Hispanic Americans in World War II

On December 7, 1941, when the United States officially entered the war, Hispanic Americans were among the many American citizens who entered the ranks of the

As conscription numbers increased, some

Terminology

Prelude to World War II

Before the United States entered World War II, Hispanic Americans were already fighting on European soil in the

General Manuel Goded Llopis (1882–1936), who was born in San Juan, Puerto Rico, was a high-ranking officer in the Spanish Army. Llopis was among the first generals to join Franco in the uprising against the government of the Second Spanish Republic. Llopis led the fight against the Anarchists in Catalonia, but his troops were outnumbered. He was captured and sentenced to die by firing squad.[11][12]

Pearl Harbor

On December 7, 1941, when the Empire of Japan attacked the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, many sailors with Hispanic surnames were among those who perished.[14] PFC Richard I. Trujillo of the United States Marine Corps was serving aboard the battleship USS Nevada (BB-36) when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. The Nevada was among the ships which were in the harbor that day. As her gunners opened fire and her engineers got up steam, she was struck by torpedoes and bombs from the Japanese attackers. Fifty men were killed and 109 wounded. Among those killed was Trujillo, who became the first Hispanic Marine casualty of World War II.[15]

When the United States officially entered World War II, Hispanic Americans were among the many American citizens who joined the ranks of United States Armed Forces as volunteers or through the

In 1941, Commander Luis de Florez played an instrumental role in the establishment of the Special Devices Division of the Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics (what would later become the

European Theater

The

Hispanics of the 141st Regiment of the 36th Infantry Division were some of the first American troops to

65th Infantry Regiment

A small detachment of insular troops from Puerto Rico was sent to Cuba in late March as a guard for Batista Field. In 1943, the 65th Infantry was sent to Panama to protect the Pacific and the Atlantic sides of the isthmus and the Panama Canal, critical to oceangoing ships. An increase in the Puerto Rican induction program was immediately authorized. Continental troops such as the 762nd Antiaircraft Artillery Gun Battalion, 766th AAA Gun Battalion and the 891st AAA Gun Battalions were replaced by Puerto Ricans in Panama.[20][21] They also replaced troops in the bases on British Islands, to the extent permitted by the availability of trained Puerto Rican units.[4] The 295th Infantry Regiment followed the 65th Infantry in 1944, departing from San Juan, Puerto Rico to the Panama Canal Zone.

That same year, the 65th Infantry was sent to North Africa, where they underwent further training. By April 29, 1944, the regiment had

The 3rd Battalion fought against and defeated the German 107th Infantry Regiment, which was assigned to the 34th Infantry Division.

In March 1943, Private First Class Joseph (Jose) R. Martinez, a member of General George S. Patton's Seventh Army, destroyed a German infantry unit and tank in Tunis by directing heavy artillery fire, saving his platoon from being attacked in the process. He received the Distinguished Service Cross, second to the Medal of Honor.[26]

Sergeant First Class Agustín Ramos Calero, a member of the 65th Infantry who was reassigned to the 3rd U.S. Infantry Division because of his ability to speak and understand English, was one of the most decorated Hispanic soldiers in the European Theater.[24] Calero was born and raised in Isabela, in the northern region of Puerto Rico. He joined the U.S. Army in 1941 and was assigned to Puerto Rico's 65th Infantry Regiment at Camp Las Casas in Santurce, where he received training as a rifleman. Calero was later reassigned to the 3rd U.S. Infantry Division and later sent to Europe.

In 1945, Calero's company engaged in combat against a squad of German soldiers in the

Pacific Theater

and Brigadier General del Valle, Corps Artillery Commander, examine a plaster relief map of Guam on board USS Appalachian.

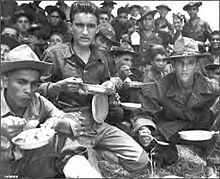

Three units of mostly Hispanic Americans served in the

Bataan Death March

Two

By April 9, 1942, rations, medical supplies, and ammunition became scarce and the decision was made to surrender. The 200th and 515th Battalions were part of the forces surrendering to the Japanese.

Colonel Virgilio N. Cordero Jr. (1893–1980) was a battalion commander in the 31st Infantry Regiment on December 8, 1941, when Japanese planes attacked the U.S. military installations in the Philippines.[31] Cordero and his men underwent brutal torture and humiliation during the Bataan Death March and nearly four years of captivity. Cordero was one of nearly 1,600 members of the 31st Infantry who were taken as prisoners. Half of these men perished while prisoners of the Japanese forces. Cordero was freed when Allied troops defeated the Japanese and he returned to the United States.[31] Cordero, who retired with the rank of brigadier general,[31] wrote about his experiences as a prisoner of war and what he went through during the Bataan Death March. The book, titled My Experiences during the War with Japan, was published in 1950. In 1957, he authored a revised Spanish version titled Bataan y la Marcha de la Muerte; Volume 7 of Colección Vida e Historia.[31]

Private (Pvt.) Ralph Rodriguez, age 25, of the 200th Coast Artillery Battalion was a Bataan Death March survivor. According to Rodriguez, the Japanese ordered the American soldiers to begin marching. Soldiers who faltered during the march were prodded with bayonets, while those unable to continue were killed. He remembered a sense of brotherhood among the Hispanic soldiers who marched together in groups, and assisted each other along the way. When the soldiers reached their detention center, they were forced into a 30-by-100 foot fenced area. Later, the soldiers were housed in boxcars. One hundred soldiers were crammed into a car built to hold 40 or 50 men. The train took the soldiers on a four-hour ride to Camp O'Donnell where they became prisoners of war.[32]

Corporal Agapito E. "Gap" Silva (1919–2007), was another member of the 200th Coast Artillery Battalion who survived the Bataan Death March. He was held at

