Hiking

Hiking is a long, vigorous

"Hiking" is the preferred term in

Related terms

In the United States, Canada, the Republic of Ireland, and the United Kingdom, hiking means walking outdoors on a trail, or off trail, for recreational purposes.

Hiking sometimes involves bushwhacking and is sometimes referred to as such. This specifically refers to difficult walking through dense forest, undergrowth, or bushes where forward progress requires pushing vegetation aside. In extreme cases of bushwhacking, where the vegetation is so dense that human passage is impeded, a

History

The poet Petrarch is frequently mentioned as an early example of someone hiking. Petrarch recounts that on April 26, 1336, with his brother and two servants, he climbed to the top of Mont Ventoux (1,912 meters (6,273 ft), a feat which he undertook for recreation rather than necessity.[10] The exploit is described in a celebrated letter addressed to his friend and confessor, the monk Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro, composed some time after the fact. However, some have suggested that Petrarch's climb was fictional.[11][12]

Other early examples of individuals hiking or climbing mountains for pleasure include the Roman Emperor, Hadrian, who ascended Mount Etna during a return trip from Greece in 125 CE. In 1275, Peter III of Aragon claimed to have reached the summit of Pic du Canigou, a 9134-foot mountain located near the southern tip of France. The first ascent of any technical difficulty to be officially verified took place on June 26, 1492, when Antoine de Ville, a chamberlain and military engineer for Charles VIII, King of France, was ordered to ascend Mont Aiguille. Because ropes, ladders and iron hooks were used during the ascent, this event is widely recognized as being the birth of mountaineering. Conrad Gessner, a 16th Century physician, botanist and naturalist from Switzerland, is widely recognized as being the first person to hike and climb for sheer pleasure.[20]

However, the idea of taking a walk in the countryside only really developed during the 18th century in Europe, and arose because of changing attitudes to the landscape and nature associated with the Romantic movement.[21] In earlier times walking generally indicated poverty and was also associated with vagrancy.[22]: 83, 297 In previous centuries long walks were undertaken as part of religious pilgrimages and this tradition continues throughout the world.

German-speaking world

The Swiss scientist and poet Albrecht von Haller's poem Die Alpen (1732) is an historically important early sign of an awakening appreciation of the mountains, though it is chiefly designed to contrast the simple and idyllic life of the inhabitants of the Alps with the corrupt and decadent existence of the dwellers in the plains.[23]

Numerous travellers explored Europe on foot in the last third of the 18th century and recorded their experiences. A significant example is Johann Gottfried Seume, who set out on foot from Leipzig to Sicily in 1801, and returned to Leipzig via Paris after nine months.[24]

United Kingdom

Thomas West, a Scottish priest, popularized the idea of walking for pleasure in his guide to the Lake District of 1778. In the introduction he wrote that he aimed

to encourage the taste of visiting the lakes by furnishing the traveller with a Guide; and for that purpose, the writer has here collected and laid before him, all the select stations and points of view, noticed by those authors who have last made the tour of the lakes, verified by his own repeated observations.[25]

To this end he included various 'stations' or viewpoints around the lakes, from which tourists would be encouraged to enjoy the views in terms of their aesthetic qualities.[26] Published in 1778 the book was a major success.[27]

Another famous early exponent of walking for pleasure was the English poet

More and more people undertook walking tours through the 19th century, of which the most famous is probably

Due to

Access to Mountains

The effort to improve access led after World War II to the

United States

An early example of an interest in hiking in the United States is

Despite clubs such as the Appalachian Mountain Club, hiking during the early twentieth century was still primarily in New England, San Francisco, and the Pacific Northwest. Eventually, there were similar clubs formed in the Midwest and following the Appalachian range. As interest grew hiking culture was spread throughout the nation.[1]

The Scottish-born, American naturalist

In 1921,

Pilgrimages

The ancient pilgrimage, the

The French Way is the most popular of the routes and runs from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port on the French side of the Pyrenees to Roncesvalles on the Spanish side and then another 780 kilometres (480 mi) on to Santiago de Compostela through the major cities of Pamplona, Logroño, Burgos and León. A typical walk on the Camino francés takes at least four weeks, allowing for one or two rest days on the way. Some travel the Camino on bicycle or on horseback. Paths from the cities of Tours, Vézelay, and Le Puy-en-Velay meet at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port.[44] The French long-distance path GR 65 (of the Grande Randonnée network), is an important variant route of the old Christian pilgrimage way.

The

Destinations

Frequently, nowadays long-distance hikes (walking tours) are undertaken along long-distance paths, including the

In the late 20th-century, there has been a proliferation of official and unofficial long-distance routes, which mean that hikers now are more likely to refer to using a long-distance way (Britain), trail (US), The Grande Randonnée (France), etc., than setting out on a walking tour. Early examples of long-distance paths include the Appalachian Trail in the US and the Pennine Way in Britain.

