fifteen years, the longest in the history of daytime drama.

- ^ "Free Audio SF – CBS Radio Mystery Theater". Hard SF. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ "Murder at Heartbreak Hospital". Kirkus Reviews. November 15, 1998. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

This first US publication for a novel Slesar (The Thing at the Door, 1974, etc.) originally published in Europe in 1990 finds the veteran storyteller, whose TV credits go back to Alfred Hitchcock Presents, plotting murder in the world he used to work in, the hothouse universe of the soap opera.

- Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ Short stories unless otherwise noted.

- ^ "The Fiend in You (1962), An anthology of stories edited by Charles Beaumont". Fantastic Fiction website. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ "Category List – Best First Novel | Edgars Database". theedgars.com. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

External links

- Works by Henry Slesar at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Henry Slesar at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Henry Slesar at IMDb

- WhoDunnit

- Henry Slesar at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database