"The POWs (prisoner of war) faced constant danger working in the coal mines. It was so unbearable that many of the men would resort to self-inflicted injuries such as breaking their arms and legs to avoid working 10 to 12 hour days."[34]

Silva and more than 1,900 American POWs were forced to work in coal mine camps encircled by electric fences. Silva would spend 3½ years in the Japanese POW camps before the war ended in September 1945.[citation needed] He was the recipient of the Bronze Star and Purple Heart Medal.[33]

158th Infantry Regiment

The 158th Infantry Regiment, an

PFC Guy Gabaldon

PFC Guy Gabaldon (1926–2006) was raised in East Los Angeles where he grew up around people of all races, including Japanese-Americans. Through those friendships, he was able to teach himself to speak Japanese. Gabaldon joined the Marines when he was only 17 years old; he was a Private First Class (PFC) when his unit was engaged in the Battle of Saipan in 1944. Gabaldon, who acted as the Japanese interpreter for the Second Marines, working alone in front of the lines, entered enemy caves, pillboxes, buildings, and jungle brush, frequently in the face of hostile fire, and succeeded not only in obtaining vital military information,[citation needed] but in convincing over 1,500 enemy civilians and troops to surrender. He was nominated for the Medal of Honor, but was awarded the Silver Star instead. His medal was later upgraded to the Navy Cross, the Marines' second-highest decoration for heroism.[citation needed] Gabaldon's actions on Saipan were later memorialized in the film Hell to Eternity, in which he was portrayed by actor Jeffrey Hunter.[38]

Guarding the atomic bomb

In 1945, when Kwajalein of the

United States Coast Guard

Many Hispanics also served in the United States Coast Guard. Joseph B. Aviles Sr. was the first Hispanic to be promoted to chief petty officer in the Coast Guard after transferring from the Navy in 1925. During the war he was also the first Hispanic to be promoted to chief warrant officer.

Valentin R. Fernandez was awarded a Silver Lifesaving Medal for "maneuvering a Marine landing party ashore under constant Japanese attack" during the invasion of Saipan.

Louis Rua was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for "meritorious achievement at sea December 5–6, 1944, while serving aboard a U.S. Army large tug en route to the Philippines. His craft went to the rescue of another ship which had been torpedoed by enemy action and saved 277 survivors from the abandoned ship." He was the first known Hispanic-American Coast Guardsman to be awarded the Bronze Star Medal.

Gunner's Mate Second Class Joseph Tezanos was awarded a Navy & Marine Corps Medal during World War II for "...distinguished heroism while serving as a volunteer member of a boat crew engaged in rescue operations during a fire in Pearl Harbor, Oahu, T.H. on 21 May 1944. Under conditions of great personal danger from fire and explosions and with disregard of his own safety he assisted in the rescuing of approximately 42 survivors some of whom were injured and exhausted from the water and from burning ships." He was also the second known Hispanic-American to complete OCS training at the Coast Guard Academy.[39]

Not everyone served aboard ships during the war. Some men like Jose R. Zaragoza served on atolls or other shore locations. When 19-year-old Zaragoza, a native of Los Angeles, California, joined the Coast Guard, he was sent on patrols in the Pacific coast of the United States defending against sabotage and invasion from the Japanese. He then trained in the new and classified field of

Aviators

Hispanics not only served in ground and seabound combat units, they also distinguished themselves as

A "

First Lieutenant Perdomo, (1919–1976), the son of Mexican parents, was born in

On August 13, 1945, 1st Lt. Perdomo shot down four

Not all Hispanics who served in aviation units were pilots or aces. Examples ranging from aces to air crew members show the diversity of their experiences in the air war.

- Commander Eugene A. Valencia Jr., United States Navy (USN) fighter ace, is credited with 23 air victories in the Pacific during World War II. Valencia's decorations include the Navy Cross, six Distinguished Flying Crosses, and six Air Medals.[45]

- Lieutenant Colonel Donald S. Lopez Sr., USAAF pilot credited with shooting down five Japanese fighters in the China theater. He eventually became the deputy director of the National Air and Space Museum[46]

- Captain Michael Brezas, USAAF fighter ace, arrived in P-38 aircraft, Lt. Brezas downed 12 enemy planes within two months. He received the Silver Star Medal, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Air Medal with eleven oak leaf clusters.[47]

- Captain Mihiel "Mike" Gilormini, Royal Air Force and USAAF, was a flight commander whose last combat mission was attacking the airfield at Milano, Italy. His last flight in Italy gave air cover for General George C. Marshall's visit to Pisa. Gilormini was the recipient of the Silver Star Medal, five Distinguished Flying Crosses, and the Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters. Gilormini later founded the Puerto Rico Air National Guard and retired as brigadier general.[48]

- Captain P-51 Mustang fighter pilot. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with four oak leaf clusters and the Air Medal with four oak leaf clusters. Nido co-founded the Puerto Rico Air National Guard and, as Gilormini, retired a brigadier general.[49]

- Captain Robert L. Cardenas, USAAF, served as a B-29 launch aircraft that released the X-1 experimental rocket plane in which Chuck Yeager became the first man to fly faster than the speed of sound. Cardenas retired as a brigadier general.[50]

- 2nd Lieutenant Distinguished Unit Citation for carrying out this second mission in spite of bad weather and heavy fire from enemy ground and naval forces. González died on November 22, 1943, when his plane crashed during training off the end of the runway at Castelvetrano. He was posthumously promoted to first lieutenant.[51]

- Lieutenant Richard Gomez Candelaria, USAAF, was a P-51 Mustang pilot from the 479th Fighter Group. With six aerial victories to his credit, Candelaria was the only "ace" in his squadron. Most of his victories were achieved on a single mission on April 7, 1945, when he found himself the lone escort protecting a formation of USAAF B-24 Liberators. Candelaria defended the bombers from at least 15 German fighters, single-handedly destroying four before help arrived. He was also credited with a probable victory on an Me 262 during this engagement. Six days later, Candelaria was shot down by ground fire, and spent the rest of the war as a POW. After the war, Candelaria served in the Air National Guard, reaching the rank of colonel prior to his retirement.[52]