Organized hiking clubs emerged in Europe at approximately the same time as official hiking trails. These clubs established and upheld their own paths during the 19th and 20th centuries, prioritizing the development of extended hiking routes. In 1938, the first long-distance hiking trail in Europe, the Hungarian National Blue Trail, was established in the Hungarian wilderness, stretching approximately 62 miles (100 km).

Asia

In the Middle East, the Jordan Trail is a 650 km (400 miles) long hiking trail in Jordan established in 2015 by the Jordan Trail Association. And Israel has been described as "a trekker's paradise" with over 9,656 km (6,000 miles) of trails.[46]

The Lycian Way is a marked long-distance trail in southwestern Turkey around part of the coast of ancient Lycia.[47] It is over 500 km (310 mi) in length and stretches from Hisarönü (Ovacık), near Fethiye, to Geyikbayırı in Konyaaltı about 20 km (12 mi) from Antalya. It was conceived by Briton Kate Clow, who lives in Turkey. It takes its name from the ancient civilization, which once ruled the area.[48]

The Great Himalaya Trail is a route across the Himalayas. The original concept of the trail was to establish a single long distance trekking trail from the east end to the west end of Nepal that includes a total of roughly 1,700 kilometres (1,100 mi) of path. The proposed trail will link together a range of the less explored tourism destinations of Nepal's mountain region.[49]

Latin America

In Latin America, Peru and Chile are important hiking destinations. The Inca Trail to Machu Picchu in Peru is very popular and a permit is required. The longest hiking trail in Chile is the informal 3,000 km (1,850 mi) Greater Patagonia Trail that was created by a non-governmental initiative.[50]

Africa

In Africa a major

Equipment

The equipment required for hiking depends on a variety of factors, including local climate. Day hikers often carry water, food, a map, hat, and rain-proof gear.

Proponents of ultralight backpacking argue that long lists of required items for multi-day hikes increases pack weight, and hence fatigue and the chance of injury.[57] Instead, they recommend reducing pack weight, to make hiking long distances easier. Even the use of hiking boots on long-distances hikes is controversial among ultralight hikers, because of their weight.[57]

Hiking times can be estimated by Naismith's rule or Tobler's hiking function, while distances can be measured on a map with an opisometer. A pedometer is a device that records the distance walked.

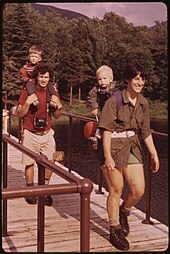

Hiking with children

The American Hiking Society advises that parents with young children should encourage them to participate in decision-making about route-finding and pace.[58] Alisha McDarris, writing in Popular Science, suggests that, whilst hiking with children poses particular challenges, it can be a rewarding experience for them, particularly if a route is chosen with their interests in mind.[59]

Young children are prone to becoming fatigued more rapidly than adults, requiring fluids and energy-rich foods more frequently, and are also more sensitive to variations in weather and terrain. Hiking routes may be chosen with these factors in mind, and appropriate clothing, equipment and sun-protection need to be available.[60][61]

Environmental impact

Fire is a particular source of danger, and an individual hiker can have a large impact on an ecosystem. For example, in 2005, a Czech backpacker accidentally started a fire that burnt 5% of Torres del Paine National Park in Chile.[64]

Etiquette

Because hikers may come into conflict with other users of the land or may harm the natural environment, hiking etiquette has developed.

- When two groups of hikers meet on a steep trail, a custom has developed in some areas whereby the group moving uphill has the right-of-way.[65]

- Various organizations recommend that hikers generally avoid making loud sounds, such as shouting or loud conversation, playing music, or the use of mobile phones.[65] However, in bear country, hikers use intentional noise-making as a safety precaution to avoid startling bears.

- The Leave No Trace movement offers a set of guidelines for low-impact hiking: "Leave nothing but footprints. Take nothing but photos. Kill nothing but time. Keep nothing but memories".[66]

- Hikers are advised not to feed wild animals, because they will become a danger to other hikers if they become habituated to human food, and may have to be killed, or relocated.[67]

Hazards

Hiking can be hazardous because of terrain, inclement weather, becoming lost, or pre-existing medical conditions. The dangerous[68] circumstances hikers can face include specific accidents or physical ailments. It is especially hazardous in high mountains, crossing rivers and glaciers, and when there is snow and ice. At times hiking may involve scrambling, as well as the use of ropes, ice axes and crampons and the skill to properly use them.

