High Middle Ages

Europe and Mediterranean region

Europe and the Mediterranean region, c. 1190

|

|

- The Crusades

- (Solid Line) Second Crusade of Louis VII and Conrad III

- (Line and dot) Fredrick I

- Small map

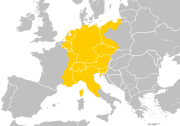

Central Europe

|

|

The High Middle Ages, or high medieval period, was the

Key historical trends of the High Middle Ages include the

From around 780, Europe saw the last of the

In the 11th century, populations north of the

The High Middle Ages produced many different forms of intellectual, spiritual and

The

Historical events and politics

Great Britain and Ireland

In England, the

Iberia

A key geo-strategic development in the

Italy

In Italy, with the Norman conquest, the first great and powerful state was formed, the Kingdom of Sicily with hereditary monarchy. Subsequently joined to the Holy Roman Empire, it had its moment of maximum splendor with the emperor Frederick II.

In the rest of Italy, independent city states grew affluent on Eastern Mediterranean maritime trade. These were in particular the thalassocracies of Pisa, Amalfi, Genoa and Venice, which played a key role in European trade from then on, making these cities become major financial centers.[18]

From the mid-10th to the mid-11th centuries, the Scandinavian kingdoms were unified and Christianized, resulting in an end of

France and Germany

By the time of the High Middle Ages, the Carolingian Empire had been divided and replaced by separate successor kingdoms called France and Germany, although not with their modern boundaries. France pushed to the west. The Angevin Empire controlled much of France in the 12th century and early 13th century until the French retook much of their previous territory.

Germany

By the time of the High Middle Ages, the Carolingian Empire had been divided and replaced by separate successor kingdoms called France and Germany, although not with their modern boundaries. Germany was significantly more eastern. Germany was under the banner of the Holy Roman Empire, which reached its high-water mark of unity and political power under Kaiser Frederick Barbarossa.

Georgia

During the successful reign of King

Hungary

In the High Middle Ages, the Kingdom of Hungary (founded in 1000), became one of the most powerful medieval states in central Europe and Western Europe. King Saint Stephen I of Hungary introduced Christianity to the region; he was remembered by the contemporary chroniclers as a very religious monarch, with wide knowledge in Latin grammar, strict with his own people but kind to foreigners. He eradicated the remnants of the tribal organisation in the Kingdom and forced the people to sedentarize and adopt the Christian religion. He founded the Hungarian medieval state, organising it politically into counties using the Germanic system as a model.

The following monarchs usually kept a close relationship with Rome, such as Saint

Lithuania

During the High Middle Ages Lithuania emerged as a Duchy of Lithuania in the early 13th century, then briefly becoming the Kingdom of Lithuania from 1251 to 1263. After the assassination of its first Christian king Mindaugas Lithuania was known as Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Unconquered during the Lithuanian Crusade, Lithuania itself rapidly expanded to the East due to conquests and became one of the largest states in Europe.

Poland

In the mid-10th century Poland emerged as a duchy after

Southeast Europe

The High Middle Ages saw the height and decline of the Slavic state of

During the first half of this period (c. 1025—1185) the

Climate and agriculture

The

The rise of chivalry

During the High Middle Ages, the idea of a Christian warrior started to change as Christianity grew more prominent in Medieval Europe. The Codes of Chivalry promoted the ideal knight to be selfless, faithful, and fierce against those who threaten the weak.[20] Household heavy cavalry (knights) became common in the 11th century across Europe, and tournaments were invented. Tournaments allowed knights to establish their family name while being able to gather vast wealth and renown through victories. In the 12th century, the Cluny monks promoted ethical warfare and inspired the formation of orders of chivalry, such as the Templar Knights. Inherited titles of nobility were established during this period. In 13th-century Germany, knighthood became another inheritable title, although one of the less prestigious, and the trend spread to other countries.

Religion

Christian Church

The

Crusades

The Catholic Crusades occurred between the 11th and 13th centuries. They were conducted under papal authority, initially with the intent of reestablishing Christian rule in The Holy Land by taking the area from the Muslim

Military orders

In the context of the crusades, monastic military orders were founded that would become the template for the late medieval

The Knights Templar were a Christian military order founded after the First Crusade to help protect Christian pilgrims from hostile locals and highway bandits. The order was deeply involved in banking, and in 1307 Philip the Fair (Philippine le Bel) had the entire order arrested in France and dismantled on charges of alleged heresy.