- Lieutenant F-86s celebrating the 4th of July Puerto Rico. During take-off his engine flamed out and crashed. In 1963, the Air National Guard Base, at the San Juan International airport in Puerto Rico, was renamed "Muñiz Air National Guard Base" in his honor.[54]

- Lieutenant Marianas Turkey Shoot.[55] Additionally, Van Haren Jr. was awarded two Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) medals.[56]

- Technical Sergeant Clement Resto, USAAF, served with the 303rd Bomb Group and participated in numerous bombing raids over Germany. During a bombing mission over Duren, Germany, Resto's plane, a B-17, was shot down. He was captured by the Gestapo and sent to Stalag XVII-B where he spent the rest of the war as a prisoner of war. Resto, who lost an eye during his last mission, was awarded a Purple Heart, a POW Medal and an Air Medal with one battle star after he was liberated from captivity.[57][58]

- Corporal Frank Medina, USAAF, was an air crew member on a B-24 that was shot down over Italy. He was the only one to evade capture. Medina said his ability to speak Spanish had allowed him to communicate with friendly Italians who helped him avoid capture for eight months behind enemy lines.[59]

Servicewomen

Prior to World War II, traditional Hispanic cultural values expected women to be homemakers and they rarely left the home to earn an income. This outlook discouraged women from joining the military. Only a small number of Hispanic women had joined before World War II.

In 1944, the Army recruited women in Puerto Rico for a segregated Hispanic unit in the Women's Army Corps (WAC). Over 1,000 applications were received for the unit, which was to be composed of 200 women. After their basic training at

One of the members of the 149th WAAC Post Headquarters Company was Tech4

Contreras' unit arrived in North Africa on January 27, 1943, experiencing nightly

Mercedes O. Cubria, born in Guantanamo, Cuba, became a United States Citizen in 1924. She joined the WAC in 1943 and served in U.S. Counter-Intelligence. She retired in 1973 with the rank of lieutenant colonel.[66]

Other

Nurse Corps

When the United States entered World War II, the military needed nurses. Hispanic female nurses wanted to volunteer for service but they were not immediately accepted into the

Second Lieutenant Carmen Lozano Dumler was born and raised in San Juan, Puerto Rico, where she also received her primary and secondary education. After graduating from high school, she enrolled in the Presbyterian Hospital School of Nursing in San Juan where she became a certified nurse in 1944. On August 21, 1944, she was sworn in as a second lieutenant and assigned to the 161st General Hospital in San Juan, where she received further training. Upon completing her advanced training, she was sent to Camp Tortuguero where she also assisted as an interpreter.

In 1945, Lozano Dumler was reassigned to the 359th Station Hospital of Ft. Read, Trinidad and Tobago, British West Indies, where she attended wounded soldiers who had returned from Normandy, France. After the war, Lozano, like so many other women in the military, returned to civilian life. She continued her nursing career in Puerto Rico until she retired in 1975.[67]

Another Hispanic nurse who distinguished herself in service was Lieutenant Maria Roach. Roach, a recipient of two Bronze Star Medals and an Air Medal, served as a flight nurse with the Army Nurse Corps in the

Other notable cases

Another very particular case was carried out by Colombian sergeant Benjamín Quintero Martínez, who served in the Pacific War in the defense of the Aleutian Islands, holding the position of technical sergeant communications in the Pacific, Aleutian Islands, and Alaska.[68]

Senior officers

Most of the Hispanics serving as senior military officers during World War II were graduates of the

Generals

- Major General del Valle

Lieutenant General

On April 1, 1944, del Valle, as Commanding General of the Third Corps Artillery,

In late October 1944, del Valle succeeded Major General

- Brigadier General Quesada

Lieutenant General

In December 1942, Quesada took the First Air Defense Wing to North Africa. Shortly thereafter, he was given command of the XII Fighter Command and in this capacity would work out the mechanics of close air support and Army-Air Force cooperation.[70]

The successful integration of air and land forces in the

- Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen

Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. (1888–1969) was the son of Colonel Samuel Edward Allen and Conchita Alvarez de la Mesa. During World War II he was the commanding general of the 1st Infantry Division in North Africa and Sicily, and was made commander of the 104th Infantry Division. While in North Africa Allen and his deputy 1st Division Commander, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. distinguished themselves as combat leaders. Allen was reassigned to the 104th Infantry Division. The 104th Infantry Division landed in France on September 7, 1944, and fought for 195 consecutive days during World War II. The division's nickname came from its timberwolf shoulder insignia. Some 34,000 men served with the division under Allen, who came to be nicknamed "Terrible Terry". The division was particularly renowned for its night fighting prowess.[71]

Commanders

In 1941, Commander

A number of Hispanics served in senior leadership positions during World War II, including Admiral Horacio Rivero Jr. (USN), Rear Admiral Jose M. Cabanillas (USN), Rear Admiral Edmund Ernest García (USN), Rear Admiral Frederick Lois Riefkohl (USN), Rear Admiral Henry G. Sanchez (USN), Colonel Louis Gonzaga Mendez Jr. (USA), Colonel Virgil R. Miller (USA), Colonel Jaime Sabater Sr. (USMC) and Lieutenant Colonel Chester J. Salazar (USMC).