Potential hazards involving physical ailments may include dehydration, frostbite, hypothermia, sunburn, sunstroke, or

Other threats include attacks by animals (e.g., bears, snakes, and

Walkers in high mountains, and during winter in many countries, can encounter hazardous snow and ice conditions, and the possibility of avalanches.[73] Year round glaciers are potentially hazardous.[74] Fast flowing water presents another danger and a safe crossing may requires special techniques.[75]

In various countries, borders may be poorly marked. In 2009, Iran imprisoned three Americans for hiking across the Iran-Iraq border.

Winter hiking

Hiking in winter offers additional opportunities, challenges and hazards.

See also

Types

- Backpacking (hiking). And, in winter, Ski touring

- Dog hiking– hiking where a dog carries a pack

- Fastpacking – fast hiking with light gear

- Glacier hiking – hiking on a glacier that has affinities to mountaineering

- Llama hiking – hiking where llamas accompany people

- trekking poles

- Swimhiking – a sport that combines hiking and swimming

- Ultralight backpacking – carrying the least amount of gear necessary

- Waterfalling – hiking that explores waterfalls

Related activities

- Cross-country skiing – hiking snow with the aid of skis

- Fell running – the sport of running over rough mountainous ground, often off-trail

- Geocaching – an outdoor treasure-hunting game

- Orienteering – a sport that involves navigation with a map and compass

- Peak bagging – ticking-off a list of mountain peaks climbed

- Pilgrimage – a journey of moral or spiritual significance

- River trekking – a combination of trekking and climbing and sometimes swimming along a river

- Rogaining – a sport of long-distance cross-country navigation

- Snow shoeing– walking across deep snow on snow shoes

- Thru-hiking – hiking an established long-distance hiking trail continuously in one direction

- Trail blazing – using signages to mark a hiking route (known as way-marking in Europe)

- Trail running – running on trails

References

- ^ JSTOR j.ctt9qg056. Archivedfrom the original on 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2020-11-25.

- ^ "Sydney Bush Walkers Club's history". Archived from the original on 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2017-02-21.

- ISBN 0-19-558347-7.

- ^ McKinney, John (2009-03-22). "For Good Health: Take a Hike!". Miller-McCune. Archived from the original on 2011-04-29.

- ^ "A Step in the Right Direction: The health benefits of hiking and trails" (PDF). American Hiking Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7368-0916-0.

- ^ "Bushwalking Australia home". Bushwalking Australia. Archived from the original on 2016-03-22. Retrieved 2016-03-18.

- ISBN 9780195583472.

- ISBN 0-07-044458-7.

- OCLC 1031245016.

- JSTOR 2707236.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (August 1998). "Petrarch: The Ascent of Mount Ventoux". fordham.edu. Fordham University. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "Civilization, Part IV §3, beginning". Archived from the original on February 3, 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-226-09604-9.

- ^ Bishop, p.102,104

- ^ link to a collection of several letters in the same issue.

- ^ Moody, Ernest A. "Jean Buridan" (PDF). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-13. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- from the original on 2023-01-02. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- Swan Sonnenschein. pp. 301–302.

- ^ ISBN 979-8373963923.

- ISBN 9780393963380.

- ISBN 0670882097.

- ^ Chisholm 1911, p. 855.

- )

- ISBN 9780371947258.

- ^ "Development of tourism in the Lake District National Park". Lake District UK. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- ^ "Understanding the National Park — Viewing Stations". Lake District National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 2008-11-27.

- ISBN 9780719028915. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ISBN 978-0-7190-2966-0.

- ^ "Quarrying and mineral extraction in the Peak District National Park" (PDF). Peak District National Park Authority. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ "Kinder Trespass. A history of rambling". Archived from the original on 2012-07-08. Retrieved 2013-12-17.

- ^ "Open access land: management, rights and responsibilities". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 2021-03-10. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000". legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2023-04-24. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ Condensed Facts About Mount Washington. Atkinson News Co. 1912.

- ^ Thoreau, Henry David. "Walking". The Atlantic. No. June 1862. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- ^ "Lynn Woods Historic District". NPS. 7 July 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "The Life and Contributions of John Muir". Sierra Club. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- ISBN 978-0836883183.

- ^ "Quick History of the National Park Service (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-03-09. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "National Park Service". HISTORY. 21 August 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-03-05. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "Congress Creates the National Park Service". National Archives. 2016-08-25. Archived from the original on 2021-03-26. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "The Top 10 Hiking Trails in the US". e2e.com. Archived from the original on 2014-02-23. Retrieved 2014-02-12.

- ^ "North Downs Way National Trail | Paths by name | Ramblers, Britain's Walking Charity". 2012-07-28. Archived from the original on 2012-07-28. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ Starkie, Walter (1965) [1957]. The Roads to Santiago: Pilgrims of St. James. University of California Press.