The

The

Scholasticism

The new

Golden age of monasticism

- The late 11th century/early-mid 12th century was the height of the golden age of Christian monasticism (8th-12th centuries).

- Benedictine Order– black-robed monks

- Cistercian Order– white-robed monks

Mendicant orders

- The 13th century saw the rise of the Mendicant orderssuch as the:

- Franciscans(Friars Minor, commonly known as the Grey Friars), founded 1209

- Carmelites(Hermits of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Carmel, commonly known as the White Friars), founded 1206–1214

- Dominicans (Order of Preachers, commonly called the Black Friars), founded 1215

- Augustinians (Hermits of St. Augustine, commonly called the Austin Friars), founded 1256

Heretical movements

Christian

Cathars

Catharism was a movement with

The name Cathar stems from

The Cathars are also called Albigensians. This name originates from the end of the 12th century, and was used by the chronicler Geoffroy du Breuil of Vigeois in 1181. The name refers to the southern town of Albi (the ancient Albiga). The designation is hardly exact, for the centre was at Toulouse and in the neighbouring districts.

The Albigensians were strong in southern France, northern Italy, and the southwestern Holy Roman Empire.

The

- Dualists believed that historical events were the result of struggle between a good (spiritual) force and an evil (material) force and that the world was of the evil force, though it could be controlled or defeated through asceticismand good works.

- Albigensian Crusade, Simon de Montfort, Montségur, Château de Quéribus

Waldensians

Peter Waldo of Lyon was a wealthy merchant who gave up his riches around 1175 after a religious experience and became a preacher. He founded the Waldensians which became a Christian sect believing that all religious practices should have strictly scriptural bases. Waldo was denied the right to preach his sermons by the Third Lateran Council in 1179, which he did not obey and continued to speak freely until he was excommunicated in 1184. Waldo was critical of the Christian clergy saying they did not live according to the word. He rejected the practice of selling indulgences (simony), as well as the common saint cult practices of the day.

Waldensians are considered a forerunner to the

Trade and commerce

In Northern Europe, the Hanseatic League, a federation of free cities to advance trade by sea, was founded in the 12th century, with the foundation of the city of Lübeck, which would later dominate the League, in 1158–1159. Many northern cities of the Holy Roman Empire became Hanseatic cities, including Amsterdam, Cologne, Bremen, Hanover and Berlin. Hanseatic cities outside the Holy Roman Empire were, for instance, Bruges and the Polish city of Gdańsk (Danzig), as well as Königsberg, capital of the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights. In Bergen, Norway and Veliky Novgorod, Russia the league had factories and middlemen. In this period the Germans started colonising Europe beyond the Empire, into Prussia and Silesia.

In the late 13th century, a Venetian explorer named Marco Polo became one of the first Europeans to travel the Silk Road to China. Westerners became more aware of the Far East when Polo documented his travels in Il Milione. He was followed by numerous Christian missionaries to the East, such as William of Rubruck, Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, André de Longjumeau, Odoric of Pordenone, Giovanni de' Marignolli, Giovanni di Monte Corvino, and other travellers such as Niccolò de' Conti.

Science

Philosophical and scientific teaching of the Early Middle Ages was based upon few copies and commentaries of ancient Greek texts that remained in Western Europe after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Most of them were studied only in Latin as knowledge of Greek was very limited.

This scenario changed during the Renaissance of the 12th century. The intellectual revitalization of Europe started with the birth of medieval universities. The increased contact with the Islamic world in Spain and Sicily during the Reconquista, and the Byzantine world and Muslim Levant during the Crusades, allowed Europeans access to scientific Arabic and Greek texts, including the works of Aristotle, Alhazen, and Averroes. The European universities aided materially in the translation and propagation of these texts and started a new infrastructure which was needed for scientific communities.