- Admiral Horacio Rivero Jr., USN, served aboard the cruiser USS San Juan, providing artillery cover for Marines landing on Guadalcanal, Marshall Islands, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. Rivero eventually reached the rank of Full-Admiral (four-stars) and in October 1962, found himself in the middle of the Cuban Missile Crisis. As Commander of amphibious forces, Atlantic Fleet, he was on the front line of the vessels sent to the Caribbean by President Kennedy to stop the Cold War from escalating into World War III.[72]

- Rear Admiral Edmund Ernest García, USN, was the commander of the destroyer USS Sloat and saw action in the invasions of Africa, Sicily, and France.[73]

- Rear Admiral Jose M. Cabanillas, USN, was an executive officer of the battleship USS Texas, which participated in the invasions of North Africa and Normandy (D-Day) during World War II. In 1945, he became the first commanding officer of USS Grundy.[74]

- Rear Admiral Ensign C. Kenneth Ruiz, who later become a submarine commander.[75]

- Rear Admiral Henry G. Sanchez, USN, commanded (as a Lieutenant Commander) VF-72, an F4F squadron of 37 aircraft, on board USS Hornet from July to October 1942. His squadron was responsible for shooting down 38 Japanese airplanes during his command tour, which included the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands.[76]

- Colonel Virgilio N. Cordero Jr., USA, was the Battalion Commander of the 31st Infantry Regiment in the Philippines. Survivor of the infamous Bataan Death March, he was awarded three Silver Star Medals and a Bronze Star Medal.

- Colonel 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment during World War II, parachuted behind enemy lines into Normandy and was awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for leading an attack that captured the French town of Prétot-Sainte-Suzanne, in the Manche (Basse-Normandie) department. On June 6, 2002, the people of the village honored his memory by renaming Prétot's main square "La Place du Colonel Mendez". He was also the recipient of 3 Bronze Star Medals.[77]

- Colonel 442d Regimental Combat Team, a unit which was composed of "Nisei" (second generation Americans of Japanese descent), during World War II. He led the 442nd in its rescue of the Lost Texas Battalion of the 36th Infantry Division, in the forests of the Vosges Mountains in northeastern France.[78][79]

- Colonel Jaime Sabater Sr., USMC, commanded the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines during the Bougainville amphibious operations of World War II.[80] Sabater also participated in the Battle of Guam (July 21 – August 10, 1944) as Executive officer of the 9th Marines. On July 21, 1944, he was wounded in action and awarded the Purple Heart.[81]

- Lieutenant Colonel Chester J. Salazar, USMC, was the commanding officer of the 2d Battalion, 18th Marines. Salazar served as commanding officer the unit in the Gilbert Islands which fought in the Battle of Tarawa and later in the Battles of Saipan and Tinian.[82]

Submarine commanders

Captain

After a brief stint at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard, he was reassigned to USS Skate, a Balao-class submarine. He participated in Skate's first three war patrols and was awarded a second Silver Star Medal for his contribution in sinking the Japanese light cruiser Agano on his third patrol. Agano had survived a previous torpedo attack by submarine USS Scamp.[84]

In April 1944, Ramirez de Arellano was named

Among the Hispanic submarine commanders were Rear Admiral Rafael Celestino Benítez and Captain C. Kenneth Ruiz.

Rear Admiral Rafael Celestino Benítez, USN, was a lieutenant commander who saw action aboard submarines and on various occasions weathered depth charge attacks. For his actions, he was awarded the Silver and Bronze Star Medals. Benitez would go on to play an important role in the first American undersea spy mission of the Cold War as commander of the submarine USS Cochino in what became known as the "Cochino Incident".[85]

Captain Charles Kenneth Ruiz, USN, was a crew member of the cruiser

Military honors

Recipients of the Medal of Honor

The

Prior to March 18, 2014, there were a total of 13 Hispanic Medal of Honor recipients awarded for their actions in World War II. On February 21, 2014, President Barack Obama announced that on March 18 that year, 4 Hispanics who served in World War II would have their Distinguished Service Cross Medals upgraded to the Medal of Honor in a ceremony at the White House. They are: Pvt. Pedro Cano, Pvt. Joe Gandara, Pfc. Salvador J. Lara and Staff Sgt. Manuel V. Mendoza. The award came through the Defense Authorization Act which called for a review of Jewish American and Hispanic American veterans from World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War to ensure that no prejudice was shown to those deserving the Medal of Honor.[88][89]

Of the 17 Medals of Honor awarded to Hispanics, ten were awarded posthumously. Texas accounted for the most Hispanic Medal of Honor recipients in World War II with a total of five (Marcario Garcia was raised in Sugar Land, Texas). The 17 recipients are:

- Lucian Adams: United States Army. Born in Port Arthur, Texas. Place and Date of Action: St. Die, France, October 1944.[90]

- Pedro Cano*: United States Army. Born in La Morita, Mexico. For courageous actions during combat operations in Schevenhutte, Germany, on Dec. 3, 1944.[88]

- Filipino ancestry to receive the medal for his actions in the war in Europe.[91]

- Joe Gandara*: United States Army. Born in Santa Monica, California. For courageous actions during combat operations in Amfreville, France, on June 9, 1944.[88]

- Marcario Garcia: United States Army. Born in Villa de Castano, Mexico. Place and Date of Action: Near Grosshau, Germany, November 27, 1944. Garcia was the first Mexican national Medal of Honor recipient.[92]

- Harold Gonsalves*: United States Marine Corps. Born in Alameda, California. Place and Date of Action: Ryūkyū Chain, Okinawa, April 15, 1945.[92]

- Pacoima, California. Place and Date of Action: Villa Verde Trail, Luzon, Philippine Islands, April 25, 1945.[92]

- Silvestre S. Herrera: United States Army. Born in Camargo, Chihuahua, Mexico. Place and Date of Action: Near Mertzwiller, France, March 15, 1945. At the time of his death, Herrera had been the only living person authorized to wear the Medal of Honor and Mexico's equivalent Premier Merito Militar (Order of Military Merit), Mexico's highest award for valor. Herrera was a Mexican citizen by birth.[92][93]