- ^ "Abraham Path | a cultural route connecting the storied places associated with Abraham's ancient journey". abrahampath.org. Archived from the original on 2017-05-17. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- ^ "Hiking in Israel – a trekkers paradise". 2012-08-15. Archived from the original on 2014-05-25.

- ^ "Lycian Way". Culture Routes Society. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Whitman Piper, Ernest (8 July 2017). "Lycian Way: Hike through the best trekking route in Turkey". Daily Sabah. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Great Himalaya Trails :: Trekking, hiking and walking in Nepal". Great Himalaya Trails. Archived from the original on 2020-11-16. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ^ Dudeck, Jan. "Greater Patagonian Trail". Wikiexplora. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Trimble, Morgan (2016-11-15). "How to climb Kilimanjaro without the crowds". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2023-01-02. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ Sharaf, Yasir (24 March 2016). "Mount Kilimanjaro Volcanic Cones: Shira, Kibo And Mawenzi Peaks". XPATS International. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ O'Grady, Kyle (4 December 2015). "The Footwear Debate: Are Trail Runners Superior to Boots?". The Trek. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ISBN 0-89886-427-5.

- ^ "Ten Essential Groups Article". Texas Sierra Club. Archived from the original on 2011-06-02. Retrieved 2011-01-19.

- ^ "Trekking Poles". American Hiking Association. 10 April 2013. Archived from the original on 2020-11-13. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- ^ ISBN 0963235931.

- ^ Ray, Tyler (2013-04-10). "Hiking with Kids". American Hiking Society. Archived from the original on 2023-02-03. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ McDarris, Alisha (2020-05-19). "What you need to know when hiking with kids". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 2022-11-27. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ "Wandern mit Kindern". www.alpenverein.at (in German). Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Bloch, Romana (Sep 2017). "Bergtouren mit Kindern: Das muss man beachten!" [Mountain tours with children: You have to pay attention to this!]. Alpin (in German). Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Cole, David. "Impacts of Hiking and Camping on Soils and Vegetation: A Review" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "About Our Mission". Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics. Archived from the original on 2020-09-16. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- ^ "Chile and Czech Republic work to restore Torres del Paine Park". MercoPress. 2009-09-30. Archived from the original on 2020-06-17. Retrieved 2020-06-17.

- ^ ISSN 0277-867X. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ "Leave No Trace Seven Principles (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2021-03-18.

- ^ "Do Not Feed Wildlife". Upper Thames River Conservation Authority. Archived from the original on 2023-01-02. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ^ "Is Hiking Dangerous?". Trekkearth. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- PMID 12681456.

- ISBN 978-0-7360-6801-7.

- ^ a b "Altitude Diseases – Injuries; Poisoning". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. May 2018. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- PMID 29959871.

- ^ "Avalanche danger". Pacific Crest Trails Association. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- ^ "How to cross a glacier". Washington Trails Association. Archived from the original on 2021-05-12. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- ^ "Stream crossing safety while hiking and backpacking". Pacific Crest Trail Association. Archived from the original on 2020-11-08. Retrieved 2020-11-12.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R.; Lehren, Andrew W. (2010-10-23). "Iran Seized U.S. Hikers in Iraq, U.S. Report Asserts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-04-24. Retrieved 2017-02-24.

- ^ "Hiking the Via Alpina – Questions / Answers". www.via-alpina.org. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Winter Hiking: What to Know Before You Go". Appalachian Trail Conservancy. 2019-01-21. Archived from the original on 2023-01-31. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- ISBN 978-1-59485-038-7. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- ^ "Transport in, to and out of the backcountry – Snow Safety information". mountainacademy.salomon.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Ten mistakes winter walkers make – and how to avoid them". www.thebmc.co.uk. British Mountaineering Council. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Hill skills: avalanche awareness". www.thebmc.co.uk. British Mountaineering Council. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

Bibliography

- Amata, Joseph (2004). On Foot, A History of Walking. New York: New York University Press.

- ISBN 978-0-847-86093-7.

- Chamberlin, Silas (2016). On the Trail : A History of American Hiking. Yale University Press.

- Doran, Jeffrey J. (2023). Ramble On: How Hiking Became One of the Most Popular Outdoor Activities in the World. Amazon Digital Services LLC – Kdp. ISBN 979-8373963923.

- Gros, Frédéric (2014). A Philosophy of Walking. Translated by Howe, John. London, New York: Verso. ISBN 9781781682708.

- Solnit, Rebecca (2000). Wanderlust: a history of walking. New York: Viking.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Haller, Albrecht von". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Recreation: Outdoors: Hiking at Curlie