At the beginning of the 13th century there were reasonably accurate Latin translations of the main works of almost all the intellectually crucial ancient authors,

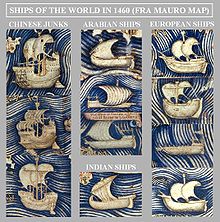

Technology

During the 12th and 13th century in Europe there was a radical change in the rate of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing traditional means of production, and economic growth. In less than a century there were more inventions developed and applied usefully than in the previous thousand years of human history all over the globe. The period saw major technological advances, including the adoption or invention of windmills, watermills, printing (though not yet with movable type), gunpowder, the astrolabe, glasses, scissors of the modern shape, a better clock, and greatly improved ships. The latter two advances made possible the dawn of the Age of Discovery. These inventions were influenced by foreign culture and society.

Alfred W. Crosby described some of this technological revolution in The Measure of Reality: Quantification in Western Europe, 1250-1600 and other major historians of technology have also noted it.

- The earliest written record of a windmill is from Yorkshire, England, dated 1185.

- Paper manufacture began in Italy around 1270.

- The spinning wheel was brought to Europe (probably from India) in the 13th century.

- The magnetic compassaided navigation, first reaching Europe some time in the late 12th century.

- Eye glasses were invented in Italy in the late 1280s.

- The astrolabe returned to Europe via Islamic Spain.

- Hindu-Arabic numerals to Europe with his book Liber Abaciin 1202.

- The West's oldest known depiction of a stern-mounted rudder can be found on church carvings dating to around 1180.

Arts

Visual arts

Art in the High Middle Ages includes these important movements:

- Anglo-Saxon art was influential on the British Isles until the Norman Invasion of 1066

- Romanesque art continued traditions from the Classical world (not to be confused with Romanesque architecture)

- Gothic art developed a distinct Germanic flavor (not to be confused with Gothic architecture).

- Indo-Islamic architecture begins when Muhammad of Ghor made Delhi a Muslim capital

- Byzantine art continued earlier Byzantine traditions, influencing much of Eastern Europe.

- Illuminated manuscriptsgained prominence both in the Catholic and Orthodox churches

Architecture

Gothic architecture superseded the

Literature

A variety of cultures influenced the literature of the High Middle Ages, one of the strongest among them being Christianity. The connection to Christianity was greatest in

Despite political decline during the late 12th and much of the 13th centuries, the Byzantine scholarly tradition remained particularly fruitful over the time period. One of the most prominent philosophers of the 11th century,

At the same time southern France gave birth to

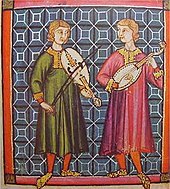

Music

The surviving music of the High Middle Ages is primarily religious in nature, since

During the 11th century, Guido of Arezzo was one of the first to develop musical notation, which made it easier for singers to remember Gregorian chants.

It was during the 12th and 13th centuries that Gregorian plainchant gave birth to polyphony, which appeared in the works of French

The most significant secular movement was that of the

Theatre

Economic and political changes in the High Middle Ages led to the formation of

There were also a number of secular performances staged in the Middle Ages, the earliest of which is The Play of the Greenwood by