- Salvador J. Lara*: United States Army. From Riverside, California. For courageous actions during combat operations in Aprilia, Italy, May 27–28, 1944.[88]

- Joe P. Martinez*: United States Army. Born in Taos, New Mexico. Place and Date of Action: Attu, Aleutians, May 26, 1943. Martinez was the first Hispanic American posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for combat heroism on American soil during World War II.[94]

- Manuel V. Mendoza*: United States Army. Born in Miami, Arizona. For courageous actions during combat operations on Mount Battaglia, Italy, on Oct. 4, 1944.[88]

- Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Place and Date of Action: Fort William McKinley, Luzon, Philippine Islands, February 13, 1945.[94]

- Cleto L. Rodriguez: United States Army. Born in San Marcos, Texas. Place and Date of Action: Paco Railroad Station, Manila, Philippine Islands, February 9, 1945.[94]

- Alejandro R. Ruiz: United States Army. Born in Loving, New Mexico. Place and Date of Action: Okinawa, Japan, April 28, 1945.[94]

- Jose F. Valdez*: United States Army. Born in Governador, New Mexico. Place and Date of Action: Rosenkrantz, France, January 25, 1945.[95]

- Ysmael R. Villegas*: United States Army. Born in Casa Blanca, California. Place and Date of Action: Villa Verde Trail, Luzon, Philippine Islands, March 20, 1945.[95]

* Awarded

Additional decorations

| Hispanic Americans: U.S. Armed Forces Awards in World War II |

Number |

| 17 | |

| 140 | |

| 25 | |

| 323 | |

| 2006 | |

| 1352 | |

| 55 | |

| 3378 | |

| 237 |

Hispanics were recipients of every major U.S. military decoration during World War II; they have also been honored with military awards from other countries. Thirty-one Hispanic-Americans were awarded the

Hero Street, USA

In the Midwest town of Silvis, Illinois, the former Second Street is now known as Hero Street USA. The muddy block and a half long street was home to Mexican immigrants who worked for the Rock Island Railroad. The 22 families who lived on the street were a close-knit group. From this small street, 84 men served in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. The street contributed more men to military services in World War II and Korea than any other street of comparable size in the U.S. In total, eight men from Hero Street gave their lives during World War II—Joseph Gomez, Peter Macias, Johnny Muños, Tony Pompa, Frank Sandoval, Joseph "Joe" Sandoval, William "Willie" Sandoval, and Claro Solis. Second Street's name was changed to Hero Street in honor of these men and their families.[97]

Of the 22 families on Second Street, the two Sandoval families had a total of thirteen men who served in the

Eduvigis and Angelina Sandoval immigrated to the U.S. from Romita, Mexico. Their son, Frank, was a combat engineer assigned to help build the Ledo Road in Burma. He was killed when his unit was sent unexpectedly to the front to fight for control of a key airbase. His older brother, Joe, was assigned to the 41st Armored Infantry Division in Europe. He was killed in April 1945, just days before the war ended.[98]

Joseph and Carmen Sandoval also immigrated to the United States from Mexico. When the war broke out, their son Willie asked for permission to enlist in the army, and both parents consented to their son's request. Willie Sandoval was trained as a paratrooper and was assigned to the

Other families like the Sandovals had multiple members join the Armed Forces. The Banuelo family, originally from Mexico and who resided in

Home front

Some Hispanics in the entertainment business served in the United Service Organizations (USO), which provided entertainment to help troop morale. One notable USO entertainer was Desi Arnaz, the Cuban bandleader who starred opposite Lucille Ball in the television show I Love Lucy. When he was drafted into the army in 1943, he was classified for limited service because of a prior knee injury. As a result, he was assigned to direct the U.S.O. programs at a military hospital in the San Fernando Valley, California, where he served until 1945.[100][101]

Hispanic Americans who lived in the mainland benefited from the sudden economic boom as a result of the war, and the doors opened for many of the migrants who were searching for jobs.[102] After the war, many Puerto Ricans migrated to the United States to find work.[103]

Isabel Solis-Thomas and Elvia Solis were born in

Josephine Ledesma, from Austin, Texas, was 24 when the war broke out and worked as an airplane mechanic from 1942 to 1944. When her husband, Alfred, was drafted she decided to volunteer to work as an airplane mechanic. Even though the army waived her husband's duty, she was sent to train at Randolph Air Force Base, Texas, where she was the only Mexican-American woman on the base. After her training, she was sent to Bergstrom Air Field. There were two other women, both non-Hispanic, at Bergstrom Air Field, and several more in Big Spring, all working in the sheet metal department. At Big Spring, she was the only woman working in the hangar. She worked as a mechanic between from 1942 to 1944.[104]

Discrimination

In the military

During World War II, the United States Army was segregated,[107] and Hispanics were categorized as white.[3][108] Hispanics, including the Puerto Ricans who resided on the mainland, served alongside their "white" counterparts, while those who were "black" served in units mostly made up of African-Americans. The majority of the Puerto Ricans from the island served in Puerto Rico's segregated units, like the 65th Infantry and the Puerto Rico National Guard's 285th and 296th regiments.

Discrimination against Hispanics has been documented in several first-person accounts by Hispanic soldiers who fought in World War II. Private First Class Raul Rios Rodriguez, a Puerto Rican, said that one of his

After returning home

After returning home, Hispanic soldiers experienced the same discrimination felt by other Hispanic Americans. According to one former Hispanic soldier, "There was the same discrimination in Grand Falls (Texas), if not worse" than when he had departed. While Hispanics could work for $2 per day, whites could get jobs working in petroleum fields that earned $18 per day. In his town, signs read "No Mexicans, whites only", and only one restaurant would serve Hispanics.[113] The American GI Forum was started to ensure the rights of Hispanic World War II veterans.

Discrimination also extended to those killed during the war. In one notable case, the owner of a funeral parlor refused to allow the family of Private

Post-war commemoration

The memory of Hispanic American heroes has been honored in various ways: some of their names can be found on ships, in parks and inscribed on monuments. Captain

Latino organizations and writers documented the Hispanic experience in World War II, most notably the U.S. Latino & Latina World War II Oral History Project, launched by Professor Maggie Rivas-Rodriguez of the University of Texas.[118]

The failure of the

See also

- Hispanics and Latinos in the United States Marine Corps

- Hispanics and Latinos in the United States Navy

- Hispanics and Latinos in the United States Coast Guard

- Hispanics and Latinos in the American Civil War

- Hispanics and Latinos in the United States Air Force

References

- ^ "Hispanics in the United States Army". www.army.mil. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "WW II Veteran Statistics". The National WW II Museum | New Orleans. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ a b c World War II By The Numbers. Retrieved on August 22, 2007.

- ^ a b c Stetson Conn; Rose C. Engelman; Byron Fairchild (1961). "The Caribbean in Wartime". Guarding the United States and Its Outposts. U.S. Army in World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 4-2. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ a b c d e Bellafaire, Judith. The Contributions of Hispanic Servicewomen. Women In Military Service For America Memorial Foundation, Inc. Retrieved on July 10, 2007.

- KiB), Latino Leadership Link. Retrieved on August 24, 2007.

- ^ Hispanic Population of the United States Current Population Survey Definition and Background, United States Census Bureau, Population Division, Ethnic & Hispanic Statistics Branch. Retrieved on August 24, 2007.

- ^ CNN Latinos in America

- ^ Latinos who fought in Spain[dead link]. Retrieved on November 12, 2007.

- ^ "Bert Acosta". Aerofiles. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ Robinson, Richard. A. H., The Origins of Franco's Spain: The Right, the Republic and Revolution, 1931–1936 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1970) p. 28.

- ^ Lotz, Corinna, Battle for Spain: Review. A World to Win. Retrieved on November 12, 2007.

- ^ US citizens that fought against fascism. Retrieved on November 12, 2007.

- ^ "Memorial Complete Casualty List", USSWestVirginia.org, Retrieved May 21, 2008

- ^ "USS Arizona Memorial". National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- .

- ^ a b A Brief History of Aircraft Flight Simulation ( Flight Training ) Archived May 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Hispanic Americans – 1940s". Archived from the original on 2011-05-12. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- ^ History & Heritage. On the Battlefront: Latinos in America's Wars. Hispanic Online: Hispanic Heritage Plaza. Retrieved on August 4, 2007.

- ^ United States War Department, History of the 762nd Antiaircraft Artillery Gun Battalion; September 15, 1943, to May 31, 1945; Former designation 72d Coast Artillery Regiment; Fort Randolph, Canal Zone; Prepared at Inglewood, California and dated May 31, 1945; Available from the National Archives and Records Administration, Maryland.

- ^ United States War Department; History of the 891st Antiaircraft Artillery Gun Battalion; September 15, 1943, to February 28, 1945; Former designation First Battalion, 615th CA (AA). Fort Clayton, Canal Zone; Prepared at Inglewood, California and dated May 31, 1945; Available from the National Archives and Records Administration, Maryland.

- ^ "Military History". American Veteran's Committee for Puerto Rico Self-Determination. Archived from the original on 2007-07-04. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ Villahermosa, Gilberto (September 2000). "World War II". 'Honor and Fidelity' – The 65th Infantry Regiment in Korea 1950–1954 (Official Army Report on the 65th Infantry Regiment). United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ ISBN 0-89141-056-2.

- ^ Villahermosa, Gilberto (2000). "Juan Cesar Cordero-Davila". valerosos. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ "Martinez's DSC Citation". Archived from the original on 2016-06-08. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ^ "Who was Agustín Ramos Calero?" (PDF). The Puerto Rican Soldier. August 17, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2006. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ Hispanic contributions to America's defense. Retrieved on March 15, 2008.

- ^ NM Veterans' Memorial – History: World War II from a New Mexican Perspective Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on August 4, 2007.

- ^ History. bataanmarch.com. Retrieved on July 28, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Toledo Blade – Jun 9, 1980

- ^ Ralph Rodriguez was a witness to history in the Pacific; he survived Bataan's brutality to rebuild his life Archived 2009-07-09 at the Wayback Machine By Sara Kunz. Retrieved on August 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Vorenberg, Sue. Remembrance: Albuquerque WW II veteran Agapito Silva was Bataan Death March survivor. Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine The Albuquerque Tribune, June 19, 2007. Retrieved on July 25, 2007.

- University of Texas. Retrieved on July 25, 2007.

- ^ House Journals (PDF). State of Illinois. April 18, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ^ The 158th Regimental Combat Team (Bushmasters). Archived 2007-07-11 at the Wayback Machine Arizona Veterans Memorial, Inc. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ^ "1-158 Infantry Battalion". Arizona National Guard es. Archived from the original on 2007-05-26. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (1960-10-13). "'Hell to Eternity' Is Story of Marine Hero". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-07.

- ^ "Hispanic-Americans & The U.S. Coast Guard". Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved 2010-09-21.

- ^ Jose Robert Zaragoza; By D.J. Carwile Archived 2010-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 0828320292, 978-0828320290

- ^ History of the Tuskegee Airmen

- ^ Aces of the 78th. 78thfightergroup.com. Retrieved on June 27, 2007.

- ^ a b 1st. Lt. Oscar Perdomo. Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine Cavanaugh Flight Museum. Retrieved on August 5, 2007.

- ^ "Valencia, Eugene Anthony". History.navy.mil. Retrieved 2022-03-20.