Timeline

- 1054 – East–West Schism

- 1066 – Battle of Hastings

- 1073–1085 – Pope Gregory VII

- 1071 – Battle of Manzikert

- 1077 – Walk to Canossa

- 1086 – Domesday Book

- 1086 – Battle of az-Zallaqah

- 1088 – University of Bologna founded

- 1091 – Battle of Levounion

- 1096 – University of Oxford founded

- 1096–1099 – First Crusade

- 1123 – First Lateran Council

- 1139 – Second Lateran Council

- 1145–1149 – Second Crusade

- 1147 – Wendish Crusade

- c. 1150 – University of Paris founded

- 1155–1190 – Frederick I Barbarossa

- 1159 – foundation of the Hanseatic League

- 1169 – Norman invasion of Ireland

- 1185 – reestablishment of the Bulgarian Empire

- 1189–1192 – Third Crusade

- 1200–1204 – Fourth Crusade

- 1205 – Battle of Adrianople

- 1209 – University of Cambridge founded

- 1209 – foundation of the Franciscan Order

- 1209–1229 – Albigensian Crusade

- 1212 – Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa

- 1214 - Battle of Bouvines - Medieval France is a rising power

- 1215 – Magna Carta

- 1216 – recognition of the Dominican Order

- 1215 – Fourth Lateran Council

- 1217–1221 – Fifth Crusade

- 1218 – University of Salamanca founded

- 1220–1250 – Frederick II

- 1222 – University of Padua founded

- 1223 – approval of the FranciscanRule of Life

- 1228–1229 – Sixth Crusade

- 1230 – Prussian Crusade

- 1230 – Battle of Klokotnitsa

- 1237–1242 – Mongol invasion of Europe

- 1241 – Battle of Legnica and Battle of Mohi

- 1242 – Battle of the Ice

- 1248–1254 – Seventh Crusade

- 1257 – foundation of the Collège de Sorbonne

- 1261 – the Byzantine Empire reconquers Constantinople.

- 1274 – death of Thomas Aquinas; Summa Theologica published

- 1277-1280 – Uprising of Ivaylo – Medieval Europe's only successful peasant uprising

- 1280 – death of Albertus Magnus

- 1291 – Mamluks under Khalil.

See also

Notes

- ^ John H. Mundy, Europe in the high Middle Ages, 1150-1309 (1973) online

- ^ Reitervölker im Frühmittelalter. Bodo, Anke et.al. Stuttgart 2008

- ISBN 9780511497209.

- ^

See for example:

Aberth, John (2013). "The early medieval woodland". An Environmental History of the Middle Ages: The Crucible of Nature. Abingdon: Routledge (published 2012). p. 87. ISBN 9780415779456. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

The French historian of the early medieval forest, Charles Higounet, produced a map in the 1960s, which has been much reproduced since, that purports to show the distribution of the forest cover in Europe on the eve of the so-called 'great clearances' (les grands défrichements) between 1000 and 1300.

- ^ Taylor 2005, p. 181.

- ^ Adamson 2016, p. 180.

- ^ Fakhry 2001, p. 3.

- ^ Davies, Rees (2001-05-01). "Wales: A Culture Preserved". bbc.co.uk/history. p. 3. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Clemente Ramos 2018, p. 171.

- hdl:10459.1/58852.

- ^ Clemente Ramos 2018, p. 178.

- ^ Clemente Ramos 2018, p. 179.

- ^ Clemente Ramos 2018, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Clemente Ramos 2018, pp. 187.

- S2CID 165549625.

- ^ Clemente Ramos 2018, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Clemente Ramos 2018, p. 183.

- ^ "Trade in Medieval Europe". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- ^ Jellinek, E. M. 1976. "Drinkers and Alcoholics in Ancient Rome." Edited by Carole D. Yawney andRobert E. Popham. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 37 (11): 1718–1740.

- ISBN 9780674063693.

- ^ Franklin, J., "The Renaissance myth", Quadrant 26 (11) (Nov, 1982), 51-60. (Retrieved on-line at 06-07-2007)

- ^ A History of English literature for Students, by Robert Huntington Fletcher, 1916: pp. 85–88

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 86)

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 96)

Works cited

- ISBN 978-0-19-957749-1.

- Fakhry, Majid (2001), Averroes (Ibn Rushd) His Life, Works and Influence, ISBN 978-1-85168-269-0

- Taylor, Richard C. (2005). "Averroes: religious dialectic and Aristotelian philosophical thought". In Peter Adamson; Richard C. Taylor (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 180–200. ISBN 978-0-521-52069-0.

Further reading

- Fuhrmann, Horst. Germany in the High Middle Ages: c. 1050–1200 (Cambridge UP, 1986).

- Jordan, William C. Europe in the High Middle Ages (2nd ed. Penguin, 2004).

- Mundy, John H. Europe in the High Middle Ages, 1150–1309 (2014) – online

- Power, Daniel, ed. The Central Middle Ages: Europe 950–1320 (Oxford UP, 2006).

External links

- Music of the Middle Ages: 475–1500

- Middle Ages: The High Middle Ages in the Columbia Encyclopedia at Infoplease

- Provençal literature in the Columbia Encyclopedia at Infoplease