- ^ Correll, John T. "The Nation's Hangar". Air Force Magazine. March 2004, Vol. 87, No. 3. Retrieved on August 4, 2007.

- ^ Captain Micheal Brezas. Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Hispanics in the Defense of the United States of America. Retrieved on June 27, 2007.

- ^ "Memories of a Jug Driver". worldwar2pilots.com. Archived from the original on 2007-05-17. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ El Mundo; "La carrera de Alberto A. Nido en las fuerzas aéreas de los EE. UU.; April 26, 1944; Number 9986.

- ^ Brigadier General Robert L. Cardenas Biography. United States Air Force. September 1, 1971. Retrieved on August 4, 2007.

- ^ Roll of Honor of the 314th Troop Carrier Group Archived March 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Flores, Santiago A. Richard Gomez Candelaria vs. Schulungslehrgang "Elbe" Archived 2001-08-16 at the Wayback Machine. World War II Ace Stories. Retrieved on July 4, 2009.

- ^ "Relatan hechos en que Participaron"; El Mundo; May 12, 1945; Number 10467

- ^ Muñiz Air National Guard Base

- ^ A Tribute to Hispanic Fighter Aces Archived May 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Navy's 'Fighting Two' Added to Greatness at Manila". Life. October 23, 1944.

- ^ "T/SGT. Clement Resto". valerosos.com. Archived from the original on 2007-03-25. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ William R. Hartigan Crew. Bell's Angels: 303rd Bomb Group. Retrieved on August 8, 2007.

- ^ Rhem, Kathleen (September 15, 2004). "Pentagon Hosts Salute to Hispanic World War II Veterans" (Press release). U.S. Department of Defense. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ McIntyre, Hannah. Women fill the gaps in the Workforce. Utopia: U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project, University of Texas. Retrieved on July 12, 2007. Archived September 19, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Experiencing War

- ^ "LAS WACS"-Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Seginda Guerra Mundial; by: Carmen Garcia Rosado; p. 60; 1ra. Edicion publicada en Octubre de 2006; 2da Edicion revisada 2007; Regitro tro Propiedad Intectual ELA (Government of Puerto Rico) #06-13P-)1A-399; Library of Congress TXY 1-312-685.

- ^ Treadwell, Mattie E. (1991) United States Army in World War II: Special Studies. The Women's Army Corps: The North African and Mediterranean Theaters. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 11-8. Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ^ "Chapter V: November 1942 January 1943: Plans for a Million Waacs".

- ^ Introduction: World War II (1941–1945). Archived February 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Hispanics in the Defense of America. Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ISBN 0-8359-0641-8

- ^ a b c Bellafaire, Judith. Puerto Rican Servicewomen in Defense of the Nation. Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Women In Military Service For America Memorial Foundation, Inc. Retrieved on June 20, 2007.

- ^ Falleció el Sargento Santandereano ELTIEMPO.COM

- ^ a b c Alexander, Joseph H. The Final Campaign: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa. The Senior Marine Commanders. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Retrieved on July 27, 2007. Archived May 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Elwood Richard Quesada: Lieutenant General, United States Air Force. Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved on July 10, 2007.

- ^ "Allen and His Men". Time. August 9, 1943. Archived from the original on April 14, 2001 – via 104infdiv.org.

- ^ Dorr, Robert F. (January 26, 2004). "Damn the Torpedoes! Former VCNO excelled in combat, technical roles". Navy Times. Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ Hispanic Heroes and Leaders From the Yester Years. Association of Naval Services Officers. February 27, 2007. Retrieved on August 8, 2007.

- ^ Griggs-Grundy News Archived 2007-10-08 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Military Locator & Reunion Service, Inc. Volume 2, Issue 4, December 2001. Retrieved on August 8, 2007.

- ^ Lippman, David H. "August 5, 1942 – August 8, 1942". World War II Plus 55. Archived from the original on 2006-06-14. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ^ Richard Worth; David Williams; Richard Leonard; Mark Horan. "Order of Battle: Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942". World War II – Battles Of The Pacific. NavWeaps. Retrieved 2007-04-15.

- ^ Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved on August 18, 2007.

- ^ Collection of the U.S. Military Academy Library, pp. 132–133; Publication: Assembly; Summer 1969 Archived February 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Patriots Under Fire: Japanese Americans in World War II". Archived from the original on 2007-11-19. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ Rentz, John M. "Bougainville and the Northern Solomons". Historical Branch, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^

Lodge, Major O.R., USMC (1954). "Appendix IV: Command and Staff List of Major Units". The Recapture of Guam. Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Retrieved 2007-12-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Appendix G Marine Task Organization and Command

- ^ "The Submarine Forces Diversity Trailblazer – Capt. Marion Frederick Ramirez de Arellano"; Summer 2007 Undersea Warfare; p. 313.

- ^ a b c USNA graduates of Hispanic descent for the Class of 1879–1959: Class of 1960–Present (Flag Rank). Association of Naval Services Officers. Retrieved on July 27, 2007.

- ISBN 0-06-097771-X. Retrieved on July 27, 2007.

- ^ Ruiz, Kenneth C. "The Luck of the Draw". motorbooks.com. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

- ^ The Medal's History. Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Retrieved on July 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Daniel Rothberg (2014-02-21). "Obama will award Medal of Honor to 24 overlooked Army veterans". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- ^ "Obama to Award Medal of Honor to 24 Army Veterans – ABC News". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Hispanic Medal of Honor Recipients. United States Army Center of Military History. October 3, 2003. Retrieved on 2007-08-05.

- ^ Williams, Rudi (June 28, 2000). "22 Asian Americans Inducted into Hall of Heroes" (Press release). American Forces Press Service. Archived from the original on March 1, 2010. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ a b c d e Medal of Honor Recipients: World War II (G-L). United States Army Center of Military History. July 16, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-08-05.

- ^ Silvestre S. Herrera. Archived 2007-08-12 at the Wayback Machine Home of Heroes. Retrieved on August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Medal of Honor Recipients: World War II (M-S). United States Army Center of Military History. July 16, 2007. Retrieved on August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Medal of Honor Recipients: World War II (T-Z). Archived December 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine United States Army Center of Military History. July 16, 2007. Retrieved on August 8, 2007.

- ^ a b Undaunted Courage Mexican American Patriots Of World War II (2005). Latino Advocates for Education, Inc.

- ^ Hispanics in Americas Defense: Hero Street U.S.A. Archived August 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine The Hero Street Monument Committee. Retrieved on July 27, 2007.

- ^ PBS-New York goes to War

- ^ Desi Arnaz Biography (1917–1986). Biography.com. Retrieved on August 5, 2007.

- ^ Desi Arnaz Biography. Archived 2011-05-22 at the Wayback Machine Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved on August 8, 2007.

- ^ Multiple Origins, Uncertain Destinies: Hispanics and the American Future (2006). Retrieved on September 13, 2007.

- ^ History

- ^ a b Rivera, Monica. A Woman ahead of her Time. Archived 2010-06-05 at the Wayback Machine Utopia: U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project. Retrieved on July 12, 2007.

- ^ Zukowski, Anna. Despite War's bleakness, Isabel Solis-Thomas, remembers a time of maturing, camaraderie and loyalty to U.S. soldiers. Archived 2009-07-08 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project. Retrieved on July 12, 2007.

- ^ Zukowski, Anna. Despite War's bleakness, Isabel Solis-Thomas, remembers a time of maturing, camaraderie and loyalty to U.S. soldiers. Archived 2009-07-08 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project. Retrieved on July 12, 2007.

- ^ A Chronology of African American Military Service from WW I through WW II. Retrieved on September 12, 2007. Archived July 21, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rochin, Refugio I. and Lionel Fernandez. U.S. Latino Patriots: From the American Revolution to Iraq 2003, An Overview. Julian Samora Research Institute – Michigan State University e-book series (2005). Retrieved on September 12, 2007.

- ^ Kerschen, D'Arcy. "Despite war's end and brother's horror stories, man was intent on joining military". U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project, University of Texas. Archived from the original on 2009-07-08. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ de la Cruz, Juan. "Man survived jungle fever, suicide attacks and kangaroos during service in Pacific". U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project, University of Texas. Archived from the original on 2009-07-08. Retrieved 2007-03-18.

- ^ Mathieson, Catherine. "Cuban immigrant found acceptance in Black Army battalion". U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project, University of Texas. Archived from the original on 2009-07-08. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ Green, Alyssa. "Alfonso Rodriguez figured that war was hell, but he never counted on having to fight bigotry as well as the enemy". U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project, University of Texas. Archived from the original on 2009-07-08. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ Farias, Claudia. Renaissance man of West Texas. Archived 2009-07-09 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project, University of Texas. Retrieved on July 28, 2007.

- ^ Felix Z. Longoria: Private, United States Army. Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved on June 27, 2007.

- ^ Holland, Dick (May 3, 2002). "The Johnson Treatment". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ Brown, Peter. "Hector Garcia Middle School: A school's design aspires to live up to its name". DesignShare.com. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ^ Remarks at a White House Ceremony To Unveil a Commemorative Stamp Honoring Hispanic Americans. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. October 31, 1984. Retrieved on May 12, 2007.

- ^ Narratives. Archived 2008-10-15 at the Wayback Machine Utopia: US Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project, University of Texas. Volume 4, Number 1 Spring 2003. Retrieved on July 12, 2007.

- ^ de Moraes, Lisa. Ken Burns and the Old Soldiers Who Wouldn't Fade Away. Washington Post, July 12, 2007. Retrieved on July 12, 2007.

Further reading

- 65th Infantry Division. Turner Publishing. 1997. ISBN 1-56311-118-7.

- Undaunted Courage: Mexican American Patriots of World War II. Latino Advocates for Education, Inc. 2005. OCLC 311622780.

- Arthur, Anthony (1987). Bushmasters: America's Jungle Warriors of World War II. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-01007-9.

- ASIN B0006COTKO.

- Esteves, General Luis Raúl (1955). ¡Los Soldados Son Así!. San Juan, Puerto Rico: Star Publishing Co. Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- Fernandez, Virgil (2006). Hispanic Military Heroes. VFJ Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9675876-1-5.

- Gordy, Bill (1945). Right to be Proud: History of the 65th Infantry Division's March across Germany. J. Wimmer. ASIN B0007J8K74.

- Hughes, Thomas Alexander (2002). Overlord: General Pete Quesada and the Triumph of Tactical Air Power in World War II. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-4783-2.

- ASIN B0007E631Y.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - Wilson, Marc (May 2009). Hero Street U.S.A.. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. OCLC 1162315694.

- Villahermosa, Gilberto N. (2009). Honor and Fidelity: The 65th Infantry in Korea, 1950–1953. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-116-1.

External links

- Official pages

- Hispanic Americans in the US Army at the United States Army

- Hispanic American in the US Army at the United States Army Center of Military History

- Hispanic American Medal of Honor Recipients at the United States Army Center of Military History

- Bellafaire, Judith A. The Women's Army Corps: A Commemoration of World War II Service", United States Army Center of Military History

- Pentagon Hosts Salute to Hispanic World War II Veterans, U.S. Department of Defense

- Academic Sources

- World War II By The Numbers", Education at the World War II Museum. The National World War II Museum. Retrieved on June 1, 2007.

- The Contributions of Hispanic Servicewomen

- Latinos and Latinas & WW II Oral History Project

- Other

- "Commands" – Puerto Rico's 65th Infantry Regiment

- "Puerto Rican Soldier" August 2005 publication

- Hero Street Monument